- Economics

- Budget & Spending

In the midst of the Vietnam War, when 550,000 military personnel were deployed there, Congress members noted another issue that was generating more constituent mail than the war. A 1969 Treasury Department report stated that 155 individuals with adjusted gross incomes of more than $200,000 paid no federal income tax in 1966. The average American was outraged and wrote to Washington about it.

Congress responded quickly and enacted an “additional tax for tax preferences”—the precursor to today’s alternative minimum tax (AMT). This legislation created a minimum tax provision in the IRS code intended to prevent high-income earners from using tax breaks to escape all federal income taxes.

The AMT was meant to snare the rich, and the effects were immediate. In 1969, the year before the minimum-tax laws went into effect, 300 people who earned more than $200,000 owed zero federal income tax. This was 1.6 percent of those in the $200,000-plus adjusted gross income (AGI) bracket. In 1970, only 111 people (0.7 percent of the $200,000-plus bracket) avoided paying federal income tax, a substantial decline both in hard numbers and in percentages.

The AMT remains effective today, ensuring that few high-income earners avoid paying income taxes. In 2004, 177 returns with AGIs above $1 million (approximately what $200,000 in 1969 is worth in today’s dollars) did not owe any taxes. This is only 0.1 percent of those in that high-income category. It has gotten pretty hard to avoid paying any federal income tax.

However, the AMT legislation did not index for inflation. Bracket creep (when individuals move to higher tax brackets because of inflation, not because of increases in real income) was essentially eliminated from the tax code in the 1980s, but bracket creep is alive and well today in the AMT.

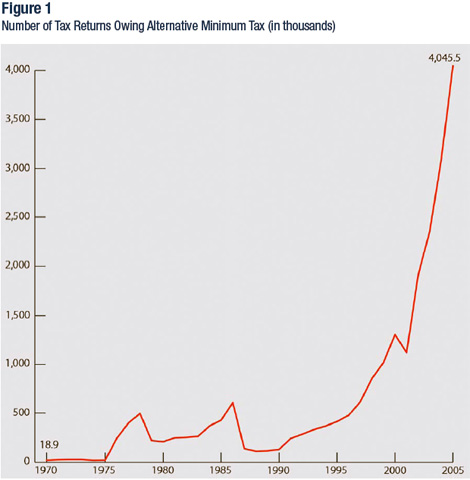

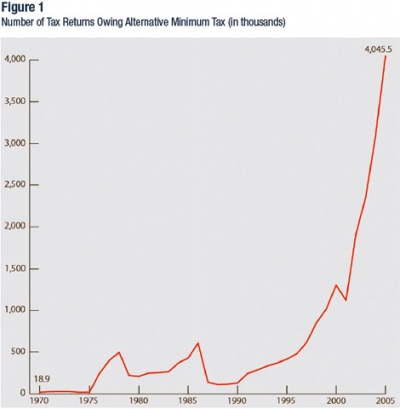

In 1970, some 19,000 people (0.03 percent of the tax-paying population) paid the AMT equivalent. By 2005, this number had risen to more than 4 million (4.5 percent of the tax-paying population). By either measure, more than 150 times as many people paid the AMT in 2005 as did in 1970.

Although originally targeting the very wealthy, the AMT has increasingly shifted toward those in the middle-class and upper-middle-class income brackets. In 2005 (the last year for which detailed data are available), one in twelve subject to the AMT had AGIs of less than $100,000. In total, 45 percent of those paying the AMT had AGIs of less than $200,000—not the destitute, but certainly not the super rich Congress was focused on in 1969. Little did those who wrote to Congress in 1969 know that their letters would lead to legislation that could easily end up ensnaring them.

There are also distorting geographic effects. The AMT works primarily by limiting the extent to which deductions may be taken—notably mortgage interest, property taxes, and state income taxes. Hence, the AMT disproportionately affects those from the East Coast and California, where housing prices (and mortgage interest payments) and state and local taxes are higher.

Sound public policy must be transparent, sensible, widely known, and generally approved of. The AMT is none of these. It is expected that the AMT will snare about 25 million taxpayers this year. In most cases, those unsuspecting taxpayers will have little previous knowledge of this tax and most certainly will disapprove of this parallel tax system that is imposing an unexpected burden of $6,800 per payer, not including compliance costs. For them, the Bush tax cuts are proving to be far less than what they expected.

Currently, the chairman of the United States House Ways and Means Committee, Charles Rangel is attempting to pass a temporary patch to the AMT that would shield the 25 million people from this tax for the 2007 tax year. Rangel is also looking at longer-term overhauls that may repeal this tax, but it is not expected to move through Congress until next year. The patch is certainly a good start. However, with the November 1 deadline for the IRS to modify 2007 tax forms looming, Congress needs to act swiftly and decisively.

The patch is a step in the right direction to help return the AMT to its original intent of making sure the wealthy pay their taxes, rather than serving as an ATM for the government.