The author, a brigadier general in the Israel Defense Forces, is a contributor to the Hoover Institution’s Middle East and the Islamic World Working Group. He is the commander of the Dado Center for Interdisciplinary Military Studies.

World order as we have known it since the collapse of the Soviet Union is rapidly changing for the worse. Commentaries link that change with the emergence of Chinese economy and ambition, the rise of Russian nationalism, the decline of nation-states and the Arab states in particular, and more. But the defense community cannot escape the fact that a significant part of that worsening global order should be attributed to the decline of Western military deterrence. That decline is due not only to insufficient investments but even more so to the rapid erosion of Western military supremacy.

The pressing question the defense community faces is what can be done, from our perspective, to affect change in these realities.

Creative destruction

Much has been written and discussed about military change and the use of emerging technologies. Technology is in fact dominant in the creation of military capabilities, but we tend to view it in isolation. Two well-known cases of military disruption from the early years of World War II offer a reminder that in both force employment and force generation, an accurate and focused approach to using that technology is also indispensable.

Part of Germany’s overwhelming success, at least in the initial phases of the Second World War, had to do not with technological superiority but with a more accurate application of capabilities to solve a specific problem. French planners, reviewing the lessons of the Great War, considered the power of artillery to be the dominating force in war, but the Wehrmacht viewed that belief not as an unassailable fact but as a problem to be solved. German forces harnessed established technologies of the time—rapid motorized transport and radio—to enhance their ability to maneuver. The Maginot Line and the slow command-and-control structure of the Anglo-French defenders were overwhelmed. In a second arena, war at sea, the German navy was inferior to that of Britain, with its mighty fleet. But the Kriegsmarine was reasonably quick to adapt and shift to submarine warfare, which for a time was devastatingly successful. Germany solved its naval deficit through a strategy of blockading Britain, using area-denial asymmetric tactics.

How focused are war planners today, competing for technological superiority? Numbers of troops, weapons, and equipment are essential, as is superior technology, but these are not the whole story. We need a theoretical framework. What is the great problem we are trying to solve?

Strategy transformed

When Russia’s initial offensive in Ukraine failed in February-March 2022, most analysts were taken by surprise. Putting aside poor Russian performance in chain of command and logistics as well as Ukrainian will and resilience—all true—what we witnessed that winter in Ukraine was the prevalence of munitions over maneuver. Putting an end to any prospect of rapid long movements, so-called ranged fires made the war a huge artillery duel: attrition warfare with few, and very costly, movements on the battlefield.

The second Nagorno-Karabakh war of 2020, involving Armenia and Azerbaijan, provides another example of the evolution in combat. Unmanned air surveillance, targeting, loitering munitions, and other forms of accurate long-range weapons swept Armenia’s largely mechanized forces off the battlefield. The famous fighting quality of the Armenian forces was no match for the modern targeting-and-strike system deployed by their adversaries.

In Yemen, Houthi forces also have successfully used such capabilities, provided by Iran, to deter the Saudi-led coalition from continuing and escalating the war there. The Houthi forces had good teachers: the Lebanese Hezbollah (HL). Fighting the HL in the war of 2006, Israeli defense forces proved ineffective at stopping rockets fired at Israel’s home front. At the same time, they also proved to be vulnerable to modern anti-tank missiles like the Russian Kornet. Since then, Israel seems to have given up its traditional direct approach to defense and is as much deterred by the HL as it is deterring it.

Contested domains, a widely used term, refers to a variety of contemporary military challenges that include cyberwar, electromagnetic measures, and space. But although these do matter, the one decisive element in battle is ranged fires. Accurate ranged fires, integrated with targeting capabilities, simply enable a regional power to deter a global one. In some cases, they enable malign actors to deter legitimate ones. The very thing that made the initial Ukrainian defense a success could work against world order.

The problem

Accurate, effective weapons integrated with intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities are no longer exclusive to Western actors or dominated by them. Those capabilities make it easier for local aggressors to commit abrupt violations of international norms and the status quo and get away. Fire dominance defines the problem for any nation that seeks to deploy its forces to uphold international norms and remove threats.

The next step

To return for a moment to the twentieth century, one is tempted to describe military transformation between the world wars as an endless list of technologies and capabilities, with the German development of Blitzkrieg, mentioned above, a prominent example. Blitzkrieg exploited technology to regain battlefield maneuverability in the face of industrialized firepower—utilizing the second industrial revolution, built upon the internal combustion engine, to overcome the military consequences of the previous one.

But I suggest that just like some of the interwar and World War II militaries, we are spending much of our resources, including cutting-edge technology, improving legacy theories and concepts of war. In the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), for example, artificial intelligence and other emerging technologies are put to work mainly to enhance the performance of intelligence gathering and processing, the heart of the IDF’s targeting machine. While the results are significant for targeting, the improvements are still no match for the enemy’s skill in concealment and redundancy. As cyberwar and electromagnetic and information warfare take their place in domain doctrines, the enemy’s fires seem to remain largely untouched.

From a broad perspective, one can look at modern warfare as a history of fire dominance versus maneuver dominance. Platform-centric thinking in today’s armed services means that most responses to the problem of accurate fire are focusing on protecting those platforms. Those efforts have exhausted themselves. Our targeting kill-chains are just not complete and fast enough to prevent enemy long-range fires from getting through. Modern force-protection is also insufficient. All single lines of defense are usually breached. As two defense experts write, “There are simply not enough interceptors to sit and play catch.”

There is another path, yet to be exploited: regain maneuverability and at the same time render enemy resistance irrelevant by suppressing enemy fires at their source.

Wisdom beyond tech

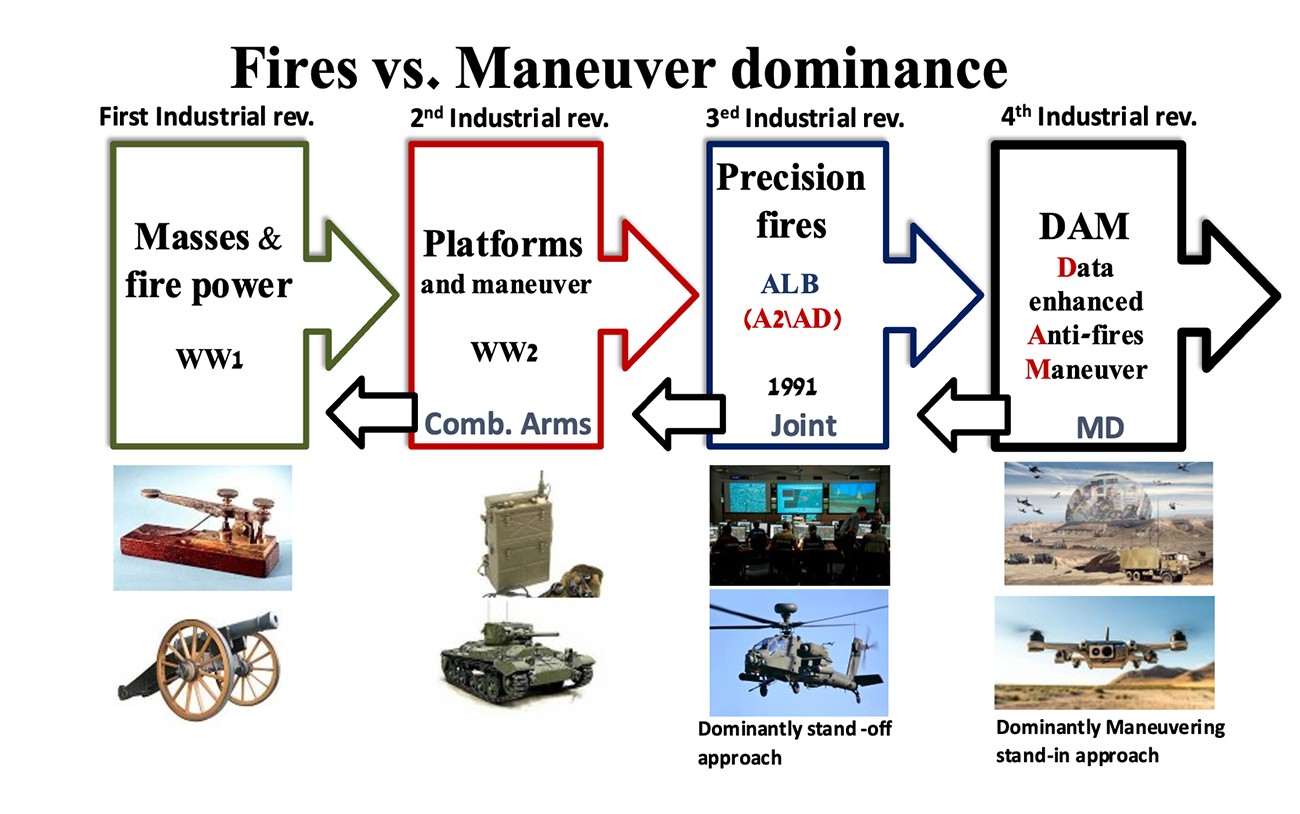

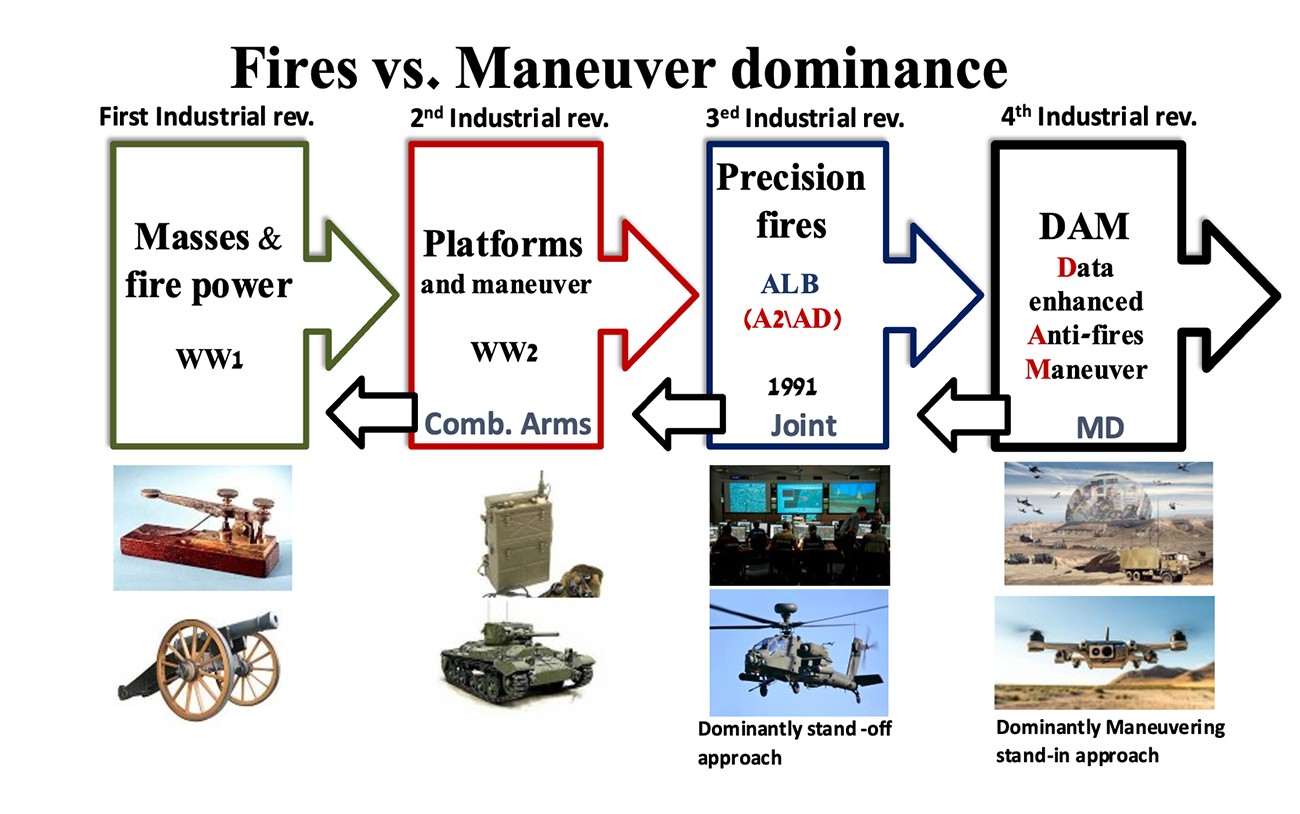

This chart shows key developments in the tools and weapons of warfare:

The first industrial revolution in warfare involved steam power and machine guns, as in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–5. It was characterized by mass armies and mass slaughter. The second industrial revolution pulled away from mass attacks and honed ideas of maneuver; it introduced the internal-combustion engine, radio, and combined arms and command, especially of armor and air power. Engines and radios were essentially better versions of the older tech. The third industrial revolution brought computers and networks for the targeting of platforms, but battlespace awareness in these new “joint” realms arose only where many people could work behind many computers. And all three industrial eras had large bureaucracies committed to the way things were.

The key today is to fully exploit the fourth industrial revolution, automated and miniature networked components, to successfully target the fires themselves. “Sensor to shooter” networks should be the leaping factor that allows the targeting of ascending projectiles and the quick strike at the fire sources even as they try to disperse. This network of digital artillery radars and aerial reconnaissance assets would be effective only at close ranges, forcing us to readapt from our customary “stand off” set of mind. If developed and employed correctly, it would monitor a wide battlespace and slash response time; artillery pieces, anti-tank and anti-air missile teams, and others could be located and hit in less than a minute. Multiple-barrel rocket systems could be struck while they were still firing. Projectiles could be spotted and intercepted in midflight. The enhanced targeting and strike capabilities will protect not only military forces but also civilian populations.

The fourth industrial revolution’s reliance on automated data processing makes it less dependent on human labor. Military application of it will use mobile data networks empowered by new unmanned aerial and space assets. And, just as with tanks, airplanes, and radios, the military modernization of the fourth industrial age will be stillborn if we fail to take it out of our headquarters and into the tactical level. Enhanced sensing, accuracy, and speed will not be enough unless we get it close to the enemy.

Technology is not a magic solution, of course. Hitler’s obsession with “wonder weapons” in the later stages of World War II attests to that. History also teaches us that technology is not simply to be implemented. Rather, it should make us rethink our way of war. World War I locked generals’ minds in their chateau headquarters, and that habit has proved hard to break. The modernization of the 1990s again collected senior commanders, this time in their digital headquarters. Today, power can and should be shifted to the forces deployed on the ground. They will work within a new envelope of automated air assets, sensors, data processing, fire suppression, and forward-interception capabilities. They will be able to outmaneuver ranged fires while confronting adversaries with a dilemma: fight and be annihilated, or give up. This “Data-enhanced Anti-fires Maneuver” (DAM) concept of operations should become our modern Blitzkrieg.