- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- History

- Contemporary

Now that the newly elected South Korean government of Kim Dae-jung has eased travel and investment restrictions toward North Korea, the United States should relax all economic sanctions against North Korea. At one time, it made sense to contain and isolate this regime. Now, nearly a decade after the fall of the Berlin Wall, it makes better sense to lift sanctions against the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea as a means to begin drawing it into the global network.

A sanctions policy must be examined from the vantage point of possible success as well as purpose. North Korea represents a clear case where success is absent and purpose has atrophied. Ending sanctions will signal a new approach and strengthen the hand of younger reformers in Pyongyang.

Along with this pariah state, the United States has sought to contain, isolate, or penalize many other governments. Washington’s weapon of choice has become economic sanctions. Sanctions represent a course of action, short of war or covert action, designed to hit back at a state’s bad behavior. They are easy to implement. They respond to the need to register disapproval but avoid taking a tougher approach. Since 1993, the United States has resorted to unilateral economic sanctions more than sixty times for foreign policy objectives against thirty-five countries (see map on next page).

But this increasingly uniform response may not always be effective in persuading a targeted regime to mend its ways or bring it down. In some instances, suspending economic sanctions (not military ones) will achieve more desirable results.

Economic sanctions are blunt instruments that wreak havoc with an economy. They especially afflict a country’s ordinary citizens, often without affecting the ruling elite. Like mass bombings during World War II, however, economic attacks may rally a beleaguered population to its despot, who points to the United States as the source of its lowered living standards rather than his failed statist policies.

Sanctions have not undermined the despotic rulers in Fidel Castro’s Cuba or Kim Jong-il’s North Korea, both of which have endured tight U.S. economic sanctions since the height of the East-West standoff. The real damage to both—which exist as Stalinesque anomalies in our interdependent, interconnected, and market-driven world—has resulted from the demise of their Soviet patron.

Thus, the case for sanctions in general is weak, although Washington’s toughened sanctions against South Africa in 1986 are often cited as the eventual cause of the white minority’s relinquishing its apartheid policy toward the African majority. Also, embargoes directed at Vietnam’s 1977 invasion of Cambodia are claimed to have persuaded Hanoi to pull out.

Economic attacks may have the unintended consequence of rallying a beleaguered population around its despot.

South Africa’s initial move away from strict racial separation, however, predated the U.S. imposition of tough sanctions. Revulsion against apartheid gradually developed within the Afrikaner community because of African resistance, moral conviction, and sensitivity to international ostracism.

Vietnam also changed policy for a mixture of reasons. Moscow pressured Vietnam because it wanted improved relations with China, which opposed Vietnam’s intrusion into Cambodia. Reformers within Vietnam’s leadership pushed for economic liberalization. The dramatic events in Eastern Europe during 1989–1990 prompted Vietnam to renew normalization efforts with China and cease overt interference in Cambodia.

| U.S. ECONOMIC SANCTIONS: Countries now under U.S. sanction, and the year sanctions were first imposed. | |

|---|---|

|

|

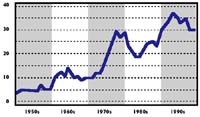

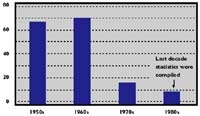

| The number of U.S. sanctions rose until the mid-90s | ...but fewer and fewer had their intended effect. |

TOTAL SANCTIONS IN EFFECT*

|

SUCCESS RATE

|

Sanctions are a short-term bet that pain will lead to change. Economic warfare against Iraq and Yugoslavia, which should be temporarily sustained, is directed at regimes that currently thwart major U.S. policy objectives. Abandoning sanctions against them would be interpreted as a diplomatic retreat. Ending economic sanctions against North Korea would be viewed not as weakness but as the application of a different weapon. Our allies would welcome it, for most oppose embargoes. Washington should coordinate with Seoul in renouncing its sanctions so that South Korea can be seen as a continuing catalyst for change in the status quo on the Korean peninsula.

Economic engagement with a troublesome state, in contrast, is a longer-term strategy. Although we have some sanctions on China, we trade with it to move Beijing away from its centralized economy toward greater democracy, freer markets, and peaceful pursuits. If this policy fails, then we should have the courage to change it. By the same token, U.S. sanctions against North Korea (as well as Cuba) have not brought the regime down for more than four decades and should be replaced by a more effective approach.

Neither foreign investments nor trade will greatly flow to the decrepit DPRK because other states offer economic freedom and prospects for better financial returns. But ceasing economic conflict will remove the United States as a scapegoat for its economic backwardness and can help smooth its eventual integration into the global economy. Otherwise, when communism does expire in North Korea, the United States, as the sole superpower and a major adversary, could face the economic equivalent of a toxic dump. Modest economic growth will lighten our load, help the people of North Korea, and pave the way for a peaceful reunification of the two Koreas.

The chief stumbling block in the stalled four-party talks in Geneva remains the presence of U.S. forces in South Korea. U.S. negotiators want to use the promise of repealing sanctions as a bargaining chip. But throwing this smaller chip to Pyongyang will not weaken the American position. It will serve U.S. and South Korean interests, without compromising our military presence.

Even Seoul is displaying weariness with its bans on contacts between individuals across the demilitarized zone. To unite families separated by the war and the cold peace, Seoul recently amended national security laws so its citizens can send small amounts of money directly to relatives across the DMZ.

Economic sanctions are a short-term bet that pain will lead to change. It rarely does.

Even the thinnest wedge into repressive societies can help pry them open. Dooming the Soviet Union to the dustbin of history resulted, in part, from contact with Western society. It’s time to expose North Korea to similar winds of change.