- US Labor Market

- Economics

- Law & Policy

- Regulation & Property Rights

- Budget & Spending

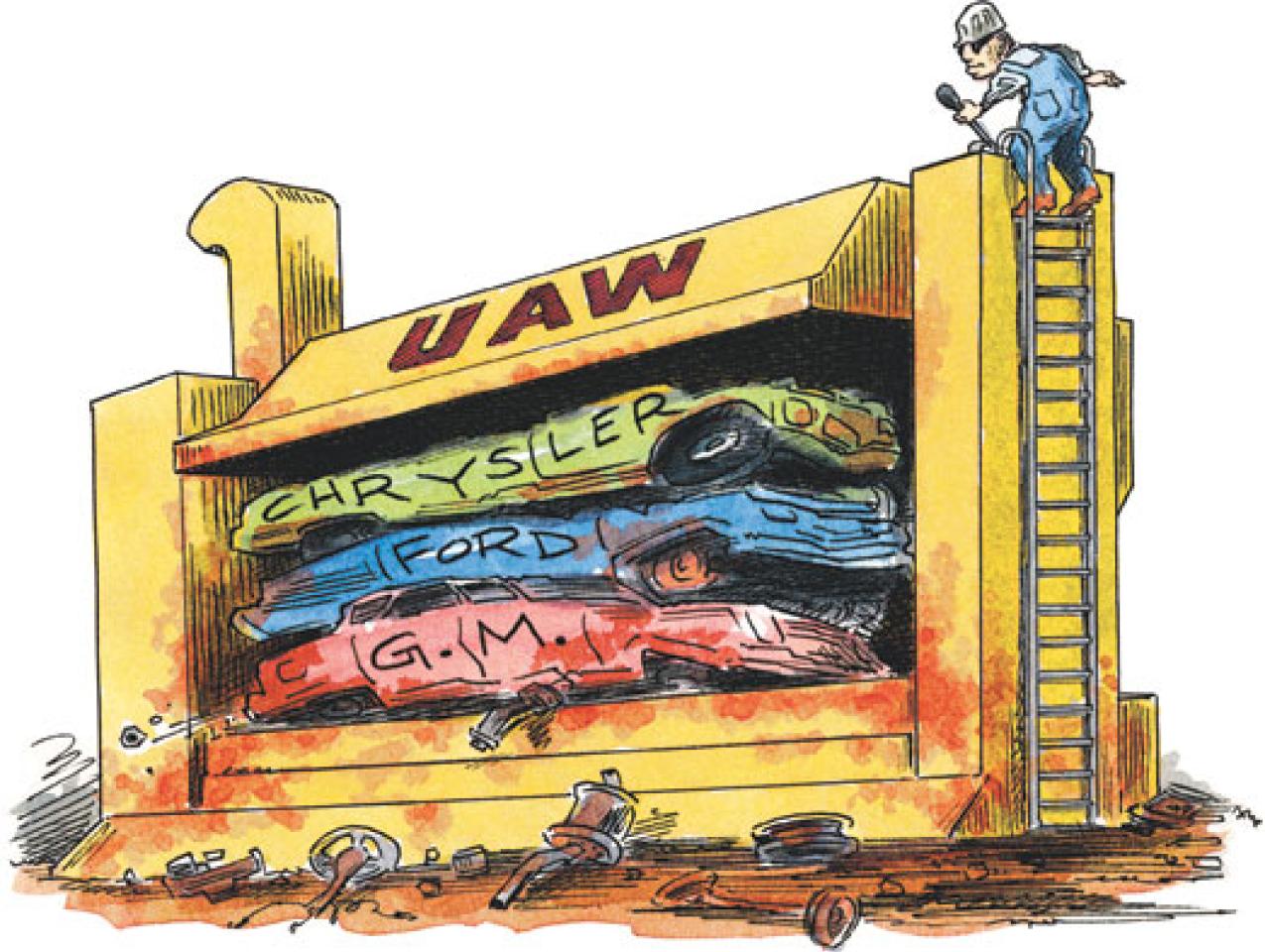

One reason for the financial burdens of the Detroit automakers (General Motors, Chrysler—and Ford, which also appears insolvent, despite its denials) is that their workers are paid higher wages, and receive much more generous benefits paid for by their employer, than the workers employed at automobile plants, mainly in the South, owned by Toyota, Honda, and other foreign manufacturers. The total wage and benefit bill for the Detroit automakers is about $55 an hour, compared to $45 for workers in the foreign- owned plants, and the difference is plausibly ascribed to the fact that the Detroit automakers are unionized and the “foreign transplants” are not. (The comparison excludes retiree benefits, a large expense for the Detroit companies but not an hourly labor cost.)

This difference may seem small, considering that labor is only about 10 percent of the cost of making a car, but many of the workers at the companies that supply parts to the automakers (and the parts represent about 60 percent of the total cost of manufacturing the vehicle) also are represented by the United Auto Workers Union. Because the foreign transplants have competitive advantages over the Detroit automakers in addition to payroll, Detroit can hardly afford to have even slightly higher labor costs.

When the auto bailout bill was first debated in Congress in November, Senator Bob Corker of Tennessee said he would support the bill if it forced the Detroit automakers to reduce wages and benefits (the union would have to agree) to the level at the foreign-owned plants and to make Detroit’s work rules conform to those in the nonunionized plants. The work rules must not be underestimated: as is common in unionized firms, the United Auto Workers has negotiated not only for wages and benefits for the workers it represents but also for rules governing what tasks the workers can and cannot perform, how many workers must be assigned to a particular task, the order in which workers are to be laid off (usually starting with the least senior workers, who tend to be weaker supporters of unionization, have better prospects for employment elsewhere, and don’t worry as much about job security), discipline, and so forth. These work rules not only make it difficult for a firm to optimize its use of labor but also, like the higher wages and benefits that unions obtain, add to the company’s labor costs relative to those of its nonunion competitors.

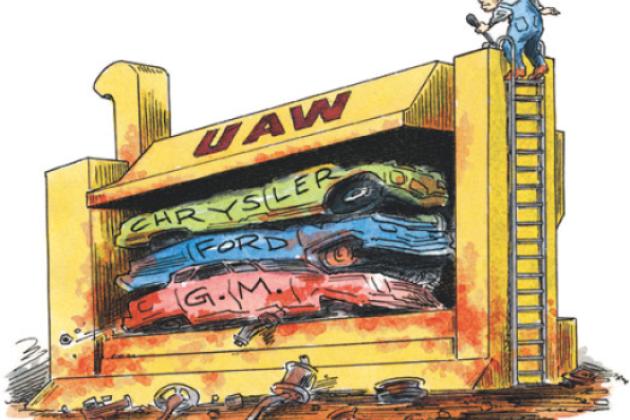

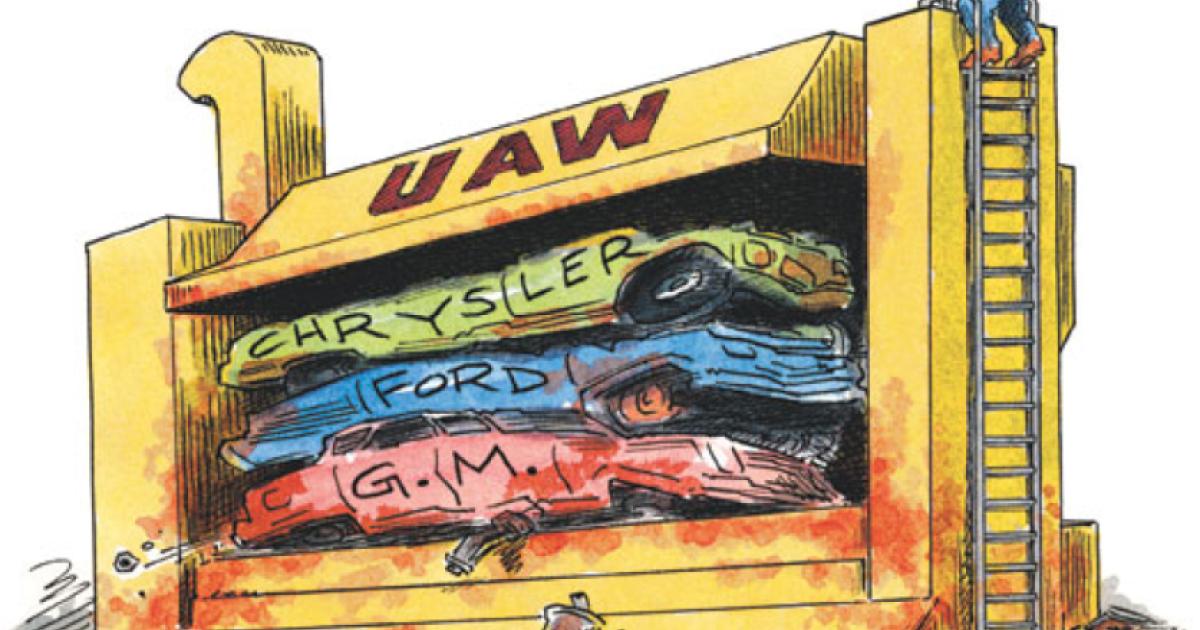

Unions’ goal is to redistribute wealth from the owners and managers of firms, and from workers willing to work for very low wages, to unionized workers and union officers. Unions do this by organizing (or threatening) strikes that impose costs on employers. Employers make a reasoned decision to avoid the costs of a strike by accepting higher wages and benefits and restrictive work rules (provided those costs are lower than the costs of a strike). Because the added cost to the employer of a unionized workforce is a marginal cost (a cost that varies with the output of the firm), unionization results in reduced output by the unionized firm and therefore benefits nonunionized competitors. Unless those competitors are too few or too small to be able to expand output at a cost no higher than the cost to the unionized firms, unionization will gradually drive the unionized firms out of business.

Unions, in other words, are worker cartels. Workers threaten to withhold their labor unless paid more than a competitive wage (including benefits and work rules). Unless their union is able to organize all the major competitors in a market, however, the cartel will be eroded by the entry of nonunionized firms, which will offer lower labor costs. The parallel to producer cartels is exact—workers are producers.

THE EROSION OF A CARTEL

Labor monopolies in the automobile industry are eroding. The market share of the Detroit automakers has shrunk steadily relative to that of the foreign transplants and with it the number of unionized autoworkers, whose numbers have shrunk by a third or more since 1970. If labor costs force the Detroit automakers into liquidation, the UAW will be out of business too. Workers will no longer be getting anything in exchange for their union dues.

I don’t believe there is much to be said on behalf of unions, at least under current economic conditions. The redistribution of wealth they bring about is not only fragile, for the reasons just suggested, but also capricious because it is only by chance that conditions in a particular industry are favorable or unfavorable to unionization. By driving up employers’ costs, unions cause prices to increase, which harms consumers, who are not on average any better off than unionized workers are. Unions push hard for minimum-wage laws and for tariffs, both devices to reduce competition from workers, in the United States or abroad, who are willing to work for lower wages. Current union hostility to immigrant workers echoes the unions’ former hostility to blacks and women—that is to say, to workers willing to work for pay below the union wage. And by raising labor costs, unions accelerate the substitution of capital for labor, further depressing the demand for labor and hence average wages. Union workers, in effect, exploit nonunion workers, as well as reducing the overall efficiency of the economy. The United Auto Workers has done its part to place the Detroit auto industry on the road to ruin.

ADVERSARIAL AND SHORTSIGHTED

There is also a long history of union corruption (though not in the UAW). And some union activity (though again, not that of the UAW) is extortionate: the union and the employer tacitly agree that as long as the employer gives the workers a wage increase slightly above the union dues, the union will leave the employer alone.

There may be, I grant, cases in which unionization reduces an employer’s labor costs. If there is deep antipathy between workers and employer, perhaps breaking out in violence—with strikebreakers beating up strikers, strikers beating up “scabs,” and sit-down strikers destroying company property— there may be benefits from interposing an organization between employer and workers and creating (as the National Labor Relations Act has done) a civilized mode of resolving labor disputes. But in cases where union organization would be mutually beneficial, the employer would invite the union to organize its workers. I am sure the Detroit automakers would very much like to disinvite the United Auto Workers.

Unions do provide some services that are valuable to employers, such as grievance procedures that check arbitrary actions by supervisory employees. Moreover, union-negotiated protection of senior workers can benefit their employer by encouraging them to share their know-how with new workers, without the fear that by doing so they would be sharing themselves out of a job. But an employer who believes that such steps would reduce his labor costs could take them without the presence of a union.

Mickey Kaus, a blogger who is an expert on the automobile industry, attributes much of the problem with the UAW to the procedures that govern labor relations in unionized plants. “The problem,” Kaus writes in Slate, “is the American adversarial labor-management negotiating system, in which reasonable people doing what the system tells them they should do wind up producing undesirable results. Just as negotiating over work assignments means factories adjust too slowly to generate continuous efficiency improvements (which often involve constantly changing work assignments), negotiating ponderous threeyear contracts . . . means contracts adjust too slowly to save the companies from failure if market conditions change. . . . The $14 wage scale for new hires [to which the UAW agreed several years ago] hasn’t had an impact because nobody new is being hired by the UAW’s employers, who are shrinking, not growing. The obvious alternative to cutting the pay of nonexistent future workers would be to cut the pay of existing current workers—but they are the people the system tells [UAW President Ron Gettelfinger] he needs to please.”

The unions strongly supported the Democrats in the most recent election and are looking for payback. I do think that there are good economic reasons for keeping the Detroit automakers out of bankruptcy until the current depression hits bottom and a recovery begins; until then, the shock to the economy would be too great. That will keep the UAW alive for a while. But if the union resists making substantial concessions to the automakers, hoping that President Obama and Congress will force the automakers’ bondholders to make the necessary concessions or that the taxpayer will be forced to subsidize the automakers indefinitely, it will be playing a game of chicken. The auto bailout is deeply unpopular with the public, and the UAW’s stubbornness may reinforce the impression that unions are dinosaurs slouching toward extinction.