- China

- History

- Revitalizing History

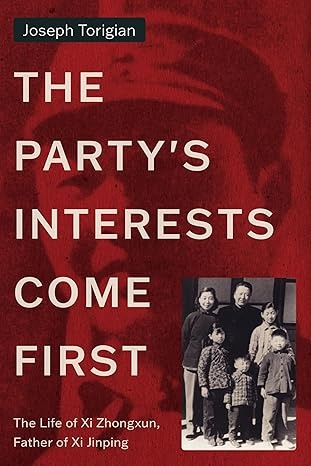

One way to examine the thinking and ruling style of Chinese President Xi Jinping: his father’s role in the rise and evolution of Chinese-brand communism. Hoover research fellow Joseph Torigian, author of the recently released The Party’s Interests Come First: The Life of Xi Zhongxun, Father of Xi Jinping, discusses how the elder Xi’s involvement in the Red Army, economic political reform, working alongside Zhou Enlai and dealing with ethnic minorities and organized religion – plus years of political exile after running afoul of Maoist sensibilities – all play into how his son runs the modern-day Chinese Communist Party.

WATCH THE EPISODE

>> Bill Whalen: It's Friday, July 25, 2025. And welcome back to Matters of Policy and Politics, a Hoover Institution podcast devoted to governance and balance of power here in America and around the world. I'm Bill Whelan. I'm the Virginia Hobbs Carpenter Distinguished Policy Fellow in Journalism here at the Hoover Institution.

I'm not the only Hoover fellow who's podcasting these days. And if you don't trust me, go to our website, which is hoover.org/podcast, and you'll see the whole lineup of podcasts there. That includes, by the way, the audio version of the Goodfellows show that we do for YouTube with Neil Ferguson, John Cochrane, and H.R. McMaster.

So definitely check that out. Today we turn our attention to the other side of the Pacific Rim, and that would be China, specifically Chinese leadership and the man behind the man, if you will, the father of the current president of China. And joining me today for this conversation is Joseph Turigian.

Joseph Turigian is a Hoover Institution research fellow as well as an associate professor at American University School of International Service. He is the author of the recent release book titled the Party's Interest Comes First. It's a biography of a gentleman named Xi Jeongjun, the father of China's President Xi Jinping.

Joseph, thanks for coming on the podcast.

>> Joseph Torigian: Thanks so much for having me.

>> Bill Whalen: And I'll apologize for butchering the father's name, you correct me on that. The correct pronunciation is?

>> Joseph Torigian: Xi Zhongshun.

>> Bill Whalen: Thank you. Very, very well done.

>> Joseph Torigian: You were close.

>> Bill Whalen: Thank you. Well-

>> Joseph Torigian: Very close.

>> Bill Whalen: I tried. One thing I did mention in the intro is that one of the things you do at Hoover is you are involved in Hoover's history lab. Can you tell us a bit about the history lab?

>> Joseph Torigian: Yeah. So Stephen Kotkin created the Hoover History Lab because he thought, like the people that he has been bringing to the lab, that you can learn a lot from history to understand what's going on.

Today, I've taught as part of this lab at Stanford, a class on Chinese and Russian politics and foreign policy that combines history with theory and method and tries to give people a sense of what happened in the past so they have the analytical lens to get a sense of what's going on in those countries today.

>> Bill Whalen: And I should point out that this book is actually part of a Stanford Hoover series on authoritarianism, correct?

>> Joseph Torigian: That's correct. And there's another synergy here, which is that I used many, many materials from the Hoover archives, including the spectacular diaries of a man named Li Ray who worked directly for Mao Zedong and knew the Xi family.

>> Bill Whalen: Okay, so let me ask you a question. At summertime, people are taking books with them when they travel. If I ask you to give me three books on authoritarianism in addition to yours, three more book books, Suggest three books for me. Would you give me, say, Steve Calkins books on Stalin?

>> Joseph Torigian: You took one away from me. I certainly would have suggested his books. I also love David Holloway's books and he is emeritus at Stanford, especially his Stalin and the Bomb. I think that is a wonderful book. I also am a big fan of Fred Tevis and Warren Sun.

Their last book is about China in the last years of the Cultural Revolution. I think that's a terrific book. And for the third book, there are so many different possibilities. I'd have to think about that for a second. I'm curious while I think, do you have one that you would recommend?

>> Bill Whalen: No, I was gonna. I think I shot my wad with Kotkin and Stalin, if you will, your knowledge on more than me. But let's take this a different way. If you were to do a Mount Rushmore of authoritarian figures, let's say for the 20th century, who would you put up there?

You have four choices, let's assume maybe Mao and Stalin or two of them.

>> Joseph Torigian: That's also a really terrific question. I probably would put one member of the Kim family up there in North Korea. I have done some work on North Korea. There's another talk that I gave at aparc, which is also at Stanford, where I reflected on where Russia and China and North Korea find themselves this year for the anniversary and the parade that Vladimir Putin had in Moscow in May for the fourth one.

That's a terrific question. Actually, it's not a book, it's a movie. But in terms of a cultural product that I would suggest for people who want to get a sense of authoritarianism, there was an Iranian movie. Your listeners will be able to find it if I give them enough information.

But it's something that the Fig Tree that came out, I think, this year or the year before about authoritarianism in Iran. And I think that is really a spectacular movie to watch because it deals with a lot of the themes that come out in my book on Xi Zhongfin, generational politics, how you keep the revolution alive, the relationship between the state and society, how you use carrots and sticks at the same time, but most importantly, what it does to figures who are members of these regimes when they do have their own views, but ultimately put the interests of the regime first.

And what it means morally and what it means practically for them and their families,

>> Bill Whalen: right? So, Joseph, Fathers and sons is a favorite trope of American political journalist. If you were to run for the presidency and getting traction and getting somewhere, invariably somebody would run a piece and they'd want to talk about how Joseph Trigian is or is not a product of his father, how his old man rubbed off on him, and et cetera.

I would contend this is a very hit or miss proposition when it comes to American politics. If you want to try to psychoanalyze Donald Trump. I'm not sure if Fred Trump is where I would go for Trump being his father, but if I were psychoanalyzing John F. Kennedy, and I've been reading Kennedy books lately, yeah, I would make a beeline to Joseph Patrick Kennedy.

But in this case, it's very easy to do, in part because there is a treasure trove of information Jon Joe Kennedy, JFK, the Kennedys in general. You could go to the Kennedy library, you could go to the FDR library, as the elder Kennedy was his ambassador to Britain.

You could go to newspaper archives. You could find just a ton of books to write on. Pretty easy stuff. But I'm assuming when you're writing about Xi Jinping's father, it's not like there's a lot of information there in front of you. So tell us where you went digging.

You mentioned, for example, the Hoover archives.

>> Joseph Torigian: Well, you're right. When you write a book about a political family, the psychological element has to be there. You have to at least broach it, because otherwise the people who read your book are going to be very disappointed. And so many people who've reviewed the book, they focused on this, Right.

Like what it meant for Xi Jinping as a young person to grow up in this family. But, you know, what I tried to do with the book as well was to depict what it was like to be a member of the Chinese Communist party during the 20th century and to use the story of Xi Jinping's father to get a sense of what its membership went through and what.

And what the country went through. And the other reason, I think, you know, we need to be careful with the psychological aspect, especially for the book that I just wrote, which is that the details are scarce. Right. And so when you talk to professionals who work in mental health, they refuse to diagnose people from afar.

Right. It's part of their guild. And I'm not even trained in mental health. Right. So I included the material that I did know about, but I didn't want to essentialize the whole story of Xi Jinping down to what he experienced when he was, was a young person. And so, what do you do when the evidence is so scattered?

Well, it's not just scattered for Xi Jinping for reasons that emerge from my book. He thinks about history all the time because he has this view that one of the reasons the Soviet Union collapsed is they lost control of their history and nobody believed in it anymore. And so for Xi Jinping, a member of a Leninist party, he has this idea, this fixation that if you don't see the past as one victory to another, people won't sacrifice for that kind of an organization.

And for him the party is all about putting the interests of the organization ahead of your own right. And so you can't just go to one archive and collect the evidence and then write it up. You need to have a sensitivity to possibilities and not limitations, and so bring a sort of detective.

Detective mindset, or maybe a journalist mindset, and just keep collecting materials that are of a variety of different backgrounds and spend a lot of time on it, contextualize everything that you have and then create a mosaic where you have some things colored in better, but other elements remain a little bit less understood or even a bit of a mystery.

So one thing that I did is I made a list of every time Xi Jinping's father met with a foreigner and I interviewed that foreigner or I went to their archives. There was a lot of material published outside of mainland censorship in Hong Kong and Taiwan. There was an ability to go to China to collect materials and speak to people.

Even their official sources can be quite significant, right? So in terms of just mining biographical details, or you take that kind of thing and put it in the context of something you got from somewhere else and suddenly it's very meaningful. And then finally you have material that's kind of gotten out of the party in one way or another that's intended for internal circulation.

I mentioned the Lee Ray diaries earlier, but there's actually also a lot of documents that are available at places like Stanford and Princeton that because they lost control over their archives during the Cultural Revolution, are actually now more available in the United States than they are in China.

>> Bill Whalen: You know, American politics changed vastly in 1992, Joseph, when Bill Clinton and Al Gore ran on the Democratic ticket, both gentlemen were more than happy to stretch themselves on the couch and talk about their fathers. In Clinton's case, it was the biological father. He never knew. Remember, his father died in a car crash.

Al Gore's case, his father was a senator and was apparently very hard to please. So the younger Gore talked about inadequacies and trying to live up to the old man's expectations. But I, I assume that there is no such equivalent of People magazine in China. And I don't think you're going to find Xi Jinping on record talking much about his father.

>> Joseph Torigian: So he does talk about his father,

>> Bill Whalen: does he?

>> Joseph Torigian: And so, but we have to understand that when you have figures like Xi Jinping or other high ranking members of the elite, they have their own views, and then they have the views that they think that they express publicly.

And we can't immediately assume that everything is a lie. And it's also meaningful to think about why they portray the past in a particular way. And so when I look at what Xi Jinping said about his father, even when he is mischaracterizing things to a more or less extent, that itself also is very revealing.

>> Bill Whalen: Let's talk about the father. So the father is born in October of 1913. He dies in May of 2002. So he lives about 90 years. Good run. He joins the Communist youth league in 1926. So he is 12 going on 13 at the time. Why would he join the Communist Youth League at that time?

Was it the cool thing to do? Was he running away from something? Was he running towards something?

>> Joseph Torigian: Yeah. So let's talk about what kind of milieu he was growing up in. He was born two years after the collapse of the Qing Dynasty. He was born Shanxi, near the city of Xi'.

An. Xi' an had been the capital from which Chinese emperors had ruled for millennia. Many of your listeners probably have heard of the terracotta soldiers. That's why they are in Xi', an, is because the first unified Chinese state was created there. But by the time xijungfinha was born, this was an area that had suffered years of banditry and famine and civil war.

And the whole country, of course, was facing encroachments from the west and Japan. And so there was a sense that something needed to change. There was a sense that the country needed to be saved. And interestingly enough, in his early years, the Communists were in an alliance with the Nationalists, right?

So they were working together through much of the 1920s against the warlords. And so there was an opening for Xi Zhongshun to read Communist literature. Now, use the word cool. That's actually quite a good term to use, because at this age, he didn't really understand Marx. He didn't really understand Das Kapital.

He wasn't really ruminating on the finer points of this ideology, but there was a sense that radicalism and being more radical was better than being less radical. And so when you're a student and your country is facing those kinds of extraordinary challenges, it's conducive to you to think in this kind of way, I think.

And that's what happened to Xi Zhongxun

>> Bill Whalen: in the 1930s. He joins the Red Army.

>> Joseph Torigian: So he joins the Chinese Communist Party in prison. And then the Nationalists, of course, did betray the Communists butchered and massacred many of them, including within Shaanxi. And then Xi Zhongshun, even though he's a wanted man, is sent to join the local Nationalist force undercover in hopes of convincing them to do an insurrection.

The insurrection is another failure. And then he goes to the base areas because the Party realized that you're not going to win in the cities. The cities are just not the right place for you to eke victories. And so they start to gradually move in this direction of first building up their forces in areas that are much harder for the Nationalists to control.

>> Bill Whalen: And how does he fit into the greater scheme of the army? What is his specialty? What is his forte?

>> Joseph Torigian: You know, it's interesting, right? So he wasn't a military figure and he wasn't really the one who was devising campaigns. And that doesn't mean that he was an insignificant person.

It does mean that he wasn't. You know, he didn't. You got a lot of prestigious status by being a good war fighter, right? I mean, that's how Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping became so respected. But he was good at logistics, he was good at governance, but he was especially good on at the so called united front.

So what's the United Front? Well, it's what the party calls its efforts to empower and work with allies that are not members of the party and then co opt and win over people who are sort of in the middle. And so during the revolution, Xi Jin was really good at, or at least he became better and better.

It was not exactly easy at finding Nationalists who he could convince to either work for the communists or at least not actively work against them. And so what he took the greatest pride in during the war against the Nationalists was his ability essentially to use political operations, of course, in conjunction with military force to affect those kinds of outcomes.

>> Bill Whalen: Okay, he has a connection to Zhou Enlai.

>> Joseph Torigian: Yeah, so Zhou Enlai, of course, maybe along with Mao and Dong, one of the most famous members of the Chinese Communist party during the 20th century. And you know, there's this idea I think, among a lot of people who watch China from the outside, that it's a story of good guys and bad guys.

And as more evidence is coming out, Zhou is coming out as a more complicated figure. And that is part of what we see in my book as well. So Xi Zhongshun was sort of Zhou Enlai's right hand man for much of the 1950s, early 1960s. And Xi Zhongshun would have seen certain things.

He would have seen how Mao ritually and regularly humiliated Zhou Enlai. He would have seen how when the Great Leap Forward started, Zhou Enlai was forced to give a very long self criticism. He would have seen how Zhou Enlai would have facilitated the Great Leap even as it was becoming increasingly clear that it was the disaster.

And we see in the 1980s there was this moment where the party leadership was debating whether to destroy the documents that were the most incriminating about Zhou Enlai and Xi Chung as part of those conversations, those documents were destroyed. And it was around that time, as we know from Li Ray's diaries, that Xi Zhengxun expressed a somewhat negative opinion of Zhou.

And we don't know. Exactly what that was, but he knew Joe well and he saw those documents.

>> Bill Whalen: And he also works for someone who's less of a Chinese household name, and that is Hu Yao Bang, but he is involved in economic political reform.

>> Joseph Torigian: So, yeah, it's very interesting.

Right. So Joan Lai was the chief implementer for mao in the 1950s, and Huyaobang was sort of the chief implementer for Deng xiaoping in the 1980s. And Xi Jinping was the right-hand man for both of those periods, so it was really a front row seat to seeing how the elite works.

And history kind of repeats itself both in the 50s and 80s, where you have these deputies, Zhou Enlai and then Hu Yaobang, who are both totally loyal to Mao, totally dedicated to Mao, and then. And then to Deng again in the 1980s. And there are different figures, Zhou Enlai and Hu Yaobang.

Zhou Enlai was very careful. Hu Yaobang was a little bit less careful. But they both really, really struggled to manage their relationship with the top leader. Part of that was related to succession politics. Part of that was related to the fact that Mao and Dong weren't always exactly sure what they wanted to do and that they changed their mind and that there were other competitors within the elite that didn't like them.

And Xi Zhongsheng would have seen all of it. And I write about it in my book.

>> Bill Whalen: Okay. Two other aspects of his career that caught my eye. He's involved in the party's efforts with ethnic minorities, Uyghurs, for example.

>> Joseph Torigian: Yeah, in a way. The book is also a book about how China at different times, has thought about different models for its relationship with ethnic minorities.

And so in the last years of the 1940s and early years of the 1950s, Xi Zhongshun was the leader of the so called Northwest Bureau, which included a huge part of what is now the People's Republic of China, including Uyghurs in Xinjiang, as well as Tibetans who lived in Gansu and Shanghai.

And Xi Jinping was sort of figuring things out. He was trying to figure out when you use repression, but also when you try to win people over by empowering them and co opting them and bringing them into the regime as supporters. And the story of the 1950s is a story of gradually moving away from that.

And by 1958, it's literally a war by the party against its own people. And precisely these areas that Xi Zhongxun had helped incorporate into the PRC. And then in the 1980s, Xi Zhongshun when he's working for Hu Yaobang, one of his primary tasks is managing relations with ethnic minorities.

And so we see him negotiating with the Dalai Lama's emissaries in Beijing. We see him purging the leaders of the Tibet Autonomous Region because he thinks they're too conservative. And we also see by the end of the 1980s, the party deciding that this model that they had experimented with after the Cultural Revolution of economic growth and bringing religion into the open to better control it and co opting grievances, that in their mind it just empowered people to hurt the party as opposed to, as opposed to win them over.

And that's a problematic conclusion to draw. But Xi Junction was at the very center of those debates.

>> Bill Whalen: And at one point, Joseph, he is the party's point person on Catholicism in China. Can you explain how organized religion gets along with a state like China, which does not believe in religion, just does not want to encourage religion?

How do the two coincide?

>> Joseph Torigian: Yeah. You know, it's funny, when I give talks about Xi Zhongsheng, one of the themes that I discuss is how this is a person who saw a lot of meaning in forging and suffering, right? And that he would take pride in the fact that he suffered more than others.

He saw it as a kind of way of credentialing his status within the party. And sometimes people who went to Catholic school for high school will come up to me after my talk is over and say there's certain things that are a little bit familiar to me. And so when Xijong hin was dealing with Catholics, even in these party texts, you get a sense that they see something a little familiar there, which is, you know, a group of people for whom religion, by which I mean, you know, the Catholics, that that is the defining feature of their lives.

It's very hierarchical, right? You have the Pope and everyone is supposed to listen to the Pope. You have these set of texts, but then you also need to discern what the texts mean. And so she and the other people around him are like, wow, these are not easy people to deal with.

And they talk about how they're very well organized, how they're the ones infiltrating the party. And so they, they struggle with what the right approach is, right? Because on the one hand, what you can do is think about how you recognize what the Catholic's own challenges are, and then you work with them to better co opt them.

And you need to figure out who's on your side and empower them and who's not and weaken them, and you also need to figure out what to do about the Vatican, right? Like, this is really the sticking point for them because they see the Catholic Church essentially as a tool of the imperialists, especially American imperialists.

And so you have these wild speeches by people like Xi Zhongshun, where you have a very sort of thoughtful set of remarks about that sort of show that he intuits what kind of situation the Catholics find themselves in. And then you see this really radical, leftist, communist, you know, aggressive sort of sometimes in the same speech, right?

And what's interesting is he also at one point said about some priests that they needed to be more devout so that they could act as better representatives of the party within their own communities, right? And so then when you look at the Catholics and they're in a moral quandary, right, because they want to be loyal to the Vatican, they want to be loyal to their beliefs, but at the same time, they want to protect their flock, and they want to make sure that there's space for what they're doing.

And so they're put in this very, very difficult position both in the 1950s and then, and then again in the 1980s when, which are the two periods in which Xi Zhongsheng is most prominently involved in Catholic affairs.

>> Bill Whalen: What would happen today if you were Chinese and you walked around Shanghai or Beijing with a cross around your neck?

>> Joseph Torigian: I think you would. You would be okay. There is now actually an agreement between the Vatican and Beijing. And so the details are scarce. We don't know a lot about them, but it seems that there is some kind of an understanding about the, I mean the crux is who selects bishops and cardinals and how they're consecrated, that is the central issue here, right?

And so it seems like there some bumps in the road. Right. But technically, as opposed to a few years ago, if you go to an open church, as opposed to an underground church and take communion, that that's considered approved by the Catholic Church. Right. And so people have been skeptical or critical of certain elements of the agreement.

I've heard stories that that might even have affected a little bit of the deliberations about the new pope, although I'm not an expert on that, but on the. And so it's interesting, too, right, because it speaks to this theme that keeps coming out in our conversation, Bill, which is the party has always had the soft side, but also a hard side.

Right. Because we've also seen churches in Zhejiang province have the, the crosses ripped down. Right. So and we also know that Xi Jinping has brought a very much more conservative approach to religion more generally. Nevertheless, it's under his leadership that an agreement with the Vatican was struck. Right.

So you have this sort of like, if you're good to me, I'll be. I'll be good to you, and if you're bad to me, I'll be, I'll be bad to you. And. And you can see how that works in theory. But sometimes it's hard to get right, right?

Because if you're too tough, then the friendly things don't work, and if you're too friendly, then people, you're afraid that people might take you for a ride. And so this is just kind of a central. Dilemma that has been in the party from the very beginning. And one that's particularly hard, I think, between the party and Catholics for all of these reasons that I just discussed with you.

>> Bill Whalen: And I want to build on more of that in a minute, but let's close out with more on the father here. So throughout his long and we'd agree, storied career with China, the Chinese Party, this phrase is applied to him. It's the phrase is, quote, top deputy to the top deputy.

Why was he never the top deputy?

>> Joseph Torigian: Yeah, that's a good question. So Xi Junction's age is also worth talking about, right? Because he kept, for much of his life, up until his 40s, was the youngest person at the highest levels that he reached, right?

>> Bill Whalen: Yeah, he's between.

He's between generations. He is because.

>> Joseph Torigian: Exactly.

>> Bill Whalen: Man was born about what, 20 years before him, right?

>> Joseph Torigian: So he was the youngest candidate member to the central committee in 1945 at the seventh party congress. He was the youngest of the so called five horses that entered the capital.

For your listeners, this is a very important and famous moment in Chinese history when these major regional figures went to Beijing. Deng Xiaoping was another one of them. He was another one of the big horses. And then in 1959, Xi Zhongsheng became by far the youngest vice premier.

And that meant he was really at the center of power. And then in the 80s, he starts working for Hu Yaobang. But his seniority and status and experience vastly outweighs Hu Yaobang, Right? And then the question becomes, why wasn't Xi Zhongshun the General secretary? And I think that we can only guess, but it probably had something to do with the fact that Deng Xiaoping likely did not completely trust him because they had had these differences over a variety of issues over the 1950s and early 1960s, possibly because Xi Junction was not a long marcher, right?

As I said before, he was from the northwest. He was there when the Long March arrived. And so he didn't have this kind of cachet that other people did. He also was a little excitable sometimes. So that also might have hurt his chances. But there were all of these rumors throughout the 1980s that he would maybe not be like the top leader, like a dong, but at least maybe, maybe like a leader of the Chinese legislature or the General secretary, if not the top leader, but maybe the chief implementer or one of the chief implementers.

But that never happened. And in fact, that rankled him because this is a system in which your position is supposed to reflect your status that is rooted in when you joined the party, what you did for the party, and how you were at these various congresses and what you were selected to.

>> Bill Whalen: Now, at one point, he falls into a very bad pothole. He falls out of favor with the Party. He is confined in near isolation in Beijing. I believe you're right. It's a room of 7-8 square meters at the most. What did he do to earn this punishment?

>> Joseph Torigian: Well, the quick answer,

>> Bill Whalen: more to the. Point, why did they decide to punish him like this?

>> Joseph Torigian: Yeah. So the answer is that he facilitated the writing of a novel. And of course, to explain why facilitating the writing of a novel would lead to 16 years of political persecution that included exile, struggle, sessions, incarceration, you need to look at several different things.

One is, you know what this novel was about? Well, as I said earlier, Xi Zhongshun was from the Northwest, right? And one of his great mentors there was a man named Liu Zhudan, and Leo Zhedong was killed in the 1930s. It was probably killed because the party didn't completely trust him, and he wanted to prove how dedicated he was.

This is a theme that emerges in the book over and over, that when the Party is bad to you, you're even better to the Party so that you can turn things around. It's actually a source of motivation and not alienation. But not everyone from the Northwest liked Liuchidan.

There were all. There was all this infighting. Right. And so when this novel appeared, some people thought that it was not reflective of what the history was all about. And so they complained to the top leadership, and then Mao reacts very strongly. So why would Mao react so strongly to this?

Well, Mao had this idea that in the aftermath of the Great Leap Forward, people weren't intuiting what he wanted. Well, and he didn't see this as just a natural divergence of objective people. He saw it as a manifestation of what. Of what he called class struggle. And so there were all of these figures who were clamoring for rehabilitation.

One of them was quite close to Xijongshin, a man named Peng Dehuai, who was the defense Minister purged in 1959 because of expressing in cautious terms concerns about the trajectory of the leap. But there was also other people who didn't like Xi or wanted to go after Xi in a way that would impress Mao.

One of those people's people was Deng Xiaoping, actually. And so Mao Zedong made this really curious and interesting remark, which is that, isn't it interesting now that people have invented the use of novels to engage in party struggle. And people are using things like novels to create the conditions for a coup.

And I don't know if Mao actually believed that or he decided that talking about it in a particular way was useful for a political purpose, but it signified Xi Zhongshun's purge from the leadership.

>> Bill Whalen: The younger Xi Joseph would have been about, what, nine, ten years old when this happened.

>> Joseph Torigian: So he was born xi Jinping in 1953, in June. And these terrible things began happening to xijongshin over the summer and fall of 1962. So Xi Jinping would have been very young.

>> Bill Whalen: Very young. The family is leaves Beijing. They end up living in a. In a cave, the house carved into a cave.

My question is this. You see this happen to your father. Your father is a political prisoner for the better part. Mention of a decade and a half. Why do you want to join a party that does that to your father?

>> Joseph Torigian: Well, you know, what meaning you find in suffering is both a personal thing and a sociological thing, right?

So we can think about this in generational terms, but also how people react to something like that is very revealing about them as an individual at the same time. And so many people went through suffering. Many people saw what happened to their family. Now, Xi Jinping said he suffered more than most, right, because his father was purged in 1962, which was several years before the Cultural revolution, when most of the other people were from the top elite were persecuted.

You know, some of the children who were growing up during the Cultural revolution, they came out of this and said, I don't believe in anything anymore. I want to make money. I want to have fun. I want to study overseas. Others said we need to figure out a way of making sure this never happens again.

And the answer is preventing another strongman leader from appearing and using the rule of law to protect individual rights. And Xi Jinping, he has admitted that after he went through all of these terrible hardships in the Cultural Revolution, that he had a moment of doubt, but that because he went through that doubt and returned to it, that his faith in the cause is even stronger than anyone else's, and that it's only the party that can hold China together to stop another Cultural Revolution from happening, and that you need a strong leader to hold things together, and that's more necessary than constraining a strong leader who has the power to start a Cultural Revolution.

Which is an interesting reaction, right? But it's also the same reaction that Deng Xiaoping had. But remember, this is a Leninist. Systems are organizational weapons. Right. And so they're designed so that you have a leader that's firewalled from political considerations, so that he can rally people up and force them to do things that may not be popular.

That's what the organization is all about. And we can see how powerful. That kind of an organization is. But we can also see why it can also lead to tragedies like the. Cultural Revolution,

>> Bill Whalen: to the adage of like father, like son. How does that apply here with Xi Jinping?

>> Joseph Torigian: So there was this understanding of Xi Zhongshen among many in the elite and intellectuals and even some regular Chinese, that he was the most humane, reformist kind of figure that the party could produce. And there were even some suggestions that one of the reasons Xi Jinping was Was elected to be the successor had something to do with his father's reputation.

And we see after 2012, when Xi Jinping is the leader, that a lot of individuals who watched what he was doing still thought that sooner or later he would become a reformer partly because of who his father was. And when that didn't happen, they then used their memory of his father as a weapon against Xi Jinping, saying that, for example, one quote from one Chinese dissident intellectual who lives in the states, that it turns out that Xi Jinping is not the son of Xi Zhongshun, but the grandson of Mao Zedong, right?

So in that sense, people are saying that he's very different from the father, and they use it in a way that they hope hurt him politically. But, you know, the question then becomes, is that true? And is that how Xi Jinping thinks about himself? Does Xi Jinping think that his father was a failure and therefore he's doing a different direction?

I don't think so. In fact, I probably think Xi Jinping hates it when people use certain things that his father said as a way of criticizing him. I think that Xi Jinping probably thinks that his father was totally dedicated to the revolution and that the question is, how could I betray the revolution for which my father suffered so much?

And so he wants to figure out a way of getting the regime back into a better position. And he may be doing things that are different from what was going on when his father was in power. And you can maybe guess that in some ways he thinks, yeah, my father didn't quite get this right.

But he also, Xi Jinping openly reflects on the relationship between legacy and innovation. And he says that the true way of respecting legacy is by innovating, because if all you do is what your forebears did, you're not adapting, you're not meeting the new situation. And the situation does change.

And of course, he needs to tell a message about what he's doing differently and better than his predecessors as a part of legitimation narrative. So my own guess is that Xi Jinping doesn't believe that he is rejecting his father's cause, but thinks that the big picture is still the same, even as he is doing certain things differently because the situation demands it or because the party is learning new things.

>> Bill Whalen: Speaking of like father, like son, Joseph, does Xi Jinping have sons of his own? And if so, did any of them show signs of political aspirations?

>> Joseph Torigian: He has a daughter who went to Harvard, actually, and I learned many years later that she and I were in the same room at one point.

So I was doing my dissertation at mit, but I was a huge fan of a Harvard professor named Roderick McFarquar, and he was on a panel to discuss the fall of Bo Xilai. You might have heard that name before. He was this brawler who was the leader of Chongqing, a megacity in China's southwest, whose father knew Xi Zhongshun, by the way.

But this panel was about the fall of bo Xilai, and McFarlane and others were talking about Chinese politics as this sort of dog eat dog world of, you know, and I would have loved to know, you know, what she was thinking when she was hearing these people talk about her father and the nature of the party.

She appeared indirectly in a newspaper article around 2008, when there were. I think that's the right date, when there were these earthquakes in Sichuan province. And Xi Jinping's wife was talking about how their child went to engage in forging and to be one with the people by going to help these Sichuanese who had suffered because of the earthquake.

And she's mysterious, but she did. Her name did reappear again recently in a. In a curious way, which was that the Belarusian news media reported that she was present when Lukashenka met with Xi Jinping just a few weeks ago. And people have been wondering what that means. Who knows?

I don't.

>> Bill Whalen: Does gender rule her out for holding power?

>> Joseph Torigian: We're really getting into conjecture here, right? I think probably the more interesting person to watch right now is Peng Liyuan, who is the wife of Xi Jinping. She seems to have a meaningful political role that people are curious about.

It would be quite something if Xi Jinping is moving in the direction of installing his daughter. You know, she's married, at least that's my understanding. And there's other male heirs. But my own sense is that he likely would have the power to do what he wants, but that it would be.

It would. And you could see why he would want to trust his own family members. But at the same time, the reputational costs within the party that even if he could, you know, engineer that kind of outcome, it may not be useful to him given all of the other disadvantages that would come from turning China into another North Korea.

Coincidentally,

>> Bill Whalen: speaking of North Korea, there's speculation. That, you know, Kim's sister could somehow take over. Take over.

>> Joseph Torigian: Or his daughter. Or his daughter.

>> Bill Whalen: But it would not be, would not be a clean process, would it?

>> Joseph Torigian: Well, you know what's interesting too, right, Is if you read my book in the 1980s, I talk about how when Kim Il Sung went to Beijing and said I want to have a handoff to my son, the Chinese were initially skeptical.

And when the Chinese decided to support it, who did they send to Pyongyang to signal it was Xi Junction? And when Kim Jong Il visited China for the first time, who hosted him for certain events? Xi Zhongshun. There's a really interesting video you can find of Xi Zhongshen sitting next to Kim Jong Il watching Pang Liyuen sing Arirang.

And this was several years before Peng Liyuan and Xi Jinping even met. And Xi Jinping showed that video to Kim Jong Un when he visited Beijing a few years ago. It's a family business in some ways.

>> Bill Whalen: Let's close out Joseph with a few thoughts on generational leadership in China.

Here in America, we have been governed by baby boomer presidents. My gosh, going back to Bill Clinton. The entire post Cold War era in America has had Presidents born between 1946 and 19. Let's see, Obama's born in 61, I believe so Cold War presidents. China, though in theory, like America, will at one point turn to younger leadership.

And here's my question for you. Going back to Joseph Kennedy. Joe Kennedy groomed his son for political office. He going back to running for the House, the Senate, the presidency. The father was always there providing money, pulling strings, making things happen. Is political grooming possible in China? Is political grooming done in China?

Let's say that you were wealthy, you had political aspirations. Could you send your son to an American college and put that son on a political path or is it done in a different way?

>> Joseph Torigian: Point well, Xi Jinping and the his relationship with other so called princelings. My understanding is that it's somewhat fraught, right?

So I think that it's now harder for senior figures to promote their children than it was in the past. And even in the past when they did it, it was still very deeply unpopular and costly for the party's reputation. In this kind of system, you need to be clever right?

And Xi Jinping is a good example of this, because nobody really knew what he thought until he became the top leader. And so he was ambitious, but it was a careful ambition. So again, to refer to. To Li Ray, he met with xi Jinping in 2002 after a big promotion that Xi Jinping won and said, you know, you should speak out more, your position is different.

And Xi Jinping said, no, I don't know how to do it like you, you know how to hit the ping pong, just so it hits the edge without going over. So in that sense, you. The way to rise in this kind of system is to get a good sense of what the top leader wants and doing it better than anyone else, while also not completely screwing up whatever it is that you are tasked with.

So, so in that sense, the rise to power is a little bit different in China than it is in other places, I think, at least now and then.

>> Bill Whalen: Finally you mentioned that Xi Jinping, I don't want to call it cautious leadership, but you suggest it's a measured leadership, especially in terms of dealing with the Catholic Church, for example.

This generation and the next generation, I assume, may avoid big sweeping things like the Cultural Revolution. Do you think that's the case?

>> Joseph Torigian: You know, it's interesting. Xi Jinping is someone whose life was two lessons in one way. One is what happens when you care about ideology too much and what happens when you don't care about ideology enough.

And it gets to a philosophical question, which is what kind of suffering inspires you, toughens you, dedicates you, and what kind of suffering is a turn off and pushes you away? And Xi Jinping, his ambitions are quite breathless when you really look at what he says he's trying to do, which is to break the cycle of one dynasty collapsing after another by taking 5,000 years of Chinese traditional culture and baptizing it in the legacy of the revolution, what he calls self revolution, which means inspiring people with the story of the Party as moral education.

But the story of the Party is one of suffering, right? It's one of putting the nation's interests first, the Party's interests first. And I can see how for many young Chinese people, that is something that is meaningful, right? But for other Chinese, maybe they don't want to go on the merry go round again.

And I think this is something Xi Jinping really worries about, right, because the revolution toughened the first generation, the Cultural Revolution toughened the second generation, or at least the toughened Xi Jinping. But how do you toughen the third generation in a way that's effective and that's something they're trying to figure out.

And one way they do that is by talking about Party history. And if you read my book, you actually See that they did a lot of things wrong. And so that's also something that's effective but also problematic.

>> Bill Whalen: And it really is a great book. Final question for you, Joseph.

If I could get you 10 minutes of FaceTime with Xi Jinping, what would you ask him?

>> Joseph Torigian: I'd ask him if he read my book, maybe I've reflected on this so much that I don't even really know where to start. Right, I think that probably I would ask him about June 4, 1989, whether he was communicating with his father during those days and what his father was saying.

>> Bill Whalen: It's a question to ponder because you get only a few minutes of the leader, and you see this happen in American politics all the time. If they don't like the question, what do they do? They don't answer it. They run out the clock,

>> Joseph Torigian: you know? Yeah, I interviewed the Dalai Lama from my book, and it wasn't.

Yeah. And it was very challenging, right, Because I felt this burden of being one of the few people who had looked at the material, both in Chinese, but I also had a lot of Tibetan materials translated. And I had interviewed Tibetan people who had interacted with Xi Zhongshen and his secretaries counseled me.

They told me how to go about it, and they gave me all of these suggestions. But, you know, how you phrase the questions to get a good answer and how you.

>> Bill Whalen: Not to get away a state secret here but how do you reach the Dalai Lama? I assume he's not@lamail.com, how do you find him?

>> Joseph Torigian: When I once I did get in touch with one of his secretaries, it took me years to actually schedule a meeting because he's so busy. But on the other hand, I think the Dalai Lama and the people around him recognize that outreach to people is essential for them to get their message out.

Now, at the same time, it's interesting, like, I didn't get the sense that they were trying to curate for me my interactions with him for a political purpose. I was actually quite impressed by his secretaries, by the sense that I did get the sense that they wanted me to get what was useful for me to tell the historical story.

Right. Which I found quite meaningful, actually, to be honest with you.

>> Bill Whalen: And I apologize. I cut off the rest of what you're gonna say about your time at Xi Jinping.

>> Joseph Torigian: I'd have to go back and reflect, because you're right, which is you have what you really want to ask, but then you have to figure out how to ask it.

And to be honest, to be Frank with you. I would love to speak with the, I didn't write this book to. With any particular political purpose in mind. I wrote it, for one, because I think that there is an inherent value to doing good history and that it doesn't need an instrumentality.

I wrote it because I thought that the people's lives deserved to be told. Right. And also because I thought that people needed to know how the Chinese Communist Party works. And so I have my own views. But the purpose of the book was to facilitate a conversation. And to the extent that he or anyone else in the party would want to be a part of, that is something that, of course, I would always be open to.

>> Bill Whalen: Are you going to write a bio on him at some point?

>> Joseph Torigian: I'm not planning on it right now. I won't say I will never do it, but that's not in the cards in the immediate future.

>> Bill Whalen: Okay. By the way, I think the worst question ever asked to the Dalai Lama was, has he ever seen Caddyshack?

>> Joseph Torigian: Did somebody really ask him that?

>> Bill Whalen: Someone actually asked at one point, has he seen the movie Caddyshack?

>> Joseph Torigian: Wow. We'll have to look that up.

>> Bill Whalen: Yeah,

>> Joseph Torigian: yeah, I didn't ask him that. Hopefully my questions were. Maybe it would have loosened them up, maybe it would have facilitated a more, a better conversation, but you never know.

>> Bill Whalen: Exactly Joseph, great conversation. I neglected to mention the introduction that you're actually back in Michigan. Why you have left Palo Alto in the summertime. It's 70 degrees here today, my friend, so.

>> Joseph Torigian: Well, you know, this is one of the last things I'll be doing as a research fellow at the Hoover Institution.

And so this is a great coda to the two years that I spent out there. And I do love California, but Detroit is still home. So I'll be spending the last month of the summer back here.

>> Bill Whalen: Okay, well, thanks for all the great work, and I hope you enjoy your time at the history Working lab.

And it really is a great thing that Kotkin and Neil Ferguson and Victor Davis Hansen have cooked up.

>> Joseph Torigian: It's a wonderful program. And the book would not have been the book if I hadn't had that time and space and access to the archives. And so I'm very grateful to Steve for having me at the lab.

>> Bill Whalen: Okay, Joseph, great conversation. Thanks for joining us today.

>> Joseph Torigian: Thank you.

>> Bill Whalen: You've been listening to matters of policy and politics. Hoover Institution podcast devoted to governance and balance and power here in America and around the globe. If you've been enjoying this podcast, please don't forget to rate, review and subscribe to our show.

If you wouldn't mind, please spread the word. Tell your friends about us. The Hoover Institution has Facebook, Instagram, and X feeds. Our X handle is hoverinst that's spelled H-O-O-V-E-R-I-N-S-T. Joseph Tyrigian is on X as well. His X handle is @Josephtorighian, let me spell that for you. J-O-S-E-P-H-T-O-R-I-G-I-A-N at Joseph Turingian, his book, by the Way, the Party's Interests Come first, the Life of Xi Zhongshen thank you, Father Xi Jinping.

I mentioned our website at the beginning of the show, which is hoover.org. While you're there, sign up for the Hoover Daily Report, which keeps you abreast of the latest that Hoover Institution fellows are doing. And that comes to your inbox weekdays for the Hoover Institution, this is Bill Whalen, we'll be back soon with another installment of Matters of Policy and Politics.

Till then, take care. Thanks for listening.

>> Speaker 3: This podcast is a production of the Hoover Institution, where we generate and promote ideas advancing freedom. For more information about our work, to hear more of our podcasts, or view our video content, please visit hoover.org.