This essay is based on the forthcoming book Institutional Genes: Origins of China’s Institutions and Totalitarianism by Chenggang Xu.

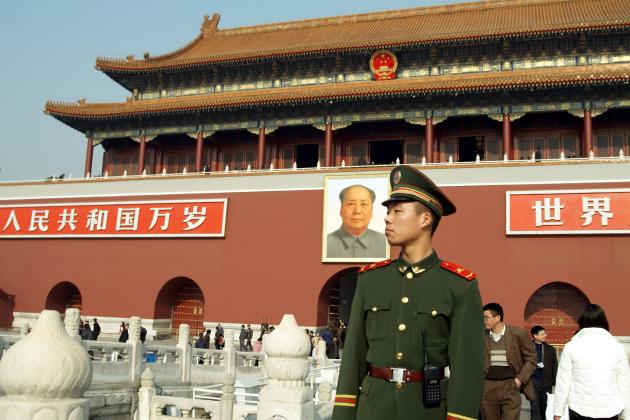

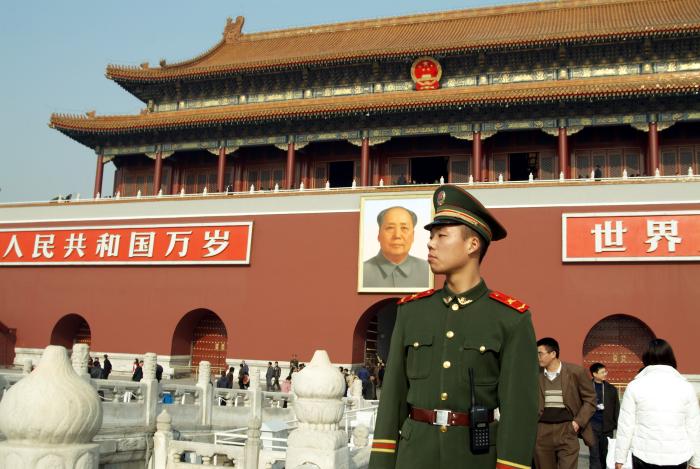

China’s fundamental institution is Communist totalitarianism. This is explicitly stated in China’s constitution, which declares that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leads everything, implying that it controls everything. In practice, the CCP monopolizes political powers in all branches of the government and in every corner of society, with its authority enforced through what it calls the “people’s democratic dictatorship.” Furthermore, the party-state is the sole owner of all land in China and controls nearly all major financial institutions.

My book, Institutional Genes: Origins of China’s Institutions and Totalitarianism, introduces the concept of institutional genes—fundamental institutional elements that self-replicate and shape institutional evolution—to analyze China’s institutional development. These genes encompass power structures, property rights, and the social consensus surrounding them.

Communist totalitarian ideology emerged in Western Europe and was first institutionalized in Russia. The institutional genes of the Bolsheviks—the first communist totalitarian party—included the tsarist imperial system, Russian Orthodoxy, and secretive political institutions, all inherited from the Russian Empire. These institutional genes merged with those of the Chinese imperial system through the influence of the Comintern—the Soviet agency that facilitated the spread of Communism—enabling totalitarianism to take root in China.

China’s Communist totalitarian regime was implanted by the Soviet Union in 1949. With Soviet assistance, the CCP seized power through civil war and then consolidated control by confiscating all land and capital through violent political campaigns. With absolute control over political power and economic assets, and under Soviet guidance, the CCP transformed China into a Soviet-style state—though it was significantly poorer at that time.

However, with deeply rooted institutional genes inherited from its imperial system, China soon diverged from the Soviet economic model through the Great Leap Forward (1958–61) and the Cultural Revolution (1966–76), both launched by Mao Zedong. These campaigns reshaped China’s administrative structure and reinforced totalitarian rule. Instead of maintaining a strict top-down central planning system like the Soviet Union, China evolved into a region-centered structure.

I refer to this uniquely Chinese totalitarian regime as regionally administered totalitarianism (RADT). The transition from Soviet-style totalitarianism to RADT came at a devastating cost: Tens of millions perished in the Great Famine caused by the Great Leap Forward, and millions more were purged during the Cultural Revolution.

Under RADT, the CCP has further centralized control surrounding strategic matters such as party lines, key personnel decisions, and ideology, while delegating most tactical matters—such as administrative management tasks—to regional (provincial and local) party-state agencies. This distinguishes RADT from the rigid Soviet model, in which central authorities maintained tight control over the detailed management of all state-owned enterprises.

The flexibility and adaptability of RADT enabled the CCP’s reforms, creating conditions for the private sector to grow, which differentiated China from its counterparts in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe (SU-EE). Since privatization is inherently contradictory to totalitarianism, it was strictly prohibited in SU-EE regimes, ultimately leading to the collapse of totalitarian rule there.

In China, however, the private sector emerged and expanded unintentionally from the perspective of the CCP’s central authorities. It was driven by highly incentivized local party-state bureaucrats, who engaged in fierce regional yardstick competition based on economic growth rates to advance their careers.

Since the 1990s, the private sector has become the primary engine of China’s economic growth, effectively saving the CCP from the fate of SU-EE Communist regimes. As a result, the CCP officially legalized private property rights in the constitution in 2004.

Importantly, alongside the rapid growth of the private sector, new types of institutional genes—favoring constitutionalism and democracy—emerged and expanded rapidly. These include civil society, awareness of human rights (including private property rights), and limited pluralism. This multifaceted relaxation gradually and unintentionally transformed China from a totalitarian system into an authoritarian one—more precisely, a form of regionally decentralized authoritarianism (RDA).

However, the CCP has been fully aware that losing control could undermine the foundation of its totalitarian rule, a scenario they believe led to the collapse of the SU-EE Communist regimes. In 1979, just before launching economic reforms, Deng Xiaoping introduced the Four Cardinal Principles to safeguard party control. Under his leadership, the CCP’s total control, socialism, proletarian dictatorship, and Marxist-Leninist-Maoist ideology became the four untouchable red lines of reform. These principles largely represent the old totalitarian institutional genes.

Since then, a tug-of-war has emerged between the new pro-democracy institutional genes and the old totalitarian ones. While these competing forces shaped the two-decade reform era, the CCP under Xi Jinping has reasserted rigid totalitarian control starting in 2013, reversing much of the liberalization that took root during the reform period.

To conclude, institutional genes evolve slowly, and their evolution is influenced by contingent factors.

Learn more about the book here.

Chenggang Xu is a senior research scholar at the Stanford Center on China’s Economy and Institutions and a visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution.

This essay is part of the Long-Run Prosperity Research Brief Series. Research briefs highlight research that enhances our understanding of the factors that drive long-run economic growth and examine its policy implications.