- History

- US

- Revitalizing History

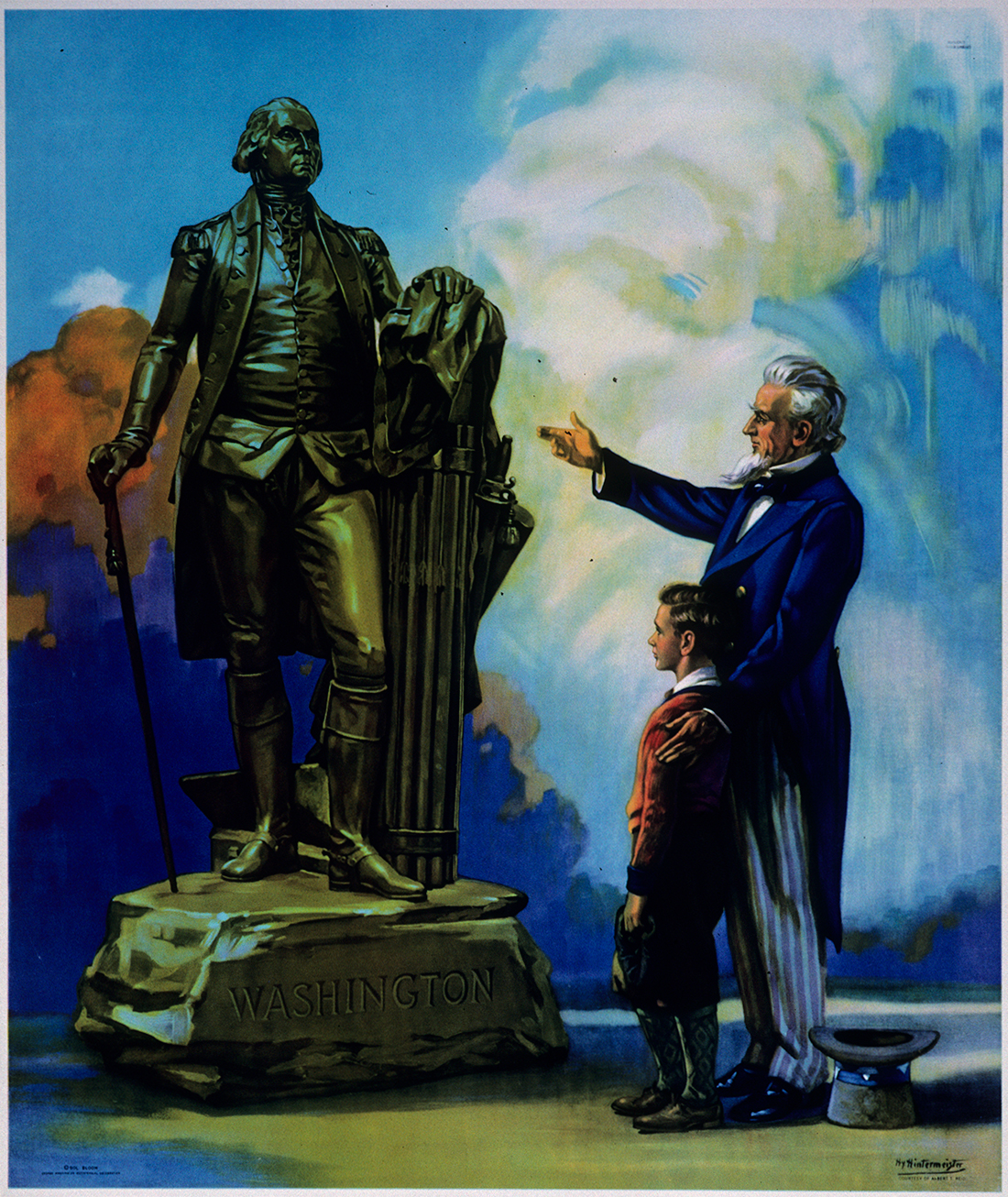

If we were assessing General George Washington strictly on battlefield wins and losses, he probably would not even make “honorable mention” among the great military leaders of all time. As historians constantly point out, he lost more than he won. Still, without Washington’s remarkable strategic brilliance (the essence of understanding what is possible at the intersection of war and politics and then knowing how best to achieve it), it’s likely we would have lost our War for Independence. Washington made an art form out of understanding the relative strengths and vulnerabilities of his and British forces in relation to the political goals pursued and learning from his mistakes, which together gave a significant advantage to the American cause. In the end, it was Washington’s appreciation and respect for the brutal realities of the conflict, combined with his courageous personal leadership on the battlefield, that allowed America to overcome and defeat the greatest military power in the world at the time.

This extraordinary capability was on display right from the start of the war when he sensed an opening after the capture of Fort Ticonderoga. Few generals at the time would have ordered an expedition to move cannons hundreds of miles over rough terrain in the middle of the winter, especially after British forces had previously displayed a versatility and aggressiveness to march on rebel guns once discovered, as they did with the Concord expedition in April 1775.

Washington knew this mission, which was hatched with Colonel Henry Knox, would take months. Had they been discovered in the process, they would have been very vulnerable to attack and defeat, which would have meant the potential loss of those key artillery pieces. Very aware of that acute operational risk, he ordered the mission anyway because he understood how strategically significant a withdrawal of British forces from Boston could be to the overall cause. If he could demonstrate that even the vaunted British Army could not hold Boston, the very center of the American Revolution at the time, then winning this war was possible. Moreover, Washington sensed that such a bold maneuver and strategic success could ultimately inspire the Continental Congress to declare independence, which then would focus and unite all of the colonies around a clear and decisive goal.

In 1776, after expelling the British from Boston in March and after the Continental Congress declared for independence in July, Washington’s sharpened sense of the overall strategic picture drove him to avoid decisive battle during operations in and around New York City throughout that summer and fall. His ability to preserve his fighting force, even after being defeated in several major engagements on Long Island and in Manhattan, prolonged the war and eventually changed the strategic calculus. Washington recognized that continued conflict would require the British to station an inordinately large field army in America, with its associated mounting financial costs, redounding to the colonists’ benefit, moving them closer to their political goal. It’s worth pointing out that a budget crisis was at the center of British efforts to extract new taxes from the colonies to pay for the debt Great Britain incurred fighting the recent French and Indian War. That acute fiscal situation was now being exacerbated by the cost of large-scale combat operations to put down the rebellion and Washington sought to exploit it.

While this may have been the optimal strategic approach for the Continental Army, Washington was also keenly aware that insurgency had its vulnerabilities and limits. Because colonial enlistments had short time commitments, it was important that his men believed their cause was righteous and winnable or they may not reenlist to stay the course of the war. This is why he ordered and personally led the bold Christmas Day 1776 crossing of the Delaware River to engage Hessian forces in Trenton during very challenging wintry conditions. Trenton was not a strategically significant city, but at the time it was vital to demonstrate to both his men, and to the British, that the soldiers of the Continental Army still had a lot of fight left in them, despite the battlefield losses suffered throughout the second half of 1776. The surprising victory at Trenton helped to achieve that.

With the taste of victory still fresh, Washington followed that up the next week with another important victory at Princeton, where he once again personally led the critical counterattack that carried the day. The combined result of these two victories helped reenlistment efforts and inspired more new recruits to join the fight. These developments ensured the continued viability of the Continental Army, prolonging the war and denying the British the quick victory they sought. As renowned historian David McCullough pointed out in his best-selling book, 1776, General Washington’s savvy strategic leadership during this period was in sharp contrast to the actions of the Continental Congress, which was paralyzed by inaction and provided very little in the way of wartime leadership that winter.

The Battle of Saratoga in October 1777 proved a turning point in the war as it led to the surrender of British General Burgoyne’s entire Northern Army, convinced the French to enter the war on America’s side, and inspired the Continental Congress to pass the Articles of Confederation, creating the appearance of a viable and functioning government of free and independent states. With these changes to the political landscape, Washington sensed that momentum was now on America’s side, a feeling that was confirmed at the Battle of Monmouth in June 1778 when Washington’s personal courage and leadership prevented the British from exploiting initial success during the battle. Afterwards, British forces withdrew back to New York City leaving the field to the Continental Army. After Monmouth, Washington doubled down on his strategic approach of exercising patience. With time now on his side, he was resolved to wait for the British to make a major mistake before committing again to decisive battle.

That is exactly what happened in 1781, when the commander of British forces in the South, General/Lord Charles Cornwallis, under pressure from his commander General Henry Clinton and from the British government in London to finish off the rebellion, began to consolidate his troops and maneuver on Continental forces in Virginia. This was the opening Washington waited for, and he designed and orchestrated a combined campaign with French forces (both Army and Naval forces) with the goal of trapping the British Army in the vicinity of Yorktown. The campaign ended up working brilliantly, buoyed by the remarkable initiative of subordinate commanders (both American and French), who seized key redoubts in the Yorktown area, completing the entrapment of Cornwallis’ army. Cornwallis surrendered on October 19th and when news of that reached London, Lord North’s government fell and the new British governing coalition that followed entered into peace negotiations to end the war.

America had won her independence. While this victory should be credited to many, including, of course, all of the brave soldiers and sailors of the Continental and French forces, and to the French government which provided considerable support, there was no denying that General Washington’s cunning and courageous leadership was decisive to achieving the ultimate political goal of independence. This was a harbinger of what was to come. Before he was done, Washington would put his imprint on the governmental structure of our new nation as well.

Chris Gibson is a decorated Army combat veteran, a former Member of Congress, and a Participant of Hoover’s Working Group on the Role of Military History in Contemporary Conflict. This essay was drawn from Gibson’s latest book, The Spirit of Philadelphia: A Call to Recover the Founding Principles, published by Routledge in 2025.