- Economics

- Energy & Environment

- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- Health Care

- US

- Military

- Contemporary

- Security & Defense

- US Defense

- Terrorism

- History

The United States has launched a noble experiment in national security. AFRICOM, the U.S. Africa Command, is an ambitious rethinking of the military’s role not only in Africa but in the world at large. The new separate command for Africa is intended to move beyond Cold War arrangements, which saw the continent divided among three U.S. regional military commands, and to tackle both new and lingering geopolitical problems. Africa Command was created in February 2007 and began initial operations last October; it is scheduled to assume responsibility for all military relationships, programs, and activities in Africa this fall under its first commander, U.S. Army General William E. “Kip” Ward.

Will it succeed? To do so, AFRICOM will have to break free of four bad habits of the U.S. government, each of which tends to reinforce the others. So far, it has broken free only of the first.

OVERDUE ATTENTION—BUT WHAT KIND?

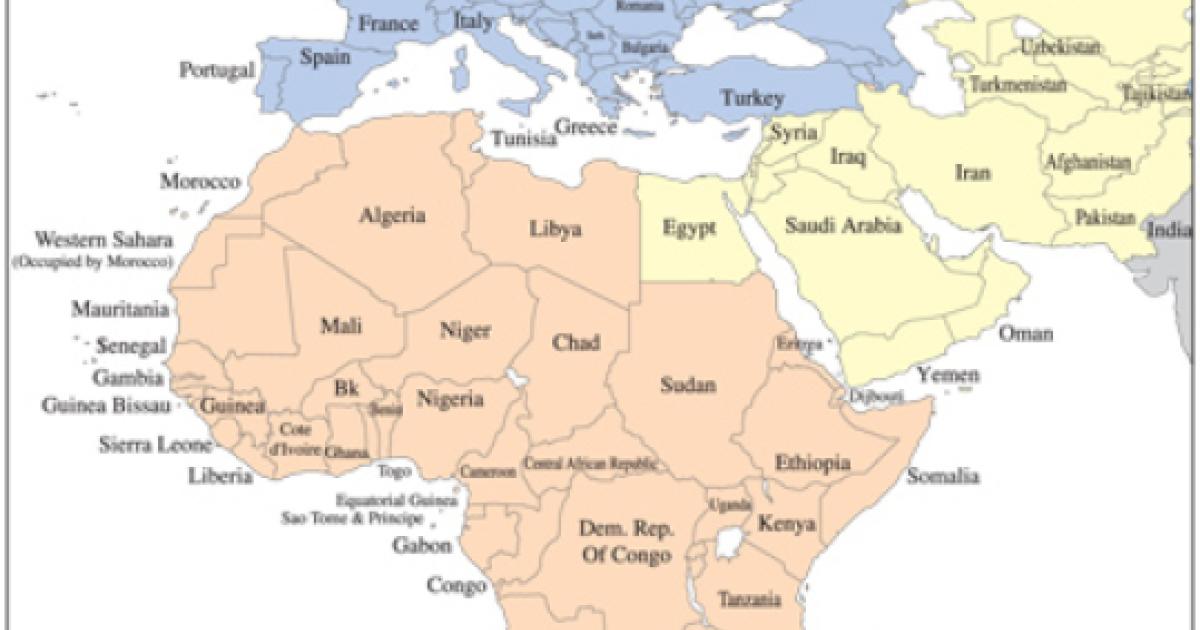

Africa has long been the backwater of U.S. foreign policy. Symbolically, responsibility for Africa was shared among European Command (EUCOM), Central Command (CENTCOM), and Pacific Command (PACOM). AFRICOM now takes responsibility for all of Africa save Egypt, which is considered part of the Middle East (CENTCOM turf ). In the words of one of its architects, Ryan Henry, principal deputy undersecretary of defense for policy, “Instead of having three commanders who deal with Africa as a third or fourth priority, we will have a single commander who deals with it day in and day out as his first and only priority.” AFRICOM breaks a long-standing habit of overlooking Africa and its needs.

A dedicated command for Africa both raises and reflects the continent’s rising importance in U.S. foreign policy and national security. (General James Jones, former chief of European Command, said in 2006 that African issues took up more than half of his personnel’s time.) Africa Command will allow the United States to work the “seams” between EUCOM and CENTCOM. The Darfur conflict, for instance, spills across the border between Sudan and Chad; under the old scheme, the former was part of CENTCOM and the latter part of EUCOM.

But merely giving Africa its own place at the strategic table does not tell us why it is important. This is where the trouble starts.

The second bad habit is the framing of African security issues from the outside. The unified command concept was a child of the Cold War: it enabled a coordinated response to the Soviet Union’s global threat. Africa did not typically play a major role in the East-West conflict and so could be folded into three commands based elsewhere. M

September 11 was the midwife to AFRICOM. The birth of Africa Command acknowledges Africa’s growing strategic importance in the post-9/11 world. Unfortunately, as a new sibling of the existing unified commands, which were created for the Cold War security environment, AFRICOM inherits the genetic defect of an outdated strategy. As Africans see it, on the Cold War security canvas African security was a mere backdrop for the East-West conflict; today, they remain concerned that their security is defined by U.S. concerns.

To take one example, Congress in 2004 authorized an advisory panel of African experts to identify U.S. strategic interests in Africa. The advisers emphasized five concerns: terrorism, oil, armed conflict in “ungoverned spaces,” global trade, and HIV/AIDS. The first two are the drivers behind AFRICOM (although the command’s website spells out a broader mission), yet neither terrorism nor oil is central to Africa’s perception of its own wellbeing. Africa’s post–Cold War conflicts, responsible for millions of deaths, center instead on security and development.

Terrorism, in particular, strikes many Africans as a U.S. concern, not a threat to Africa. Although the 1998 terrorist attacks on the U.S. embassies in Dar es Salaam and Nairobi killed more Africans than Americans, the bombings were widely seen as attacks on the United States rather than on Tanzania or Kenya. Moreover, the U.S. war on terrorism is sometimes seen as a global war on Muslims. As senior Kenyan diplomat Bethuel Kiplagat said, Washington “equates terrorism with Islam.”

As for oil, a new resource war in Africa is seen as the inevitable complement to the war on terror and as yet another area where Africa’s needs take second place. African oil went from 14.5 percent of U.S. oil imports in 2000 to 20 percent last year. Washington’s goal is to increase that amount to 25 percent, largely to lessen dependence on Middle Eastern oil. This oil goal has created the perception, within both the United States and Africa, of a growing geopolitical competition with energy-hungry China. Africa, again, is the backdrop of a gathering storm between great powers. As the proverb says, “When elephants fight, the grass suffers.”

These misgivings explain in part why AFRICOM, which depends on partnerships with African countries, has had at best a tepid reception. (How AFRICOM was launched, with little notice or participation by African nations, is another part of the problem.) In October 2007, members of the Pan-African Parliament, the legislative body of the African Union, approved a motion that no African country should host AFRICOM. Although Liberia’s president, Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf, has offered to host its headquarters, AFRICOM will stay put for now in Stuttgart, Germany, alongside EUCOM headquarters.

TRANSLATING GOALS INTO ACTION

The third bad habit is an outdated way of defining U.S. national security threats, and here AFRICOM issues a direct challenge to entrenched thinking. Even as oil and the war on terrorism, the two strategic interests addressed above, seem to define AFRICOM’s mission, the Pentagon has tried to break free of the conventional definition of a security threat. The AFRICOM website (www.africom.mil) includes these points in its definition of Africa’s strategic interests: ungoverned spaces, endemic corruption, weak governance, poverty, and HIV/AIDS. The Defense Department, therefore, sees AFRICOM’s mission expansively, moving well outside the ambit of war fighting to include, in particular, war prevention.

AFRICOM has been defined as a combatant command “plus,” that is, hard power plus soft power, the latter consisting of state building and conflict prevention, what the military calls phase zero. General Ward, the AFRICOM commander, views this as a three-pronged approach combining efforts by Defense, State, and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). This is sometimes called the 3D approach, for diplomacy, defense, and development.

The mission of Africa Command derives from analyses such as the 2002 U.S. National Security Strategy, which argued that conflict prevention is more important than combat. That report also stated that “America is now threatened less by conquering states than we are by failing ones.” A 2007 Pentagon directive also stressed that stability operations are a “core U.S. military mission.”

AFRICOM attempts to put some meat on the bones of this thinking. Its success will be measured by the wars it does not have to fight.

But old habits die hard. Even as the United States expounds on the importance of Africa, it continues to embrace a strict dichotomy between humanitarian crises and strategic issues. Recent reports by the Council on Foreign Relations expanded the definition of security to include what are sometimes labeled “new security” issues—human rights, global health, economic development, and so on—but the reports continued to reinforce the firewall between humanitarian and strategic reasons for action. In reality, and implied in AFRICOM’s evolving structure, there is no clear division in Africa’s crises.

A Place for Africa

What are these problems that call for blended humanitarian and strategic missions? Consider Africa’s “first world war,” which centered on the Democratic Republic of the Congo but was triggered by the 1994 Rwanda genocide. Similarly, the genocide in Darfur is part of a regional conflict that encompasses Sudan and Chad and could spread to the oil-producing countries of West Africa. As is common in Africa, war and humanitarian crisis are inseparable. A true redefinition of U.S. interests would transcend this false dichotomy.

TURF WARS AND COMPETING PRIORITIES

The fourth, and possibly most debilitating, bad habit could strangle the AFRICOM experiment in its cradle.

U.S. government agencies may have a vested interest in the anachronistic division of humanitarian and strategic concerns. Even as a holistic view of security gains currency within departments that have responsibility for policy toward Africa, each has institutional reasons to preserve the old distinctions. USAID official Michael E. Hess testified before the Senate in August 2007 that a growing U.S. military presence in Africa “has the potential of blurring the lines between diplomacy, defense, and development.” These lines may exist in Washington, but like the borders between African states as created in Berlin in 1885, they carry less meaning in Africa. Hess argued that AFRICOM should “focus on the security sector, while supporting USAID in mutually agreed-upon activities.” He missed the point: AFRICOM is challenging the very definition of security.

Putting AFRICOM’s unique approach to national security into practice calls for expanding the military’s traditional mission, commensurate with a broader notion of security. It demands the blurring of borders around sacred territory belonging to the State Department, USAID, and other agencies. Still, there is legitimate concern, in both the United States and Africa, over the militarization of development and diplomacy implied in AFRICOM’s mission. “Within the State Department and USAID, there is widespread apprehension that AFRICOM will overwhelm civilian-led policy leadership and the interagency process,” J. Stephen Morrison, director of the Africa program for the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told the Senate last year.

Or, as Thomas Barnett wrote last year in Esquire, “They can’t help but feel like their turf ’s being invaded by the gun-toting crowd, hell-bent on opening a new front in a new war.”

AFRICOM is meant to draw together the military and civilians. Its staffing plan, for example, originally called for civilians to make up as much as a fourth of its command personnel. A senior U.S. diplomat, Ambassador Mary Carlin Yates, was appointed deputy to the commander for civilmilitary activities. Yates is the first civilian to hold such a position in a unified command, and she serves alongside a military counterpart. But AFRICOM has had trouble filling its nonmilitary billets, especially in key leadership positions, and has had to scale back its expectations. A recent article in Government Executive said that as of September 30, the target date for AFRICOM to begin full operations, “Defense expects to have only thirteen of the fifty-two interagency command positions, or about 1 percent of the overall staff slots, filled by representatives from non-Defense agencies.”

Staffing problems aside, the new unified command does have successful precedents. The Combined Joint Task Force for the Horn of Africa (CJTFHOA) has worked with nongovernmental organizations to provide medical supplies to Ugandan forces. It conducts civilian-military operations throughout East Africa, digging wells, building schools and hospitals, and repairing roads. CJTF-HOA is a test case for the 3D approach to security that AFRICOM intends to carry out, and many see it as a success.

“There is always something new out of Africa,” wrote Pliny the Elder. The security issues in Africa call for a fresh approach. AFRICOM’s rollout has been awkward, and many issues remain to be resolved, within the United States and between America and its African friends. But it’s time to start breaking old institutional habits that reflect the demands of a bygone era.