No country has been more aggressive toward its neighbors than communist China. In its seven decades of existence, the Beijing government has conducted more military actions against its neighbors than any other major country in the world—ranging from full-scale invasions, such as against India (1962) and Vietnam (1979, 1980s), to military actions of dangerous brinksmanship that nearly dragged the world to nuclear Armageddon, such as China’s bloody fights with the Soviet Union (1969) and its decades-long armed conflicts against U.S.-supported Taiwan (1954, 1958, 1995, 1996). One of the telling episodes that can inform the CCP’s peculiar way of war is the 1962 Sino-Indian war.

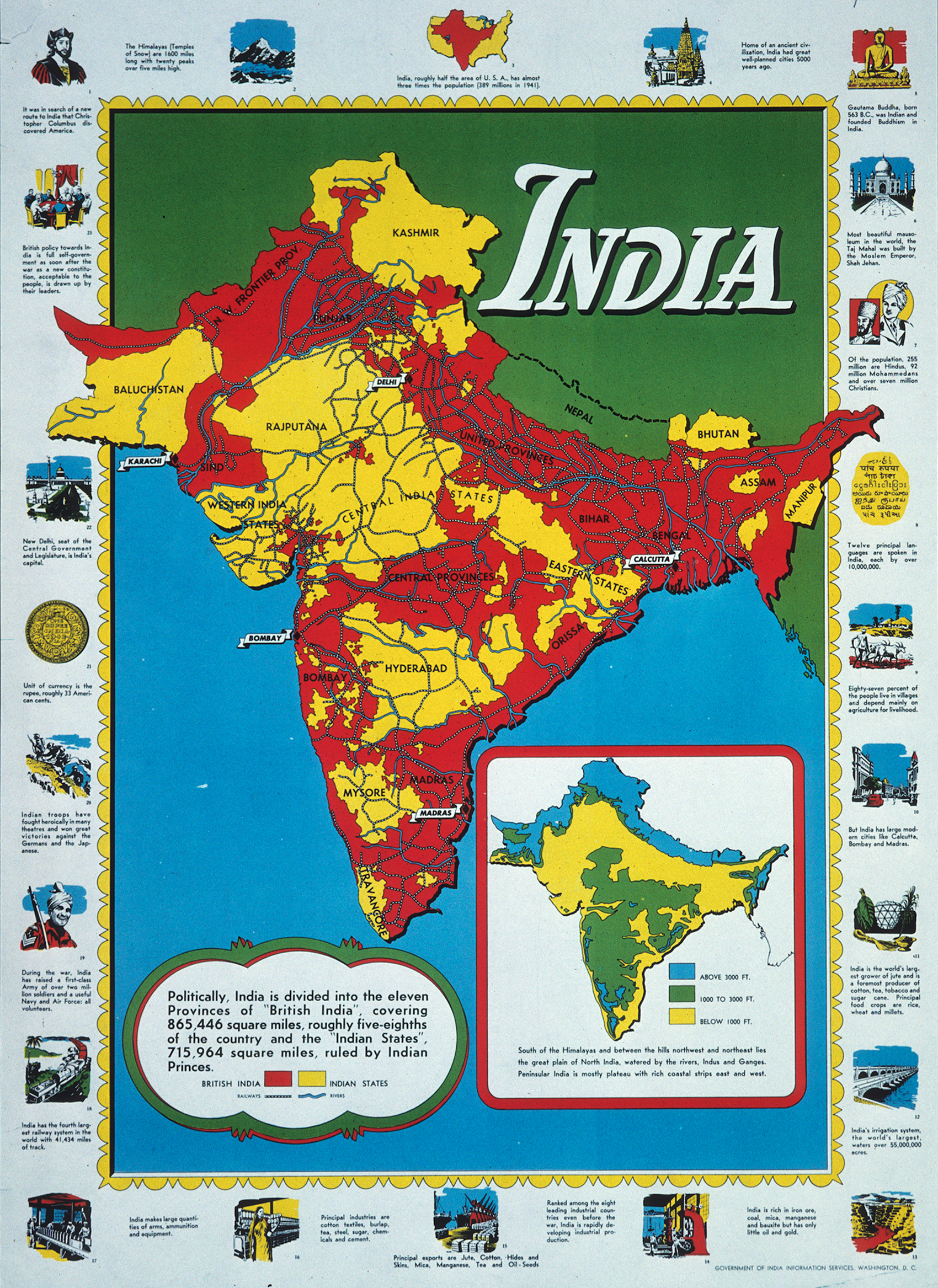

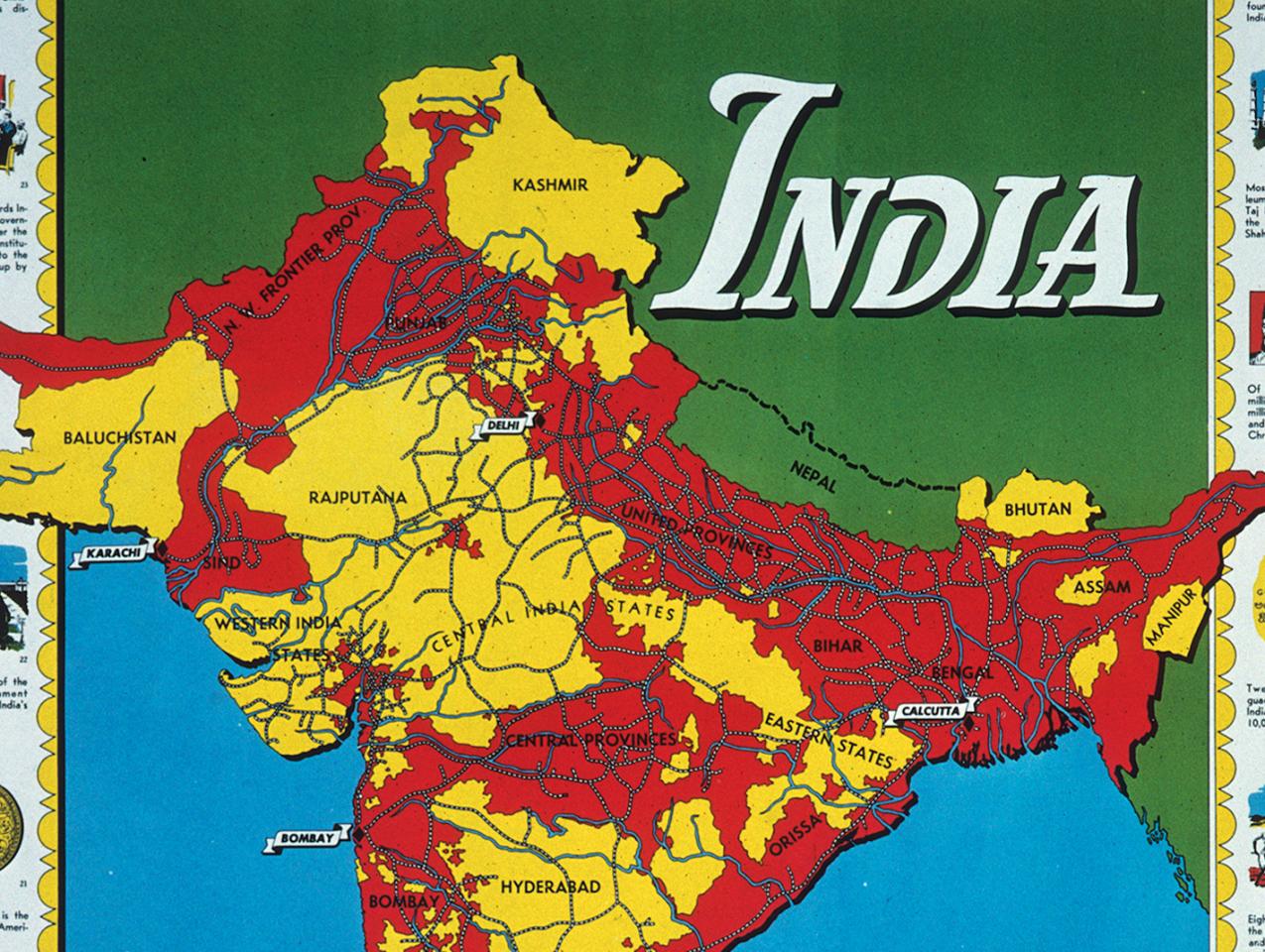

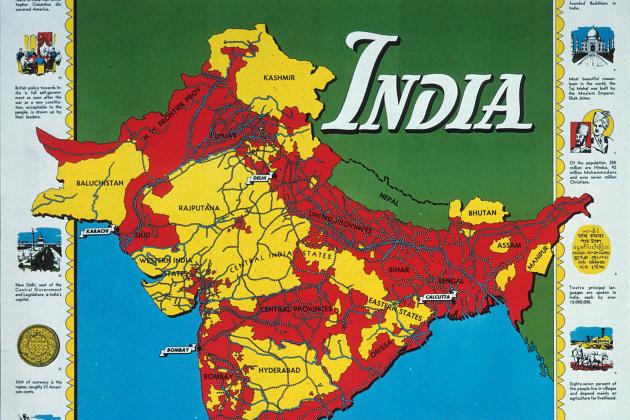

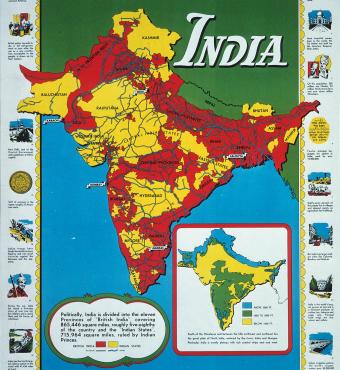

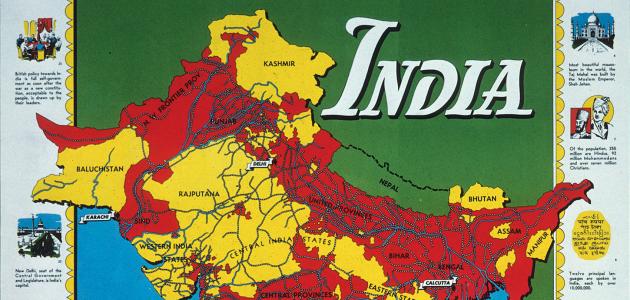

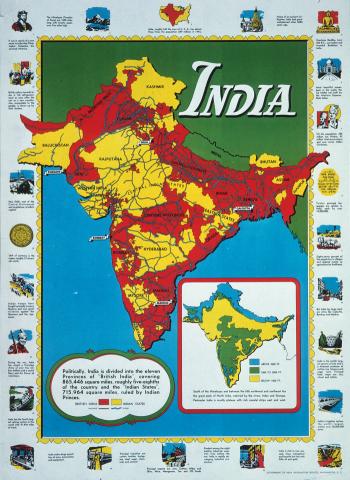

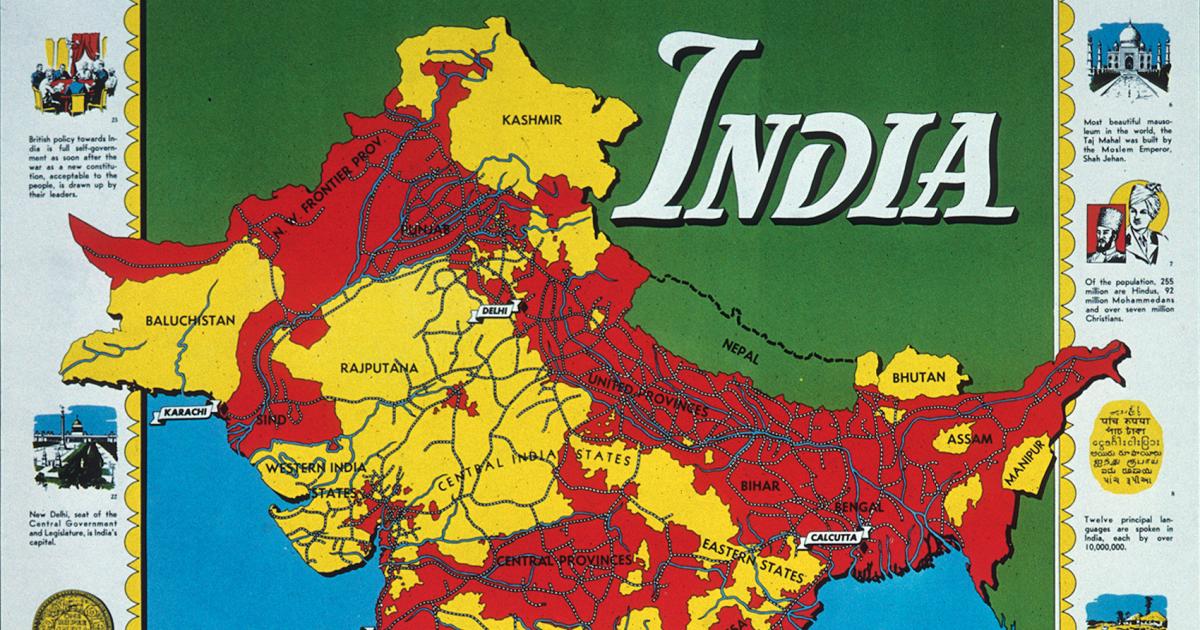

Between October 20 and November 21, 1962, China launched a full-scale war against India along the long borders between Asia’s two largest countries. Outnumbering the unprepared and poorly equipped Indians by four to one, more than 80,000 Chinese PLA troops fought the Indians in two main theaters more than 600 miles apart: Akai Chin and the North-East Frontier Agency (or NEFA, part of today’s Arunachal Pradesh, roughly what the PRC calls South Tibet). The war ended with China’s victory, with the PRC consolidating its control in Akai Chin. Yet the pre-war Indian-Chinese border demarcation in the NEFA remained largely unchanged.

But the PRC does not wage wars and conduct military operations with reckless abandon. The CCP leadership is calculative, methodic, and extraordinarily opportunistic in choosing the timing, scale, and intensity of its military moves.

Remarkably, how the war with India started, proceeded, and ended was critically determined by the most dramatic episode of the Cold War, the Cuban Missile Crisis, which the CCP viewed as the ultimate litmus test of the Soviet Union’s devotion to combatting imperialism by Western powers. In fact, China launched the full-scale war against India when the Cuban Missile Crisis started and ended it one day after the Caribbean crisis was effectively over.

China’s road to war with India was a long and torturous one. For the first decade of communist rule in Beijing, China got along fairly well with India, without any major border tensions. But the border issue suddenly flared up after Indian Prime Minister Nehru provided a refuge for the fleeing Dalai Lama in 1959 after Chinese communists crushed an uprising in Tibet.

The larger context of the Sino-Indian War, however, was the internecine Beijing-Moscow fight for leadership of the world communist movement. By 1962, Nikita Khrushchev’s Soviet Communist Party and Mao Zedong’s Chinese Communist Party had completed a bitter ideological split, primarily over the issue of whether the world communist movement in a nuclear era should co-exist and peacefully compete with the U.S.-led capitalist world. To Mao, with the Soviet Union’s advancement in nuclear and missile weapons, global power balance had tilted considerably in communists’ favor, and so the Soviet Union should lead a final armed showdown with the U.S.-led West, indeed a great leap forward in the global strategic struggle against the United States and its allies.

Khrushchev’s desire to sit down with President Eisenhower to manage a three-pronged relationship with the U.S. to avoid a mutually destructive nuclear war—peaceful co-existence, peaceful competition, and peaceful transition—was therefore viewed by Mao as treacherous “Soviet Communist Revisionism” and “Rightist Capitulationism.”

Shocked by Mao’s reckless bravado, Moscow responded to Mao’s warmongering with a sudden withdrawal of its massive military assistance to the PRC: it recalled thousands of Soviet weapons experts from China’s defense industry, and began to cultivate friendly relationships with China’s many neighbors fearful of the CCP’s aggressive territorial demands––especially India, with whom Khrushchev shared common views on the Sino-Indian border dispute, and signed an agreement in 1961 to supply the Indians with the advanced MiG-21 jet fighters to deter China.

But the anticipated Cuban missile crisis united Comrades Khrushchev and Mao. To Beijing, Moscow finally had the courage to play nuclear brinksmanship with the United States in its backyard. To Moscow, Beijing’s backing the Soviet Union over nuclear missile deployment in Cuba could regain its credibility in the world communist movement, and Khrushchev was willing to betray its erstwhile partnership with India to get China’s backing over Cuba.

The horse-trading between Moscow and Beijing at the expense of India was deliberate and intense. In the months leading to the Sino-Indian War, the Soviet ambassador to India, Ivan Benediktov, and chargé d’affaires, I. Cherkasov, repeatedly held conversations in New Delhi with their Chinese counterparts Pan Zili and Ye Chengchang, a rare move when Moscow and Beijing had virtually no normal diplomatic contact overseas of any sort. On October 13, one week before China launched the pre-emptive war against India, Khrushchev in Moscow summoned Liu Xiao, the Chinese Ambassador to the Soviet Union, and told him in unambiguous terms that Moscow supported Beijing’s protests against India’s territorial encroachment. The next day, Khrushchev led the entire Soviet Presidium to give Liu Xiao, the only official channel in Moscow available to Mao at the time, a lavish banquet in which the USSR’s intention not to back India in the pending border war was further made clear.

Moscow’s perfidy was public too. The day Chinese troops poured into India, Khrushchev urged Nehru to settle the dispute with the Chinese peacefully. Five days after the war started, Pravda published verbatim Beijing’s high-pitched press release on the Sino-Indian War, thus unambiguously reversing its prior support to India over the border issue, and openly endorsing Beijing in the dispute.

But Moscow had already agreed to a supersonic fighter/interceptor MiG-21 export transfer deal with India in 1961. Khrushchev did not feel strongly about breaking the agreement either. Nearly three weeks before the outbreak of the war, PRC Premier Zhou Enlai took the unusual step of seeking out the Soviets for talks and briefed the Soviet ambassador to China, Stepan Chervonenko, on India’s troops movement along the Chinese border and asked about Moscow’s MiG-21 agreement with India. Khrushchev immediately told Liu Xiao that Moscow would delay the MiG-21 program with India. Reciprocating all these moves from Moscow at the height of CPSU-CCP ideological fight, Beijing took the unusual step of informing Moscow of the outbreak of the war with India, to which Khrushchev responded with an immediate suspension of the MiG-21 transfer deal with India.

The Soviets clearly hoped for reciprocity from Beijing on supporting Moscow in the Cuban Missile Crisis with the United States. Starting from mid-October, before the Caribbean crisis started, Khrushchev’s foreign policy chief Anastas Mikoyan had kept Liu Xiao abreast of the Soviet Union’s nuclear build-up in Cuba. Throughout the entire Cuban Missile Crisis, China stopped all propaganda blitzes against “Soviet revisionism” and condemned “American blackmail and conspiracy” against the “heroic people of Cuba.” To Moscow, this was a great sign of support from Beijing, considering the ongoing fierce ideological bickering between CPSU and CCP at the time.

However, the peaceful settlement of a nuclear showdown between the Soviet Union and the United States over the Cuban missile crisis infuriated Mao in Beijing. Mao took Khrushchev by surprise after the Cuban crisis was over: the CCP suddenly began a hysterical outcry against Khrushchev’s cowardly “capitulationism” to the Americans and Moscow’s “sellout of the Cuban people.” Even at this time, Khrushchev still tried to suck up to Mao: as late as November 3, Khrushchev was still urging Indian Prime Minister Nehru to accept the Chinese terms to settle the Sino-Indian War.

But within days, after the Chinese dramatically intensified their attacks for his cowardice in Cuba, Khrushchev finally had enough of Mao and informed the Indians that he would restart the MiG-21 program with New Delhi.

Beijing took Khrushchev’s about-face seriously and began to withdraw its troops from the disputed area. On Indian’s part––despite being deeply humiliated by the Soviets for Moscow’s perfidious support of the Chinese position and for its suspension of the MiG-21 program when India desperately needed it––Nehru was delighted to see Khrushchev’s change of mind, and also wanted to play the U.S. card by requesting American air force assistance on November 19. While President Kennedy did not agree to Nehru’s request for the 12 American fighter aircraft squadrons, he did warmly welcome India’s friendly gesture and agreed to supply the Indians with meaningful air assistance immediately, ordering U.S. Navy assets to approach the Indian Ocean near India.

The Chinese documents have shown that it was the prospect of both the United States and the Soviet Union, now freed from Cuban entanglement, getting behind India during a border war that prompted Mao to withdraw his troops and end the conflict.

On November 21, 1962, the day after the United States ceased all quarantine actions against the Soviets in the Caribbean, thus effectively ending the Cuban Missile Crisis, Mao Zedong suddenly ordered a complete, unilateral ceasefire and withdrawal from the more than two-thousand-mile border with India, ending China’s largest foreign war since the Korean conflict.

Khrushchev would go on the offensive and made an emotional speech to the Supreme Soviet on December 12, blasting the Chinese for aggression in the Sino-Indian dispute and for China’s opportunist stand during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Mao was furious over Khrushchev’s fiery words on this matter and launched an ideological propaganda campaign known as the Nine Commentaries against Khrushchev’s revisionism and the Soviet Union’s “phony communism.”

What has conditioned the CCP to take military actions has always been the CCP’s unflinching devotion to Marxist-Leninist ideological purity. The 1962 war with India was no exception.