- Military

- History

- Security & Defense

- Determining America's Role in the World

- Revitalizing History

Americans expect their sons and daughters wounded in battle to receive the most advanced medical care available. Accordingly, military medical professionals now seek to eliminate preventable combat deaths in a bid for battlefield medical supremacy. Yet the expectation of saving every life at any cost must square with the realities of combat. In large-scale conventional wars, overwhelming casualty numbers, contested evacuation routes, and logistics challenges all impinge on the lofty goal of maximizing survival.

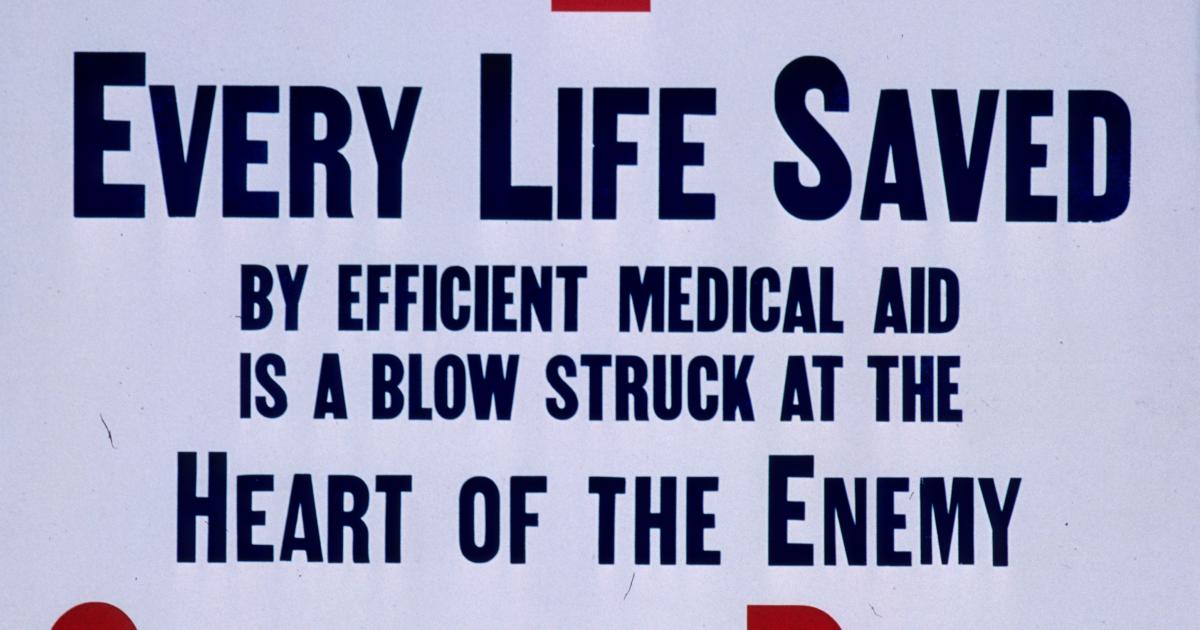

What’s more, our nation often neglects combat readiness between major conflicts. This pattern also extends to medical units at a cost measured in American lives. From the beginning of World War II through the Global War on Terror (GWOT), more than 100,000 combat deaths—roughly one in four—resulted from these lapses in medical readiness. Such preventable deaths not only impede tactical success but also inflict moral injury on the medical teams struggling to save lives. Ukraine reminds us that the scale of any future conflict will dramatically magnify the scale of these needless losses. Such gratuitous deaths violate what the ancient Greeks called θέμις (themis)—our deepest sense of “what is right.”

So how should we approach military medical readiness? Despite our democratic public’s expectations, medical planning to meet the extreme challenges of delivering care in combat often represents a distant afterthought. This haphazard approach need not continue. Rather, we should sustain military medical readiness even during peacetime by training our military medical teams to deliver expert battlefield trauma care on a moment’s notice to better support operational battlefield supremacy.

A Short History of Battlefield Medical Care

Wars inflict pain, suffering, and death. Throughout history, though, commanders and their medics have sought to alleviate suffering and outmaneuver death, albeit with variable success. The Romans crafted the first recognizable system of military medical care among their legions. Soldiers doubling as field medics (capsarii) carried dressing boxes (capsa) and provided initial care for wounded legionaries. Those with severe injuries were evacuated by stretcher or ox cart to hospitals for care by a medicus, an experienced surgeon.

During the Middle Ages, military medical innovation stagnated. Small feudal armies had one or two physicians, but there was no organized system of care during medieval wars. Wounded combatants represented dead weight, typically relegated to the baggage train or killed by the enemy. In 1489, Queen Isabella I of Castile notably objected to this fatalistic approach. Instead, according to Italian scholar Peter Martyr, she provided bedded wagons to evacuate the wounded to hospital tents dubbed Queen’s Hospitals, “not only for the succor and cure of the wounded, but for every imaginable illness.”

Yet this innovation failed to take root over the ensuing three centuries. It was not until the nineteenth century when Baron Dominique Jean Larrey, Napoleon’s Surgeon-in-Chief, was able to transform battlefield care. A revolutionary at heart, Larrey opposed the traditional approaches of leaving the wounded for dead or treating noblemen first and commoners last. He instituted “flying ambulances” on the battlefield, modeled after “light artillery,” to quickly evacuate the wounded to the rear for surgical care. Larrey’s triage—from the French word trier, meaning “to sort”—prioritized severely injured casualties regardless of rank. He was a constant figure on the front lines of Napoleon’s battles, including Waterloo, where his life was spared because of his sterling reputation for attending to friend and foe alike.

Military Medicine on the Modern Battlefield

Over the next century, new weapons delivered increasingly efficient means of destroying life. Machine guns, tanks, and bombs—conventional and nuclear—enabled killing on an industrial scale. As this lethal revolution in the kill chain unfolded, a revolution in the medical survival chain emerged in parallel. Starting with World War I and continuing through World War II, Korea, and Vietnam, military surgeons created and then refined the following formula: staunch extremity hemorrhage, transfuse blood, rapidly evacuate casualties, perform emergency surgery to repair damaged organs, and then provide supportive and restorative care.

During each of these conflicts, medical advances, including those conceived or refined in the thick of combat, complemented this basic framework and steadily improved survival. In Korea, surgeons reconstructed arteries rather than just tying them off (thus saving limbs rather than amputating). Hospital ships provided emergency dialysis to salvage those with kidney failure. In Vietnam, mechanical ventilators delivered pressurized oxygen to casualties with chest injuries and respiratory failure. Combat surgeons pushed the envelope even further during GWOT by using a cutting-edge heart-lung machine for casualty rescue.

Yet, all these advances came in fits and starts. We did not enter each conflict planning to use our most advanced therapies during combat. Instead, we stumbled our way into these solutions, and, at times, failed to deploy them early in the next conflict.

Battlefield Medical Supremacy on Day One

Ensuring optimal emergency and trauma care on day one of the inevitable next conflict requires deliberate planning. The dramatic events during a Monday Night Football game in January 2023 offer a salutary example. Shortly after kickoff, Damar Hamlin of the Buffalo Bills tackled an opponent, popped up to his feet, and then immediately collapsed. NFL medics rushed to his side and found him pulseless. They started CPR, defibrillated his heart, and then rushed him to a nearby medical center where he received expert critical care that restored him to full health. He was discharged a little over a week later and returned to play the next season. The diagnosis: commotio cordis, or sudden cardiac arrest after a blow to the chest. Behind the scenes, the NFL had deliberately trained and equipped their medical teams for this and other life-threatening scenarios. Damar Hamlin is alive today as a result.

What would it take for the U.S. military to deliver similar life-saving care on the first day of a future conflict? First, everyone in the chain of survival must train to the level of trauma expert, according to their station. This starts with the medic on the front lines like the Roman capsarius, continues with the modern-day equivalent of Larrey’s flying ambulances, extends to the surgeon staunching hemorrhage, and ends with all members of the team tasked with ensuring a smooth and complete recovery. Professional societies serve an important role by keeping the lessons of history alive and by supporting training. The Excelsior Surgical Society of the American College of Surgeons has led the way in this regard. Expanding and deepening these linkages to all specialties involved in casualty care and ensuring command support for participation will mitigate the peacetime effect.

We can then build on this baseline of expertise to maintain a strategic advantage over our enemies by continuously pushing the boundaries of battlefield medical care—up to and then even beyond civilian standards. During one of my deployments to Afghanistan, this innovative spirit came to my attention when an enterprising orthopedic surgeon proposed an in-theater MRI. Rather than evacuating every war fighter with a concussion or a sprain, pushing MRI closer to the front lines could clarify the extent of these injuries, allowing some to rehabilitate in place and then safely return to the fight. This kind of “medical overmatch” not only sustains morale and combat readiness but also preserves the fighting force against a determined adversary—all essential to achieving supremacy.

Military medical investments can also pay substantial civilian dividends. Historic examples include blood banks first developed in World War I, industrial-scale production of penicillin in World War II, and trauma systems exemplified in the MASH units of Korea. The war in Ukraine has again exposed the urgent need for this type of innovation: bacteria resistant to most—or even all known antibiotics—routinely infect combat wounds in this theater. For some, fatal sepsis has accomplished what Russian drones could not.

Counting the Cost

Viewed through a weapons systems lens, combat medical care can appear as a costly defensive capability—a tempting target for budget hawks. Wartime medical specialists require years of expensive training. Then, non-competitive salaries and low case volumes in military hospitals lead these specialists to separate at the first opportunity. Beyond attrition, the scarcity of complex, combat-relevant cases directly undermines readiness. One recent study showed only 10% of military general surgeons—considered the anchors of these teams—are combat ready. Finally, military biomedical research also takes a hit during peacetime with predictable cuts to drug development, wound care, and organ replacement programs, despite their life-sustaining dual-use applications. True, a fighting force cannot heal itself to victory, but can we really afford to neglect this capability?

Some argue battlefield medical care interferes with offensive operations. A medic rushing to the side of a casualty—identifying wounds, applying a tourniquet, transfusing blood—loses focus on the enemy. The casualty then requires a ground vehicle, helicopter, train, boat, and/or a fixed-wing aircraft for evacuation. Critics allege such inefficient use of resources ties up crews and congests the battlespace. This argument ignores the morale-boosting effect of these teams and their potential to return some to the fight.

Finally, treacherous enemies view these medical evacuation platforms, their human cargo, and their destinations as high-value targets, despite legal protections. Attacks on non-combatants have occurred in every major conflict since the Geneva Conventions were first ratified in 1864. Even today, Russian forces routinely target Ukrainian medical facilities. Such actions offer a diabolical “triple advantage.” First, striking casualties guarantees they will not return to the fight; second, taking out medical teams eliminates force multipliers; third, attacking medical vehicles and facilities degrades morale among troops and the broader public. Such realities require extreme measures to ensure these teams can perform their life-saving work in relative safety.

Upholding Themis

Why maintain medical continuity between conflicts, sustain a pipeline of combat medical experts, commission research to improve battlefield survival, deliver expensive medical equipment to the front lines, and put lives at risk to save another? In a word, themis. With sufficient planning enabled by well-crafted polices stiffened by political will, these challenges can be met at a scale required to face even a peer enemy. Military trauma teams can train in civilian trauma centers. Reserve and guard units can mitigate recruitment and retention shortfalls. Combat-relevant biomedical research can advance, if adequately funded. Deployed medical teams can be shielded from attack. In return, planning for and implementing battlefield medical overmatch builds confidence among our warfighters and optimizes their combat effectiveness. This ethos—regarding every life hanging in the balance as worthy of our maximal effort—leverages the intrinsic military advantage afforded by our democratic values.

The debate over acceptable operational risks versus the benefits of exerting battlefield medical supremacy erupted during the Afghanistan surge between then Secretary of Defense Robert Gates and his commanders. For years, the military had maintained a “golden hour” medical evacuation standard in Iraq but not Afghanistan. When Secretary Gates challenged this discrepancy, he met significant resistance. Operational leaders cited increased workload and operational risk for little benefit. Gates ultimately appealed to themis and mandated a one-hour limit from evacuation request to surgical care. “[It] was about the troops’ expectation and their morale,” he later reflected, “and by God, we were going to fix it.” This bold decision saved hundreds of American lives.

As the father of a service member, I now have a new perspective beyond my sense of duty as a military surgeon. My family, including my son, accepts that he might suffer terrible wounds or even die in the line of duty. However, we refuse to accept, and I contend no American family should accept, that this could happen at the hands of an apathetic system. Establishing battlefield medical supremacy from the outset of our next conflict represents a new but achievable paradigm. The American public must simply demand it.