This essay is based on the paper “The Rise and Fall of Paper Money in Yuan China, 1260–1368” by Hanhui Guan, Nuno Palma, and Meng Wu.

In his famous travelogue, The Travels of Marco Polo (1298), Marco Polo provided one of the earliest western accounts of use of paper money during the Yuan Dynasty under Mongol rule. At a time when most of the world used gold and silver as mediums of exchange, Marco Polo was struck by the fact that a piece of paper, made from the bark of mulberry trees, was universally accepted across the empire as a form of money.

Following this trail, we examine paper money in Yuan China. As the first political regime in history to use a precious metal—silver—to regulate the issuance of paper money, the Yuan government consolidated a previously chaotic monetary system that had included various types of inconvertible paper money, copper coins, and iron coins. In addition, as the first political regime to enforce paper money as the sole legal tender, the Yuan dynasty saw its paper currency proliferate across all levels of society. In public spending, it was used for tax payments, granted as imperial rewards, and disbursed as official salaries. In private transactions, people could use paper money to purchase a wide range of goods and services.

To understand how the first precious metal standard operated under an imperial regime, we conduct extensive research based on a wealth of primary and secondary sources. Empirical analysis of these sources enables us to explore the evolution of the Yuan’s paper money system, examine the relationship between paper money issuance and the government’s fiscal constraints, and investigate the factors that correlated with the overissuance of currency, ultimately leading to hyperinflation as the dynasty collapsed.

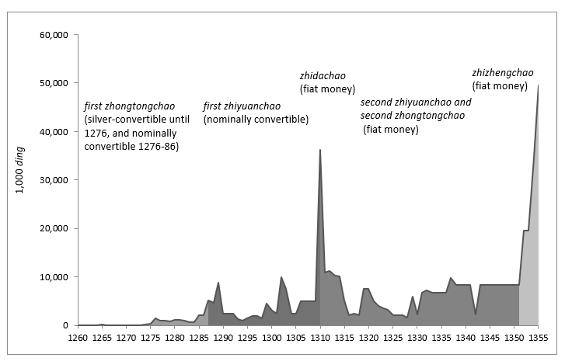

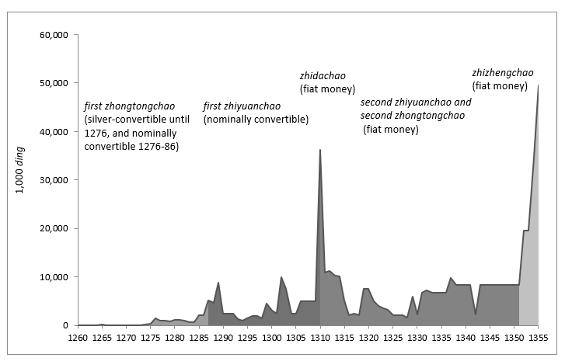

As seen in figure 1, the Yuan government issued five distinct types of paper money throughout the regime: zhongtongchao 中統鈔 (1260–86), first zhiyuanchao 至元鈔 (1287–1309), zhidachao 至大鈔 (1310), second zhiyuanchao (1311–51), and zhizhengchao 至正鈔 (1352–68). Except for zhidachao, which circulated for only a year and was withdrawn from the market due to political reasons, other paper currencies circulated for a period of two to three decades. In most cases, the issuance of new money was a result of the depreciation of existing currencies. In addition, as the figure illustrates—with the exception of zhidachao and zhizhengchao—paper currencies were issued at a moderate level.

Note: The Yuan government used the ding as the unit of account and regulated that 1 ding was equal to 50 guan Zhongtongchao. Although the government issued various monies, it used Zhongtongchao to record fiscal revenues and expenditures. Other paper monies have been converted to Zhongtongchao based on their exchange rates.

Sources: Yuanshi 元史 (History of the Yuan), Song Lian宋濂 (Beijing, 1976), chapters 35, 36, 39, 42 to 44, and 93 to 95; Liu, Sen劉森, “Yuandai chaoben chutan 元代鈔本初探 (Preliminary study of the money reserves in the Yuan Dynasty)”, Journal of Henan University (Social Science), 2, (2007), pp. 142–3.

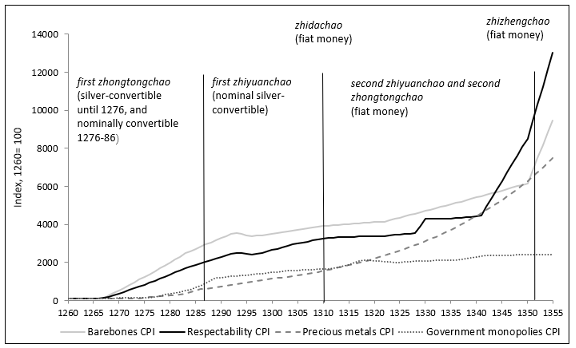

To assess the price stability, we construct four price indexes: a barebones Consumer Price Index (CPI), a respectability CPI, a government monopolies CPI, and a precious metals CPI (see fig. 2). These indices are based on multiple observations for twelve products, including rice, millet, cotton, salt, silk, horses, gold, silver, and tea. When dividing the entire period into three subperiods (1260–90, 1290–1340, and 1340–55) we find that the corresponding inflation rates were 4.5 percent, 1.8 percent, and 11 percent, as measured by the respectability CPI. This indicates that with the exception of the last two decades, which saw hyperinflation, the price level remained relatively stable for over half a century.

Source: Our calculations are based on the underlying data collected by Chunyuan李春圓, “Yuandai de wujia he caishui zhid元代的物價和財稅製度 (The prices, taxation, and fiscal system in Yuan China)” (PhD thesis, Fudan University, 2014).

We also investigate which factors led the Yuan government to issue paper money by examining the correlations among warfare, imperial grants, natural disasters, and the quantities of paper money issued. Additionally, we look at the role of the silver standard in regulating the issuance of paper money. We find that military pressure, particularly rebellions, generated fiscal demands that led to the overissuance of money. Moreover, military pressure was significantly more likely to increase the issuance of paper money under the fiat standard than during the period of the silver standard.

The Yuan dynasty collapsed in 1368, when the Han Chinese Zhu Yuanzhang established the Ming Empire. Although the Mongols were expelled back to the Mongolian steppe and never returned, their impact on China’s politics, economy, society, and culture remains long-lasting. Among these influences, the most significant one was arguably the official incorporation of silver into China’s monetary system, ushering in a silver economy that shaped the global economic landscape for centuries to come.

Read the full paper here.

Meng Wu is assistant professor in strategy at Manchester Metropolitan University.

This essay is part of the Long-Run Prosperity Research Brief Series. Research briefs highlight research that enhances our understanding of the factors that drive long-run economic growth and examine its policy implications.