- Finance & Banking

- Economics

- Answering Challenges to Advanced Economies

- Revitalizing American Institutions

Jon Hartley and George Tavlas discuss George’s career as an economist, including as a central banker at the Bank of Greece, the history of monetarism (including George’s new book The Monetarists), Milton Friedman, and the evolution of central banking over the past decades, including its decline since the 1980s, and its renewed post-pandemic interest.

Recorded on August 29, 2025.

- This is The Capitalism of Freedom, the 21st Century podcast and official podcast with the Hoover Institution Economic Policy Working Group, where we talk about economics, markets, and public policy. I'm Jon Harley, your host Today my guest is George Tavlas, an alternate governor to of the Bank of Greece for the European Central Bank since 2008. He's also a distinguishing fellow at the WHO Institution at Safer University, and he was previously the Director General of the Bank of Greece from 2010 to 2013, and a member of the General Counsel and the Monetary Policy Council of the Bank of Greece from 2013 to 2020, who's also an advisor to the governors when the country entered the Eurozone and was involved in the management and resolution of the Greek debt crisis. Welcome, George.

- Thank you so much, Jon. It's a pleasure to be here, and I thank you for the invitation.

- Well, I, I wanna start by gaining into your early life. Where did you grow up and how did you first get interested in economics?

- I was born in Worcester, Massachusetts to Greek immigrant parents. My father left Greece and his village in Greece and his formal education when he was 12 years old, and he came to the United States at the end of the First World War. He worked his way up and became a successful business person. He owned several retail stores and rental properties. He learned to read and write in English and read the Wall Street Journal every day. Like many immigrants. He had a simple dream. He wanted to see his children have the education that he never was able to have. And so when I was 13, he enrolled me into the one of, one of the top prep schools in New England. It was located in, it is located in my hometown, it's called Worcester Academy. But then tragedy struck several weeks before I started my first classes. My dad died unexpectedly of a heart attack after that. I didn't take classes. I didn't take school seriously. And so my grades at Worcester Academy were terrible. I had to repeat my fir my junior year. And then I did something that perhaps was the first in the history of the school, which is pretty hard to do because the school was founded in the 1830s. I field my junior year a second time around. In fact, my grades the second time around were worse than the first time. Well, that summer, after the second junior year, a letter arrived at my home, addressed to my mother. It was from the headmaster of the school, and he advised her that the school board had determined that I wasn't college material. She should look elsewhere for me to enroll. My mother never saw the letter. I intercepted it and he immediately went to see the headmaster, and I asked him for another chance. He gave it to me. He allowed me to enter my senior year with the provision that my grades had to show immediate, immediate improvement. Well, that changed things around. For the first time, a fire was lit under me. I realized that I had to study. My grades went up. I applied to five colleges, was admitted into all of them. My family steered me to Babson College, be it's a business college because it had expected, it assumed that I was gonna go into the family business. And so the letter addressed to my mother some years later when I, on the day that I received my PhD degree, I showed my mother that letter for the first time at the same time that I showed her my PhD diploma. After I graduated from Worcester Academy, I attended Babson College, which is a, as I mentioned, a business school in, in Massachusetts at Babson. In my first year, I took an economic principles course with Bill Casey. Bill had just graduated from Boston College. We become lifelong friends. The course lit a fire. I knew from the, almost from the first that I wanted to pursue economics for a career. I liked the quantification and the logic of economics. The faculty at Babson encouraged me to do my graduate work at New York University. At NYU three courses were especially important for my future research. Monetary economics taught by Bill s, silver Bill and I have become lifelong friends. History of economic thought and econometrics. My dissertation combined the first two areas, monetary economics and a history of thought. Upon completing my PhD dissertation in 1977, I was offered a position as a macro econometric modeler and a newly formed economic analysis team at the State Department. The team was created by Richard Cooper Cooper, who had been teaching at Yale, and subsequently was the teacher at Harvard, had become under Secretary of State in the patter administration. He wanted to build

- Me very famous, very famous international comics who just passed away a few years ago.

- Excuse me. Yes, he did. Yes, he did. And he, yes, and he was an excellent economist and an excellent writer. Cooper wanted me, well, under the main motivation for the economic analysis team under, under Cooper was to create a group at the State Department that could support econ these state departments positions at interagency meetings. So while at at State, I learned how to build and simulate macro econometric models. While at state, I received an offer from the OECD in Paris to help them build their multi-country macro model. I accepted the offer and I took a leave of absence from the State Department in 1980. That turned out to be a good decision professionally and a great decision personally, because while living in Paris, I was able to visit Greece frequently because my mother had resettled there. And on one of those visits, I met my future wife, Sophia. After I returned to the State Department, George Schultz had become Secretary of State. Alan Wallace had become his undersecretary. Wallace had been his former colleague at Chicago, Martin Bailey, who had taught macro at Chicago in the 1970s, 1960s. In 1970s, he was a secret assistant secretary at the US Treasury had become the chief economist. Martin was a, the attrition, he was a brilliant, the attrition, he needed someone to do the estimation, to test his ideas, and I was the person to do it. We worked very closely together. We wrote several, published several papers that continued to re receive citations. I learned a lot from that from Martin. In 1985, I received an offer to join the IMF, and I accepted it at the IMFI was assigned to do research among other things on the international monetary system. One of the things I, I was especially involved with on was looking at the advantages and disadvantages of a country having an international currency such as the US dollar, a very topical, dis topical issue today in light of the tariffs. However, as I rose through the ranks at the IMF and was promoted to managerial positions, I had less and less time to do research, which I especially enjoyed. And so, having spent several years visiting the Bank of Greece in the late 1990s, I accepted an offer from the bank to become a director at the bank where I was able to continue to do research while at the same time continued to do policy relevant work in such areas as the Euro sovereign debt crisis, and of course, monetary policy. Among the, that I've had at the bank in 2002, the then governor appointed me as his then accompanying person, but it's essentially the same as his alternate on the governing council of the ECB. Now, the way this works, each governor at the ECB is allowed to bring one person with them into the meetings to be able to consult with the alternate takes the place of the governor should the governor not be able to attend the meetings. Since that appointment, success of governors at the Bank of Greece have reappointed me as their alternate on the governing council. So having served on the governing council as an alternate since 2002, continuously, I'm the longest serving member of the governing council. During the past 10 or 12 years, I've had the privilege to be visiting such institutions of Chicago on several occasions, Drexel Duke, and of course, the Hoover Institution at the invitation of John Taylor. These academic associations have been instrumental in, in helping me revisit the fierce debates over Milton Friedman's Monetarism in the 1970s when I was a graduate student. They become the, they became like a thread of my research over the years, and it's the reason that I was able to write the book, the Monetarists.

- That, that's terrific. I wanna talk about the mantras in a moment. I also just wanna talk about a little bit about your career. I mean, you're there at the dawn of, of, of the Euro. You, you've seen the, you know, the, the European debt crisis in the early 2010s play out. What do you think we've learned in the past 25 years since the advent of the Euro about the nature of monetary unions without a fiscal union? And and what do you think the Euro will look like in the future? I mean, do, do you see there being more fiscal integration in, in the future? Obviously there's a lot that's changing right now in Europe, in, in 2025 with Greece military spending and, and, and, and more debt being issued, for example, by Germany to, to partly fund this. But I'm just curious, having been there at the beginning, having seen some of its, and, and been part of managing some of its greatest challenges. Notably, you know, Greece, the SAR debt crisis in the early 2010s, and, and it's, you know, been put, put in a better trajectory. I mean, at the time there were a lot of questions around whether Greece would, would leave the Euro or other countries would leave the Euro. That that hasn't happened yet. But there are many critics, I guess you say that, that a a monetary union without a fiscal union is, isn't sustainable in the long run, and that encourages free riding on, on the part of some countries. I'm just curious what, what you've learned and, and what you think economists have learned about that, the nature of, of this monetary union.

- Well, I don't think that economists have learned a great deal about the need of a fiscal union. They ne they knew that before the Euro system started, they thought that the monetary con union could survive in the absence of a fiscal union, because they thought that the markets would, would impose discipline on countries that were spending extravagantly. But it didn't happen that way. Between 2005 and 2009, Greek government debt doubled from about a hundred external debt from about 150 billion to 300 billion. And yet, from much of that time, Greek interest rates were very low. The markets thought that if Greece got into trouble, the Euro area would bail increase. It wouldn't let a crisis happen. And so, while the Greek debt was building doubling, as I mentioned, in the five years, 2005 to 2009, especially during the early years, 2005 and six Greek interest rates were not ma very much different from German interest rates. So one lesson that, that we've learned from the Euro is that countries have to maintain their, their fiscal, fiscal host is in order. We've also learned that we need to have a stronger fiscal mechanism inherently in Europe, in case countries do get in trouble, where that mechanism can support the countries may perhaps impose policies on the countries to take should a crisis erupt. Now, when the crisis erupted in Greece in late 2009, the the Euro system had to rely on the IMF and the European Union. And it was a little bit unorthodox because having been at the IMF when the country got into trouble and the IMF visited the country to see what policies would be needed, the IMF would sit on one side of the table and the finance ministry and the central banks from the other country would sit on the other side When a Greek crisis erupted. We had the Bank of Greece and the finance ministry on one side. On the other side, we had the IMF, we had the European Commission, and we had the Central bank of the Euro area, the ECB. So in a way, there was an advi adv. There was a clash between our central bank, which was really the ECB and the policies that were being formulated to deal with the Greek crisis. In retrospect, the crisis that were taken in Greece were very, very contractionary. And it was very difficult for Greece to emerge from the crisis. We needed support from the rest of the union, but we didn't get the support. And so what happened, the markets of course, perceived this and they, they perceived that there's some other countries on the line that could possibly erupt into crisis such as Portugal, Ireland, and even Spain, which required a program for its baking system. So one lesson that we learned is that we need to have an internal mechanism within the Euro area. So we don't need to rely on the IMF. Sure. The crisis aup. Another thing that we learned was, and now as I mentioned at the beginning of the Euro area, people understood that we weren't a complete fiscal union. And that was going to create a problem. But one thing we didn't anticipate, nobody essentially anticipated maybe one or two people in peripheral journals. 'cause they came across one, one person who argued this in the early 1990s. But nobody paid attention to him. We learned that we needed a banking union. We need, we learned that if Greek banks got in trouble, the markets weren't going to believe that the Greek government, a small country, is going to able to take care of the banks. Now, we had a situation in the us I think it was in 2002, as Silicon Valley Bank got in trouble. You remember that. And one or two other banks followed Sue and those banks were going under, and it started looking like it could become a full scale crisis. And so the ma the stock market, the financial markets began to tank. And then one day within a, within of the crisis, having erupted Secretary of State, secretary of Treasury, Janet Yellen said all deposits will be covered in full the next day or around the same time. Jerome Powell said the same thing. Was it Jerome Powell who was, yeah, Jerome Powell said the same thing, we will bail out everybody. End of crisis. We did, we don't have that in the Euro zone. If the Greek government said in 2012 13, we'll take care of the Greek banks crisis over, where were they gonna get the resources? They didn't have it. So we also need a banking union. We also need a capital markets union to further integrate countries, you know, across countries. So there, there are certain, certain priorities or prerequisites for a well-functioning monetary union that we started to build. We're in the process of building, but we're not all the way there yet. We've learned lessons, we're applying it, but it's a slow lesson to come to a complete monetary union. And that's one reason why, despite the fact that the dollar has been under siege as an international currency over the last year, there's really no rival to come up in and take the dollar's place. It sh you know, it's Chinese wand. The financial markets are very opaque. Investors don't want to go with the Chinese, want the Euro area. We have tried to make the, the euro and international currency, but we still lack, the mechanisms are just underlined to make the Euro such a valid international currency. We're way away, some way away from doing that. We're working on it, it's moving in that direction. But things are slow. My governor, by the way, had had a, a guest column in the Economist about two months ago, John Y. Stone, which was pointed out all those issues in a very nice way.

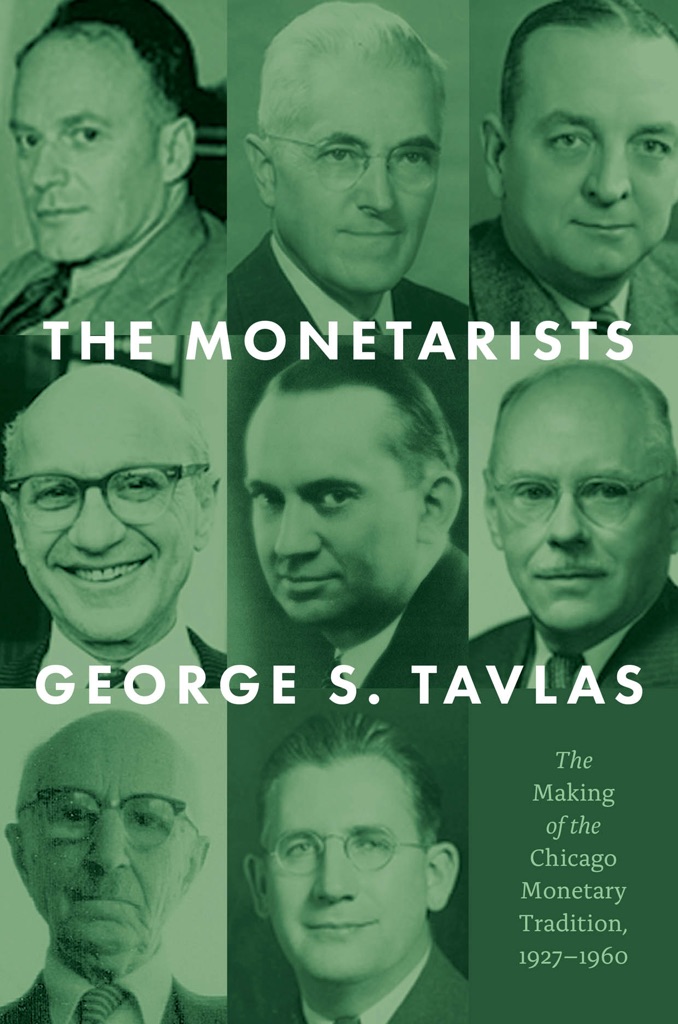

- Perfect. So I, I wanna get into your book, the Monarch First, which you published in 2023 with the University of Chicago Press. And this, this book essentially argues that on the topic of Monoism, which I think is, you know, broadly speaking, the, the doctrine that inflation is always in everywhere, a monetary phenomenon, and that mv equals pq. It's, you know, the quantity, the theory of exchange or the quantity theory of money that, that sort of front and center for, for monetary policy, that monetary policy aggregates matter. You know, some people, some monitors might argue or might we're certainly arguing in the 1980s that monetary aggregates were a tool, a monetary policy tool that should be used. I think c of should a bit away from that, obviously embracing interest rates. But this was an idea that was largely promoted by Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz in, I think the public Mind. You know, there was a, a big book that, that they released a monetary, a monetary history in the United States. Very famous book that that tries to make the case that the contraction of the money supply caused the Great Depression. And then this, this was published in, in the 1960s and a a, a very popular book and, and arguably one of Friedman's most influential books. Now, your book, the Monetarists sort of gets into this, you know, the intellectual history of Monetarism and argues that there was a tradition of monetarism before Milton Friedman in Anna Schwartz, largely at the University of Chicago. And I'm just curious, how, how did you get into, you know, the debates about Chicago Monetarism, and could you explain to us, you know, who some of these earlier Chicago interests were and, and how they might have influenced Friedman later?

- Well, how did I get into the debate?

- Yeah, I'm just curious, how, how did this, how did getting into this intellectual history begin for you and, and how did you sort of discover that, that the, the story of Chicago Monetarism begins well before Milton Friedman?

- Well, when I was doing my dissertation in the middle of 1970s, there was a heated controversy underway between Milton Friedman on one side and just about everybody else on the other side. Freeman had claimed that his moist views were the, well Friedman, let me backtrack. He had been a, a graduate student and a research assistant at the University of Chicago when the first had of, of the 1930s. And when Monetarism became, began traction in the, in the late 1950s and early 1960s, he had argued that his moist views derived from an, an important, what he called oral quantity theory tradition at Chicago. That tradition, he argued different from other versions, what he called rigid versions of the quantity theory utilized at other institutions because unlike those other versions, he argued that the Chicago version was policy relevant. And this policy relevancy argued was able to lead the Chicago quantity theorist less vulnerable to the Kenan Revolution and quantity theorists at other institutions. He singled out some of his mentors as having developed the Chicago quantity theory. I'll mention four of them. Henry Simons, Lloyd Minz, Frank Knight and Jacob Weiner. Now with the rise of Monetarism as a counter-revolutionary force in the late 1960s, Friedman's claim of a Chicago monetary tradition came under fire. The first to take game at Friedman was Dawn Patinkin, who had undertaken his graduate studies and undergraduate studies at Chicago in the 1930s and 1940s in 1969, writing in the inaugural issue of the Journal of Money Credit and Banking. Patinkin presented evidence, doctrinal evidence from the writings and teachings of his teachers at Chicago showing that Friedman's theoretical framework had nothing to do with what had been written about a taught at Chicago in the late 19, in the 1920s and 1930s. Because partic showed that the earlier Chicagoans used Irving fishers, as you mentioned, velocity based equation of exchange money times velocity equals prices times transactions. Whereas Friedman used a money demand approach to his monetary analysis. And so the issue arrived, arise that since the two theories were so different, how could they be related? Well enter into the picture Harry Johnson, who was Friedman Chicago colleague, not necessarily

- Famous international economist.

- No, huh. - A a very famous international economist. They

- Also, his Chicago colleague, not necessarily his Chicago friend, who used the occasion of the 1970 richer t Lee lecture in front of the American Economic Association to argue that, well, he made the argument that if in order to create a successful counter revolution to the Keynesian Revolution, Friedman had to establish some plausible linkage with Pres in Orthodox with what came before the Kings in revolution, Friedman solution and Johnson's words was to, and this is pretty brutal, to invent a Chicago monetary tradition and Johnson's words, Friedman had engaged in scholarly cannery and the debate with partaken on this issue in the journal political economy in 1972, Friedman admitted that his monetary theory had been influenced by Keynesian theory, but he also continued to insist that his overall monetary economics was, what he continued to argue was a direct outgrowth of a unique Chicago quantity theory tradition. He was incensed with both Patinkin and Johnson. He thought that Patinkin had mischaracterized the Chicago monetary tradition and by doing so, had damaged his treatments, professional reputation and private correspondence. He accused Johnson of having committed libel. And so while I was a graduate student, I had followed the debate closely and I decided to write my dissertation on the origins, the doctrinal historical origins of Monetarism. I wrote five essays, four had been accepted in journals. The fifth one dealt directly with the Freedman Patinkin Exchange in the Journal of Political Economy. I wrote a paper in which I showed that there were Chicago economists in the late twenties, early thirties, who were in favor of policy rules like Freeman. And not only that, they advocated a Freeman rule before Freedman did. They advocated that the money supply should grow by three to 5% annually.

- Hmm.

- I, I submitted that paper to the Journal of Political Economy. The editor wrote back that he, he sent the paper in his words to a learn scholar in the area. The Learn Scholar wrote a lengthy rejection letter. Now, at that time in the 1970s, one of the most popular graduate textbooks was Patinkin 1965. Money, interest in prices. I had studied it, read it many times, and studied it very hard. And I knew Patinkin writing style. I had no doubt that Patinkin was the guy who rejected my le my paper. So I then submitted the paper to the Journal of Money Credit and Banking. The editor wrote back that he sent the paper to an associate editor. The associate editor liked the paper, but he thought that the only two people that were really qualified to judge it with Don Patinkin and Milton Fried, the editor wrote, wrote to me that he asked Patinkin and Friedman to referee the paper. Patinkin wrote back that he already refereed and rejected the paper confirming my suspicion. Patin Friedman had not responded. The editor said, I leave it up to you to see if you can get Freeman to respond to your paper. I wrote to Freeman and told him what the circumstances were. He wrote a lengthy letter to the editor of the James CB telling him that the paper should be accepted. It was, it was published in 1977 and there began a lengthy correspondence between me and Friedman that lasted until a couple of months before Freedman passed away. That how is, that's how I got involved in the debate about the Chicago monetary tradition.

- That's fascinating. You know, all these characters were involved in, and you famously, a lot of these, you know, icon class economists would, would clash with each other. And I, I guess it's, you know, one thing that I guess some, some don't realize is that, you know, I guess the Chicago school isn't necessarily like a monolithic school of economists. And, and also, you know, it, it's, it is very fascinating that your pointing out this, this fact that, you know, the, the idea for like a K percent money growth rule sort of proceeded Freeman. I, I think, you know, the equation of exchange you mv equals pq goes back to I think David Hume maybe even earlier. So, you know, I, I think at some level there, there's sort of different, even different schools of monetarism in the sense that like, you know, today there, there's maybe some people who argue that I think increasingly following the early 2020s inflation, that which also saw the money supply or measures of money supply like M two grow pretty rapidly during that same time that we should look back to, to monetary aggregates, which previously had fallen out of favor. I guess my, my question,

- Can I just, lemme say one thing. Jon Monetarism is just not money. Money was the vehicle. The treatment thought was important for judging monetary policy, but the lasting contribution of Monetarism was to bring back or highlight the importance of monetary policy itself. In the 1940s, fifties, sixties, even the first half of the seventies, monetary policy was considered a secondary tool. It took a backseat to fiscal policy. What Freedman and Monetarism did, didn't bring back money. That was their way of saying that money was, that monetary policy was important, but what really mattered was monetary policy, whether with money or with interest rates. That monetary policy was one of the most important tools in the macro economy in the 1940s, fifties and sixties. It was downgraded, it had secondary status. So the Monetarist revolution, when some people say, well, where's money? It doesn't matter. What matters is, look where monetary policy is. It's right there on top. It's the, it's the primary tool for managing the macro economy. When mon, when the Federal Reserve or the European Central Bank make a decision on interest rates, everybody's following, everybody reacts. And depending upon the decisions, the reactions could be benign or they can be, they can be very volatile. But monetary policy is right there at the top of the policy list of the policy options that we have in the economy. And that absolutely is due to Monetarism.

- Absolutely. And it, it's worth noting that, you know, thinking back to the 1970s, I think, I think there, there was a, an idea that, you know, inflation, some people argued that, you know, price controls were the right answer to fighting inflation. You know, this was, I think, apparent in the Nixon administration,

- And that was Arthur Burns. That was Arthur Burns, who, when he was appointed chair of the, of the Federal Reserve, Friedman was ecstatic because he thought that Burns was somebody who understood monetary policy, but no burns relied, as you said, on price and wage controls. He let monetary policy run loose. And we had two episodes, one in the mid 1970s and one in the mid 1970s where inflation reached double digit levels. And it was Paul Volcker who came to on the scene, and he understood more as well as anybody else, the importance of endogenous expectations. He understood that markets had to re had to have fi have belief in that the Federal Reserve is doing the right thing. Volcker's approach was to apply cold Turkey, raise interest rates to close to 20%, let the economy go into recession. It had to prove something. It had to prove that the Federal Reserve was what we now call hard nosed. It had to credibility. The Fed gained credibility under Volcker and it maintained credibility under the success of Fed Shares like Alan Greenspan and Bernanke and Yellen. They all understood that credibility is very, very important. And when we had the rise of inflation in the early two twenties, both the ECB and the, and the Fed may have been a little slow react, especially the Fed, but the Fed had credibility, price expectations never took off because the markets had believed, believed that the Fed would take the necessary action to bring inflation back down. And it did. And that's all the legacy of the what happened in the late 1970s, early eighties from Volcker.

- You know, I also tend to think that there's two schools of of Monetarism and you know, I think there, there's various sub schools of monetarism in the sense that there's, I'd say a group of maybe passive monitors, think Milton Friedman K percent rule that argues, you know, that the Fed should just be run like a computer, just grow the money supplied by 2% every year. We don't need FOMC meetings or we don't need monetary policy council committee meetings, and that the central banks sole jobs should be just to ha you know, maintain price stability and do so with a constant money percent growth rule. And, and that's it. And I, I would say there's maybe another school of people who argue that, you know, yes, MV equals PQ matters, but you know, per Freeman's observation, you know, monetary policy is, is not neutral in the short run in that it can impact real economic variables and that the Fed or central banks should intervene during periods of recession, should provide monetary accommodation to improve real economic variables during recessionary times and, and should also contract the money supply when, when the economy's, you know, so-called overheating and you, you get big spurts of, of inflation. I'm curious how you've seen that play out, I guess in in your, in your research of, of the mantras of how people think, how different mantras have thought that money should be used in monetary policy.

- Well, I think Friedman wouldn't always say that a monetary role should be used all the time when we were in the Great Depression. He would, he would not have advocated a monetary rule. He thought that this was a time to employ activist monetary policy, expansionary monetary policy. What he does argue, however, is that by following a rule, we're less likely to have episodes as we did during a great Depression, that the, that the central banks sometimes do make mistakes. Sometimes they are under political pressures. We see that today, don't we? That they follow, that they make policy mistakes because it, because of the political pressures and for other reasons. And in order to keep the economy on a more even keel, you follow a policy rule. I think the same thing applies to a Taylor rule. The Taylor rule is, is an activist rule because it involves the economy responding to developments in the economy, whereas Friedman's rule does not, Friedman's rule is always three to 5% monetary growth. But the, a advantage of a monetary rule is that it prevents policy mistakes from occurring and it appre, it prevents political interference with monetary policy. The debate continues. It's hard to take a position on one side or the other, especially since I'm a central banker. And I don't want to, you know, I, I don't want to prejudge this issue as a central banker.

- I I wanna ask you about the current state of, of Monetarism and how, how it kind of fell out of favor in the sense that how monetarism in, in part has fallen out of favor at central banks and in monetary economics in, in, in academia. So, you know how I think of, I guess the sort of rough history of, of, of these things is you, you had the sort of old keynesians and then around the same time in the 1970s you sort of had both in, in the sixties and seventies, you, you had both monetarists emerging like Milton Friedman and those that were highlighting MV equals pq, which is I think very popular in the, the public, in in the public in general. MV equals PQ is I think a pretty easy thing to communicate. And then, you know, the, for a brief period of time, the Federal Reserve was targeting monetary policy aggregates in the 1980s. Then it sort of realized that money demand wasn't quite predictable and it kind of abandoned that. And then it moved toward targeting interest rates. So sort of in parallel what was going on at the same time in the seventies, you had the rise of the rational expectations revolution that influenced macro economists, you know, thinking, you know, Prescott sergeant and, and many others who were very influential. And, and the challenge there though was that, you know, policy monetary policy didn't really matter. So you also had folks, you know, the, the New King unions kind of emerged around that time as well. Folks like John Taylor, er, Alvo and, and and later Mike Woodford and, and Rich Claire and many others. George Galley who argued that, well if you have some sort of frictions, whether it's, you know, seeking prices or seeking wages or or seeking information that, that you could, monetary policy could produce real economic effects, you would get monetary, non neutrality. And, and, and not only that, but you also have interest rates as being sort of the key monetary policy instrument in, in that type of modeling. And so in the early nineties there was, I think this, you know, pretty quick shift along with when inflation targeting was introduced to sort of put interest rates as, as sort of the key policy instrument of, of interest, no longer money, no longer, you know, thinking about the money supply. And then we, you know, then central bankers got very focused on, on targeting inflation, 2% in particular largely to 2% inflation targets and use interest rates to, to achieve that and, and not necessarily target some sort of monetary aggregate growth. And, and I think we've kind of been in that regime for the past, say 35 years or so, where, you know, economists who are writing macroeconomic models write down these three equation DSGE models, you know, you came DSGE models and you know, there's, there's a Taylor rule in there, a monetary policy rule. There's a, a Phillips curve, there's an IS equation, or you think it was like an aggregate demand, kind of like a, a, a equation investment savings curve. And, and, and, and that's it. Money is nowhere to be found. So I'm, I'm just curious, there's some people who point to monetary aggregates as being sort of a useful indicator, maybe a predictor of inflation and, and many people on Wall Street, I think still use money and, and talk about monitors all the time. But largely when, when I hear about Tism today, it's not in academic seminars or from central banks, it's largely from Wall Street or the a few monetary congress and few mantras who are still out there. I'm curious, you know, what happened in your mind and is, is money making in any way?

- I I think you're gonna it pretty well, pretty right when you made the analysis about monetary aggregates were unstable in the 1980s and 1990s, and so central banks stopped putting an emphasis on, on growth of monetary aggregates. When the ECB started in 1999, it, its main pillar for monetary policy was M three growth with that lasted for about four or five or six years. And it, it became evident that focusing on monetary growth or monetary policy was not the right way to go, that the aggregates were unstable and could not be relied on. And so just like the other central banks, the ECB started focusing on interest rates. I think this is just taking into account reality now in the year two 20, when just before inflation started taking off, M three in the US jumped by, I think it was 35% in one year. We had a very, very large, perhaps not as large rise in M two in, in the Euro zone. And sure enough, a year or two later we had big surges of inflation. Now you can argue whether those surges were due to the, to the monetary growth itself, to the financing the fiscal deficits, especially in the US or to the supply side sharks that came from COVID in the Russian invasion of the Ukraine. But in any case, it, it provided some a, a bit of a rebound for the view that money is under monism matters. But it was just a, it was not a long lasting to make a long lasting impression on monetary policy makers. But what is important is what I came, what I referred to earlier is that, alright, we got inflation up as we did in 2223. How do we bring it down? We, we bring it down by wage price controls. Nobody ever talks about wage price controls anymore. We know they're a failure from the 1970s. We brought them down by high interest rates, monetary policy. If you didn't know the debates in the 1950s and 1960s, you would've never had suspected that monetary policy would become the chief instrument for dealing with shocks on the inflation front. So again, a lasting contribution from Milton Friedman was the emphasis that he put and other monetarists that they put on, on monetary policy per se, whether pursued through, by having the main instrument, the money supply or the main instrument, the interest rate. And don't forget when we had quantitative easing in, in the Eurozone in 2014, 2015, that was essentially increasing the money supply, try and get the interest rate up because we reached the lower bound of interest rates. We even had negative interest rates in the Eurozone, but they weren't being effective in bringing inflation up. So we relied on quantitative easing, which meant buying large purchases of, of bonds and increasing the money supply. So I would not go so far to say that monetarism as a emphasis on money is something that is no longer being discussed. It has been used, it has shown to be valid in the year 2020 years, 2020 and 21 in terms of bringing inflation up. And monetary policy itself has been the main tool for bringing inflation under control.

- Well, it's,

- And one other thing, let me let, if I, if I may, one of the tenets of monism or one of, yeah, I would call it a tenant of freedman's monism, was the importance of flexible exchange rates. When Friedman first wrote his article on the desirability of flexible exchange rates in 1953, he predicted the demise of the Bretton Woods adjustable PEG system. He said it couldn't last. He said we would move to a system of flexible exchange rates sooner or later we would get there. It was only system that would, that would be viable and sustainable. He was right in 1973, the world will move to a system of flexible exchange rates that became part of Monetarism. And so, you know, when we say monetarism, it's just not money, it's other things as well. It's rules versus discretion. It doesn't have to be a three to 5% monetary rule. You know, we now think that a Taylor rule works better, but it's rules versus discretion. So there are a number of aspects to Monetarism that have survived to this day, even though the emphasis on the quantity of money is not the, the main element that has survived.

- Absolutely. It's, it's interesting too. You know, you think about, I know we're talking about luxury advanced economies and times where I think inflation's been fairly stable. I think, you know, even if setting aside the early 2020s, you know, inflation jumping to nearly 10%,

- Over 10% in Europe,

- Over 10 in Europe, but in the US just under 10%. But you know, I think about, you know, all these episodes of hyperinflation and you the thinking to, you know, Zimbabwe thinking to Venezuela and thinking to all these episodes where, you know, there's been massive amounts of inflation. You can see, you know, there's obviously in all these cases there's a massive surge in the money supply and you know, there's Thomas Sergeant's very famous paper, the ends of of four big hyperinflations, I think is the, the title of it, the, the ends of four big Inflations. And it, this, that particular looks at all the interwar European countries, Germany, you know, why Germany, Austria, Hungary, that, that have these massive inflations, you know, they were trying to essentially inflate away their, their, their war related debts. And it's, it's interesting how just in all these cases, money is there and it's, it, it's, it's expanding enormously. And so, you know, all these regressions that I like to show of, you know, monetary policy growth versus inflation. When you plot all these, all this cross country data, you, you, you see a pretty clear relationship that you know, when, when you have massive inflations, there's always a a money story there. Now when we get into, you know, low inflation environments, like in advanced economies, you know, it, it's less clear that there's, you know, a a such a direct relationship between money and prices at, at, at lower levels of inflation. But a big, you know, with big hyperinflations money is al always growing enormously. So I think, you know, freedman's maxim that, you know, inflation is always in everywhere. Monetary phenomenon bears a lot of truth. I I think, you know, especially with larger inflations, especially with looking at the cross country and historical evidence. So I think, I think there's a, a very good, i I think monism itself for this idea that money is behind inflation, certainly I, I think holds up well, especially when we look at larger inflations. George, I, I really, I

- Wanna, and also it also holds up at five to 10% inflation rates too. There have been studies done that show that the money's a predominant cause of inflations in the levels between, as I mentioned, five and 10%. It's only at low low frequencies of inflation, one, two, 3%. That money is not, not an important variable these days, but at the medium frequencies and the very high frequencies that you mentioned, it's always a predominant cause of inflation.

- Absolutely.

- So one reason why perhaps less emphasis is in placed on money over the past 25, 30 years is because we've had low inflation rates, but as we know, we had a high inflation rate in 22, 23. And we also know that that was preceded by very high rates of money growth both in the US in the Euro zone.

- Absolutely. Well, well it's been a fascinating conversation George, really want to thank you for coming on and for all your excellent scholarly work on, on monetarism and monetary economics, so us all, your public service. It's a real honor to have you on.

- It's been a pleasure and an honor, and I thank you so much for having invited me.

- This is the Capitalism and Freedom of the 21st Century podcast, an official podcast of the Hoover Institution Economic Policy Working Group, where you talk about economics, markets, and public policy. I'm Jon Hartley, your host. Thanks so much for joining us.

ABOUT THE SPEAKERS:

George S. Tavlas has represented Greece at the Governing Council of the European Central Bank (as the Alternate to the Governor of the Bank of Greece) since 2008. He was the Director General of the Bank of Greece from 2010 to 2013, and was a Member of the General Council and the Monetary Policy Council of the Bank of Greece from 2014 to 2020. He participated in the management and resolution of the sovereign and banking crises in Greece. He was involved in the process of Greece's entry into the Eurozone as a key advisor to the Greek central bank's governors at the time. Tavlas was a member of the Supervisory Board of the Hellenic Corporation for Assets and Participations (HCAP), the sovereign wealth fund of the Greek government, from 2016 to 2019. In this role, he contributed to the design and implementation of the framework responsible for the privatization of state-owned enterprises in Greece as well as for the overall management of the large portfolio of state-owned assets in Greece.

Before joining the Bank of Greece, Tavlas was a Division Chief at the International Monetary Fund. He also worked as a senior economist at the U.S. Department of State, and as an advisor for the World Bank and the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development.

He has been Editor-in-Chief of Open Economies Review, (published by Springer) since 2005. He was a Visiting Professor at Leicester University, and a visiting scholar at the Brookings Institution, the Reserve Bank of South Africa, the LeBow School of Business at Drexel University, the Becker Friedman Institute at the University of Chicago, and Duke University’s Center for the History of Political Economy.

Tavlas is an active researcher in the areas of monetary policy, monetary doctrine, and time-series econometrics, with numerous academic publications. His book, The Monetarists: The Making of the Chicago Monetary Tradition, 1927–1960, was published by the University of Chicago Press in June 2023.

Jon Hartley is currently a Policy Fellow at the Hoover Institution, an economics PhD Candidate at Stanford University, a Research Fellow at the UT-Austin Civitas Institute, a Senior Fellow at the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity (FREOPP), a Senior Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, and an Affiliated Scholar at the Mercatus Center. Jon also is the host of the Capitalism and Freedom in the 21st Century Podcast, an official podcast of the Hoover Institution, a member of the Canadian Group of Economists, and the chair of the Economic Club of Miami.

Jon has previously worked at Goldman Sachs Asset Management as a Fixed Income Portfolio Construction and Risk Management Associate and as a Quantitative Investment Strategies Client Portfolio Management Senior Analyst and in various policy/governmental roles at the World Bank, IMF, Committee on Capital Markets Regulation, U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, and the Bank of Canada.

Jon has also been a regular economics contributor for National Review Online, Forbes and The Huffington Post and has contributed to The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, USA Today, Globe and Mail, National Post, and Toronto Star among other outlets. Jon has also appeared on CNBC, Fox Business, Fox News, Bloomberg, and NBC and was named to the 2017 Forbes 30 Under 30 Law & Policy list, the 2017 Wharton 40 Under 40 list and was previously a World Economic Forum Global Shaper.

ABOUT THE SERIES:

Each episode of Capitalism and Freedom in the 21st Century, a video podcast series and the official podcast of the Hoover Economic Policy Working Group, focuses on getting into the weeds of economics, finance, and public policy on important current topics through one-on-one interviews. Host Jon Hartley asks guests about their main ideas and contributions to academic research and policy. The podcast is titled after Milton Friedman‘s famous 1962 bestselling book Capitalism and Freedom, which after 60 years, remains prescient from its focus on various topics which are now at the forefront of economic debates, such as monetary policy and inflation, fiscal policy, occupational licensing, education vouchers, income share agreements, the distribution of income, and negative income taxes, among many other topics.

For more information, visit: capitalismandfreedom.substack.com/