In the past five years, drones have acquired the aura of a revolutionary military technology, as a result of spectacular successes in killing Islamist militants. Drones have been the principal instrument of U.S. counterterrorism in Pakistan, the country with the largest population of dangerous international terrorists, and they have taken out targets on a smaller scale in Yemen and Somalia, the primary expansion targets for al-Qaeda. Guided remotely through satellite data links, drones employ high-resolution optical devices to see targets, and precision-guided missiles to destroy them. The absence of pilots precludes the possibility of death or capture of airmen, a consideration of much importance for nations highly averse to casualties, and makes drone strikes more palatable to foreign governments.

When the Obama administration recast its national security strategy in 2011, administration officials argued that drones could take the place of conventional land forces. Drones, it was said, could eliminate terrorists without the large military footprints that had been planted in Iraq and Afghanistan. This argument was ultimately invoked to justify slashing the Army and Marine Corps by over 100,000 troops.

Drones do not, in actuality, meet the threshold of a revolutionary development in warfare. The technology itself is not revolutionary, but is instead an evolutionary combination of several existing technologies—propeller aircraft, video cameras, precision munitions, and satellite data transmission. While some of those technologies experienced rapid advances in the years preceding the development of the combat drone, all had existed for decades.

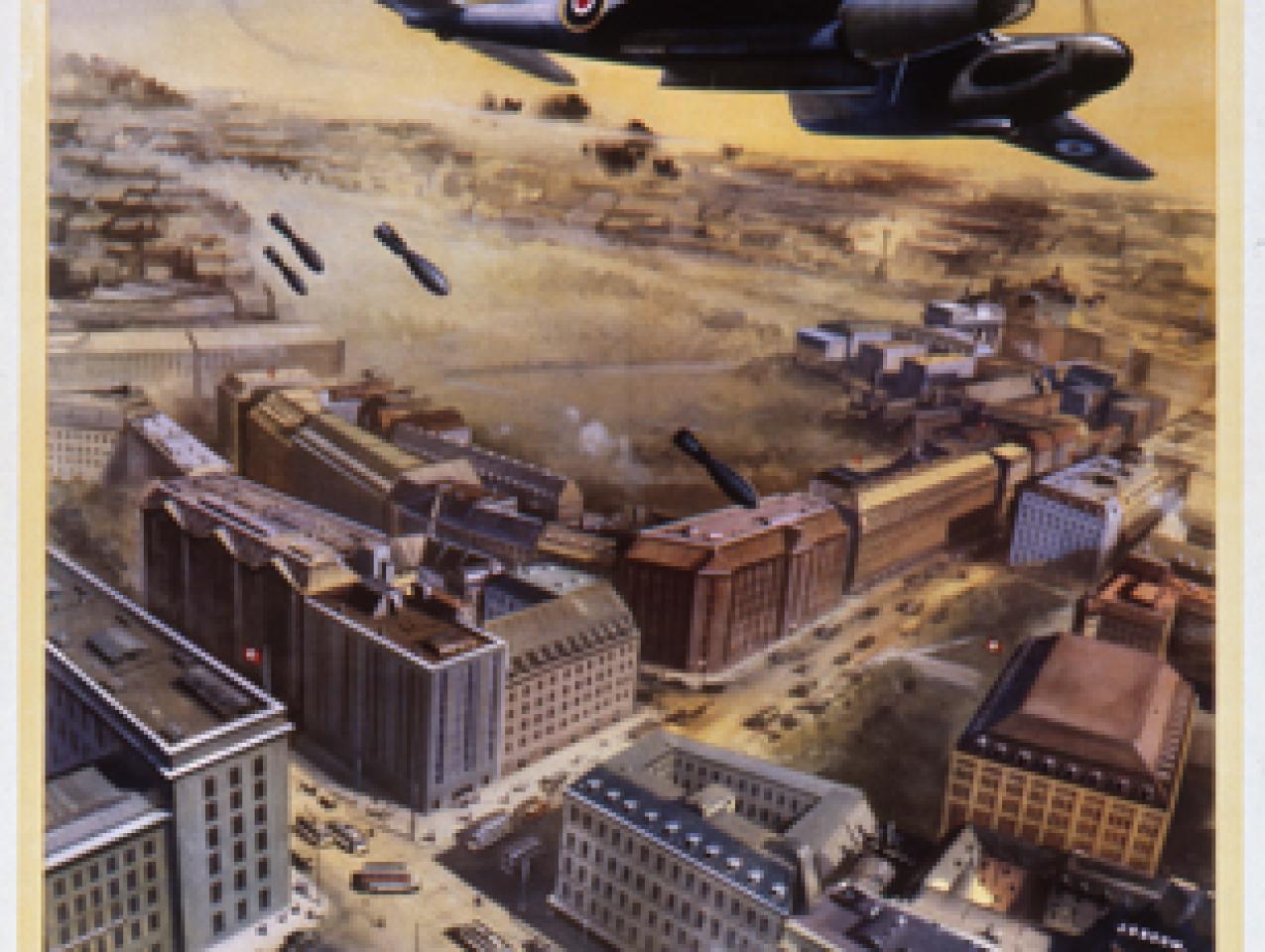

The amalgamation of existing technologies can effect a military revolution, but only if the character of war undergoes fundamental change. The aircraft carrier, for instance, fused the armored warship with manned aircraft in creating a revolutionary weapons platform. Bearing aircraft that could scan huge areas and annihilate the hitherto mighty battleship, they revolutionized naval warfare.

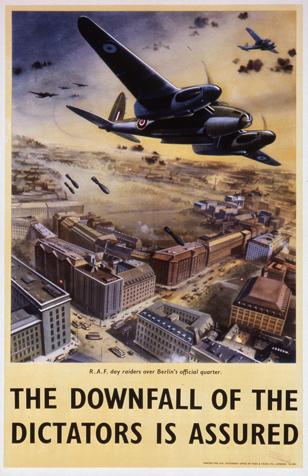

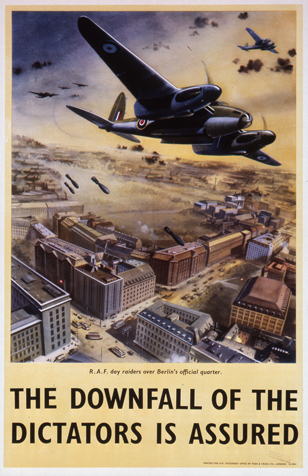

Drones have not had a comparable impact on war’s character. In contrast to weapon systems that revolutionized warfare through their offensive power, like the aircraft carrier and the machine gun, drones have not yielded a dramatic increase in the user’s mobility, firepower, or accuracy. Propeller aircraft have been attacking targets from the air since World War I, and they have been employing precision munitions since the Vietnam War.

Nor do drones have exceptional defensive capabilities, of the sort that allowed innovations like the ironclad ship and the tank to initiate revolutionary change. Because of their heat and noise signatures and their slow flying speeds, drones are easy to destroy with air-to-air or surface-to-air missiles. This vulnerability, indeed, helps account for the inability of the drone to revolutionize warfare. Had the machine gun or the helicopter been so vulnerable, they would not have been able to alter the character of warfare on a global scale.

The machine gun made its way into conflicts of the late nineteenth century across the planet, transforming the conduct of land warfare from the War of the Pacific to the Boer Wars to the Russo-Turkish War. In the late twentieth century, the helicopter carried infantrymen into the rice paddies of Vietnam, the jungles of Colombia, and the mountains of Afghanistan. The dramatic successes of drones, by contrast, have been confined to a few countries, where one finds an unusual confluence of favorable circumstances.

First, drones can function effectively only where hostile forces have no presence in the air and possess no surface-to-air missiles. Second, drone operations require bases and overflight permissions from one or more governments in the vicinity of the targets. Third, the success of drone strikes depends on targeting information collected on the ground, which can be obtained only if the local government provides it or allows a foreign intelligence service to collect it. These conditions prevail simultaneously in only a handful of countries.

The use of drones has, in and of itself, increased the difficulty of finding countries that meet the three conditions. U.S. drone strikes have generated fierce opposition among the publics of Pakistan and Yemen, causing the Pakistani and Yemeni governments to impose greater restrictions on American drone programs. At some point, those governments could stop the strikes altogether.

While drones retain value as an offensive weapon, they cannot defeat extremists in a country by themselves. Al-Qaeda and other non-state organizations have been able to survive extensive damage from drone strikes wherever they have been employed. Vanquishing extremist organizations requires ground forces that can secure the population and dismantle remote bases. The United States, having slashed its land power based on excessive confidence in drones, must now rely on the ground forces of other nations. As recent events in Libya, Pakistan, Yemen, and elsewhere have made regrettably clear, the intentions and capabilities of those nations leave much to be desired.