- Military

- Innovation

- Revitalizing History

- Understanding the Effects of Technology on Economics and Governance

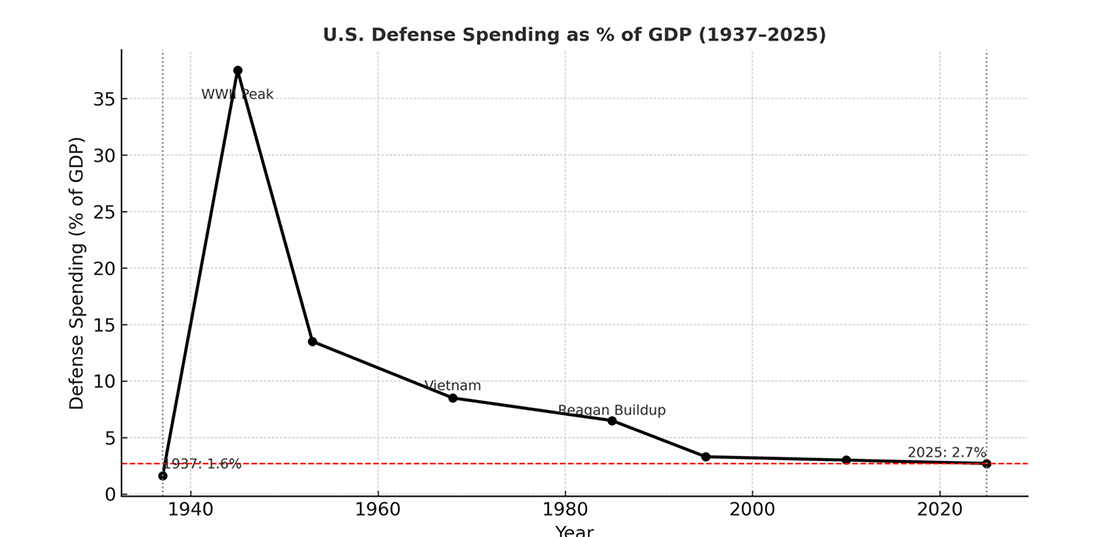

Needless wars needlessly lost have undercut support for the military. Currently funded at 2.7% of GDP, the Defense budget is the lowest since 1937, when the U.S. was caught in the Depression and totally unprepared for the coming war. In the five-year Defense plan, the Trump administration and the Congress do not increase that percentage. Quite the opposite: Our rising debt will continue to squeeze out Defense spending. A decade from now, procurement will be lower than it is today.

To avoid losing the next war, the Pentagon must radically change course. Two actions are imperative: fire the contractors and use that money to procure AI-driven unmanned systems.

1. Fire the support contractors. About 650,000 civilian contractors provide services to our military, at a cost of $270 billion, a quarter of the entire Defense budget. These are not the workers building ships and aircraft. Instead, service contractors perform everyday tasks (e.g., maintain computers, deliver supplies, patch communications, train the troops, etc.).

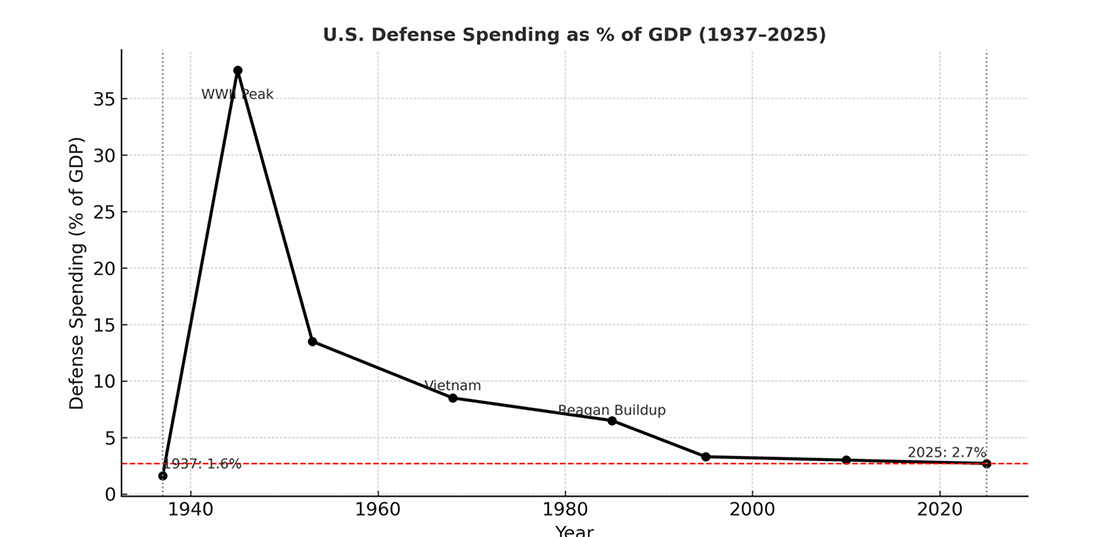

Since 1980, America’s combat arms forces have shrunk by 37% to about 400,000, while the contractor workforce supporting them has increased by 70%. In Iraq and Afghanistan, these service contractors saw unprecedented growth and did not abate after the wars ended.

A contractor costs twice as much as an O-6 or GS-15 doing the same work. The reason is that the contractor works for a mega corporation that has layers of well-paid executives, all requiring overhead and profit. Of the of $270 billion in mundane contractor support, at least $40 billion must be shifted to procure AI unmanned weapons.

2. Buy a Million Drones. AI-enabled unmanned systems have changed the face of twenty-first-century war. Russian ships have ceased sailing in most of the Black Sea. Drones have struck Russian airbases thousands of miles apart, and account for 70-80% of the frontline casualties. Ukraine has made drones central to its war effort, devoting roughly 30% of its defense budget to their procurement and use.

AI unmanned systems (drones and vessels) account for about 3% of the Defense budget. The U.S. Army and Marine Corps have exactly zero—not one—drones deployed in their 9,000 combat arms squads. In the commercial world, drones are a commodity, costing $500; U.S. military drones cost $50,000 per unit. Artillery rounds on average cost $1,500 per shell. Drones at the squad level should cost less than $500. They are munitions to be fired like mortar shells, nothing more and nothing less. Our exorbitant costs have placed us at a steep disadvantage.

The emphasis must be upon driving down costs of AI drones and delivery platforms. This requires adaptive competition among many small firms and government-private sector partnerships, while ensuring real-time feedback from the warfighters. The senior civilians in the Pentagon are emphasizing procurement decentralization. Defense Secretary Hegseth has authorized the operating forces, such as brigade commanders, to acquire cheap unmanned systems without having to seek permission from higher headquarters.

Going directly to the commercial market reduces overall costs because dozens of start-ups will offer their wares at competitive prices. Several hundred brands of shoes are sold annually in the United States. We don’t demand that everyone wear the same black shoe. Similarly, there can be dozens of suppliers of unmanned systems. Using this diversified approach, Ukraine is producing 4.5 million drones in 2025.

Congress is an impediment. To protect their local interests, the 535 members of Congress insert thousands of strict instructions into the procurement regulations, “We have 1,500 line items on things we need to buy,” a frustrated Secretary of the Army Daniel Driscoll said a few months ago. “We are in a holy war (against Congress) over 1% of our budget, to have the flexibility to buy different makes.”

Our services are also reluctant to change. In 1938, the best minds in France, England, Russia, and Germany went in different directions in procurement. France chose to defend by engineering, Britain began building fighter aircraft, Russia mass-produced inferior weapons, and Germany manufactured mechanized divisions.

Today, our four services are like those four countries—each going in a different direction. All four zealously protect their underfunded legacy systems—tanks, warships, aircraft, amphibious ships, etc. There is not one warfighting strategy against one enemy that provides a common pathway. The Air Force (31% of Defense budget) is investing in long-range, stand-off missiles launched from aircraft to strike deep inside China, targeting ports, air bases, command centers and missile installations. The Army (20% of budget) is foundering, with an undefined role in Pacific warfare. The Marines (4% of budget) have vacillating ideas but are tiny in any case. The Navy (26% of budget) is focused upon a sea battle against China, employing a surface fleet. In fiscal year 2025, the Navy allocated $20 billion for surface warships, versus $1 billion for unmanned vessels and drones. White House and Congressional support are strong for large, expensive warships, and for the jobs they create. This reflects an emotional reverence, if not nostalgia, for WWII, when large, manned vessels provided the firepower and logistical heft to propel our forces forward in both Europe and the Pacific.

But China’s satellites have turned the western Pacific into a transparent battlespace. Any carrier or amphibious ship near Taiwan will be surveilled and targeted by thousands of precision weapons. There is a brutal arithmetic to modern naval defense. The missiles to protect a carrier battle group cost millions of dollars each, while the drones that attack them cost tens of thousands. Our Navy must spend a million dollars to kill a $50,000 attacker—a losing exchange even before accounting for magazine limits and crew risk.

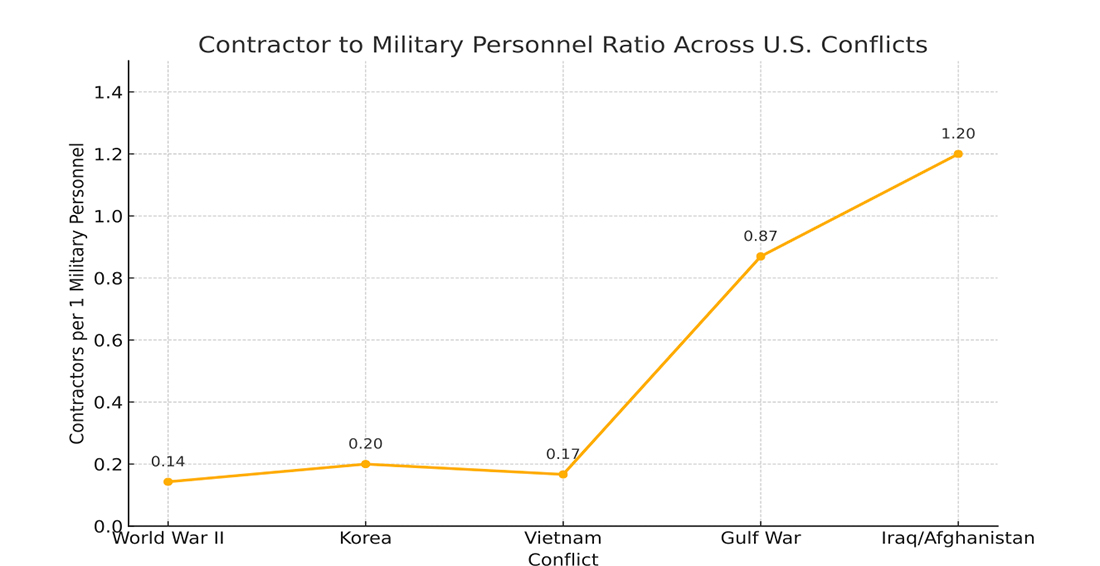

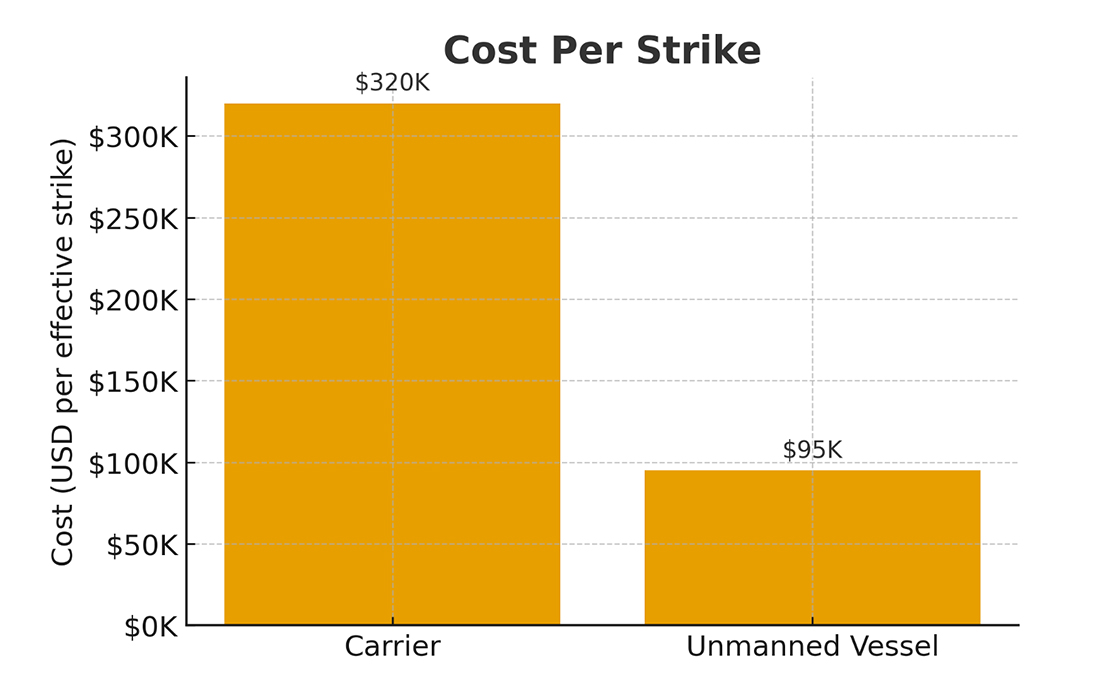

AI-equipped unmanned ships (200–300 feet long) can carry dozens of missiles or hundreds of small drones, and cost in the low hundreds of millions to build, versus $13–$15 billion for a single Ford-class carrier. The end purpose of the aircraft and its missiles on the carrier versus unmanned vessels packed with drones and missiles is the same: to destroy targets. Taking into account both costs and attrition rates per strike on target, unmanned vessels with AI-guided drones and missiles deliver strikes at a cost three times less than carriers and their escorts.

My sources (perhaps ironically!) for the analysis and the chart are Grok, Gemini, Claude, and Chat GPT. The data those AI models produced was voluminous. The chart and even the measure of effectiveness may be off the mark. But the issue—cheap AI unmanned systems versus our legacy manned systems—must be debated. DoD cannot continue to treat AI systems as a nice-to-have add-on.

Warfare in the twenty-first century is changing. Absorbability is the force multiplier in a strategy that depends upon attriting the enemy beyond his capacity to replenish.

If an attacking unit can launch thousands of cheap drones or missiles each day, it can deliver strikes for a fraction of what it costs the defender to intercept them. The defender’s magazines empty long before the attacker’s do. Unmanned, low-cost vessels hedge against catastrophic single-platform loss, provide magazine depth that sustains strikes on the enemy, and change the cost-exchange ratio so that attrition favors the U.S. Navy on the attack vs. China defending targets. A fleet of AI unmanned surface, subsurface, and aerial systems—cheap, numerous, and expendable—can absorb attrition, confuse Chinese targeting networks, and sustain operations when manned platforms must withdraw to distant, safer waters.

At Agincourt in 1415, the wealthy French knights brought tradition based on prior victories; the lowly English longbowmen brought cheap, mass firepower. English archers remained plentiful, long after France had run out of knights. In 2033, carrier battle groups are the knights—majestic, expensive, impossible to replace—while surface and aerial drones are the archers—disposable, numerous, and replaceable as a commodity. The historical comparison is obvious: The side that can absorb losses at 1/20th the cost wins the battle.

In summary, Congress will not increase the Defense budget. The Pentagon must transform itself by slashing its bloated contractor corps and cutting back legacy systems in order to put at least 25% a year of procurement into unmanned AI systems. To their credit, the senior civilian officials and the Pentagon DOGE team are fighting hard to achieve that transformation. The barrier is the fusion between Congress, the White House, major contractors, and the services—a coalition protecting legacy systems that are inferior on a cost per kill basis to cheap AI unmanned systems. Three percent funds for AI unmanned and 97% for WWII-era legacy weapons is a denial of twenty-first-century technology and commonsense.