- World

- Contemporary

- Security & Defense

- Terrorism

- History

October 9, 1967, was the luckiest day of Che Guevara’s life. That’s when he was captured, with CIA assistance, in the Bolivian highlands, was killed, and became immortal. In one day, he was martyred and raised in glory from the dead.

If Ernesto “Che” Guevara were alive today, like doddering Fidel Castro, he would be eighty years old, and the by-now gray or bald perpetual loser might have chalked up such a string of failures that no matter how hard Castro and others tried, they could not have created the pervasive cult of Che. But dying so dramatically so long ago froze him in time, and like the youngsters on Keats’s Grecian urn, Che will remain “forever panting, and forever young.” He is fodder for the propaganda apparatus of Che’s equally fraudulent “successor,” Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez, the latest of Latin America’s false messiahs.

Today, Che has come to mean many things to many people, across all generations and around the world. A church recruiting poster shows a pastiche of Che and a baby challenging people to decide whether Baby Jesus was really a revolutionary. Che is a romantic figure to some young and notso- young women. He can be a defiant “middle finger” image challenging authority, useful to, for example, the Hong Kong democratic politician who wears a Che T-shirt to stick it to Beijing, or to American kids rebelling against parents and teachers. For others he is simply “radical chic,” as Tom Wolfe labeled the phenomenon back in the days of Leonard Bernstein’s celebrated mingling with the Black Panthers.

You might find Che anywhere—even in Assisi, Italy, where Saint Francis souvenirs are sold as cynically as Che T-shirts.

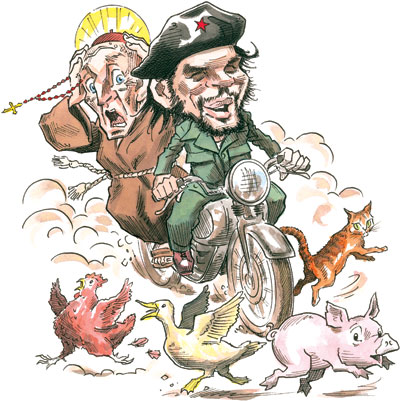

For others, he is a cash cow, having been transformed “from communist firebrand to capitalist brand,” as Alvaro Vargas Llosa argued in The Che Guevara Myth and the Future of Liberty. Of course, anything animal, vegetable, or mineral that can be exploited for bucks will be; in this spirit, Che is fair game. Already, the wandering route to his death has become an adventure trail for tourists, like the Chu Chi guerrilla tunnels in Saigon and Cultural Revolution Tea Houses in China. By the same token, in Assisi, Italy, Saint Francis is sold as cynically as Che is in Cuba. (And, yes, Che Tshirts are available in Assisi, too, next to statuettes of Saint Francis and his animals.) Last year in Prague, a huge man wearing a sandwich board cut me off near the Charles Bridge to peddle a “Che breakfast.” Che relics also sell: some 100 strands of his hair, cut from his corpse, were recently bought by a Texas bookstore owner for $100,000. One wonders how soon the pilgrimages will begin.

But Che also has admirers or manipulators who need to be taken more seriously than the hucksters. Those followers are playing with political fire and could in some ways affect the future. Che was a hard-driven, messianic character operating in a culture that has long urged people to line up behind paternalistic leaders who promise to redeem the downtrodden by crushing centuries-old tyrannies. He lived and died in a culture enamored of martyrs. No wonder Venezuelan President Chávez and populist “Chavistas” in Bolivia, Ecuador, and other nations consider Che a revolutionary icon useful for their own purposes.

WHO WAS HE?

Che was a well-educated, middle-class Argentine-born Basque with Irish links. He was athletic but suffered from periodic, crippling bouts of asthma. The part of his life that concerns us began when he traveled the length of South America in the 1950s, a trip popularized in the 2004 film The Motorcycle Diaries, produced and championed by Robert Redford. On that trip, Che learned firsthand about a continent plagued by what Moises Naim calls “legendary malignancies: inequality and poverty, dysfunctional politics and malfunctioning institutions.” The experience contributed much toward his becoming a zealous advocate and practitioner of salvation for the downtrodden poor through revolutionary warfare, on his own terms. Widespread admiration for the young man of the Diaries days—without consideration of what he did later—led Paul Berman to remark that the flowering of the Che cult reflects “the moral callousness of our time.”

Guerrilla warfare was very much in vogue in Latin America before 1967 (and a bit thereafter), when Che died. The guerrillas’ declared enemies were domestic governments, military and democratic, and the United States— though they often fought more with each other than their declared enemies, behaving like the “liberation fronts” in the stadium in the Monty Python film Life of Brian. Latin America was then passing through one of its periodic spasms of intense anti-Americanism.

Che was a hard-driven, messianic character in a culture that has long urged people to line up behind paternalistic leaders who promise to redeem the downtrodden.

Che’s image rose above all others for several reasons. He had helped Castro seize power in Cuba, and thus had been part of the only successful revolutionary victory of any consequence in Latin America during those years. Also, he wrote several short books about guerrilla warfare that circulated widely, from the Americas to China and Vietnam. Castro had insisted that “it is the duty of every revolutionary to make the revolution,” and in his books Che tried to tell would-be guerrillas how it was done. And Che was handsome, quietly dramatic, macho, and photogenic in a rough sort of way. His image benefited much from the popular photos by Alberto Korda, particularly the one with the halo. Moreover, he was martyred by the Americans or their allies.

In real life, Che failed in almost everything he did. He held several government positions in Cuba between 1959 and the mid-1960s: he was a brutal executioner of anti-Castro Cubans in La Cabaña prison and an incompetent head of the national bank and minister of industry. In the mid- 1960s, he realized he was a hopeless administrator, and as competition with Castro became a problem he retreated to the one thing for which he was internationally recognized: fomenting and waging guerrilla warfare. But again, he was an abject failure, first in Africa and finally in Bolivia, where he never got one peasant to join his war “on their behalf ” and was tracked down, with peasant help, no less, and killed along with many others.

Che was obsessed by the U.S. involvement in Vietnam, a concern that resonates today as a new generation of critics, both left and right, have turned against U.S. policy in Iraq and possible future interventions from Iran to Cuba. Che was apocalyptic in his last major speech/article, the 1967 “Message to the Tricontinental,” a group of Third World revolutionaries based in Cuba. He eagerly looked forward to “two, three, many Vietnams” around the world, which would overextend the United States and precipitate its collapse. The 1966–67 war in Bolivia, where Che died, was intended precisely to create “a Vietnam in the Americas with its heart in Bolivia,” as his Cuban comrade Pombo (Harry Villegas) wrote in his diary. Che’s final writings promote a cultivation of the “unbending hatred” necessary to turn people into “an effective, violent, selective, and cold-blooded killing machine.” Only when this happens worldwide, he believed, would domestic and foreign exploiters be defeated.

A TWISTING HIGHWAY

Like his motorcycle odyssey, Che’s road to universal iconhood has taken some odd turns. In September 2007, Che’s virulent anti-Americanism led militant students at Tehran University to invite two of his children to a conference intended to link Iran’s Islamist revolution to the socialist revolution in Latin America. (Hugo Chávez is seeking to do the same by carefully cultivating ties to Iran and President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.) An Iranian supporter of suicide bombings at the conference declared that communism is defunct and that Che believed in God, so the Argentine-Irish-Cuban would certainly have agreed that the only route to liberation today is “the religious, pro-justice movement.” But Che’s daughter Aleida countered that her father believed in socialism, not God. “My father never talked about God,” she said. “He never met God.” She and her brother, Camilo, were quickly packed up and shipped back to Cuba.

On more familiar turf, such as Cuba, Che’s admirers argue that he was a selfless defender of the downtrodden poor against predatory domestic and foreign oppressors. At a fortieth-anniversary memorial service in Bolivia, President Evo Morales said people today can’t even try to be successors to Che unless they are ready to “give their life for humanity.” Chávez has just announced a new program in Venezuela called the “Mission Che Guevara,” which is intended to integrate Che’s “socialist values” into all aspects of national development. And Cuban schoolchildren have long been taught to chant “We will be like Che!” meaning they will work and die selflessly for the revolution, as Che presumably did.

That vision of Che is gaining some currency again because most Latin American governments are making slow progress, if any, in improving the lives of most of their people, and anti-Americanism is again on the rise. Che is extolled as one who was willing to give everything, including his life, to eliminate injustice, in contrast to current leaders who bleed the system to benefit themselves and their cronies.

In October 2006, Cuba claimed that eye surgery by Cuban doctors had restored the sight of Che’s executioner, Mario Terán. The moral, said the Communist Party paper Granma, is that four decades after Terán had “attempted to destroy a dream and an idea, Che returned to win yet another battle.” Parts of the Che hagiography—from Tehran to Terán—are becoming as surrealistic as Mao Zedong’s Little Red Book. What does Che really mean, beyond the oratory and the T-shirts?

THE END OF THE ROAD

Che’s life is more than the sum of his defiant public statements; we must also reckon with the consequences of his actions. In the end, his legacy is precisely the opposite of what ignorant and self-interested parties claim it to be. Che may have meant what he pledged, but his campaigns to liberate the poor failed to empower any class of society in Latin America—except, for a while, the military forces that surged while crushing guerrilla uprisings.

Spain’s foremost leftist paper, El País, summarized Che’s achievements well when it editorialized in October that Che’s sacrificing his own and many other lives doesn’t make his ideas any better than the totalitarian models from which they were drawn. (When Che visited Pyongyang in late 1964, he proclaimed North Korea the model Cuba should follow.) The paper correctly concluded that “his projects and slogans left nothing but a trail of failure and death, both in Castro’s Cuba, the only place they triumphed, and in places from the Congo to Bolivia where they did not attain victory.”

Perhaps his anti-imperialism alone made Che an everlasting hero, as some of his admirers believe, though anti-Americanism, then as now, was as common as asparagus in May. Whatever his objectives might have been, Che promoted conflict that led to many thousands of deaths in guerrilla wars against democratic as well as authoritarian governments in the Americas. Had he succeeded in creating the “two, three, many Vietnams” he so fervently sought, he would have brought incalculable death and destruction on people worldwide. Today, there is no great public sympathy in most places for turning people into “cold-blooded killing machines” to wage multiple Vietnam Wars around the globe.

Che was “selfless” in his commitment, but he nurtured a stubborn belief that he had all the answers, which enabled him to mercilessly exploit others in pursuit of his ends and to visit enormous damage on all who crossed his path or the paths of those influenced by him.

In some respects, the Americas are still recovering from the actions of Che and others like him. As Mexican analyst and former foreign minister Jorge Castañeda noted in a recent commentary, Che’s guerrilla uprisings, the false hopes they preached, and the repression they precipitated postponed the coming of age of leftist and rightist political parties in Latin America and the development of more representative political systems. The time it took to reach equilibrium delayed development in much of the region. In recent years, modestly reforming parties of the right and left have been voted into power in many countries, but even their best efforts are now challenged by a new round of purported miracle workers, the Chavista populists who use Che’s aura to support their actions. The result is yet another postponement of the reforms that will benefit the majority of Latin America’s people. In Cuba, the efforts of Che and Castro to create the “new man” have been absolute failures because they are contrary to human nature, and because they guarantee the continuation of the economic and political paralysis that still cripples the island after almost a half century. Even in Vietnam, much lauded by Che and Fidel, communist victory after prolonged warfare brought no real improvements in the living standards of the people until market-oriented reforms began in 1986.

Che may have meant what he pledged, but his campaigns to liberate the poor failed to empower any class of society in Latin America—except, for a while, the armies that crushed guerrilla uprisings.

And now? The good news is that much Che worship is simply frivolous and mercenary, even among American and European intellectuals, where adulation of shallow revolutionaries is a long-standing habit. As the El País editorial demonstrated, an increasing number of those leftists are coming to recognize Che as a bumbling disaster. But some hesitate to apply the real lessons of Che’s life and myth, for they support Che’s successor, the twenty-firstcentury Chávez with his “twenty-first-century socialism,” the same fraudulent miracle in new clothing. This is the threat that the cult of Che poses today: the perpetuation of the myth of worldly salvation by a caudillo messiah. The best we can hope for at the moment is that Ernesto “Che” Guevara will be recognized for what he really was: the Patron Saint of War, False Causes, and Failure. Hugo Chávez will inherit those titles in time, but not before the Americas pass through another painful and pointless trial by fraud.

Special to the Hoover Digest.