- Security & Defense

- Middle East

- Determining America's Role in the World

America’s view of the Middle East has been too terrestrial and too militarized for too long. That is understandable, as images from Desert Storm and wars in Afghanistan and Iraq are recurring touchstones. The war in Gaza has reinforced those perspectives. However, as we look to the region’s future, we must look seaward.

For the first time in decades, there is a glimmer of a more seaward, or maritime, perspective. The Trump administration’s national security and defense strategies should be released in the coming months. Although budget requests should follow strategy, the recently signed executive order aiming to restore America’s maritime dominance, significant maritime-related budget pronouncements, and noteworthy Congressional alignment bode well. Hopefully, the Trump strategies, when published, will thoughtfully and forcefully articulate renewed American maritime imperatives and interests.

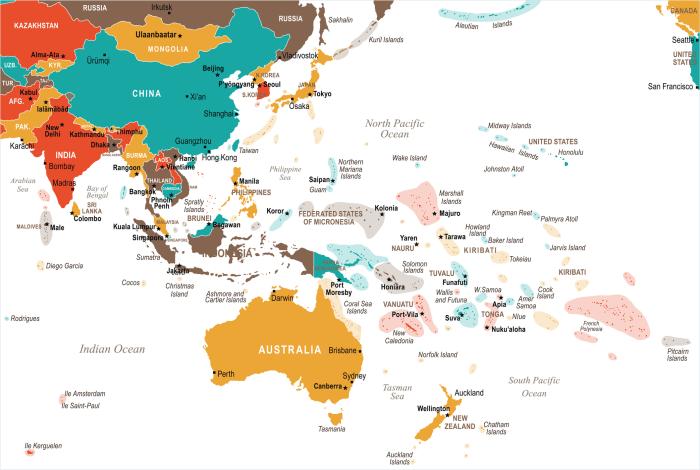

The strategies’ focus will surely be on the Indo-Pacific, with the Western Pacific and countering China garnering top billing. Europe will be deemphasized, although a nod to the importance of the Arctic's opening will likely be included. However, any call for less maritime presence in the Middle East to enable more attention to the Indo-Pacific should not be rushed. For decades, that has been a desire. However, neglecting the maritime Middle East will be a significant shortcoming in any security, defense, or maritime strategy. The maritime Middle East, particularly the maritime Indo-Middle East, will grow in strategic importance in the coming years.

The maritime Middle East is extensive and complex, both physically and in terms of its commercial and political aspects. The Gulf War introduced Americans to the Persian Gulf and the critical Strait of Hormuz. Then, those were the only maritime aspects of the Middle East that mattered. Recent events brought more of the maritime Middle East to the fore, with Houthi attacks on shipping in the southern Red Sea and the defense of Israel being augmented by ships in the Eastern Mediterranean. Those geographies frame some of the contours of the maritime Middle East, but not completely. Nor do those locations and military actions capture the critical commercial linkages that will define the region’s future strategic importance.

The maritime Middle East, from the Eastern Mediterranean to the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, Persian Gulf, the Arabian Sea, and including the Black Sea, is the maritime hub of Eurasia and the Indo-Middle East-Africa nexus. The opening of Arctic Sea lanes and trans-Eurasian rail routes will be increasingly touted as the essential Eurasian east-west commercial transportation routes. Still, the Indo-Middle East maritime link will dominate. Middle East energy resources will remain crucial to Eurasian economies, particularly for the region's energy producers. Africa's sought-after mineral resources will flow by sea to India and China, through the Suez Canal to Europe, and points westward. Although the terrestrial portion of the envisioned India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) winds predominantly through the Arabian Peninsula, its bookends are the east and west boundaries of the maritime Middle East.

The U.S. view of the maritime Middle East must start with a different lens. Our reliance on the singular naval long glass of today must be replaced with a wider-angle lens that centers on commercial interests unfolding in the broader region. To be sure, naval forces will play a role, but as throughout history, navies are fundamentally about protecting and expanding commercial interests. That is how we must think about the future.

The commercial nature of the maritime Middle East is not new. Centuries ago, Arab traders plied the waters of the region, reaching out to Southeast Asia and the west coast of Africa. Although not as extensive nor enduring as the voyages of Arab merchants, Beijing, too, claims historic maritime legitimacy based on the treasure voyages of Admiral Zheng He between 1405 and 1433 throughout the Indian Ocean as far as East Africa. The very sea lanes of centuries past remain crucial to conveying the riches of our time. Critical mineral outflows of Africa and the manufacturers in South Asia, Southeast Asia, and Northeast Asia, as well as those in China, will continue to move inputs and outputs along the region's sea lanes. China had a prescient commercial lens three decades ago, hence the Maritime Silk Road component of its Belt and Road Initiative. Although late to the game, the current lean toward ‘restoring America’s maritime dominance’ can and should be the foundation for repositioning the U.S. in the region. Boldly calling for a renewal of domestic shipbuilding, modernizing our Merchant Marine, and revitalizing our maritime workforce, the Trump maritime initiative is importantly grounded in a commercial, rather than solely a naval foundation.

India’s manufacturing growth, investments in Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states, and IMEC portend significant growth in regional maritime and coastal infrastructure. The U.S. must not forego these commercial maritime opportunities. Projects, whether unilateral or cooperative, can stimulate the broader U.S. maritime industry. Regional maritime states need maritime infrastructure and logistic networks. They will get them where they can. For the U.S. to be on the sidelines is an invitation for others to fill the vacuum, as we’ve seen before. As the U.S. was preoccupied with naval-gazing, Beijing deftly played the commercial cards of shipping, shipbuilding, and dominating commercial ports globally. To regain maritime standing, the U.S. plan for maritime rejuvenation must go beyond domestic initiatives and activities. Compatible and complementary Indo-Middle East nodes and cargo revenues must be in the plan to give purpose to a larger commercial fleet and maritime workforce. Ship counts and investment numbers garner soundbites; what ships and ports do is what matters.

Although the foundation for the maritime Middle East rests on commercial interests, as had been the case throughout history, relevant naval power and presence are essential to safeguard them. Regardless of the naval emphasis in the western Pacific, it has been in the Eurasian maritime hub where future dimensions of naval warfare have emerged. Ukraine’s Black Sea campaign has been at the forefront of rapid lethal innovation. Similarly, Iran’s Houthi proxy has altered the challenges and means of protecting sea lanes. The varied geography of the region and its extensive littoral environment, whether the eastern Mediterranean, the Red Sea, or the Persian Gulf, will continue to see changes in naval warfare. The region is likely to be the epicenter of evolving unmanned offensive and defense systems in all dimensions - air, surface, and subsurface. Notable purveyors of capable and proven systems are of the region - Iran, Türkiye, and Russia.

Accordingly, assurance of the Middle East’s sea lanes has taken on a new dimension of naval warfare. Legacy platforms and weapons will remain relevant, as seen in the lengthy regional deployments of missile defense destroyers and aircraft carriers, the latter serving fortuitously as movable U.S. sovereign airfields. However, very stressful, smaller, and more numerous threats will emerge. Countering them requires a cooperative and coordinated approach.

Russia and Iran are the unhelpful mix in the unmanned petri dish. Both bruised in recent conflicts, they will strive to rise again by supporting each other and marketing their wares to those who wish to disrupt. The Gulf states, Saudi Arabia, and Europe must move quickly to develop countermeasures in anticipation of that malign effort. For littoral states, defense planning must be forward-looking. The underwater dimension of small, lethal drones has not yet emerged as a significant threat to critical seabed infrastructure, including energy-related facilities, seabed communications cables, or essential water desalination complexes. Time is short. This underwater threat is more acute than has been seen in the Red Sea targeting of individual ships, as entire population centers and ecosystems will be at risk as underwater vehicles mature and proliferate.

Defending sea lanes is a multinational obligation, and protecting coastal infrastructure is optimized by multinational coordination and cooperation. Although several nations are involved in defending ships in the Red Sea, fewer than a handful can engage in kinetic operations. Political considerations are, of course, in play, but few have fielded systems capable of defeating the threats of today, much less those on the horizon above and below the sea. While Europe will have a new focus on land and air capabilities and capacity, it must step up in the defense of vital sea lanes leading to the Suez Canal from the south and the Eastern Mediterranean approaches. Egypt, too, must undertake a new naval expansion in the Red Sea to ensure unhindered flow through the Suez to assure revenue from the Canal.

We are on the cusp of a changed Middle East. A Middle East that, once again, after centuries, looks seaward, whether from the shores of the Eastern Mediterranean or onto the gulfs and seas that adjoin the great Indian Ocean. The new look should be the catalyst for a cooperative regional, indeed global, approach to future commercial opportunities and the supporting naval obligation to safeguard them. The U.S. must not withdraw from the Middle East; it must reset. It must reassert itself in the region commercially and use those opportunities to enhance a necessary and renewed maritime ambition; to see the Middle East not as in the past, but as the Indo-Middle East, the maritime hub of Eurasia; and to view it as pivotal geography, not left to others to shape and dominate.