- Middle East

- Military

- Determining America's Role in the World

There is nothing more dangerous for the state than men who want to govern kingdoms on the basis of maxims which they cull from books. When they do this, they often destroy them, because the past is not the same as the present, and times, places, and persons change.

Cardinal Richelieu

Introduction

There is an old naval saying, often misattributed to British Admiral Horatio Nelson, that “a ship’s a fool to fight a fort.” Driven by both modern weaponry improvements and recent operational experience in and around both the Red and the Black Sea, Nelson’s adage, as Cardinal Richelieu suggests, appears long overdue for an update.

Throughout history, the sea has been the domain of naval power, serving as the critical artery for trade, projection of power, and strategic influence. From the triremes of ancient Greece to the aircraft carriers of the 20th century, maritime dominance has traditionally rested with naval forces. However, the 21st century has seen a marked shift in this paradigm. Advances in technology, the proliferation of anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) systems, and evolving strategic doctrines have enabled land forces to exert a disproportionate influence over maritime spaces. By leveraging long-range missile systems, sophisticated sensor networks, and integrated command structures, land-based forces are now capable of effectively contesting, and in some cases, denying access to both maritime commerce and naval forces in critical maritime regions.

The global economy is deeply dependent on maritime commerce, which remains the primary mode of transporting goods between continents. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), over 80% of global trade by volume and more than 70% by value is carried by sea. The efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and capacity of maritime shipping make it irreplaceable, especially for bulk commodities like oil, natural gas, grain, and industrial raw materials, as well as manufactured goods and containerized cargo.

Despite the resilience of maritime trade, the dependence on a limited number of critical chokepoints introduces significant strategic vulnerabilities. These narrow straits, canals, and passages are often within reach of land-based area denial systems, making them attractive targets for adversaries seeking to disrupt global supply chains or exert geopolitical influence.

Key chokepoints

- The Strait of Hormuz through which transits over 20 million barrels of oil per day. It is vulnerable to Iranian land-based anti-ship missile batteries, fast attack craft, naval mines, and drones. Past incidents, such as the “Tanker War” during the Iran-Iraq conflict and recent Iranian actions, illustrate its vulnerability.

- The Strait of Malacca which sees approximately 100,000 vessels transit annually, carrying about 30% of global trade by volume. Though historically peaceful, transiting shipping is within easy range of simple area kinetic capabilities. Threats here include piracy, terrorism, and potential state-level interdiction during crises.

- The Suez Canal and Panama Canal are critical artificial waterways connecting major oceans and are the subject of recent geopolitical debate. Though heavily secured, blockages or sabotage (e.g., the Ever Given incident in 2021 in which a ship became wedged in the Suez Canal) can have disproportionate global economic impacts. Additionally, historically low water levels in the Panama Canal reduced traffic by 36% year-over-year.

- The Turkish Straits (Bosporus and Dardanelles) are critical for both Ukrainian and Russian oil, gas, and grain exports. They are controlled by Turkey under the Montreux Convention, giving Turkey significant leverage in times of conflict.

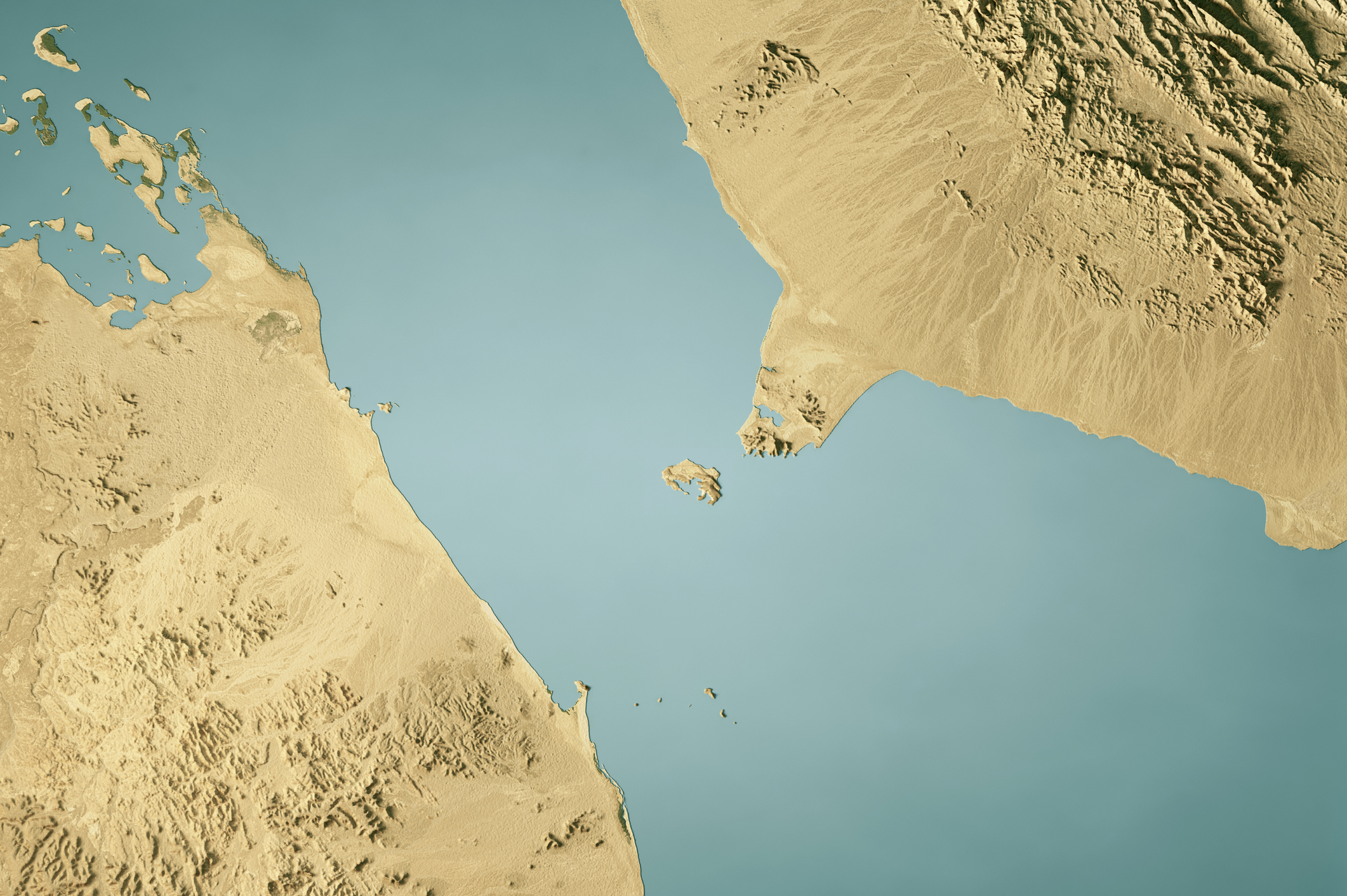

- The Bab-el-Mandeb Strait is a key link between the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden through which historically over 9% of global seaborne oil trade passes. As recent events have shown, the Strait is vulnerable to Houthi rebel attacks, including anti-ship missiles, drones, and naval mines. Geopolitical tensions and security concerns have significantly impacted oil shipping through the strait. According to Vortexa data, oil trade through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait plummeted to an average of 4.0 million b/d in 2024, a stark contrast to the 8.7 million b/d recorded in 2023. This decline is attributed to increased attacks on commercial shipping in the Red Sea, particularly by Yemen’s Houthi rebels. These attacks have led major shipping companies to reroute their vessels around the Cape of Good Hope, increasing transit times and costs.

Background

While the concept of using land forces to influence the sea is not entirely new—coastal artillery and fortifications have long served this purpose—the modern iteration of area denial is more dynamic and far-reaching. The Cold War era witnessed the Soviet Union developing layered defensive networks along its coasts, deploying shore-based missile batteries, submarines, and air defenses to contest NATO maritime forces. However, these efforts were largely defensive, aimed at protecting Soviet shores and fleet bastions.

The post-Cold War period, with the emergence and proliferation of precision-guided munitions, network-centric warfare, and the digitization of the battlefield, has dramatically expanded the reach and effectiveness of land-based systems. The concept of A2/AD has evolved from static coastal defense to dynamic, multi-domain operations capable of projecting influence hundreds or even thousands of kilometers from shore. Land forces are now able to create overlapping “kill zones” in critical maritime chokepoints and littoral regions, challenging traditional notions of sea control and maritime superiority.

The People’s Republic of China is employing a multi-faceted A2/AD strategy to exclude or deter as many adversary forces from acting within the waters it claims as its territorial waters as outlined by the so-called 9 dash line. The initial impulse for this strategy is said to have been the deployment of two US aircraft carrier battle groups in the area, led by this author and reacting to Chinese tests and exercises for a possible invasion of Taiwan in 1996, which went effectively uncontested by the Chinese navy. The Chinese A2/AD strategy's main focus lies on sea denial by land and ship-based missiles but features submarines and tactical aircraft as well.

The major change to the historic contest between major maritime and land powers is the proliferation of modern capabilities to small or even non-state actors. The democratization of maritime control has fundamentally altered the traditional balance of sea power. Land powers, insurgent groups, and regional players can now exert significant control over chokepoints without needing dominant naval forces, complicating maritime strategy for global powers, increasing the strategic volatility of these regions, and allowing them, in the case of commercial shipping, to hold global commerce hostage.

These efforts, especially by non-state actors, can create proxy conflicts that can serve the strategic interests of nation-states while still affording them plausible deniability. That is certainly true in the case of Iranian support to the Houthis, where recent weapon shipment interdictions, in addition to classified intelligence, show a clear linkage to Iran. Interestingly, recent public reports of Chinese commercial satellite companies providing targeting imagery to the Houthis has led to speculation that the rebels have agreed not to target Chinese ships in return.

Should maritime confrontations begin to move up the spectrum to potential major-power conflict, their war insurance will immediately become void. Current maritime insurance policies include the Five Party War Clause which addresses in-place war risk insurance and, per the American Institute of Maritime Underwriters’ wording, “excludes loss, damage, liability, or expense arising from the outbreak of war (whether there be a declaration of war or not) between any of the following: United States of America, United Kingdom, France, the Russian Federation, the People's Republic of China.” It is important to note that, even after a small number of successful attacks, just the threat of subsequent attempts is often enough to drive commercial shipping insurance rates significantly higher. This can lead shippers to voluntarily divert their vessels around the troubled waters, adding, in the case of Red Sea traffic, two weeks to their voyages and forcing major adjustments to last minute logistics planning.

The ascendancy of land-based maritime area denial capabilities presents significant challenges to traditional naval power projection concepts. Carrier strike groups, amphibious ready groups, and logistics convoys operating within the range of advanced A2/AD systems are increasingly vulnerable, necessitating adaptations in naval doctrine, force structure, and operational planning.

Redefining Sea Control and Power Projection

The ability of land forces to contest naval operations in littoral and even open ocean areas challenges the assumption of uncontested sea control. Naval forces steaming alone or in escort of commercial shipping must now operate under the constant threat of land-based precision strikes, requiring the adoption of distributed lethality, increased use of unmanned platforms, and the development of counter-A2/AD capabilities.

Integration of Multi-Domain Operations

Preserving future maritime security and unrestricted access will require integrated multi-domain operations, where land, air, sea, cyber, and space forces work cohesively to counter area denial threats. This includes the use of long-range fires from naval platforms against land-based A2/AD assets, the employment of cyber operations to degrade enemy sensor networks, and the leveraging of space-based assets for enhanced situational awareness. Quickness and agility will be required. The new land forces are no longer a “fort” in the classic sense, fixed and immobile, perched on a hill and crouching behind massive stone walls. Rather the “fort” is geographically dispersed, highly mobile, disguised as commercial trucks ashore or fishing vessels if at sea.

Shifts in Strategic Posture and Defense Investments

All nations are now facing the threat of cheap, mobile, and effective land-based A2/AD threats. While they may need to invest more heavily in capabilities such as hypersonic weapons, electronic warfare, and missile defense systems to restore freedom of maneuver in contested maritime spaces, the economics of using multimillion dollar missiles to counter potentially hundreds of hostile weapons that are an order of magnitude cheaper, highly mobile, and much more quickly resupplied is unsustainable over the long term. Additionally, the continued proliferation of A2/AD capabilities among non-peer competitors will democratize the ability to contest maritime domains, leading to a much more complex and contested global maritime environment.

Conclusion

The modern trend of land forces asserting dominance over the maritime domain through area denial strategies represents a significant evolution in the character of warfare. Enabled by technological advancements and driven by strategic imperatives, land-based A2/AD systems have reshaped the balance of power in critical maritime regions, challenging the primacy of naval forces and altering the dynamics of future conflicts.

For naval powers, adapting to this new reality will require innovative approaches, investment in new capabilities, and a willingness to embrace multi-domain operations. For land powers, the ability to influence the sea from the shore provides a potent tool of deterrence and coercion, reinforcing their strategic objectives without the need to field large navies. As the maritime domain becomes increasingly contested from the land, the future of naval warfare will likely be defined not only by the ships that sail the seas but also by the missiles, sensors, and systems deployed on the shores that overlook them.

A final thought

In addition to modifying the opening quote to reflect the challenges of ships fighting a missile, drone, and mine-defended coasts, it is also appropriate to remember that a more final conclusion to shore-based maritime challenges can require another dimension of maritime power. To bring to an end the decades long war between the nascent America and the Barbary pirates required the employment of land forces originating from the sea. A small contingent of naval infantry and a sizeable mercenary force was inserted to capture the enemy’s capitol and compel capitulation, as memorialized in the second line of the Marine Corps Hymn: “from the shores of Tripoli.”