- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

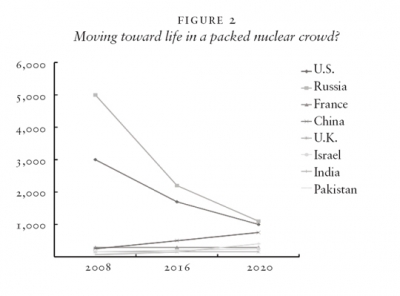

If current trends continue, in a decade or less, the United Kingdom could find its nuclear forces eclipsed not only by those of Pakistan, but of Israel and India as well. Shortly thereafter, France could share the same fate. China, which has already amassed enough separated plutonium and highly enriched uranium to easily triple its current stockpile of roughly 300 deployed nuclear warheads, also is likely to increase its deployed numbers, quietly, during the coming years.1 Meanwhile, over 25 states have announced their desire to build a large nuclear reactor — a key aspect of most previous nuclear weapons programs — before 2030.

None of these trends should be welcome to those who favor the abolition of nuclear weapons. Indeed, unless these negative trends are restrained and reversed, nuclear weapons reductions in the U.S. and even Russia may not be enough to reduce continuing nuclear rivalries and could actually intensify them. To understand why, one need only review what is currently being proposed to reduce these nuclear threats.

The road to zero

A decade ago, an analysis of the challenges of transitioning to a world without nuclear weapons would be dismissed as purely academic. No longer. Making total disarmament the touchstone of U.S. nuclear policy is now actively promoted by George Shultz, William Perry, Henry Kissinger, and Sam Nunn — four of the most respected American names in security policy.2 Most of their proposals for reducing nuclear threats, moreover, received the backing of both presidential candidates in 2008 and, now, with President Obama’s arms control pronouncements in April in Prague, they have become U.S. policy. These recommendations include getting the U.S. and Russia to make significant nuclear weapons reductions; providing developing states with “reliable supplies of nuclear fuel, reserves of enriched uranium, infrastructure assistance, financing, and spent fuel management” for peaceful nuclear power; and ratifying a verified Fissile Material Cut-off Treaty ( fmct) and a Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (ctbt).

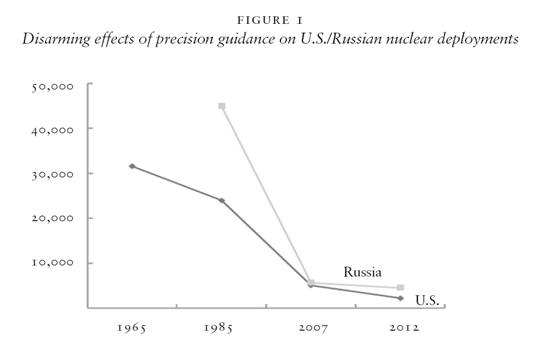

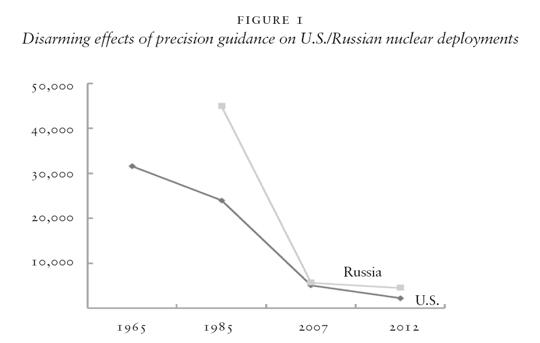

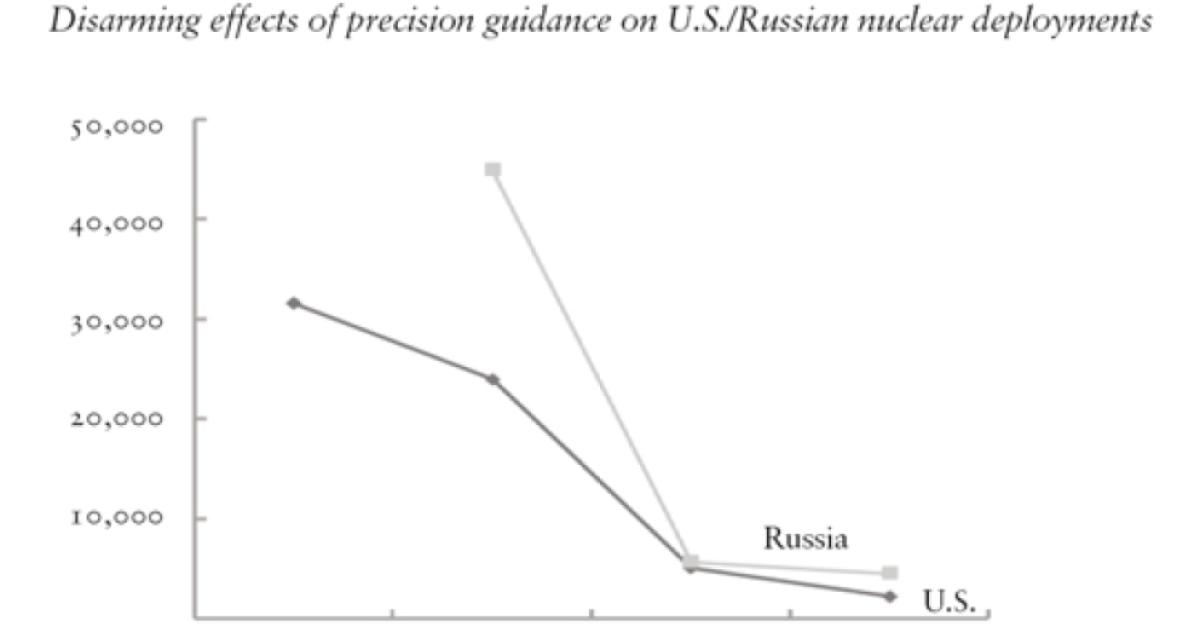

This newfound enthusiasm for nuclear weapons reductions has been heralded as a clear break from the past. Politically, this may be so. Technically, however, the U.S. and Russian military establishments have steadily reduced the numbers of operational, tactical, and strategic nuclear weapons since the late 1960s sevenfold (i.e., from 77,000 warheads to less than 11,000). By 2012, this total is expected to decline by yet another 50 percent.

What has driven these reductions? Mostly, advances in military science. Since the Cold War, progress in computational science, digital mapping, and sensor and guidance technologies have significantly enhanced the precision with which weapons can be aimed. Rather than 50 percent of warheads hitting within 1,000 meters of their intended targets — the average accuracy of the 1960s-design scud missiles — it now is possible to strike within a few feet (the average accuracy of a Predator-launched missile or a long-range cruise missile). Thus, the U.S. and Russian militaries no longer need to target more or larger-yield nuclear weapons to assure the destruction of fixed military targets. They can threaten them with a single, small-yield nuclear weapon or even conventional warheads. Hence, the massive reduction in U.S. and Russian deployed tactical and strategic nuclear weapons and in the average yields of these weapons (see Figure 1).3

When policymakers call for more nuclear weapons reductions and increased nuclear restraint, then, they are hardly pushing against historical or technological trends. Unfortunately, this desired harmony with history and science is far less evident when it comes to the specific proposals being made to reduce future nuclear threats. Here, it is unclear if the proposals will reduce or increase the nuclear threats we face.

Consider the suggestion made in the 2008Nunn-Shultz-Perry-Kissinger Wall Street Journal op-ed (a follow-up piece to one they had written a year earlier) that advocated spreading “civilian” nuclear power technology and large reactors to states that promise to forgo nuclear fuel making — a spread that would bring countries within weeks or months of acquiring nuclear weapons. The U.S. and most other states currently claim that all nations have an “inalienable” right to make nuclear fuel.4 As a result, any state that promises to forgo exercising this right today could legally — once it has mastered how to make weapons-usable plutonium or uranium — change its mind and chemically separate weapons-grade material from its reactor’s spent fuel or enrich the fresh fuel it has on hand without breaking any currently enforced legal requirement. In essence, this is what North Korea did despite pledging in a 1992 North-South denuclearization agreement not to reprocess spent fuel or enrich uranium.

Also, nuclear fuel-making efforts can be hidden. A small, covert plutonium chemical separation line, for example, might be built in a matter of months and, after a week of operation, produce a crude bomb’s worth of weapons-usable plutonium per day. And there are ways that fresh and spent nuclear reactor fuel might be diverted to accelerate a bomb-making program without necessarily setting off any inspection alarms.5 All of this suggests that giving states everything they need to build and operate a large reactor, in exchange for pledges not to divert the technology or reactor fuel to make bombs, risks increasing the nuclear threats we already face.

Two other questionable nuclear threat reduction proposals now championed by arms control proponents include agreeing to a verified fmct and ctbt. Proponents insist that such agreements are sufficiently verifiable to prevent violators from securing any significant military advantage. Such contentions are debatable.6 In the case of a ctbt, critics claim that extremely useful small test explosions could be conducted to validate advanced nuclear weapons designs without necessarily giving off a clear seismic signal and that without such a signal, other nuclear test monitoring improvements fall far short of sufficiency. Worse, they suggest that other nations might gain strategic advantage over the U.S. either by cheating or by interpreting what the ban permits more liberally than Washington does. Finally, they complain that American ratification may still not be enough to bring the treaty into force.7

As for verifying a fmct, a key concern is that it will still allow nuclear weapons states to make nuclear fuel for civilian purposes and that there is no way to reliably detect military diversions from such activities early enough to prevent bomb making. A reasonable rejoinder to this concern is that members of such a treaty would be allowed to keep their existing nuclear weapons stockpiles and so would lack much of a motive to use their civilian nuclear fuel-making plants to cheat. Nonweapons states, such as Iran, however, might well point to such inspections of nuclear fuel-making plants and ask why such casual monitoring cannot be relied upon to prevent military diversions from whatever fuel-making plants they might operate or acquire. Without a good answer to this question, critics note that pushing a fmct could possibly resolve the headache of growing nuclear arsenals in Pakistan, India, North Korea, and China only to create a much larger set of nuclear proliferation dilemmas in the Middle East and Far East.8 In addition, there are serious political obstacles to bringing such a treaty into force: Certainly, Egypt, Pakistan, and others would be loath to join until Israel gave up its nuclear weapons and India no longer presented a significant military threat. For these reasons, even nominal supporters of the fmct have suggested that it may make more sense to promote easier, voluntary “fissile material control initiatives.”9 Critics, meanwhile, suggest that any fmct verification effort be narrowed to cover only those states known to have nuclear weapons.10

A packed nuclear crowd?

So far, these verification battles have been waged on the margins of public policy. Each is likely to become important when and if these specific proposals are implemented. Until then, the debate over further reductions of existing nuclear stockpiles is likely to turn, if at all, on more basic considerations. Two issues immediately come to mind. The first is the assumption that the U.S. and Russia will both continue to reduce their nuclear weapons deployments significantly. The second: That once such reductions are made, one need worry only about accidental use, the further spread of nuclear weapons to additional states, and securing what nuclear material there is against possible theft. Many U.S officials and security and nuclear terrorism experts believe that the U.S. can work with the Russians to reduce the number of operationally deployed nuclear weapons in each country. Some believe that Washington should unilaterally reduce its operationally deployed nuclear weapons to 1,000 or even 500.11

What these optimistic analyses rarely consider, however, is Russia’s increasing reliance on nuclear weapons for its own security and the nuclear weapons production capacities that continue to grow in Pakistan, India, China, and Israel.12 They miss how easy it would be for Russia, China, or the U.S. to enlarge their existing nuclear arsenals quickly by exploiting their existing surplus military stockpiles of plutonium and uranium. Nor have they focused on how rapidly Japan or India might acquire nuclear weapons or ramp up the size of their existing nuclear arsenal by dipping into their growing “civilian” stockpiles of weapons-usable plutonium.

With such large and growing stockpiles of nuclear-weapons-usable materials, achieving true nuclear arms restraint will become more difficult no matter what the actual number of operationally deployed nuclear weapons might be. Indeed, in ten to 15 years, the expansion of Chinese, Indian, Pakistani, and Israeli nuclear capabilities could also make further U.S. and allied nuclear weapons reductions politically more difficult and could well encourage other countries to hedge their security bets by developing nuclear weapons options of their own.

The conventional wisdom, of course, is that these dangers are best addressed by getting the U.S. and Russia mutually to reduce their nuclear weapons capabilities.13 Yet, just as strong is the argument that at some point, the chances for strategic miscalculation (and war) could increase if China, Pakistan, India, and Israel continued to augment their nuclear capabilities and the U.S. and Russia reduced their own. Certainly, as the qualitative and quantitative differences between nuclear weapons states becomes smaller — when such differences are measured in hundreds of weapons rather than thousands of bombs and each state has a large number of missile-deliverable warheads and the long-range rockets and cruise missiles needed to put them on target — security alliance relations and rivalries could become much more sensitive to a variety of security developments.14 Assuming the realization of the road to zero objectives for the U.S. and Russia, the packing of the current nuclear crowd is not far-fetched (see Figure 2):

Fissile for peace and war

Compounding this worrisome prospect are large amounts of weapons-usable materials in military and growing civilian stockpiles that could be quickly militarized to create or expand existing nuclear bomb arsenals. Russia, for example, has at least 700 tons of weapons-grade uranium and over 100 tons of separated plutonium in excess of its military requirements, while the U.S. has roughly 50 tons of separated plutonium and about 160 tons of highly enriched uranium in excess of its military needs. As noted before, China’s surpluses of highly enriched uranium and separated plutonium are already estimated to be large enough to allow Beijing to triple the number of weapons it currently has deployed.15

In addition, stockpiles of civilian materials that could be drawn upon to make additional bombs are large or growing. China, for example, is planning to complete two “commercial” reprocessing plants by 2025 that will be able to produce each year enough material to make at least 1,000 crude nuclear weapons.16 Meanwhile, Japan, a nonnuclear weapons competitor of Beijing, already has roughly 45 tons of separated plutonium (much of which is stored in France), 6.7 tons of which is stockpiled on its own soil — enough to make roughly 1,500 crude nuclear weapons. Japan also will soon be separating enough plutonium at its newest commercial reprocessing plant to make between 1,000 and 2,000 crude-weapons-worth of separated plutonium a year. Almost all of this newly separated plutonium will be in surplus of Japan’s civilian requirements and will be stored in the country.17

As for India and Pakistan, they have no declared military surpluses. India, however, has stockpiled roughly 11 tons of unsafeguarded “civilian” reactor-grade plutonium — enough to make well over 2,000 crude fission weapons — and can easily generate over 1,200 kilograms of unsafeguarded plutonium annually. Pakistan has no such reserve but, like India, is planning to expand its “civilian” nuclear generating capacity roughly twenty-fold in the next two decades and is stockpiling weapons-grade uranium. Both countries are increasing their nuclear fuel-making capacity (uranium enrichment and plutonium reprocessing) significantly.18

Atoms for peace?

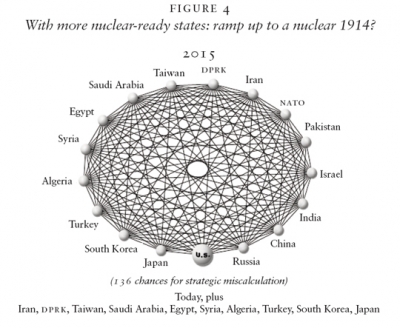

Finally, several new nuclear weapons contenders are also likely to emerge in the next two to three decades. Among these might be Japan, North Korea, South Korea, Taiwan, Iran, Algeria, Brazil (which is developing a nuclear submarine and the uranium to fuel it), Argentina, and possibly Saudi Arabia (courtesy of weapons leased to it by Pakistan or China), Egypt, Syria, and Turkey. All of these states have either voiced a desire to acquire nuclear weapons or tried to do so previously and have one or more of the following: A nuclear power program, a large research reactor, or plans to build a large power reactor by 2030.

With a large reactor program inevitably comes a large number of foreign nuclear experts (who are exceedingly difficult to track and identify) and extensive training, which is certain to include nuclear fuel making.19 Thus, it will be much more difficult to know when and if a state is acquiring nuclear weapons (covertly or overtly) and far more dangerous nuclear technology and materials will be available to terrorists than would otherwise. Bottom line: As more states bring large reactors on line more will become nuclear-weapons-ready — i.e., they could come within months of acquiring nuclear weapons if they chose to do so.20 As for nuclear safeguards keeping apace, neither the iaea’s nuclear inspection system (even under the most optimal conditions) nor technical trends in nuclear fuel making (e.g., silex laser enrichment, centrifuges, new South African aps enrichment techniques, filtering technology, and crude radiochemistry plants, which are making successful, small, affordable, covert fuel manufacturing even more likely)21 afford much cause for optimism.

This brave new nuclear world will stir existing security alliance relations more than it will settle them: In the case of states such as Japan, South Korea, and Turkey, it could prompt key allies to go ballistic or nuclear on their own.

Nuclear 1914

At a minimum, such developments will be a departure from whatever stability existed during the Cold War. After World War II, there was a clear subordination of nations to one or another of the two superpowers’ strong alliance systems — the U.S.-led free world and the Russian-Chinese led Communist Bloc. The net effect was relative peace with only small, nonindustrial wars. This alliance tension and system, however, no longer exist. Instead, we now have one superpower, the United States, that is capable of overthrowing small nations unilaterally with conventional arms alone, associated with a relatively weak alliance system ( nato) that includes two European nuclear powers (France and the uk). nato is increasingly integrating its nuclear targeting policies. The U.S. also has retained its security allies in Asia (Japan, Australia, and South Korea) but has seen the emergence of an increasing number of nuclear or nuclear-weapon-armed or -ready states.

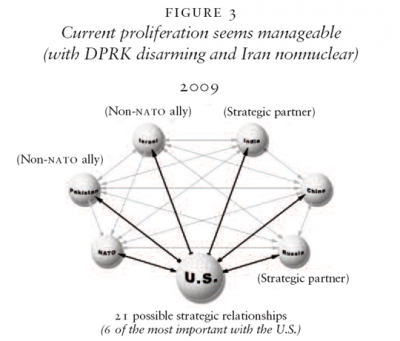

So far, the U.S. has tried to cope with independent nuclear powers by making them “strategic partners” (e.g., India and Russia), nato nuclear allies (France and the uk), “non-nato allies” (e.g., Israel and Pakistan), and strategic stakeholders (China); or by fudging if a nation actually has attained full nuclear status (e.g., Iran or North Korea, which, we insist, will either not get nuclear weapons or will give them up). In this world, every nuclear power center (our European nuclear nato allies), the U.S., Russia, China, Israel, India, and Pakistan could have significant diplomatic security relations or ties with one another but none of these ties is viewed by Washington (and, one hopes, by no one else) as being as important as the ties between Washington and each of these nuclear-armed entities (see Figure 3).

There are limits, however, to what this approach can accomplish. Such a weak alliance system, with its expanding set of loose affiliations, risks becoming analogous to the international system that failed to contain offensive actions prior to World War I. Unlike 1914, there is no power today that can rival the projection of U.S. conventional forces anywhere on the globe. But in a world with an increasing number of nuclear-armed or nuclear-ready states, this may not matter as much as we think. In such a world, the actions of just one or two states or groups that might threaten to disrupt or overthrow a nuclear weapons state could check U.S. influence or ignite a war Washington could have difficulty containing. No amount of military science or tactics could assure that the U.S. could disarm or neutralize such threatening or unstable nuclear states.22 Nor could diplomats or our intelligence services be relied upon to keep up to date on what each of these governments would be likely to do in such a crisis (see graphic below):

Combine these proliferation trends with the others noted above and one could easily create the perfect nuclear storm: Small differences between nuclear competitors that would put all actors on edge; an overhang of nuclear materials that could be called upon to break out or significantly ramp up existing nuclear deployments; and a variety of potential new nuclear actors developing weapons options in the wings.

In such a setting, the military and nuclear rivalries between states could easily be much more intense than before. Certainly each nuclear state’s military would place an even higher premium than before on being able to weaponize its military and civilian surpluses quickly, to deploy forces that are survivable, and to have forces that can get to their targets and destroy them with high levels of probability. The advanced military states will also be even more inclined to develop and deploy enhanced air and missile defenses and long-range, precision guidance munitions, and to develop a variety of preventative and preemptive war options.

Certainly, in such a world, relations between states could become far less stable. Relatively small developments — e.g., Russian support for sympathetic near-abroad provinces; Pakistani-inspired terrorist strikes in India, such as those experienced recently in Mumbai; new Indian flanking activities in Iran near Pakistan; Chinese weapons developments or moves regarding Taiwan; state-sponsored assassination attempts of key figures in the Middle East or South West Asia, etc. — could easily prompt nuclear weapons deployments with “strategic” consequences (arms races, strategic miscues, and even nuclear war). As Herman Kahn once noted, in such a world “every quarrel or difference of opinion may lead to violence of a kind quite different from what is possible today.”23 In short, we may soon see a future that neither the proponents of nuclear abolition, nor their critics, would ever want.

None of this, however, is inevitable.

Making something of zero

The u.s. government is now committed to moving closer to zero nuclear weapons. The challenge, however, is not whether the U.S. can reduce the numbers of nuclear weapons it has deployed or stored. It has been reducing these numbers steadily since 1964. Instead, the question now is how the U.S. might reduce these numbers without simultaneously increasing other states’ interest in acquiring nuclear weapons capabilities of their own.

Here, it would be helpful to keep four principles in mind:

First, it’s critical to avoid making the wrong sorts of military reductions or additions. At a minimum, any push for further nuclear reductions must be as proportionate as possible. To maintain or extend the security alliances that are currently neutralizing states’ demands to go nuclear, the U.S. must not only roughly preserve or improve the relative correlation of forces between it and its key nuclear competitors, China and Russia, but do all it can to keep states that might compete in the nuclear arena with these competitors from doing so.

If Washington decides to reduce the operational deployment of additional U.S. nuclear weapons, then it must see to it that additional nuclear restraints — either nuclear deployment reductions or further weapons-usable fuel stockpile or production limits — are imposed not only on Russia, but China, India, and Pakistan as well. As a practical matter, this will mean that other nuclear-weapons-ready states — including Israel, Japan, and Brazil — also should be urged to curtail or end their production of nuclear-weapons-usable materials.

Here, it also would be important for the U.S. to make sure that implementation of its newly struck civilian nuclear cooperative agreement with India does not end up helping New Delhi make more nuclear weapons than it was producing before the deal was finalized late in 2008. Under the npt, nuclear weapons states are forbidden to help states that did not have nuclear weapons before 1967 acquire them. Also, under the Hyde Act, the executive is required to report to Congress just how much nuclear fuel India is importing, how much of this fuel India is using to run its civilian reactors, how much uranium fuel India is producing domestically, and the extent to which India is expanding its unsafeguarded plutonium stockpiles. If the amount of unsafeguarded nuclear fuel available to India to make bombs grows as a result of increased imports of safeguarded reactor fuel, the U.S. would be implicated in violating the npt along with Russia and France. In this case, the U.S. would be bound to ask these other states to suspend supplying some or all of the nuclear fuel they might be selling to India.24

As for trying to maintain the relative correlation of forces between nuclear armed states through military means, considerable care will be required. Missile defenses, for example, could help compensate for eliminated U.S. nuclear weapons systems. Instead of “neutralizing” a possible opponent’s nuclear missile by targeting it with a nuclear weapon, it could be possible to do so in a non-nuclear fashion assuming missile defenses become effective and affordable enough. Yet, even if such defenses do grow to be inexpensive and effective, it would not necessarily improve matters to deploy them in equal amounts everywhere and anywhere.

Consider the case of India and Pakistan. Because Pakistan has not yet fully renounced first use and India will always have conventional superiority over Islamabad, Pakistan would actually have good cause to feel less secure than it already does if equal levels of missile defense capabilities were given to both sides. Similarly, Pakistan would have far more to fear than to gain if the U.S. offers to afford India and Pakistan equal amounts of advanced conventional capabilities since these might conceivably enable New Delhi to knockout Islamabad’s nuclear forces without using nuclear weapons. How the U.S. and others enhance each of these states’ offensive and defensive military capabilities, then, matters at least as much as what each is offered.25

Another nuclear weapons substitution option now being discussed is to employ long-range precision strike systems in place of eliminated nuclear systems. These systems’ effectiveness against hardened or hidden targets is unclear, however. There also may be concerns about how they could be used without unintentionally triggering a nuclear response. What might the numbers and the effectiveness of such nonnuclear offensive and defensive systems have to be to substitute for eliminated nuclear weapons systems?

Second, there must be a clear cost for violating existing nuclear control agreements and understandings. The U.S. and other likeminded states have yet to clearly establish that nuclear proliferation does not pay. To the contrary, the cost for the worst nuclear violators — Iran and North Korea — has either been light or nonexistent. It is highly unlikely that North Korea will give up all of its nuclear weapons. It also may be too late to prevent Iran from acquiring nuclear bombs. The prize now is to make sure that North Korea’s and Iran’s nuclear misbehavior does not become a model for others. Certainly, allowing Tehran to continue to make nuclear fuel under more “intrusive” inspections (even though there is no reliable way to safeguard such activity from being diverted to make bombs) would be self-defeating.

Given that China and Russia cannot be counted on to join the U.S., France, and others to significantly tighten trade sanctions against Tehran, the only choice Washington and its allies have is either to back down or to try to isolate and further stigmatize Iran’s nuclear behavior as best they can without additional support from the United Nations Security Council. This would require the waging of a type of Cold War not unlike the U.S. and its key allies waged against the Warsaw Pact, the apartheid government in South Africa, and Libya.

The U.S. and other like-minded states should also try to establish “country-neutral” sanctions in domestic and international law. These sanctions should be directed against states that cannot be found to be in full compliance with their nuclear safeguards obligations, that violate them, or that would withdraw from the npt before coming back into full compliance. Rather than placing the burden on the iaea Board of Governors, the Nuclear Suppliers Group, or the un Security Council to reach a consensus on the sanctions for such transgressions, a minimal, predetermined list should be automatically imposed.

Third, it is critical to distinguish between nuclear activities and materials that the IAEA can reliably safeguard against military diversions and those that it cannot. The npt is clear that all peaceful nuclear activities and materials must be safeguarded — that is, inspected in such a way as to prevent them from being diverted to make nuclear weapons. Most npt states have fallen into the habit of thinking that if they merely declare their nuclear holdings and activities and allow international inspections, they have met this requirement.

This is a prescription for mischief. After the nuclear inspections gaffes in Iraq, Iran, Syria, and North Korea, we now know that the iaea cannot reliably detect covert nuclear activities. We also know that the iaea and euratom annually lose track of many bombs’ worth of usable plutonium and uranium at declared nuclear fuel-making plants. We also know that the iaea cannot assure continuity of inspections for spent and fresh fuel rods at more than half of the sites that it inspects. Finally, we know that declared plutonium and enriched uranium can be made into bombs and their related production plants diverted so quickly (in some cases, within hours or days) that no inspection system can afford timely warning of a bomb-making effort.

All of these points fly directly in the face of the kind of early alarms nuclear safeguards must provide. Any true safeguard against military nuclear diversions must reliably detect them early enough to allow outside powers to intervene to block a bomb from being built. Anything less is only monitoring that might, at best, detect military diversions after they occur. Given the inherent limits to the kind of warning iaea nuclear inspections can provide, the iaea needs to concede that it cannot safeguard all that it inspects.

Such candor would be most useful. It would immediately raise first-order questions about the advisability of producing or stockpiling plutonium, highly enriched uranium, and plutonium-based reactor fuels in any but the nuclear weapons states. At the very least, it would suggest that nonweapons states ought not to acquire these materials or facilities beyond what they already have.

Where would one raise these points? A good place to start would be the npt Review conference that will be held in May 2010. In advance of the conference, the U.S. and other likeminded nations independently might assess whether or not the iaea can meet its own inspection goals; under what circumstances (if any) these goals can be met; and, finally, whether these goals are good enough. This work would cost very little and could be undertaken immediately without legislation or any new international agreements.

Fourth, if we want to develop safe, economically competitive forms of energy, we should discourage using additional government financial incentives to promote new civilian nuclear projects. Supporters of nuclear power insist that its expansion is critical to prevent global warming. The proof is to be had in determining what new nuclear power plants will cost in comparison to their alternatives while factoring in the price of carbon. Creating more government financial incentives specifically geared to build more nuclear plants and their associated fuel-making facilities will only make this more difficult to do. Not only do such subsidies mask the true costs of nuclear power, they tilt the market against their alternative. This is troubling since the most dangerous forms of civilian nuclear energy — nuclear fuel making in most nonweapons states and large power reactor projects in war-torn regions like the Middle East — turn out to be poor investments as compared to much safer alternatives.26

There are three ways to prevent or mitigate such dangerous market distortions. The first would be to get as many governments as possible to offer proposed civilian energy projects that would compete openly against possible, nonnuclear alternatives. This is hardly a radical proposal. France, the U.S., and the iaea have all quietly noted that nuclear power programs only make sense for nations that have a large electrical grid, a major nuclear regulatory and science infrastructure, and proper financing. U.S. officials have emphasized how uneconomical Iran’s nuclear program is in the near- and mid-term as compared to developing Iran’s existing natural gas resources. In the U.S., private banks refuse to invest to build new nuclear power plants unless they secure federal loan guarantees and new, additional subsidies. After an extensive analysis in 2006, the British government found, in contrast, that if carbon emissions are properly priced (or taxed), British nuclear power operators should be able to cover nearly all of their own costs without government support.27

Economic judgments and criteria, in short, are already being relied upon to judge the merits of proposed nuclear projects. The U.S. and most other nations, however, should go further. Most advanced nations, including the U.S., claim to back the principles contained in the Energy Charter Treaty and the Global Charter on Sustainable Energy Development. These international agreements are designed to encourage all states to open their energy sectors to international bidding and to assure that as many subsidies and externalities are internalized and reflected in the price of any energy option.28 The U.S. claims it is serious about reducing carbon emissions in the quickest, least costly manner. If so, it also would make sense to reference and enforce the principles of the Energy Charter Treaty and the Global Charter on Sustainable Energy as a part of the follow-on negotiations to the Kyoto Protocol.

As a second and complementary effort, the United States should work with developing states to create non-nuclear alternatives to address their energy and environmental needs. In the case of the U.S., this would merely entail following existing law. Title v of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Act of 1978 requires the executive branch to do analyses of key countries’ energy needs and identify how these needs might be addressed with non-fossil, non-nuclear energy sources. Title v also requires the executive branch to consider the creation of an energy-focused “Peace Corps” to help developing nations explore these alternative options. To date, no president has chosen to implement this law. The U.S. Congress has indicated that it would like to change this beginning by requiring Title v country energy analyses (and outside, nongovernmental assessments of these analyses) to be done as a precondition for the U.S. initialing any new, additional nuclear cooperative agreements. Here, the U.S. can lead by example.29

Finally, although it may not be immediately possible to get all nations to agree about what is “peaceful” and protected under the npt, it would be useful to try by insisting that such projects ought to be safeguardable and beneficial. But it will be impossible to persuade even one state of this proposition if the U.S. continues to insist that all states have an inalienable right to the most dangerous nuclear materials, equipment, and technology so long as they have some conceivable civilian application and are declared and inspected. The U.S. should stop making this case and instead build on the argument it already has made that there is no duty for any nuclear supplier state to supply dangerous technologies or materials under the npt. Specifically, the U.S. should explain that what is peaceful and protected under the npt can only be determined on the basis of a number of factors, including whether or not the material, equipment, and technology can be reliably safeguarded against possible military diversions and if the project that they are dedicated to is economically justifiable.

Certainly, there is nothing in the npt that requires member states to read the treaty as if they must encourage countries to come to the very brink of acquiring bombs by developing dangerous, money-losing nuclear ventures. In fact, one would hope that most states would conclude that the npt was designed to produce just the opposite result. Ultimately, however, the credibility of this point will turn on just how economically competitive civilian nuclear projects are when weighed against their alternatives. The U.S. and those other states eager to prevent nuclear proliferation should do all they can to find out.

1 International Panel on Fissile Materials, “Global Fissile Materials Report 2008” (October 2008), available at http://www.ipfmlibrary.org/gfmr08.pdf (these and all subsequent urls accessed May 7, 2009), and Andrei Chang, “China’s Nuclear Warhead Stockpile Rising,” UPIAsia.com (April 5, 2008), available at http://www.upiasia.com/Security/2008/04/05/chinas_nuclear_warhead_stockpile_rising/7074.

2 George Shultz, William Perry, Henry Kissinger, and Sam Nunn, “A World Free of Nuclear Weapons,” Wall Street Journal (January 4, 2007), and George Shultz, et al., “Toward a Nuclear-Free World,” Wall Street Journal (January 15, 2008).

3 If you want to destroy a given fixed target, increasing your aiming accuracy is a much more leveraged way to tackle the task than simply increasing the explosive yield of whatever warhead you might use. Thus, increasing your aiming accuracies ten-fold enables you to increase the probability of destroying the point target as if you had increased the yield of your warhead 1,000-fold and held your aiming accuracies constant. As noted in the text, aiming inaccuracies for missiles have declined not ten-fold, but over 1,000-fold in the past several decades. As a result, the numbers and the average yields of the nuclear weapons in the U.S. arsenal have dropped significantly and non-nuclear warheads have in many instances been substituted for nuclear ones to threaten the same targets. For more on these points see, Lynn Etheridge Davis and Warner R. Schilling, “All You Ever Wanted to Know About mirv and icbm Calculations But Were Not Cleared to Ask,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 17:2 (June 1973); Albert Wohlstetter, “Racing Forward? Or Ambling Back?” Defending America (Basic Books, 1977), reprinted in Robert Zarate and Henry Sokolski, eds., Nuclear Heuristics: Selected Writings of Albert and Roberta Wohlstetter (Strategic Studies Institute, 2009).

4 The Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (npt) actually does not mention any specific nuclear technology or materials that states have a per se right to acquire. On the contentious character of the claim that there is such a right to fuel making, see, inter alia: Victor Gilinsky and William Hoehn, “Nonproliferation Treaty Safeguards and the Spread of Nuclear Technology” (rand, May 1970); Albert J. Wohlstetter, et al., “Moving Toward Life in a Nuclear Armed Crowd?” (acda, December 4, 1975, [revised April 22, 1976]); Wohlstetter, et al., “Towards a New Consensus on Nuclear Technology” (acda, July 6, 1979); Marvin M. Miller, “Are iaea Safeguards on Plutonium Bulk-Handling Facilities Effective?” (Nuclear Control Institute, August 1990); Henry Sokolski, “The Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty and Peaceful Nuclear Energy,” testimony given before the House Committee on International Relations, Subcommittee on International Terrorism and Nonproliferation, March 2, 2006, available at http://www.internationalrelations.house.gov/archives/109/sok030206.pdf; Robert Zarate, “The npt, iaea Safeguards and Peaceful Nuclear Energy: An ‘Inalienable Right,’ but Precisely to What?” in Henry Sokolski, ed., Falling Behind: International Scrutiny of the Peaceful Atom (Strategic Studies Institute, 2008); Christopher Ford, “Nuclear Rights and Wrongs under the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty,” in Henry Sokolski, ed., Expanding Nuclear Power: Weighing the Costs and Risks (U.S. Army War College Strategic Studies Institute, forthcoming).

5 See, e.g., Henry S. Rowen, “This ‘Nuclear-Free’ Plan Would Effect the Opposite,” Wall Street Journal (January 17, 2008). For additional technical background, see David Kay, “Denial and Deception Practices of wmd Proliferators: Iraq and Beyond” in Brad Roberts, ed., Weapons Proliferation in the 1990s, (mit Press, 1995); Victor Gilinsky, et al., “A Fresh Examination f the Proliferation Dangers of Light Water Reactors” (npec, 2004), available at http://www.npec-web.org/Essays/20041022-GilinskyEtAl-lwr.pdf; and Andrew Leask, Russell Leslie, and John Carlson, “Safeguards As a Design Criteria — Guidance for Regulators,” (Australian Safeguards and Non-proliferation Office, September 2004), available at http://www.asno.dfat.gov.au/publications/safeguards_design_criteria.pdf.

6 See, e.g., George Perkovich and James Acton, Abolishing Nuclear Weapons (iiss, 2008), and Henry Sokolski and Gary Schmitt, “Advice for the Nuclear Abolitionists,” Weekly Standard (May 12, 2008), available at http://www.weeklystandard.com/Content/Public/Articles/000/000/015/068ekbiw.asp

7 See, e.g., Kathleen Bailey, The Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty: An Update on the Debate (nipp, March 2001).

8 On these points see Brian G. Chow and Kenneth A. Solomon, “Limiting the spread of Weapon-Usable Fissile Materials” (rand, 1993); Gilinsky, “A Fresh Examination”; “Advice for the Nuclear Abolitionists”; and Christopher Ford, “The United States and the Fissile Material Cutoff Treaty,” (U.S. Department of State, March 17, 2007), available at http://www.state.gov/t/isn/rls/other/81950.htm

9 See, e.g., Robert Einhorn, “Controlling Fissile Materials and Ending Nuclear Testing,” presentation before the International Conference on Nuclear Disarmament, Oslo (February 26–27, 2008), available at http://www.ctbto.org/fileadmin/user_upload/pdf/External_Reports/paper-einhorn.pdf.

10 Christopher Ford, “Five Plus Three: How to Have a Meaningful and Helpful Fissile Material Cutoff Treaty,” Arms Control Today (March 2009), available at http://www.armscontrol.org/act/2009_03/Ford

11 See, e.g., Tim Reid, “President Obama Seeks Russia Deal to Slash Nuclear Weapons,” Times of London (February 4, 2009), available at http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/us_and_americas/article5654836.ece; John Kerry, “America looks to a world free of nuclear weapons,” Financial Times(June 25, 2008); Ivo Daalder and Jan Lodal, “The Logic of Zero: Toward a World Without Nuclear Weapons,” Foreign Affairs (November-December 2008); Sidney D. Drell and James E. Goodby, “What Are Nuclear Weapons For: Recommendations for Restructuring U.S. Strategic Nuclear Forces” (Arms Control Association, April 2005), available at http://www.armscontrol.org/pdf/usnw_2005_Drell-Goodby.pdf; and Graham Allison, Nuclear Terrorism: The Ultimate Preventable Catastrophe(Times Books, 2004).

12 On Russia’s increased interest in using its most advanced bombs for its European defense and as a way to eliminate U.S. electronic battlefield dominance, see Thomas C. Reed and Danny B. Stillman, The Nuclear Express: A Political History of the Bomb and Its Proliferation (Zenith Press, 2009), 198–199.

13 See, e.g., Hugh Gusterson, “The New Nuclear Abolitionists,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (May 13, 2008); Ellen O. Tauscher, “Achieving Nuclear Balance,” Nonproliferation Review14:3 (November 2008); Jeff Zeleny, “Obama to Urge Elimination of Nuclear Weapons,” New York Times (October 2, 2007); and Johan Bergenas, “Beyond unscr1540: the Forging of a wmd Terrorism Treaty,” CNS Feature Stories (October 23, 2008), available at http://cns.miis.edu/stories/

14 Some might rightly point out that the number of deployed nuclear weapons is only one attribute that can be used to describe the effectiveness of a strategic force. A force’s readiness, survivability, accuracy, ability to penetrate defenses, and to hit targets in a timely fashion all go into calculating just how “superior” is one force compared to another. Still, intercontinental ballistic missile-delivered fission warheads used against cities in wealthy states in Europe, Asia, or America might be very potent even if they were militarily crude compared to the most advanced weapons systems. Also, as American and Russian numbers decline and command systems become less vulnerable due to distribution and tunneling, there may well be a shift in targeting policies that might emphasize targeting populations rather than weapons or command centers. If so, relative numbers would constitute a significant metric much as it did in the very early 1950s.

15 International Panel on Fissile Materials, “Global Fissile Materials Report 2008” (October 2008), available at http://www.ipfmlibrary.org/gfmr08.pdf, and “China’s Nuclear Warhead Stockpile Rising.”

16 World Nuclear Association, “Nuclear Power in China” (October 2008), available at http://www.world-nuclear.org/info/inf63.html. China operates a pilot reprocessing plant capable of processing 50 tons of spent fuel annually. There are plans to expand this plant to process 100 tons. This would enable China to make up to 250 crude bombs worth of plutonium a year. China also is planning on completing a large commercial scale plant in 2020 based on indigenous technology located in far western China. Finally, China has contracted with areva to compete a plant by 2025 capable of processing 800 tons of spent fuel annually; the plant will be nearly identical in capacity and design to that which areva helped Japan complete at Rokkasho, i.e., large enough to make between 1,000 and 2,000 bombs per year assuming operation at full capacity and four kilograms of plutonium equating to one bomb’s worth of material.

17 Masafumi Takuba, “Wake Up, Stop Dreaming: Reassessing Japan’s Reprocessing Program,” Nonproliferation Review (March 2008).

18 See, e.g., Zia Mian, A.H. Nayyar, R. Rajaraman, and M.V. Ramana, “Plutonium Production in India and the U.S.-India Nuclear Deal,” in Henry Sokolski, ed., Gauging U.S.-Indian Strategic Cooperation (Strategic Studies Institute, 2007), available at http://www.npec-web.org/Books/20070300-npec-GaugingUS-IndiaStratCoop.pdf, and Zia Mian, A.H. Nayyar, R. Rajaraman, and M.V. Ramana, “Fissile Materials in South Asia” in Henry Sokolski, ed., Pakistan’s Nuclear Future: Worries Beyond War (Strategic Studies Institute, 2008), available at http://www.npec-web.org/Books/20080116-PakistanNuclearFuture.pdf

19 See, e.g., Elaine Sciolino, “Nuclear Aid by Russian to Iranians Suspected,” New York Times(October 10, 2008), and John Larkin and Jay Solomon, “As Ties Between India and Iran Rise, U.S. Grows Edgy,” Wall Street Journal (March 24, 2005).

20 It is worth noting that it took the U.S. only ten months after starting up its first large reactor to test its first bomb — this at a time when it was unclear whether or not the U.S. knew how to make a practical weapon. In the ussr, it took only 14 months. Assuming the reactor in question has been up and running, the distance between decision and detonation could be considerably shorter. On these points, see The Nuclear Express, 83, and Thomas B. Cochran, “Adequacy of iaea’s Safeguards for Achieving Timely Detection,” in Falling Behind.

21 See, e.g., David Kay, “Denial and Deception Practices of wmd Proliferators: Iraq and Beyond,” in Brad Roberts, ed., Weapons Proliferation in the 1990s, (mit Press, 1995); Gilinsky, “A Fresh Examination”; and Mark Clayton, “Will Lasers Brighten Nuclear’s Future: New Process Could Replace Centrifuges But Renew Threat of Nuclear Proliferation,” Christian Science Monitor (August 27, 2008).

22 On this point, see, e.g., Thomas A. Donnelly, “Bad Options: Or How I Stopped Worrying and Learned to Live with Loose Nukes,” in Sokolski, Pakistan’s Nuclear Future.

23 Herman Kahn, Thinking about the Unthinkable (Avon Books, 1964), 222.

24 See the Henry J. Hyde United States-India Peaceful Atomic Energy Cooperation Act of 2006 “Implementation and Compliance Report,” available at http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getdoc.cgi?dbname=109_cong_bills&docid=f:h5682enr.txt.pdf

25 Peter Lavoy, “Islamabad’s Nuclear Posture: Its Premises and Implementation,” in Sokolski, Pakistan’s Nuclear Future.

26 See, e.g., Peter Tynan and John Stephenson, “Nuclear Power in Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Turkey — how cost effective?” (npec, February 9, 2009), available at http://www.npec-web.org/Frameset.asp?PageType=Single& PDFFile=Dalberg-Middle%20East-carbon&PDFFolder=Essays; and Frank von Hippel, “Why Reprocessing Persists in Some Countries and Not in Others: The Costs and Benefits of Reprocessing,” (npec, April 9, 2009), available at http://www.npec-web.org/Frameset.asp?PageType=Single& PDFFile=vonhippel%20-%20TheCostsandBenefits&PDFFolder=Essays.

27 “The Energy Challenge: Energy Review Report2006” (British Department of Trade and Industry, July 11, 2006), available at http://www.dtistats.net/ereview/energy_review_report.pdf.

28 For more on these points, see Henry Sokolski, “Market Fortified Non-proliferation,” in Jeffrey Laurenti and Carl Robichaud, eds., Breaking the Nuclear Impasse (The Century Foundation, 2007), available at http://nationalsecurity.oversight.house.gov/documents/20070627150329.pdf. For more on the current membership and investment and trade principles of theEnergy Charter Treaty and the Global Energy Charter for Sustainable Development go to http://www.encharter.org and http://www.cmdc.net/echarter.html.

29 This set of ideas recently received congressional support from the ranking member of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, the Chairman of the House Subcommittee on Energy and Environment, and the Chairman of the House Subcommittee on Proliferation, Terrorism, and Trade. See the April 6, 2009, letter from Congressmen Brad Sherman, Edward Markey, and Ileana Ros-Lehtinen to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, available at http://bradsherman.house.gov/pdf/NuclearCooperationPresObama040609.pdf. Also, see s1138 Nuclear Safeguards and Supply Act of 2007, available at http://www.govtrack.us/congress/billtext.xpd?bill=s110-1138. Finally, the congressionally appointed bipartisan Commission on the Prevention of Weapons of Mass Destruction Proliferation and Terrorism unanimously recommended that the U.S. discourage the use of financial incentives in the promotion of nuclear energy programs and implement Title v of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Act of 1978. For an explanation of these and the commission’s other key nuclear recommendations, see http://www.npec-web.org/Frameset.asp?PageType=Single& PDFFile=20081200-WmdCommission-AdoptedNpecRecommendations&PDFFolder=Reports.