- State & Local

- California

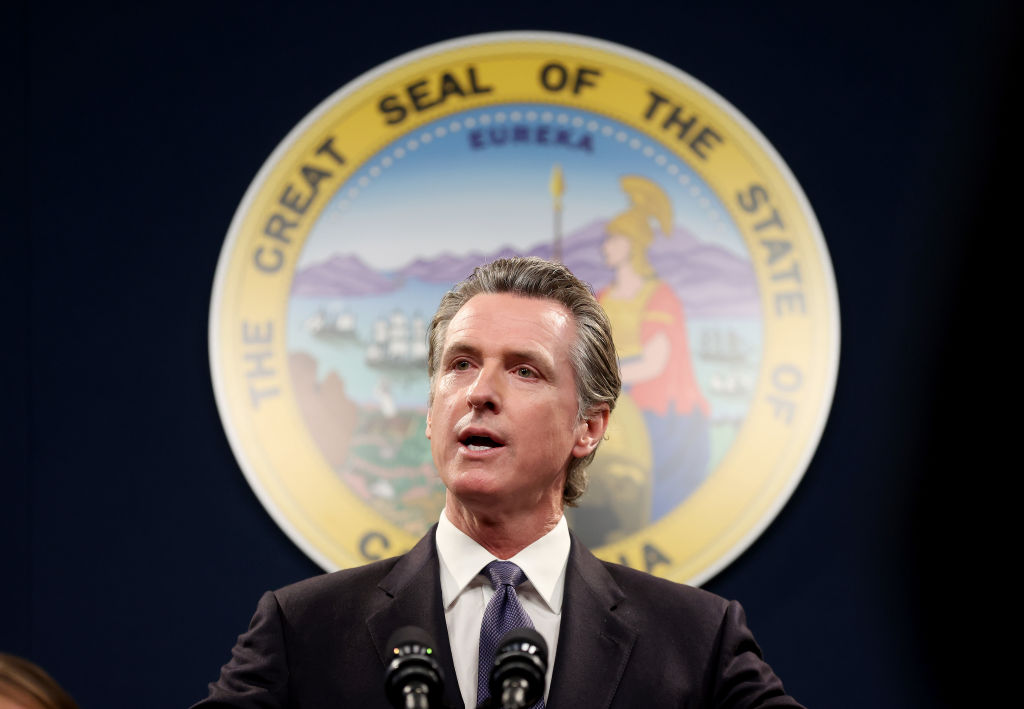

Let’s fast-forward to early January 2027 and the curtain coming down on Gavin Newsom’s run as California’s 40th governor. Newsom could use those closing days to tend to unfinished business— executive orders, appointments, and pardons.

Or, depending on what Mother Nature has planned, he could bring his eight years as California’s chief executive full circle by spending his last day in office the same way as his first: meeting with first responders in a high-risk fire area to talk about emergency preparedness (typical of what’s plagued Newsom’s governorship: big talk about better government tends toward terrible follow-up).

Yet another option—and this assumes Newsom is still as obsessed with presidential politics 16 months from now as he seems at present—he makes it a point to be seen in the company of Black voters.

Before we further speculate on what the future might hold for California, let’s look back at the last Democratic president’s last day in office.

For Joe Biden, that included a sentimental journey of sorts, a visit to a Black church in Charleston, South Carolina. Why that locale? Because, without the steadfast support of Black South Carolina voters in early 2020 (where they gave him a three-to-one advantage over Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders), Biden doesn’t win the state’s Democratic presidential primary and perhaps never winds up as America’s 46th president.

Indeed, Biden made that very point to congregants at North Charleston’s Royal Missionary Baptist Church—in doing so, singling out the South Carolina congressman whose support was pivotal in winning the primary: “I could not be standing here, I would not be standing here, and that’s not hyperbole, at this pulpit,” Biden declared, “if it were not for Jim Clyburn.”

Biden, ever the politician, went on to cite a list of deliverables for Black voters: choosing a woman of color as his running mate, appointing the first Black woman to serve on the Supreme Court, as well as the nation’s first Black defense secretary.

And, to show he wasn’t a stranger to such venues (Biden having claimed that he frequented Black churches as early as his teen years), the lame-duck president quoted a little scripture: “Your friends bear witness, they see your pain, they pick you up, they help you get to Sunday, from pain to purpose.”

So how does Biden’s last day in office relate to Newsom’s future?

First, let’s assume that South Carolina, as in 2024, is the first state to hold a Democratic presidential primary—that pole position very much in doubt as Democrats soon will decide their 2028 early lineup. (One possibility: a more competitive Southern state—Georgia or North Carolina—supplants South Carolina, which last went “blue” in a presidential election in 1976.)

Second, let’s assume that Newsom understands what worked for Biden in 2020: cornering the market on Black voters, who accounted for about five out of nine South Carolinians who participated in the Democratic presidential primary.

Third, let’s also assume Newsom appreciates Clyburn’s clout as a potential kingmaker. The good news for Newsom: Clyburn praised the governor, who stumped across South Carolina in early July (“I feel good about his [2028] chances,” said the congressman).

All of which leads to one question: What exactly would be Newsom’s appeal to Black voters?

Like Biden, Newsom can fall back on his political skills—knowing how to appeal to faith-based Black voters. In the South Carolina town of Florence, for example, Newsom recited calming words from the New Testament (referring to “many parts . . . but one body”—a Corinthians passage he got backwards) and the words of Martin Luther King Jr. (“an inescapable network of mutuality”) that turned out to have a short shelf life once July turned to August and calls for civility gave way to online Trump trolling.

And, like Biden, Newsom can point to judicial appointments—specifically, the two Black justices he’s named to the California Supreme Court.

But when it comes to policy and appealing to Black voters, Newsom faces some quandaries, including the following.

Poverty. Despite Newsom’s constant boasts about California’s financial majesty (such as its being the world’s fourth-largest economy), there’s a non-gilded underside to the Golden State existence—America’s second-highest unemployment rate, not to mention a housing market so brutal than one state lawmaker wants to make it legal for college students to sleep in their cars.

And there’s the disconnect of a California that’s simultaneously awash in dizzying wealth (the highest number of billionaires) and chronic poverty. According to the US Census Bureau, California leads the nation with a 18.9% poverty rate—with about 7.3 million Californians unable to make ends meet (more than all of the state of South Carolina, which had just under 5.4 million residents in 2023). In 2021, California’s poverty level stood at 11%.

Research by the Public Policy Institute of California paints a bleaker picture: in 2023, one-third of Californians “poor or near poor,” with 17.5% of Black Californians living in poverty. The best way to escape such impoverishment: get an education (PPIC claims that nearly 29% of Californians ages 25–64 and without a high school diploma lived in poverty versus only 7.6% of same-age college graduates). According to this Black Minds Matter report that examines disparities for Black students in California’s K–12 public school system, Black high school students in California have a dropout rate double that of White students; only three in 10 Black students met English language arts standards, and only 18% were proficient in math.

Altadena. The Southern California town that’s north of Pasadena and a short drive (in theory, at least) from downtown Los Angeles once embodied the California Dream of diversified neighborhoods and racial advancement.

Today, that same town is living a nightmare: an agonizingly slow rebuild in the aftermath of a natural disaster—one that’s been especially cruel toward Black Californians.

According to data compiled by several UCLA institutions, three-fifths of Black households in Altadena were located within the perimeter of January’s Eaton Fire versus 50% of non-Black households. Nearly half of those Black households were destroyed or sustained major damages—the same fates suffered by only 37% of non-Black households.

However, five months after the fires struck, only 15 building permits had been issued to Altadena homeowners—this in a town that lost more than 9,000 structures. But permitting is not the only problem (complicating matters is the fact that building codes have changed in the decades since some homes were constructed). There’s also the matter of insurance: an amalgam of homeowners either uninsured or underinsured, plus the state’s largest insurer lacking the funds to make good on claims.

Reparations. Among the Sacramento storylines that went overlooked while California’s political press corps obsessed over the governor’s anti-Trump tweet storm: the NACCP’s California chapter calling for the passage of two bills related to reparations for descendants of slavery. They are SB 437 (calling for the California State University system to establish a process for verifying genealogical eligibility for reparative claims); and SB 518 (establishing a Bureau for Descendants of American Slavery within California’s Department of Justice to oversee reparative justice efforts).

Meanwhile, there’s a more ambitious “Road to Repair” bill package put forth by earlier this year by the California Legislative Black Caucus. The bill’s 16 measures range from the politically benign (ACA 6 would prohibit slavery in all forms) to one that could dog candidate Newsom in more conservative corners of America (AB 7 would authorize priory university admissions for descendants of American slavery, in contrast to the voter-approved Proposition 209 and California’s current policy of nonpreferential admissions in public schools).

What’s not mentioned in “road to repair” package: “road” tolls.

Two years ago, economists told a state reparations panel that California could be looking at a $800 billion price tag (California’s current annual state budget totals $321 billion) were it to follow the recommendations of the California Reparations Task Force.

What has been offered so far: not so much money as an official mea culpa signed by Newsom (formal title: “California Apology for the Perpetration of Gross Human Rights Violations and Crimes Against Humanity, with special consideration for African Slaves and Their Descendants”).

The question for Newsom, as he enters his final year in Sacramento: At what point will the reparations conversation shift from the process to payouts?

Then again, maybe Newsom avoids that subject if his manifest political destiny still sends him to Washington, DC, albeit in a nonpresidential capacity,

Here’s how that might play out, with the added proviso that this scenario is about as likely as President Trump ending up in the Newsom-driven California Hall of Fame.

The scenario: Sen. Alex Padilla runs for governor, wins next November’s general election, and then names a successor to fill out the remainder of a term that expires in 2028. (Republican Pete Wilson faced the same scenario when he was elected governor in 1990, choosing a state senator as his replacement.)

Would Padilla dare to offer the job to Newsom—which might be an affront to party activists consumed by identity politics (California already having one White heterosexual male as a US senator)?

Would Newsom, in an act of reverse political migration (these days it’s senators leaving Washington to run for governor, not the other way around) take the job, knowing that it might close the door on a presidential run in 2028?

The answer to that second question—Newsom taking a road to Capitol Hill, not the White House—lies in another early primary state, New Hampshire, and its favorite poet, Robert Frost: the road not taken.