- Economics

- US Labor Market

- Contemporary

- World

- Security & Defense

- Terrorism

- US Defense

- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

- Immigration

- History

“A Muslim has no nationality except his belief,” the intellectual godfather of the Islamists, the Egyptian Sayyid Qutb, wrote decades ago. Qutb’s children are everywhere now; they carry the nationalities of foreign lands and plot against them. The Pakistani-born Faisal Shahzad, the failed Times Square bomber, is a devotee of Qutb’s doctrine. Major Nidal Malik Hasan, the Fort Hood shooter, was another.

Qutb was executed by the secular dictatorship of Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1966, but his thoughts and legacy endure. Globalization, the shaking up of continents, the ease of travel, and the doors for immigration flung wide open by Western liberal societies have given Qutb’s worldview greater power and relevance. What can we make of a young man like Shahzad working for Elizabeth Arden, receiving that all-American degree, the MBA, jogging in the evening in Bridgeport, then plotting mass mayhem in Manhattan?

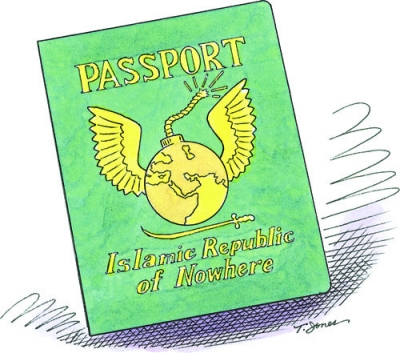

The Islamists are now within the gates. They fled the fires and the failures of the Islamic world but brought the ruin with them. They mock national borders and identities.

A parliamentary report issued by Britain’s House of Commons on the London Underground bombings of July 2005 lays bare this menace and the challenge it poses to a system of open borders and modern citizenship.

The four men who pulled off those brutal attacks, the report noted, “were apparently well integrated into British society.” Three of them were second-generation Britons born in West Yorkshire. The oldest, a thirty-year-old father of a fourteen-month-old infant, “appeared to others as a role model to young people.” One of the four, twenty-two years of age, was a boy of some privilege; he owned a red Mercedes given to him by his father and was given to fashionable hairstyles and designer clothing. This young man played cricket on the eve of the bombings. The next day, the day of the terror, a surveillance camera recorded him in a store. “He buys snacks, quibbles with the cashier over his change, looks directly at the CCTV camera, and leaves,” reads the official investigative report. Two of the four, rather like Faisal Shahzad, had spent time in Pakistan before they pulled off their deed.

A year after the London terror, hitherto tranquil Canada had its own encounter with the new Islamism. A ring of radical Islamists were charged with plotting to attack targets in southern Ontario with fertilizer bombs. A school-bus driver was one of the leaders of these would-be jihadists. A report by the Canadian Security Intelligence Service unintentionally echoed the British House of Commons findings. “These individuals are part of Western society, and their ‘Canadianness’ makes detection more difficult. Increasingly, we are learning of more and more extremists that are homegrown. The implications of this shift are profound.’ ”

UNSETTLING FREEDOM

Indeed they are, but how can “Canadianness” withstand the call of the faith and the obligation of jihad? I think of one Egyptian Islamist in London, a man by the name of Yasser Sirri, who gave the matter away some six years ago: “The whole Arab world was dangerous for me. I went to London,” he observed.

In Egypt, three sentences had been rendered against him: one condemned him to twenty-five years of hard labor, the second to fifteen years, and the third to death for plotting to assassinate a prime minister. Sirri had fled Egypt to Yemen, then to the Sudan. But it was better and easier in bilad al-kufar, the lands of unbelief. There is wealth in the West and there are liberties afforded by an open society.

In an earlier age—I speak here autobiographically, of the 1960s when I made my way to the United States, and not of some vanished world long ago—the world was altogether different. Mass migration from the Islamic world had not begun. The immigrants who turned up in Western lands were few, and they were keen to put the old lands, and their feuds and attachments, behind them. Islam was then a religion of Afro-Asia; it had not yet put down roots in Western Europe and the New World. Air travel was costly and infrequent.

The new lands, too, made their own claims, and the dominant ideology was one of assimilation. The national borders were real, and reflected deep civilizational differences. It was easy to tell where “the East” ended and Western lands began. Postmodernist ideas had not made their appearance. Western guilt had not become an article of faith in the West itself.

Nowadays the Islamic faith is portable. Itinerant preachers and imams transmit its teachings to all corners of the world, and from the safety and plenty of the West they often agitate against the very economic and moral order that sustains them. Satellite television plays its part in this new agitation, and the Islam of the televised preachers is invariably one of fire and damnation. From tranquil, banal places (Dubai and Qatar), satellite television offers an incendiary version of the faith to younger immigrants unsettled by a modern civilization they can neither master nor reject.

And home, the old country, is never far. Pakistani authorities say Shahzad made thirteen visits to Pakistan in the past seven years—an unthinkable feat three or four decades earlier. Shahzad lived on the seam between the old country and the new. The path of citizenship he took gave him the precious gift of a U.S. passport but made no demands of him.

MODERNITY RUNS OFF THE RAILS

From Pakistan comes a profile of Shahzad’s father, a man of high military rank, and of property and standing. He was “a man of modern thinking and of the modern age,” it was said of him in his ancestral village of Mohib Banda. That arc from a secular father to a radicalized son is, in many ways, the arc of Pakistan since its birth as a nation-state six decades ago. The secular parents and the radicalized children are also a tale of Islam, that broken pact with modernity—the mothers who fought to shed the veil and the daughters who now wish to wear the burqa in Paris and Milan.

In its beginnings, the Pakistan of Faisal Shahzad’s parents was animated by the modern ideals of its founder, Muhammad Ali Jinnah. In that vision, Pakistan was to be a state for the Muslims of the subcontinent, but not an Islamic state in the way it ordered its political and cultural life. The bureaucratic and military elites who dominated the state, and defined its culture, were a worldly breed. The British Raj had been their formative culture.

But the world of Pakistan was recast in the 1980s under a zealous and stern military leader, Zia ul-Haq. Zia offered Pakistan Islamization and despotism. He had ridden the jihad in Afghanistan next door to supreme power; he brought the mullahs into the political world, and they, in turn, brought the militants with them.

This was the Pakistan in which young Faisal Shahzad was formed; the world of his parents was irretrievable. The maxim that Pakistan is governed by a trinity—Allah, army, America—gives away this confusion: the young man who would do his best to secure an American education before succumbing to the call of jihad is a man in the grip of a deep identity crisis. The overcrowded cities of Islam—Karachi, Casablanca, Cairo—and those cities in Europe and North America where the Islamic diaspora is now present in force have untold multitudes of men like Faisal Shahzad.

This is a long twilight war, the struggle against radical Islamism. We can’t wish it away. No strategy of winning “hearts and minds,” no great outreach, will bring this struggle to an end. America can’t conciliate these furies. These men of nowhere—Faisal Shahzad, Nidal Malik Hasan, the American-born renegade cleric Anwar Awlaki, now holed up in Yemen, and their likes—are a deadly breed of combatant in this new kind of war. Modernity both attracts and unsettles them. America is at once the object of their dreams and the scapegoat onto which they project their deepest malignancies.