- International Affairs

American headlines reporting the results from this spring’s British national election focused on Prime Minister Tony Blair’s historic third straight victory. But the accompanying articles often failed to explain that Blair’s Labour Party won not because of Blair’s personal popularity (as in 1997 and 2001) but in spite of him. In fact, all three of Britain’s main political parties emerged from the election unhappy.

Labour lost about a hundred seats off its majority in the House of Commons and managed just 37 percent of the vote, the lowest percentage for a winning party in memory. Accordingly, most Labour members of Parliament (MPs) regard Blair as an electoral liability and hope he will not keep his promise to finish his third term but will instead turn Labour’s leadership over to his Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gordon Brown.

Although the Conservatives gained 33 seats in the House of Commons, they are unhappy because for the second straight election they managed to add no more than a single percentage point to their painfully low total of the popular vote. At 33 percent, they are still far below what they need to put themselves back into serious competition for a return to office by the next election.

Britain’s third party, the Liberal Democrats, actually did much better than the two big parties, adding 5 percent to their vote total and 11 seats for a total of 62, their highest number of MPs in 80 years. But even the Lib-Dems were disappointed because they failed to make up serious ground on the Conservatives and accomplish their ultimate goal: to supplant the Conservatives as Britain’s main opposition to Labour. Although they were pleased to gain 11 seats, they had expected to gain 25 or more.

Apathy and Discontent

This across-the-board disappointment followed a very cranky campaign. Voters everywhere complained that the campaign was negative and personal and that the main political parties were boring to boot. This continued what has been a long period of disenchantment with the two main national parties. In the first two decades after World War II, Labour and the Conservatives won about 90 percent of the total vote, leaving 10 percent to mostly regional parties such as in Northern Ireland. Then, as the British economy fell into a pattern of repeated crises in the 1960s and 1970s and the Scottish and Welsh regional parties became more important, that figure fell to 80 percent. This time (2005) the Labour and Conservative Parties together won only about 70 percent of the vote (leaving the remaining 30 percent divided between the Liberal Democrats’ 22 percent and the regional parties in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland).

When this trend first appeared during the mid-1970s, most analysts thought that the failure of the two main parties to deal successfully with Britain’s economic crisis was driving voters away. But today Britain’s economy is in fine shape and yet voter desertions continue to grow. In the 2005 election, two situations encouraged this trend. First there was strong Labour anger at Tony Blair and his “New Labour” policies, especially his policy on Iraq. As a result many Labour voters either stayed home or voted for the Liberal Democrats. Second was the failure of the Conservatives to broaden their electoral attractiveness. They failed to look like a viable alternative to Labour for the third election in a row. Instead they looked like an upper-class whites-only party that didn’t care very much about reaching out to floating voters. Their leader, Michael Howard, certainly energized his base, but the Conservatives picked off few voters outside that small circle.

Apathy was another characteristic of the 2005 election. Many voters figured that Labour would win without much of a contest. Turnouts for candidate appearances, whether in multiparty debates or individually, were down sharply from the past. Viewer attention to the parties’ political advertisements on television declined, and candidates also reported that they found it more difficult to engage voters in shopping centers and train stations and in house-to-house campaigning.

Ironically some of this apathy may be the result of important policy successes. The economy, which had been at the top of Britain’s worry list for a century, is now in comparatively great shape. Labour certainly made this point a keystone of its campaign. Although the economic revival began during Mrs. Thatcher’s time as prime minister, Labour now gets most of the credit for recent prosperity. Even so, it looked at times during the campaign as though the electorate was willing to say “who cares” about Labour’s economic success if it could find an attractive alternative to get excited about.

The voters in the 2005 election focused elsewhere, on hot-button emotional discontents: immigration and asylum seekers, crime, public services, and the Iraq war. Interestingly, the Conservatives actually used anger about the war to some political advantage, even though as a party they were far more loyal to Blair on Iraq than was his own party. The Conservatives tried to take advantage of a clear side effect of the war: anti-foreign and anti-immigrant feelings, which are running high in Britain. Strong feelings against the European Union and scrapping the British pound in favor of the euro added to these feelings. In the end, though, those issues did not help Howard and the Conservatives very much. Although many Labour voters believed that the Conservatives would be tougher on immigration and asylum seekers, they didn’t accept that the Conservatives had better ideas or leaders.

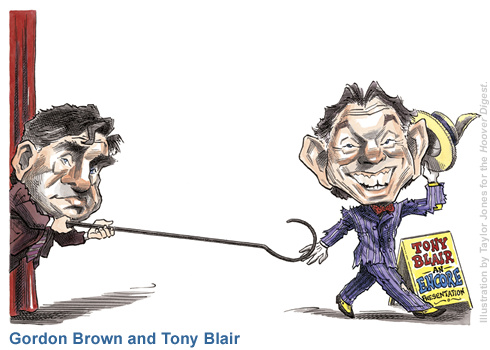

Time for Tony to Go?

Tony Blair’s remarkably long run as a popular prime minister is clearly at an end. Few of his predecessors have done as well, and there is little doubt that Blair was Labour’s most important asset in both the 1997 and 2001 elections. This was due in large part to Blair’s charismatic personality and skills of persuasion but also to his stewardship of Labour’s dramatic organizational and philosophical reformation—styled as “New Labour”—leading up to the 1997 election. Also, Labour’s economic successes banished the argument Mrs. Thatcher had used successfully against Labour for years: that the party could not be trusted on the economy.

But the electorate sent Blair a strong message with the campaign of the 2005 election and its outcome. Labour candidates literally feared that the prime minister would appear in their constituencies to campaign with them.

More than half of Labour’s candidates produced election literature that did not mention Blair or include a photo of him. This was in marked contrast to the previous two elections, when nearly every Labour candidate included a joint picture with Blair for all the constituent voters to see and admire.

In public opinion polls fully three-fourths of the British electorate indicated that they did not trust or respect the prime minister—a record poor percentage. Most Labour voters viewed Blair as a liability and were eager for him to resign.

Some even hoped that he would quit before the election in order to allow the party to elect Gordon Brown, Blair’s increasingly popular chancellor of the exchequer and his partner in rebuilding the Labour Party. In fact, those same polls reported that if Brown had headed Labour in the 2005 election, the party would have won a 10 percent greater share of the vote and would have maintained its huge majority in the House of Commons.

Blair’s deep unpopularity flows in the main from his unwavering support for President Bush’s Iraq policy, especially his strong and unflinching commitment of British troops to the war, followed by his insistence that Britain would stay the course in Iraq despite the damaging post-war insurgency. (Even before the war, Blair had been in some trouble with his Labour colleagues, his domestic policies provoking charges that he was more of a Thatcherite Conservative than a true Labour prime minister.) But Iraq was the “tar baby” for Blair because he never could make a credible and compelling case for taking Britain to war. Throughout the campaign Blair tried to meet the Iraq issue head-on in an effort to win back crucial Labour Party voters, an effort he failed in. But his joint appearances with Gordon Brown, in a brave show of solidarity and celebration of the good economy, helped convince enough Labour voters to stay with the party on election day. As with Bill Clinton’s 1992 presidential slogan, “It’s the economy, stupid,” that show may have saved Labour in the end, but Blair emerged disparagingly regarded as “phony Tony.”

What Next?

The big question at the moment is how long Tony Blair will continue as Labour leader and thus as prime minister. Blair has taken the unusual step in British politics of announcing his plans to retire, insisting that he will complete his current (third) term but not lead his party into a fourth election. Although Americans are familiar with lame-duck presidents who seem to lose political clout with each passing day, British prime ministers have historically preserved their leverage by not addressing their future until an election was imminent or unless they intended to resign immediately.

In setting out his plans Tony Blair has ensured that all eyes in the Labour Party will inevitably be on the contest for his replacement—the more so because many of his colleagues want him to leave well before the end of his current term. Many observers believe that Blair took this approach in his third term to keep party discipline and to refocus Labour’s efforts on accomplishing a record on which the party can successfully run for a fourth term under a new leader. But Blair may not have taken into account the dangers of being a lame duck. Labour’s anti-Blair forces in the House of Commons are likely to seize the dubious advantage of a much smaller majority in order to put pressure on the prime minister by staging strategic voting rebellions that will put Blair’s policy agenda at risk. Given the mood within Labour at the end of the recent election, there is every likelihood that Blair will soon be reminiscing with affection about the time when he had a 167-seat majority that left his internal Labour opponents mostly ineffective. Now he has a majority of just 65 seats, of whom about 50 are Labour “rebels” who are pledged to get rid of him.

But the discussion about Blair’s lame-duck status doesn’t end there because a further complication is nipping at the prime minister: the Labour Party has all but anointed Gordon Brown as Blair’s successor. Brown’s enormous role in Labour’s election victory and his successful stewardship of Britain’s economy have given him a clear lead in the coming Labour leadership competition. Furthermore, the long history of friction between Brown and Blair, especially Brown’s growing impatience with Blair’s unwillingness to step aside, adds a clear marker around which those calling for Blair to resign can rally. Indeed, during the final weeks of the campaign senior Labour officials talked incessantly among themselves about how they were now sending Brown copies of “everything” they were sending to Blair, as if it would be only a short time after the election that Brown would become party leader and prime minister (no new election would be necessary if Blair resigned because Labour would still have a majority of seats).

The Conservative Party also faces important changes. Michael Howard shocked his party the day after the election by announcing that he would resign after a new leadership selection process was in place, before the end of this year. He thus triggered what is rapidly becoming a contentious and divisive leadership struggle for the fourth time in the last eight years. But more than that, the Conservatives are increasingly nervous as they analyze the election results and try to broaden their appeals to the electorate. That they added only 2 percent to their popular vote over the last two elections massively overshadows any joy they feel about adding 33 seats to their number in the House of Commons. The Conservatives have become chronic election losers and are clearly not trusted by the electorate. The Conservatives face a particularly difficult challenge because it is not clear what they could do to win back public confidence. After Labour was crushed in the 1992 election, Blair and Brown correctly saw that Labour needed to accept a large portion of the Thatcher revolution and move Labour toward the center, while beating back the voices from the party’s left wing. This successful strategy led to Labour’s three straight election victories and has left the Conservatives will little room to operate among the electorate. The Conservatives have certainly reorganized themselves to try to be a more inclusive political party and have likewise tried to restrain the more strident voices on their right wing, but they have not been able to reformulate their policy agenda to make it attractive to voters. A major difficulty is that they have lost their traditional dominance on the issue of economic competence: Labour has now grabbed that title. The Conservatives seem stuck with the lowest-common-denominator approach of making themselves “friendlier” and “younger,” while waiting for Labour to become as geriatrically unattractive as the last Conservative government had become by 1997. On the other hand, isn’t that how most oppositions return to power?

Finally, there are the perennially hopeful Liberal Democrats. They clearly made progress in the 2005 elections, but the large gains they were hoping for did not materialize. Furthermore, because Britain’s parliamentary system does not reward parties with seats based on their overall percentage of the popular vote, minority parties such as the Liberal Democrats have a far smaller share of the seats in the House of Commons than their vote totals might suggest. (The Lib-Dems have 62 seats in the House of Commons, just 9 percent of the available seats, despite winning 22 percent of the national vote.) They remain a party of protest, hoping to garner the support of voters who are sick and tired of the big parties. The 2005 election showed that they just could not compete well against the Conservatives, even though the Conservatives were not well regarded on the broad national scale against Labour. Even angry and frustrated Conservative voters did not switch to the Lib-Dems. This must be very discouraging for the Liberal Democrats, who need to find another way to move forward and make the big breakthrough they talk constantly about.

The coming years should be an interesting time in British politics as all three parties struggle to find a way to put their 2005 disappointments behind them.