- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- Budget & Spending

- Economics

In December 2010, President Obama and Congress reached an agreement whereby the Social Security payroll tax would be cut by two percentage points in 2011—from 12.4 percent to 10.4 percent—as a temporary stimulus measure. The president later proposed that the cut be extended and expanded in 2012. Before Congress went home at the end of 2011, it passed a 60-day extension of the two-point tax cut. The payroll tax cut has now been further extended to last throughout 2012 at least.

Most public discussion of the payroll tax cut has pertained to its efficacy (or lack thereof) as economic stimulus. Its greater policy significance, however, lies in another provision tucked into the same law. This provision is now transferring more than $215 billion in general tax revenues (e.g., income taxes) into the Social Security Trust Fund to make up for the reduction in payroll tax revenue.

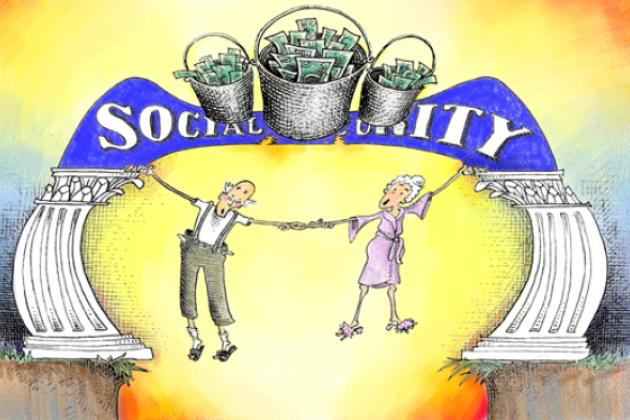

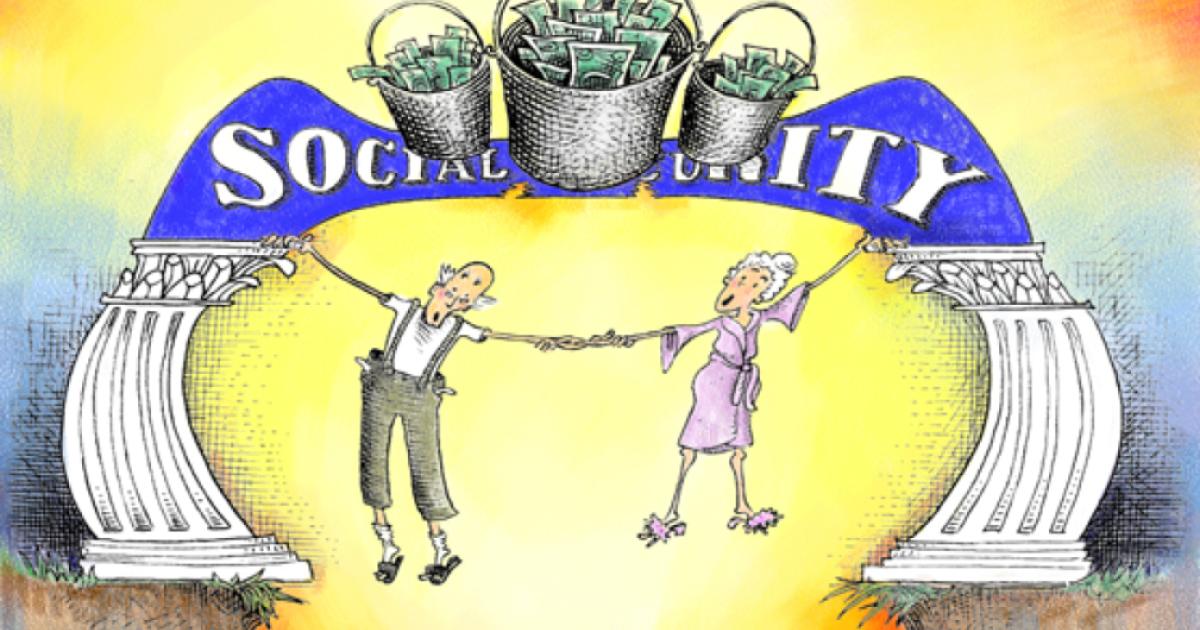

Illustration by Barbara Kelley

In other words, the payroll tax cut is not really reducing the amount of tax revenues committed to Social Security. All that it actually does is to shift the Social Security financing burden from covered workers to others—most notably, to those Americans who pay income taxes. This is a transformative change to Social Security, reflecting goals for broader income redistribution now ascendant on the left end of the American political spectrum.

Social Security, as originally envisioned and implemented by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, has historically been financed through a separate payroll tax levied on covered workers. Its finances have been tracked through a separate Trust Fund system, distinct from the general federal budget. This financing method reflects a foundational principle of the program, distinguishing it from welfare. Under a welfare program, by contrast, benefits are based on need while revenue contributions are based on one’s ability to pay. Social Security was instead designed such that all workers—rich and poor—would pay payroll taxes. Benefits in turn were to be based on the amount of an individual’s wages subject to this tax. A higher-wage worker would thus pay more in taxes but also receive more in benefits.

This arrangement represented a politically stabilizing compromise between the left and the right. The right was to be assured that Social Security costs would not, at least in the aggregate, exceed the revenues the program generated. The left received an additional political protection for benefits, arising from the popular perception that beneficiaries had paid for them.

Now that Social Security has begun to be subsidized directly with income taxes, neither of these assurances can continue. The new policy ends the longstanding requirement that Social Security expenditures be limited to the total amount of its tax collections (plus interest). And, by subsidizing payments with income taxes, it ends the idea that the Social Security benefits are fully “earned” by recipients.

What led to this momentous change? The answer: a change of heart about Social Security policy among influential left-of-center policy advocates over the last decade.

Historically, Social Security contributions and benefits have been linked.

For most of Social Security’s history, the American political left had seen the program’s self-financing construct as the essential foundation of its political support. They recognized this as the reason Social Security escaped the calls for benefit cuts directed at traditional welfare programs, even well after its costs had far exceeded the others’. President Clinton’s 1994-96 Advisory Council, for example, unanimously opined that “Social Security should be financed . . . without other payments from the general revenue of the Treasury.” As the Council stated, “The fiscal discipline in Social Security arises from the need to ensure that income earmarked for Social Security is sufficient to meet the entire cost of the program . . . rather than from competition with other programs in the general budget.”

In recent years, however, the left’s commitment to this principle has eroded. As their stated concerns about general income inequality grew, there came a proliferation of proposals to replace Social Security’s “regressive” payroll tax financing with income generated from progressive income taxes. The partial conversion last year of Social Security to income-tax financing represents the first concrete step in executing this change.

For clarity, it should be noted that it is incorrect to view the Social Security payroll tax as “regressive.” The payroll tax can be thought of in one of two self-consistent ways—either as:

1) establishing an entitlement to Social Security benefits, or;

2) as part of the general burden of financing government.

If the payroll tax creates a genuine entitlement to Social Security benefits, then it is clearly not regressive. Payroll tax dollars paid by lower-wage workers accrue benefits at a substantially higher rate than those paid by higher-wage workers.

The other way to look at the payroll tax is to think of it not in terms of the Social Security benefits it earns, but as part of the tax burden of financing the federal government as a whole. But this view, too, leads to the conclusion that the tax system is progressive. The Congressional Budget Office has repeatedly documented that total tax burdens (including payroll tax burdens) are proportionally far higher for higher-income Americans.

Social Security’s payroll tax only appears to be “regressive” if one conducts a one-sided evaluation: that is, treating the tax—but not the benefits that it buys—as separable from general government finances. Nevertheless, the idea has taken root with some that not only should Social Security’s benefit formula be highly progressive, its revenue sources should also be progressive—even if this means eradicating the program’s historical connection between contributions and benefits.

The first milestone in this policy journey was President Clinton’s 1999 proposal to transfer general income tax revenues to the Social Security Trust Fund. As GAO Comptroller General David Walker then stated, “This proposal represents a fundamental shift in the way the Social Security program is financed. It moves away from payroll tax financing toward a formal commitment of future general fund resources for the program. This is unprecedented.” President Clinton’s idea was intensely controversial at the time and was never, unlike President Obama’s, taken up seriously by the Congress.

The idea that higher-income Americans should begin to subsidize Social Security—and, for the first time, receive no benefits for those added contributions—gained significant momentum among left-of-center policy advocates in the decade after President Clinton first proposed it. Noted economists Peter Diamond and Peter Orszag proposed in 2003 that a Social Security “legacy tax” be imposed “on earnings above the taxable wage base, thereby ensuring that very high earners contribute to financing the legacy debt in proportion to their full earnings.” No benefit credits were to be allocated based on this additional 3 percent “legacy tax.”

We need to reallocate resources between generations, not income classes.

The “legacy debt” concept espoused by Diamond and Orszag attributed the Social Security shortfall in part to the fact that the “benefits paid to almost all current and past cohorts of beneficiaries exceeded what could have been financed with the revenue they contributed, plus interest.” Other advocates took up this theme in arguing that progressively assessed tax contributions should be tapped to bail out Social Security. In “The Social Security Fix-It Book” published by the Center for Retirement Research, for example, a similar option was described to “transfer these start-up costs to general revenues.”

The “legacy tax” concept is essentially a rationale for breaking Social Security’s contribution-benefit link by requiring upper-income taxpayers to contribute additional subsidies. Certain specific aspects of that rationale, however, are problematic:

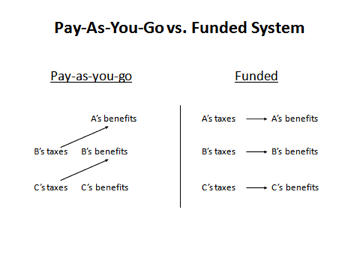

1) It is based on a misdiagnosis. Although it is true that Social Security’s first beneficiaries received benefits far beyond what they put in, this is not the cause of Social Security’s projected shortfall. The so-called “legacy debt” is actually just a manifestation of “pay-as-you-go” financing, in which each generation pays for the benefits of the previous one. The graphic below depicts alternative financing methods affecting hypothetical generations A, B and C.

A pay-as-you-go system can actually remain financially stable providing that its ratio of contributing workers to collecting beneficiaries remains constant, and that its tax and benefit formulas are appropriately balanced. Indeed, Social Security would be in financial balance today if two critical factors were different than they are: if the population were not aging, and if substantial benefit expansions had not been enacted in the 1970s.

Indeed, the so-called “legacy debt” of Social Security will always be a historical reality—even after legislation is enacted to eliminate the program’s financing shortfall. By definition, therefore, what must be done to address Social Security’s shortfall has nothing to do with erasing its “legacy debt.”

2) The proposed solution of taxing higher-income earners is unresponsive to the phenomenon described. The so-called “legacy debt” is a description of a reality in which earlier generations under Social Security received a windfall paid for by later generations. The so-called “legacy tax,” however, does not address this; instead of shifting financing burdens between generations, it shifts them between payroll-taxpayers and income-taxpayers. If the problem is an intergenerational one, it can only be fixed by reallocating resources between generations—not between income classes.

3) An income tax bailout will not stabilize the worsening relationship between Social Security contributions and benefits. The “Fix-It Book” states that if general revenues are contributed to Social Security, then each generation’s payroll taxes “would closely reflect the benefits it gets.” This could well be true—but only because of the narrow specification of “payroll taxes.” Younger generations would still receive a poor deal overall from Social Security, losing on balance roughly 4 percent of their lifetime wages to the system. To propose that this income loss be manifested in higher income taxes, rather than higher payroll taxes, in no way mitigates the loss.

Over the past decade, nevertheless, a trend of opinion has developed among many on the American left that it is acceptable—even desirable—to bail out Social Security with income taxes. That gradual acclimation is real, even if the substantive case for it is flawed.

This new policy represents a monumental change in how Social Security is financed.

In the past several years, left-of-center advocates of this policy have searched for the “best” such tax subsidy. Many argued for reinstating a higher estate tax and transferring those revenues to Social Security. Former Social Security Administration Commissioner Robert Ball included such a provision in his 2005 proposal, reversing his previous position against using such revenues.

In 2008, then-Senator Obama’s presidential campaign proposed that a new Social Security tax be applied to those earning more than $250,000. In 2009, Congressman Robert Wexler proposed that a 6 percent surcharge be applied on higher earners (breaking the historical link between contributions and benefits). In 2011, Congressman Peter DeFazio proposed that incomes over $250,000 be exposed to a further 12.4 percent tax—again with no benefit credits—a proposal later introduced by Senator Bernie Sanders.

All of this represents a substantial evolution in the attitude of many on the American left toward Social Security. Though not yet a generally accepted principle, there has been widening support for the idea that Social Security’s contribution-benefit link should simply be abandoned and that beneficiaries be paid well in excess of their contributions, with the subsidy provided by higher-income taxpayers.

The recent shift to income-tax-financing embodied in President Obama’s payroll tax cut policy cannot be said to represent a bipartisan agreement with this new policy view. Instead, the payroll tax cut was first proposed on the basis that it was necessary for economic stimulus, and later extended with the argument that doing otherwise would impose a painful tax increase on working Americans. The fact that the law also contained a provision to begin significant subsidization of Social Security with income taxes only belatedly gained the notice of the press, and not yet of the general public.

A critical milestone has nevertheless been passed. Beginning in December 2010, and continuing through to the present time, the federal government has embraced the policy of committing income taxes to subsidize benefits beyond those that Social Security itself can finance. Unless this policy is rapidly reversed, readers of this article who pay income taxes should brace themselves for the substantial new taxes they will soon be paying to bail out Social Security.

Simply brilliant. The diagram of burden-benefit allocation under PAYG versus self-funding programs is, by itself, a powerful addition to the general reader's comprehension. The larger theme---that the principles underlying the old New Deal have been fatally hollowed out by the promoters of the new New Deal--- urgently needs to be communicated, and I thank the author for doing it so well.

---Owen Hughes