By Jonathan Movroydis

Hoover Institution (Stanford, CA) – In August and September, Battlegrounds: International Perspectives on Crucial Challenges to Security and Prosperity, a Hoover video broadcast hosted by Fouad and Michelle Ajami Senior Fellow H. R. McMaster, featured interviews with three leading experts who analyzed the implications of the withdrawal of US troops from Afghanistan, the deteriorating security and humanitarian situation in that country, and the future of South Asia and the greater Middle East.

The United States Didn’t Have a Clear Plan for a Favorable Political Outcome in Afghanistan

On Wednesday, August 26, McMaster spoke with John Abizaid, a retired four-star Army general and former commander of US Central Command (2004–8). Most recently, Abizaid served as US ambassador to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (2019–21) during the Trump administration.

Abizaid argued that after September 11, 2001, American political leaders, seeking an immediate response to the perpetrators of the horrific attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, rushed into war without sufficient long-term planning. He explained that the war itself was based on the flawed assumptions that US forces would be greeted as liberators and that the political transformation of that country would be easy, because the Afghan people would readily embrace the principles of democracy and personal freedom.

Over a twenty-year period, however, the United States failed to consolidate military gains and achieve favorable political conditions. While the US helped the Afghans draft a new constitution and build democratic institutions, it failed to help root out corruption in the government and subdue sectarian tension, Abizaid maintained. These circumstances eroded public confidence in the Afghan government and empowered the Taliban to rebuild their forces and political support.

Abizaid asserted that the United States does not have to maintain an active troop presence across South Asia and the greater Middle East to combat and contain jihadist extremism. As an example, he relayed his experience in Saudi Arabia. He explained that while the kingdom’s leadership has had an historically abysmal human rights record, in recent years it has worked effectively with the United States to combat domestic extremism and should be regarded as a model to other countries in region.

Abizaid said that if the United States succumbs to pressure from political leaders at home who advocate the reduction of American presence in the Middle East, the US risks enabling major powers like China and Russia, and hostile regional forces like Iran, to fill the power vacuum, exacerbate sectarian violence, and destabilize the region.

“These problems with great power competition will only get worse with the diminishment of American power. To redeploy to the flanks of the world and leave the middle of the world vacant is a huge strategic flaw,” Abizaid said. “To abandon these ideological contests to the worst ideologies we can imagine, it is to give up what we have fought for ever since our country was born.”

Afghanistan Is Part of a Larger Terror Ecosystem

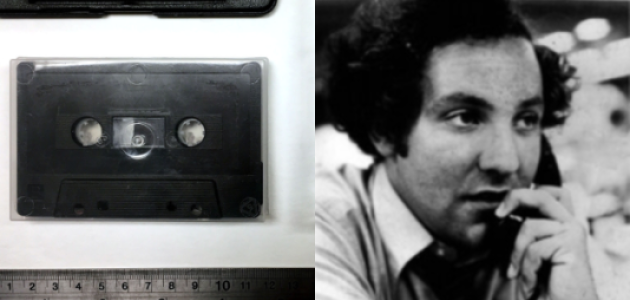

On Tuesday, September 7, McMaster was joined by award-winning journalist and author Peter Bergen for a conversation about his coverage of jihadist extremism over the past three decades, including his exclusive interview with Osama bin Laden in 1997 and his access to documents obtained from the compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan, where the al-Qaeda leader was killed by US Navy Seals in May 2010. The documents are the subject of Bergen’s recently released book, The Rise and Fall of Osama bin Laden (Simon and Schuster, 2021)

Bergen explained that American media and policy makers started to pay close attention to Afghanistan following the first World Trade Center attack in February 1993. Ramzi Yousef, the mastermind of the plot, had trained in Afghanistan. At the time, that country was experiencing a brutal war civil war that culminated in the assassination of its president, Mohammed Najibullah, and the installation of Taliban rule in 1996.

During this period, Bergen and his colleague Peter Arnette began investigating terror networks between Afghanistan and jihadist extremists in the Arab world. This trail ultimately led Bergen to interview Bin Laden in 1997, when the al-Qaeda leader first declared war on America and demanded US leaders withdraw their forces from the Middle East.

A year after the interview, al-Qaeda bombed the US Embassy in Tanzania, killing two hundred people, mostly that country’s natives. Bergen said that this event demonstrated that Bin Laden had no compunction about taking civilian casualties as part of a strategy to combat the United States. Bergen noted, however, that such actions would prove to be a mistake. Following the attacks of September 11, 2001, US forces invaded Afghanistan and killed and captured nearly all of al-Qaeda’s approximately two thousand fighters.

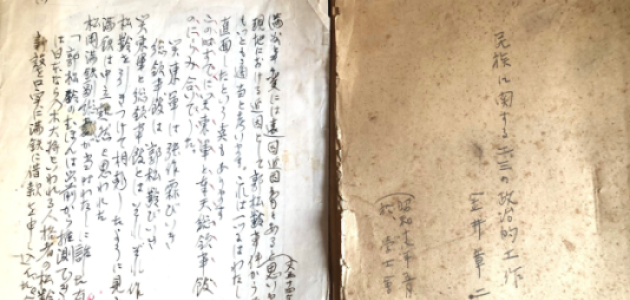

In the conversation, Bergen also discussed the documentary evidence captured at Bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad in May 2011. He explained that, in particular, diaries and other materials underline a terror ecosystem centered in Afghanistan and neighboring Pakistan. Nearly a decade after the attacks of September 11, 2001, al-Qaeda and the Taliban were still working in close collaboration. In May 2010, Bergen noted, al-Qaeda kidnapped an Afghan diplomat and demanded a ransom of $5 million. That money was later used to fund the Haqqani network, an Afghan insurgent group that is closely tied with the Taliban. That same month, al-Qaeda and Haqqani launched a terror attack at Bagram Air Force Base that killed an American contractor and wounded nine US troops.

“There is a lot of evidence in these documents about the close links between the Taliban and al-Qaeda,” Bergen explained.

Afghans Feel Betrayed

On Thursday, September 9, Yalda Hakim, an Australian journalist and Afghan native, talked to McMaster about her newly released BBC documentary, Return of the Taliban which captures the final days of US forces in Afghanistan, the frantic evacuation of Afghan citizens, and the Taliban’s eventual takeover of Kabul.

Hakim described how her documentary is rife with individual profiles that demonstrate that, contrary to assertions by the Biden administration, Afghans possess the indomitable will to fight the Taliban. She told McMaster that many Afghans, including one human rights activist she interviewed, had foreign visas and the ability to leave the country but decided to stay until the government’s fall was imminent, in hopes that they might be able to preserve their democracy.

She also explained that many Afghans felt betrayed about the Trump administration’s negotiations with the Taliban in Doha, Qatar, in 2020. Afghanistan’s political leadership didn’t have a seat at the table but nevertheless had an agreement imposed on them that included the release of Taliban fighters, who later fought and killed Afghan forces on the battlefield.

Hakim lamented that while nearly ten thousand Afghans were able to escape the reign of the Taliban, 38 million people, many of whom signed on and were committed to the democratic project sold to them by the United States two decades ago, were left behind.

“Even [American] presence in the airport in the last days gave some kind of hope to people that they felt safe,” said Hakim. “As soon as that last C-17 and soldier left . . . it suddenly just dawned on them that the lights have been turned out.”

Click here to watch Hakim’s BBC documentary, Return to the Taliban (Password: 0urw0rld!).

Stay tuned for future episodes of Battlegrounds.

Click here to watch The Fight to Defend the Free World, a PolicyEd video series in which McMaster addresses current US national security challenges.

Click here to buy McMaster’s recent bestselling book, Battlegrounds: The Fight to Defend the Free World (HarperCollins, 2020).