The assassination of General Enrico Tellini in August 1923 and the subsequent Corfu incident formed a pivotal moment in early interwar diplomacy, exposing both the aggressive ambitions of Fascist Italy and the systemic weaknesses of the League of Nations. The events unfolded against the background of Greece’s geopolitical collapse following the Asia Minor disaster of 1922, which had produced massive refugee flows, financial ruin, and political instability. Italy, meanwhile, emerged from the First World War embittered by what it viewed as an incomplete victory, and Mussolini’s government was eager to assert its influence in the Balkans and eastern Mediterranean.

The assassination occurred during the work of a diplomatic commission convened to determine the Greek–Albanian frontier, part of the post-war territorial realignment overseen by the Lausanne Conference. Tellini, appointed head of the Italian delegation, was widely perceived in Greece as favoring Albanian territorial claims, reflecting Rome’s strategic goal of limiting Greek sovereignty in Epirus. Greek officials protested repeatedly, arguing that the commission’s terms and direction were biased, deepening mistrust between Athens and Rome.

On August 27, 1923, as the Italian group traveled through rugged terrain near Kakavia, gunfire erupted and Tellini, several officers, and their Greek driver were killed. Although the attack technically occurred on Albanian soil, both Greece and Albania denied responsibility and attributed the assault to armed bands that routinely operated across the porous border. Italy rejected such explanations and asserted—without presenting evidence—that Greece bore direct responsibility.

Detailed investigations of the attack site revealed little of evidentiary substance. Cartridge cases, footprints, and disturbed terrain were interpreted differently by each party. Greek reports emphasized that the mission was attacked by Albanian irregulars; Italian authorities insisted on Greek complicity or negligence. Contemporary press coverage likened Mussolini’s demands to Austria–Hungary’s ultimatum to Serbia in 1914, suggesting Europe had not absorbed the lessons of the Great War.

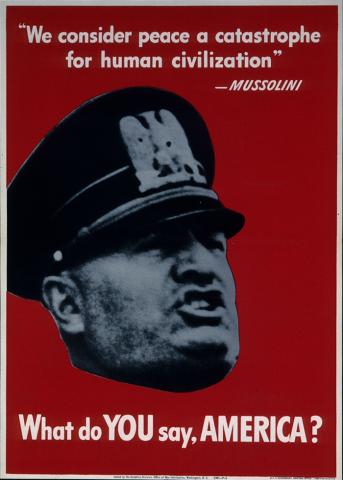

The ambiguity surrounding the perpetrators allowed Mussolini to transform the incident into a diplomatic confrontation. Italy issued a harsh ultimatum demanding a public apology, severe penalties, indemnities, and even executions. Unable to accept these terms, Greece appealed to the League of Nations for arbitration, convinced that the newly created system of collective security would protect it from unilateral coercion. Italy bypassed the League entirely: Mussolini used the assassination as justification for mobilizing naval forces and pressuring Greece militarily.

Within days, Italian warships appeared off Corfu—evidence that planning for intervention had begun even before the assassination. On August 31, without waiting for Greek replies or League deliberations, the Italian navy bombarded Corfu’s capital, killing civilians, damaging buildings, and sparking mass panic among the island’s population, many of whom were already refugees from Asia Minor. Italian forces rapidly occupied the island, encountering almost no resistance from Greece’s depleted and demoralized military.

The Corfu occupation caused international outcry and marked the League’s first major crisis. Britain and France were divided: while Britain favored collective action and respect for sovereignty, France—seeking Italian support in Europe—proved reluctant to confront Mussolini. Under pressure, a compromise emerged: Italy would withdraw but Greece, despite maintaining its legal innocence, would nevertheless pay an indemnity. The settlement preserved peace in the short term but made clear that the League lacked enforcement power against a revisionist great power determined to deploy force.

The crisis also demonstrated Italy’s wider strategy. Long before the attack, Mussolini had prepared military assets in the Adriatic and Ionian Seas, viewing Greece as militarily vulnerable and diplomatically isolated. The rapid seizure of Corfu served dual purposes: to punish Greece symbolically and to display Fascist Italy’s aspiration to regional hegemony. Mussolini framed the action as a defense of order and honor; critics across Europe condemned it as an act of predatory imperialism.

Corfu remained under Italian control for nearly a month. Once diplomatic objectives were achieved and international scrutiny intensified, Italy evacuated the island on September 27, 1923. Yet the withdrawal did not negate the larger implications. Italy had succeeded in coercing an indemnity, demonstrated the limits of post-war international law, and revealed that force remained a viable instrument of policy despite the League’s existence.

For Greece, the incident deepened political insecurity and underscored the need for military and diplomatic modernization. For Europe, the crisis revealed a dangerous precedent: unilateral action by a revisionist state would go largely unpunished. Many analysts later viewed the Corfu episode as an early manifestation of the fascist challenge to the Versailles–Lausanne order and a precursor to the wider destabilization of the 1930s. The Tellini murder thus became more than a localized border incident; it was a signal event marking the fragility of interwar peace and foreshadowing the escalation of authoritarian power politics.