This essay is based on the forthcoming book The Rise and Demise of Paper Money in Imperial China, 1000–1500: Fiscal Innovation, Market Growth, and Monetary Transitions by Richard von Glahn.

Over the past two decades, the issue of the “Great Divergence” in economic performance between Europe, where the Industrial Revolution occurred, and China, where it did not, has been a leading subject of debate and research among economics historians. One undisputed finding is that China achieved remarkable economic growth, by premodern standards, by relying on a different set of political and economic institutions from those that emerged in medieval and early modern Europe. A key feature of the Chinese economy was its distinctive monetary system, including the early development of fiat currency in the form of paper bills.

The invention of paper money in China preceded the first appearance of a viable paper currency in Europe—banknotes issued by the Bank of England in the early eighteenth century—by eight hundred years. Aside from technological factors—paper money required paper and printing techniques, both first invented in China—its precocious development there can be attributed to the unique features of Chinese money. The origins of coinage in China, as in the Mediterranean world, date back to the seventh century bce. But unlike the silver and gold currencies of the Greeks (and subsequently those of the Roman Empire and the European world), Chinese money took the form of low-value bronze currencies whose nominal value often diverged from their intrinsic metallic content. From the outset, then, Chinese money was fiduciary money whose value was based on trust. In addition, Chinese monetary philosophy diverged from the Western tradition. Whereas Western monetary theory focused on money as a means of market exchange and its role in setting “just” prices, in China money was chiefly conceptualized as a means by which the ruler could control markets and provide for the welfare of his subjects. These characteristics of the Chinese monetary system and monetary thought paved the way for recognizing fiat currency as legitimate money.

During the Song dynasty (960–1276), China experienced dramatic growth of the market economy, to the extent that historians speak of this era as China’s medieval economic revolution. Song mints reached the highest levels of output in Chinese imperial history, but the supply of bronze coins could not keep pace with market demand. In addition, the Song state transformed its fiscal base by relying primarily on money taxes derived from commerce and consumption rather than agricultural produce and labor services, further increasing the demand for money. Moreover, low-value base metal currencies were heavy and cumbersome to transport, making them ill suited for the purposes of long-distance trade.

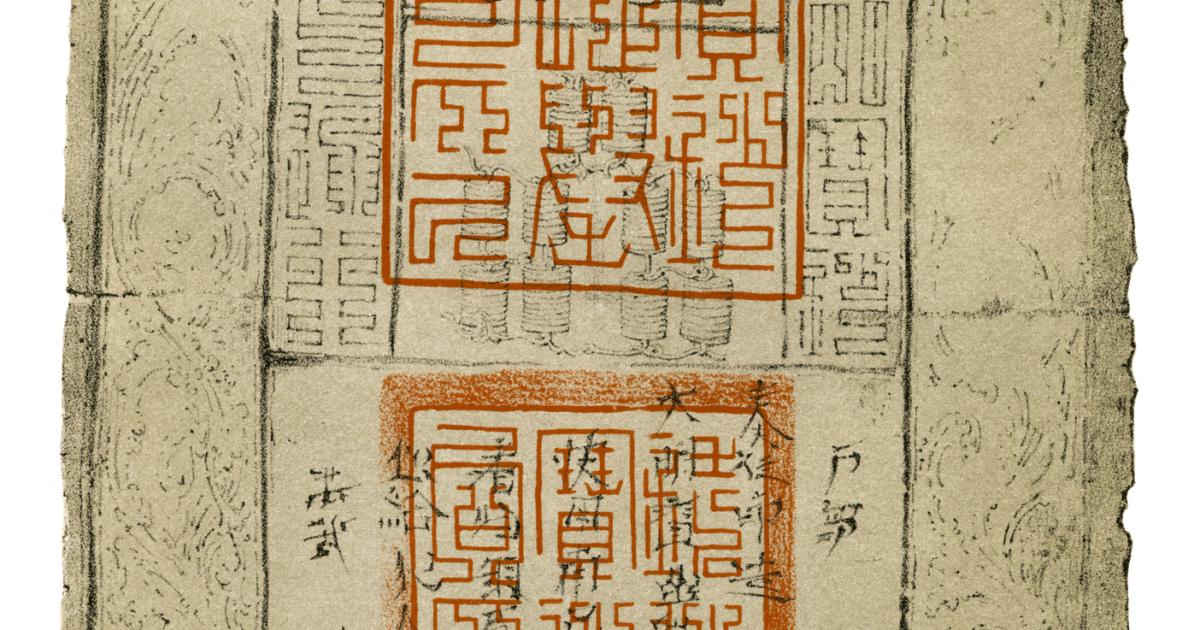

Paper money originated in the private sector. At the end of the tenth century, financial firms in Sichuan in western China began to issue paper money known as jiaozi in return for deposits of coin, silk, and other assets. But many of these firms engaged in speculative investments and fell insolvent, unable to redeem the bills they issued. After efforts to regulate private paper bills failed, in 1023 the Song government took over the issue of jiaozi as state-issued paper currency. Under government auspices jiaozi soon became the dominant money in the Sichuan region, largely displacing coin. In the twelfth century, under intense pressure to raise revenues for defense expenditures, the Song government introduced paper money to other regions of the empire, with considerable success.

The success of the Song paper currencies can be attributed to government policies designed to, in the words of contemporary policymakers, “maintain equilibrium” between different forms of money. Although paper bills were inconvertible with metallic monies, if the market value of its paper currency faltered, the Song state intervened to buy up excess bills using its reserve of silver bullion, thus restoring public confidence in their worth. Silver thus functioned as an implicit reserve currency. In addition, the state mandated the use of paper currency in tax payments; most money taxes were collected half in coin and half in paper money. Moreover, the state tightly controlled the amount of paper bills it issued and withdrew old and worn bills by requiring the public to redeem them every three years for new bills.

In the thirteenth century, threats of invasion by the steppe nomad kingdoms to the north (including, from 1234, the Mongol confederation) compelled the Song to issue exorbitant quantities of paper currency to pay for rising military costs. Although paper currency suffered severe depreciation, it became even more deeply entrenched in the private economy. By the time of the Mongol conquest of Song in 1276, paper money had become the monetary standard of the Chinese economy. The Mongol rulers of China not only continued the Song legacy of paper currency but went so far as to ban the use of bronze coins and silver in trade, relying solely on paper money.

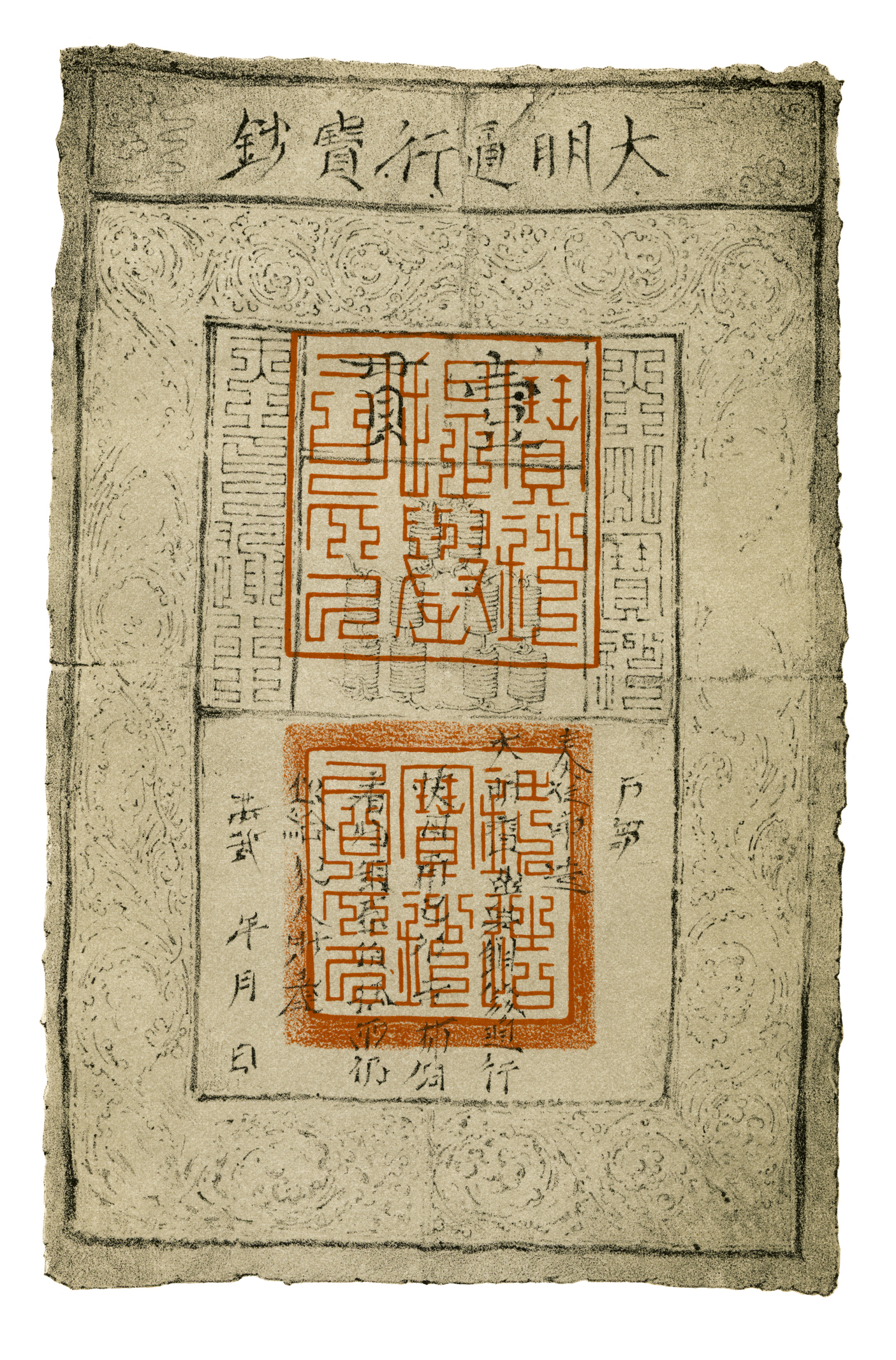

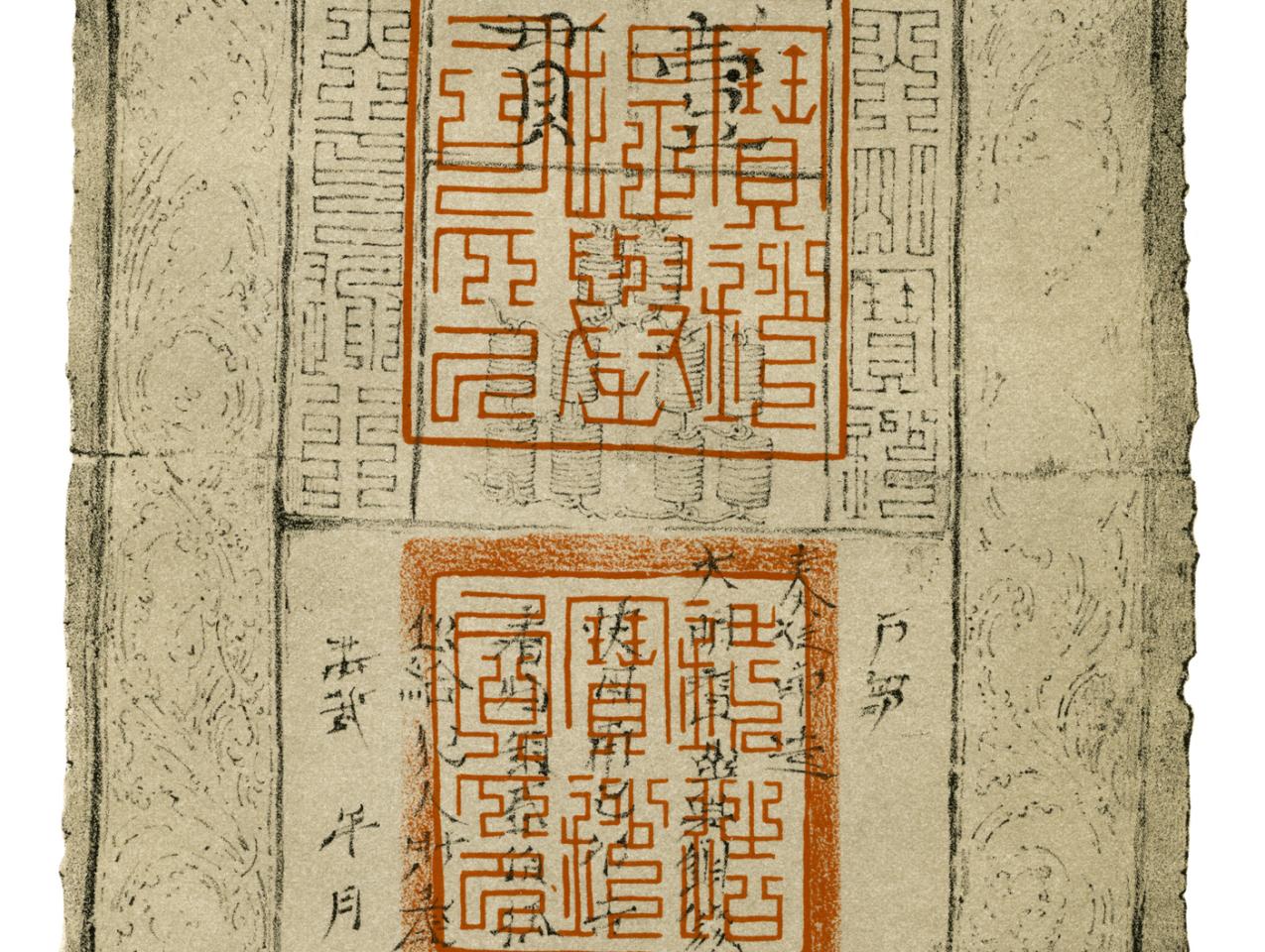

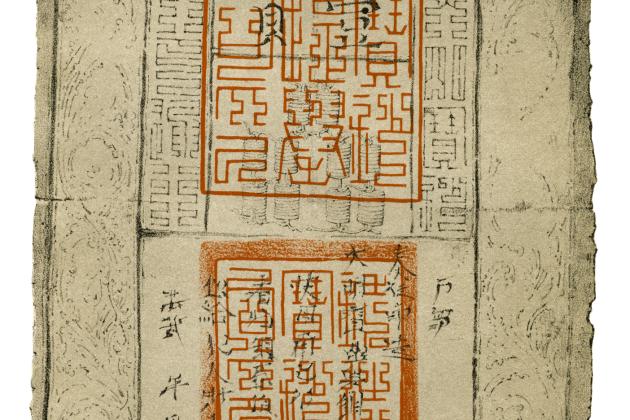

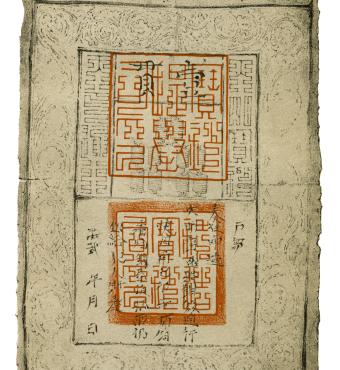

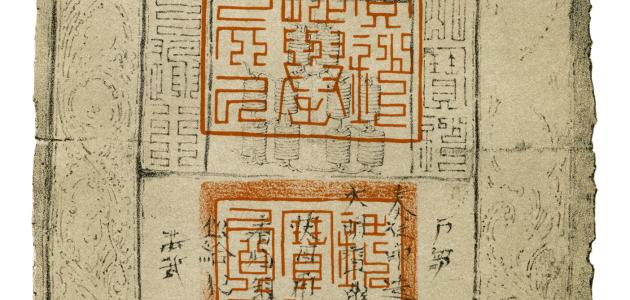

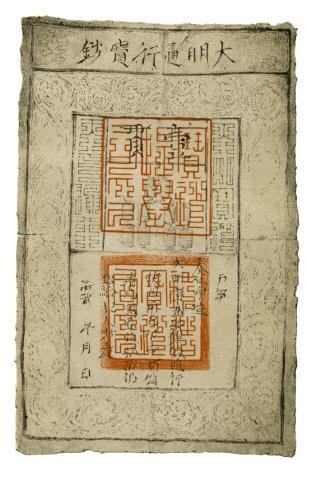

After displacing the Mongols, the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) likewise sought to institute its own paper currency. But fiscal mismanagement, notably the failure to collect taxes in paper money, caused severe depreciation, and by the early fifteenth century, Ming paper money was largely defunct. Subsequently the Chinese populace shifted to a bullion silver monetary standard in market trade and the Ming state too adopted silver as the basis of its fiscal accounts and taxation.

The rise and fall of paper currency in China between 1000 and 1500 attests to the unique features of the Chinese monetary system and monetary theory, the institutional innovations adopted by successive governments, and the crucial importance of fiscal discipline and sound managerial policies to “maintain equilibrium.” It also draws attention to the divergent institutional paths of economic development we witness across the premodern world.

Richard von Glahn is professor of history at UCLA.

This essay is part of the Long-Run Prosperity Research Brief Series. Research briefs highlight research that enhances our understanding of the factors that drive long-run economic growth and examine its policy implications.