The United States should use a strategy of power, alliances, and triangulation to best navigate the emerging world of “great power” rivalries, Hoover scholar Victor Davis Hanson says.

The post-Cold War global order is in flux with the ascendency of an economically-driven China and its foreign policy of global hegemony, said Hanson in an interview.

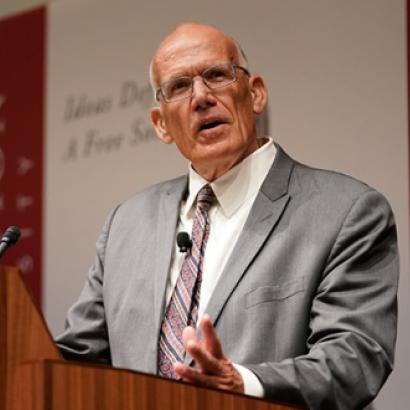

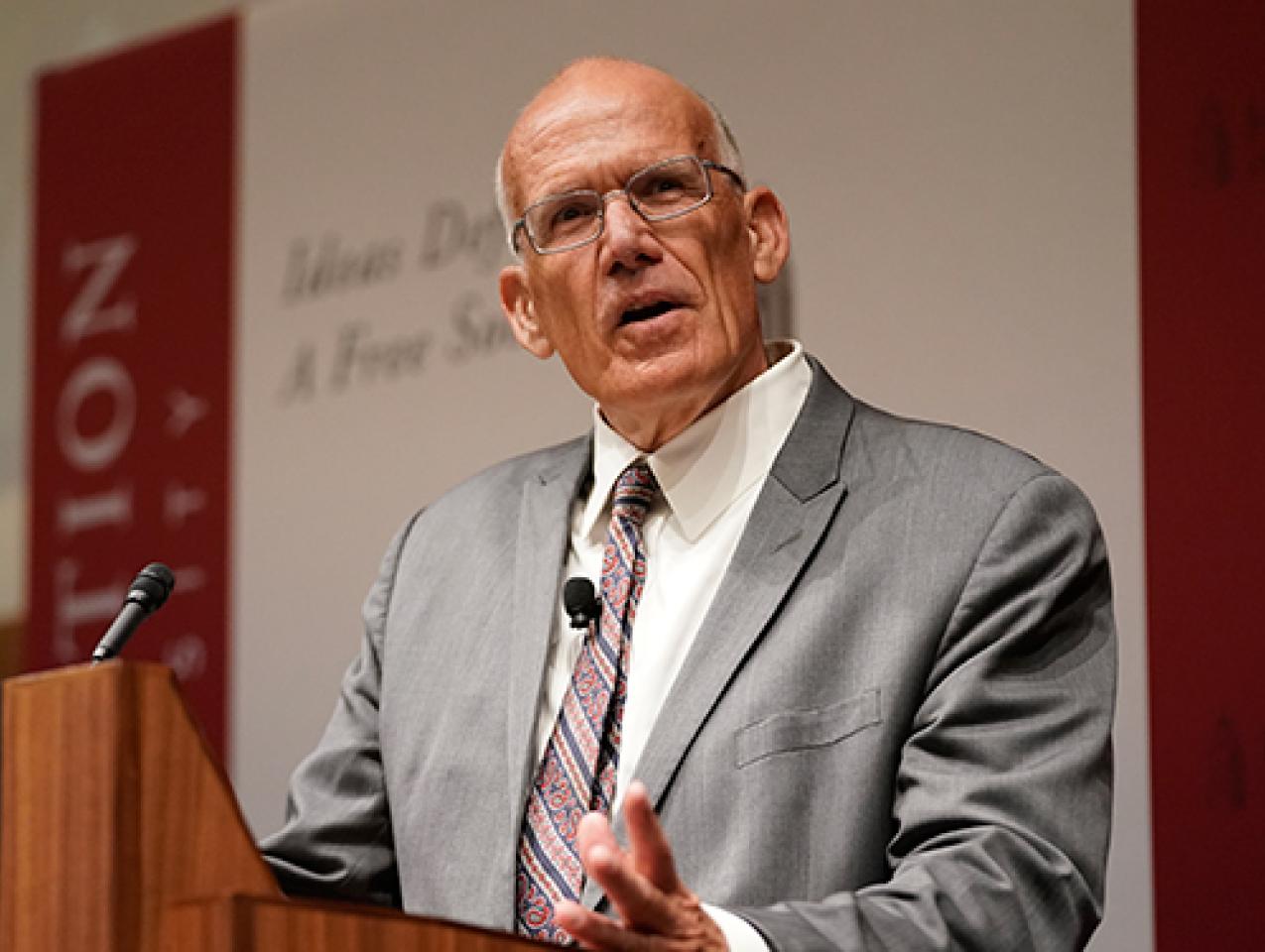

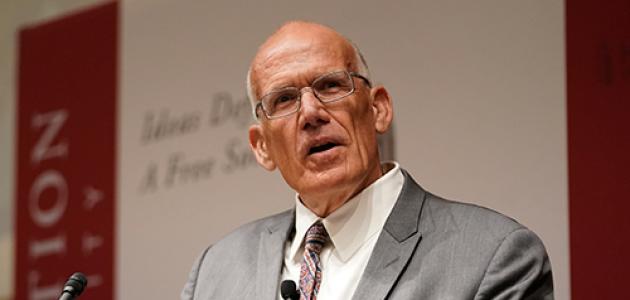

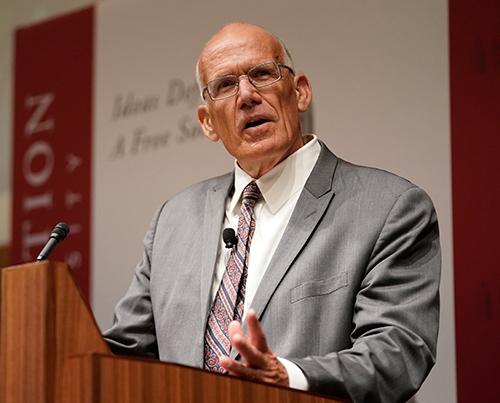

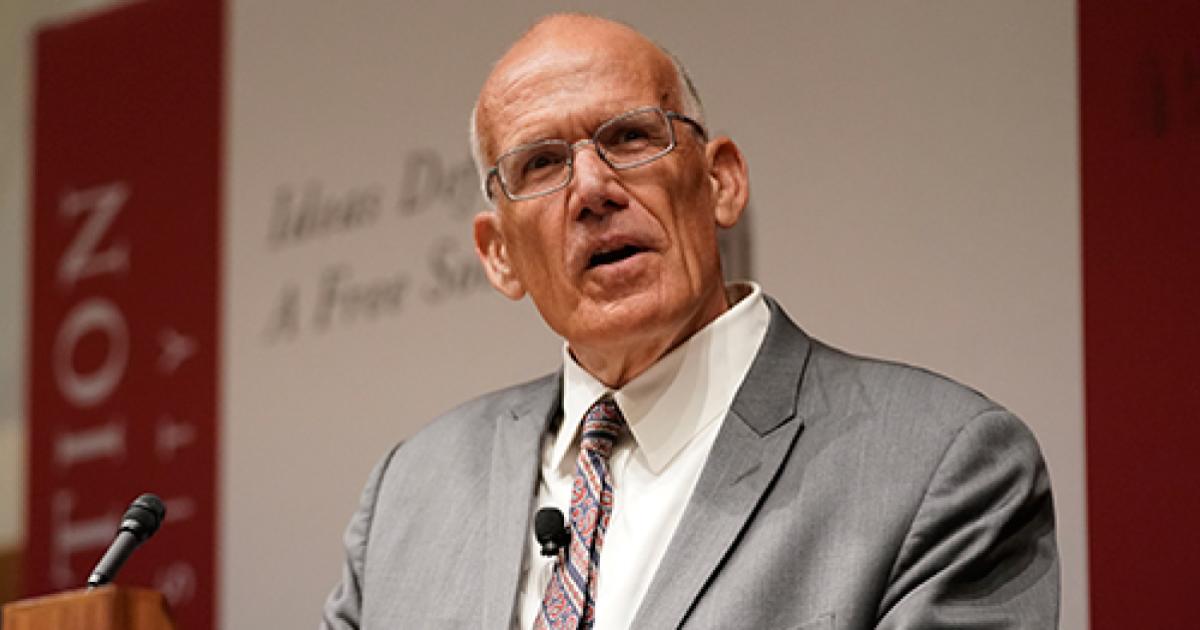

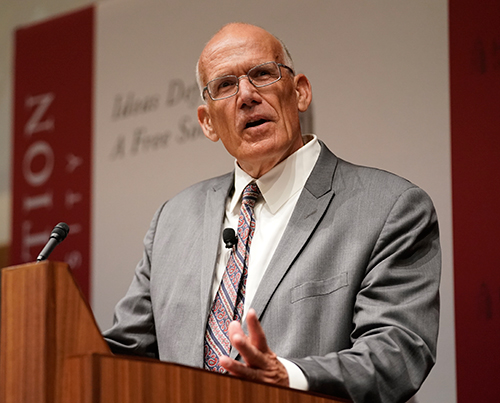

Hanson, the Martin and Illie Anderson Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, studies and writes about the classics and military history. He is the chair of the Hoover Institution’s Working Group on the Role of Military History in Contemporary Conflict, which met in early October to discuss whether the United States is entering a new great power landscape. A great power is a sovereign state that exerts influence on a global scale, whether through military, economic, diplomatic or so-called “soft” power methods.

“Calibrated and Planned”

Hanson describes China’s rise as “calibrated and planned” in the areas of economics and national security. As such, this puts the United States and the international system it led after World War II in the crosshairs of an increasingly assertive China, which now has the world’s second largest economy.

“There is no other real impediment to China’s envisioned role other than the US and its allies,” said Hanson.

Since 9/11, terrorism was widely considered America’s chief security concern, according to US policymakers; however, China has now eclipsed that threat on more fronts than one, he said.

“The limitations of rogue states and terrorist cabals are now apparent with the near destruction of ISIS in Syria and the growing isolation of Iran and its terrorist appendages. So, nation states have regained their prior importance over global terrorists. And globalization has given a number of states some sophisticated weaponry that gives them clout otherwise not earned by their own success,” Hanson said.

The ranks of non-American great powers, in descending order of importance, are China, Russia, the European Union, Japan, and India, he said.

“The US enjoys good relations with the latter three; not so much with the former two. Unfortunately for all the ballyhooed and enviable ‘soft power,’ Russia’s 6,500 nuclear weapons and China’s huge economy and population, and growing defense budget make them global players in a way the far more successful and humane societies of Europe and Japan, and India as well, do not,” he said.

Strategies, Alignments

The ancient methods of balance of power, alliances, and triangulation are the most effective means for the United States to deal with other great rival powers, Hanson said.

“For example, China and Russia should never consider either a closer friend than each does respectively the US. It is a pity that the hysteria over Russian collusion has prevented us from a realist use of Russia to balance at times China and vice versa. Poor decisions have brought the two closer together at our expense vis-á-vis North Korea, Iran, and the Middle East,” he added.

On other fronts, the United States should be aligning with Australia, Japan, the Philippines, South Korea, and Taiwan to deter Chinese aggression, and to ward off any idea that America’s allies will need nuclear weapons to protect themselves from China, Hanson said.

A number of classical distinctions mark “superpowers” in today’s terms, he said. This includes having a population over 300 million, the possession of nuclear weapons, an independent strategic air force, a blue-water navy, and an economy in the world’s top five or six. “By these inclusive calculations, we are the only superpower, but China is gaining fast,” he noted.

More Complexities, Less Existential

Hanson believes America is better off today because it is less likely that two rival superpowers (the United States and the former Soviet Union) would escalate conflict toward a nuclear war.

“That said, there are a number of rival regional powers with nuclear weapons—China, India, Pakistan, Russia, North Korea—that are not beholden to any superpower and have no restraint whatsoever on their choices of action,” he said.

Those countries have a number of border and other sorts of “sharp and ancient disagreements,” Hanson said.

While there are no existential Soviet-American fault lines involving 20,000 plus nuclear weapons and two antithetical belief systems, today more complexities and opportunities for devastating regional wars exist, he noted.

“China in some ways is a much less predictable and thus more dangerous rival than the old Soviet Union,” he said, “and is far more adaptable and powerful, given that its economy and population dwarf those of the Soviet Union, and its blueprint for global hegemony is multifaceted and not necessarily invested in a failed ideology.”

Western societies in recent decades made critical mistakes assuming “soft power” could deter aggressive states, Hanson said.

“I think we saw in the twenty-first century the shortcomings of a number of popular twentieth-century ideas from the hope that “soft power” was comparable to hard power (the EU economy and reputation cannot stop Putin from intervening where he wishes), that global wealth invariably leads to democratization and liberalization (it certainly did not in China), and that global institutions will replace the nation state (the United Nations and International Criminal Court lack both the power and morality of democratic nations),” he said.

Finally, Hanson noted America’s leaders erroneously believed that the United States could preemptively invade countries and remove dictators in order to stave off disasters and threats—and in the aftermath somehow miraculously “democratize the detritus of failed states.”

He said, “Afghanistan, Libya, Iraq, and Syria, despite occasional calm, do not seem they are ever going to look like Carmel or even Detroit or Chicago.”

MEDIA CONTACTS:

Clifton B. Parker, Hoover Institution: (650) 498-5204, cbparker@stanford.edu