- Security & Defense

- Determining America's Role in the World

“Our Words Matter.”

So begins a recent article in The Dive, a quarterly newsletter produced by the Intelligence Community Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility (IC DEIA) Office within the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI). The Dive is an internal publication, marked as unclassified but not for public release. Earlier this month, however, the ODNI, which oversees the operations of the nation’s 18 intelligence agencies, released a redacted version of the newsletter’s winter issue as part of a Freedom of Information Act records request. The theme of this issue was “the importance of words,” and the lead article was devoted to the “dilemma of problematic terminology” in counterterrorism.

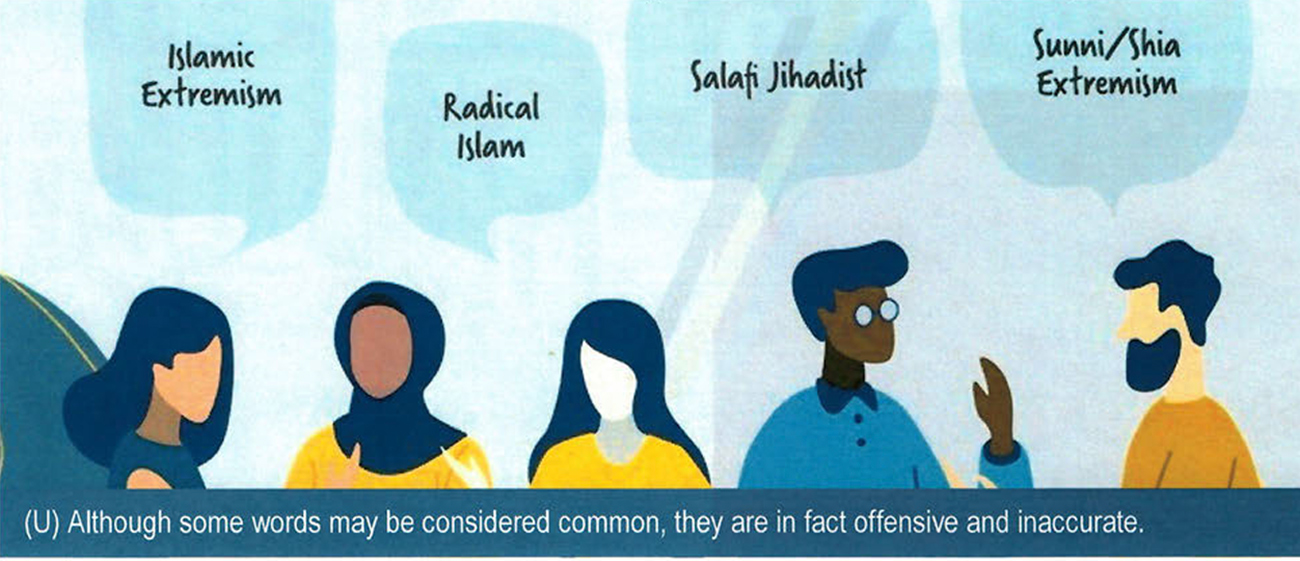

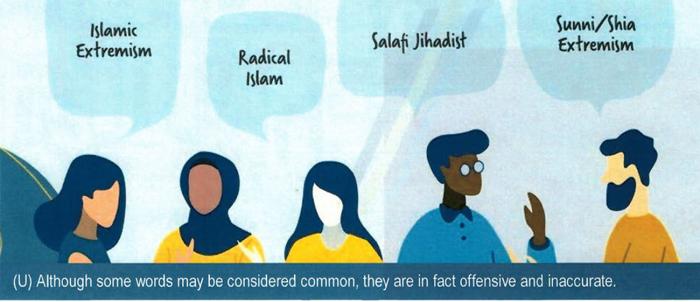

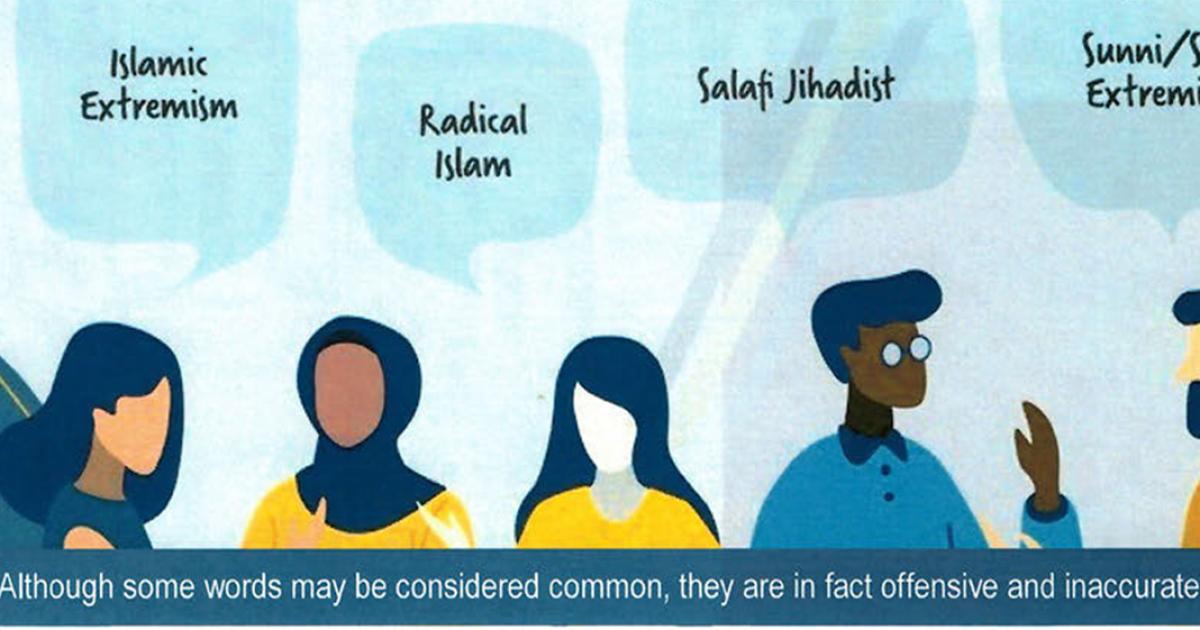

The article, titled “Words Matter: Changing Terminology Related to Counterterrorism,” highlights the IC DEIA’s efforts to influence the sorts of terms used by intelligence professionals in the context of counterterrorism. The goal, in short, is to “disentangl[e] Islam from words and phrases used to discuss terrorism and extremist violence.” Words such as “Salafi-Jihadist,” “Jihadist,” “Islamic-Extremist,” “Sunni/Shia-Extremism,” and “Radical Islamists” are held to be “offensive” and “problematic” on the grounds that they “incorrectly suggest that Islamic beliefs somehow condone the actions and rhetoric espoused by these foreign terrorist organizations.” Above the article is a graphic depicting a group of analysts using the words “Islamic extremism,” “radical Islam,” “Salafi Jihadist,” and “Sunni-Shia Extremism,” with a caption stating that “[a]lthough some words may be considered common, they are in fact offensive and inaccurate.”

If these terms are all offensive and accurate, then what does the IC DEIA propose instead?

“We recommend identifying individuals and groups based on the foreign terrorist organization they are a part of and the region where they operate …. Overall, it is encouraged to identify them for who they are—international terrorism extremists, or violent extremists—and explicitly state that they manipulate and distort Islam to wrongly justify violence. In cases where none of these substitute phrases are amenable, we recommend a word that many Islamic scholars, public leaders, and academics use to accurately identify extremists: Khawarij … We ask that employees spread awareness about the concern of the terminology we are seeing and utilize the substitute terms recommended to ensure we are inclusive, accurate, and sensitive.”

Several objections arise to this well-intended bit of terminological advice. Intelligence analysts covering terrorism are in the business of understanding the behavior, motives, and intentions of the terrorist groups they study. It is not their duty to “disentangle” them from Islam or to denounce them as inherently un-Islamic. To begin from the premise that groups such as al-Qaida and the Islamic State have nothing to do with Islam or are manifestly distorting and manipulating every aspect of the faith is to take a position with analytical import. It may be “sensitive” and “inclusive” in some sense, but it is not necessarily “accurate.”

How, and in what ways, these groups relate to and draw on the Islamic tradition is important for the intelligence community to understand and consider. It tells us about their motivations and intentions and the possible bases of their support. As it happens, al-Qaida and the Islamic State belong to a distinct movement within the larger Sunni Islamist frame known in Arabic as “Jihadi Salafism” (al-salafiyya al-jihadiyya) or “the jihadi current” (al-tayyar al-jihadi). These are not terms imposed upon them by the national security establishment but ones that they themselves use in their own discourse and internal debates. In assessing their status and future, it is important to understand that the jihadis form an ideological movement going back at least to the 1970s with a distinct doctrinal apparatus drawing on the Salafi tradition in Sunni Islam, a tradition informed above all by the theological writings of Ibn Taymiyya (d. 1328) and his more militant heirs in the Wahhabi movement that took form in 18th-century Arabia. They are also motivated by a unique approach to jihad that sees armed struggle against the perceived impious regimes of the Islamic world as an individual duty binding on all able-bodied Muslims.

None of this should be taken to imply that Jihadi Salafism is representative of mainstream Islamic beliefs and practices. It is not. But to deny intelligence analysts access to terms like “Jihadi Salafi” and “jihadi” is only to deny them access to these groups’ own frame of reference. One cannot possibly hope to understand what motivates them, what they aim to achieve, or the limits of their appeal if one is denied entry into their own worldview. Words like “international terrorism extremists” and “violent extremists” tell us little about the actors they are intended to describe. They are fine as neutral descriptors but are inadequate to the task of nuanced analysis.

Even less helpful is the suggestion of Khawarij—an Arabic plural more commonly anglicized as Kharijites. The Kharijites were a seventh-century Muslim sect remembered in the Islamic heresiographical tradition as extremist schismatics who eagerly fought and excommunicated fellow Muslims. They were also deeply pious. The Kharijite label has long been used as a derogatory term for versions of Islam seen as extreme by the mainstream. The Wahhabis, for instance, were branded by their enemies as Kharijites. It did not stop them from conquering most of the Arabian Peninsula by the early nineteenth century.

To call modern-day Islamic extremists Khawarij is thus to enter into a world of intra-Islamic polemic. This may have some utility in the realm of public diplomacy (though that is certainly debatable) but in the realm of analysis it is mostly counterproductive. The term is misleading in giving the impression that the jihadis are followers of a seventh-century schismatic sect when in fact they identify with the theological and legal heritage of Sunni Islam. The jihadis do not see themselves as Kharijites and in fact present themselves, pursuant to the Salafi tradition, as occupying a theological middle ground between the unbounded zealotry of the Kharijites and the laxity of the Murji’ites (another early Muslim sect). Referring to them as Kharijites misses the way that they understand and portray themselves.

Another problem with the Kharijite label is that the term is used by the jihadis in their internal debates. Within the jihadi current there is considerable ideological disagreement, particularly as regards takfir, or the practice of declaring someone to be an unbeliever. Followers of the Islamic State are more inclined to pronounce takfir on perceived heretics, including the Shia, than are followers of al-Qaida. This disagreement goes some way in explaining the ideological cleavage between the two groups. They are not the same, and in fact al-Qaida has sought to brand the Islamic State as Khawarij, the very term the IC DEIA recommends the intelligence community use for both groups. Why it is helpful to get drawn into internal Islamic polemic is hardly self-evident.

Since 9/11, American politicians have struggled with the question of how to identify and classify the enemy in what soon became known as the “war on terror.” In general, our politicians have shied away from emphasizing the Islamic dimension of the threat, in some cases arguing that the jihadis do not represent Islam at all. As President George Bush said after 9/11, “The face of terror is not the true faith of Islam,” and as President Barack Obama said about the Islamic State in 2015, “ISIL does not speak for Islam. They are thugs and killers.” Such comments might make sense in the context of public diplomacy. The question is whether they belong in the context of intelligence, where dispassionate analysis, unencumbered and unconstrained by political or other bias, is supposed to rule the day. Clearly, the IC DEIA, with its language initiative, believes they do. And according to The Dive, “our initiative is gaining traction across the USG and has been positively received by so many, including executive leaders.”

If true, this is a concerning development to say the least. If there is any place in the U.S. government where one ought to be free to assess terrorist groups on their own terms and without restrictions imposed by biased parties, it is surely the intelligence community. The IC DEIA, by seeking to constrain the terminology that analysts are allowed to use, only makes their job more difficult if not impossible.

Restricting the use of terms such as “Jihadi Salafi” and “jihadi” does not make the problem go away, it only obscures it. By narrowing the range of language, to borrow from Orwell, you inevitably “narrow the range of thought.” It is in that sense, above all, that our words matter.