- Security & Defense

- US Defense

In recent years, the transatlantic relationship has witnessed some of the greatest debates and differences recorded in U.S.-European relations, most recently concerning the war in Iraq. Not surprisingly, this turbulence has also generated a growing debate over the nature and causes of such differences. A number of different views have been advanced. One explanation suggests that such differences are largely attributable to the policies of the Bush administration. Another argues that the advent of the Bush administration is not a major factor and that the two sides have grown increasingly incompatible as a result of the growing asymmetry in power across the Atlantic. Yet another argues that current differences are essentially rooted in widely differing threat perceptions in the United States and Europe after 9-11.

It is perhaps inevitable that proponents of each of these views will look for — and sometimes find — public opinion research results that tend to confirm their own differing hypotheses. At the same time, the core issue of where and why American and European publics differ on questions of war and peace has not yet been adequately addressed. Here, drawing on the 2002 and 2003 Transatlantic Trends survey conducted by the German Marshall Fund of the United States, we attempt to dig a bit deeper into the nature and structure of the transatlantic divide.

Several conclusions can be drawn from what we have learned from the Transatlantic Trends results. For one, fears about American or European isolationism are misplaced. The American public is more willing to play an active role in world affairs than at any time in recent memory. Similarly, there is clear support in principle across Europe for the European Union to take on global responsibility, though that support is tempered by a limited willingness to spend resources.

Americans and Europeans basically still like each other, although such warmth has recently waned in the wake of the Iraq war. This drop in fellow-feeling, however, begins from an historically very high level. While the Iraq war has led to a backlash, it is noteworthy that the backlash has remained modest. To some degree it appears focused mainly on the Bush administration as opposed to the United States more generally.1 Anti-American and anti-European sentiments may exist, but they are not dominant views. Americans and Europeans continue to have clear, shared views of their friends and enemies, and each side still clearly sees the other as a friend. All of this testifies to the continued durability of traditional transatlantic ties.

Americans and Europeans continue to regard each other as potential partners. While European support for America’s global role under President Bush has fallen, such slippage also takes place at a high level. Americans are strongly supportive of the European Union becoming a more equal partner, and both sides of the Atlantic continue to see their relations as cooperative and not competitive.

Nor do the problems across the Atlantic appear rooted in radically different threat perceptions following September 11, 2001. On the contrary, Transatlantic Trends suggests that when Americans and Europeans look out at the world, they by and large assess the threats they face in similar terms. Americans and Europeans do not live on different planets when it comes to viewing the threats around them. Both sides of the Atlantic clearly do have different impulses when it comes to how to respond to such threats, however, concerning the efficacy and legitimacy of military versus economic power and the role of the United Nations. Yet even here it is not entirely clear to what degree transatlantic differences on the use of force reflect fundamental moral principles, more transient attitudes contingent on specific events, or an overall European skepticism about policies publicly associated with the Bush administration.

So what is going on? If Americans and Europeans both want to be engaged in the world, still basically like one another, would like to work together as partners, and also see the threats facing both sides of the Atlantic in similar ways, how and why did we end up with such a dramatic divergence in public opinion over the war in Iraq? Why did President Bush end up with a clear majority supporting war in Iraq — with little need, as far as domestic politics is concerned, to seek authorization from the United Nations Security Council? Why was Tony Blair so keen on getting such a resolution, and why was obtaining it so crucial for convincing British public opinion that the war was just? And why was public opinion in some continental European countries so strongly opposed to war and seemingly so different from the United States? Why did some leaders in the alliance seem to have considerable leeway when it came to public opinion in their countries, yet others faced very real and formidable constraints?

A foreign policy typology

So begin answering such questions, one needs to identify the more fundamental beliefs that drive and shape public opinion. The question we want to address, therefore, relates not only to differences across the Atlantic, but also to differences within both the United States and European countries on these issues. To accomplish this, we have developed a typology of foreign policy attitudes centered on different views of different kinds of power (e.g., economic vs. military power, or “hard” and “soft” power) as well as the efficacy and legitimacy of their use. These metrics were chosen because they form the core of the alleged transatlantic divide. Combining different attitudes towards both economic and military power and the acceptability of military force, we distinguish four distinct groups.

First, Hawks: Members of this school believe that war is sometimes necessary to obtain justice and that military power is more important than economic power. They also tend to be wary of international institutions, especially the United Nations. They are not interested in strengthening the U.N. and are willing to bypass it when using force.

Second, Pragmatists: Members of this school also believe that war is sometimes necessary to obtain justice but that economic power is becoming more important than military power. They tend to assign an important role to international institutions, including the United Nations, and favor strengthening them. They prefer to act with multilateral legitimacy but are also prepared to act without it to defend their national interests if need be.

Third, Doves: Members of this school disagree that war is sometimes necessary and believe that economic power is becoming more important than military power. Like Pragmatists, they want to strengthen institutions like the United Nations. Unlike Pragmatists, however, they are very reluctant to use force absent international legitimacy.

Fourth, Isolationists: Members of this group believe neither that war is sometimes necessary nor that economic power is becoming more important in world affairs.

To operationalize this typology, we examine two key questions. Respondents were asked to agree or disagree with the following statements: 1) “Under some conditions war is necessary to obtain justice,” and 2) “Economic power is becoming more important in the world than military power.” Combining and cross-tabulating the answers and excluding the missing cases one arrives at these figures for the relative sizes of the four distinct groups.

How sturdy is this typology? Does it really capture the underlying differences between and within the United States and Europe? There are two different tests one can apply to check the resilience of this breakdown. The first one is what is called face validity. The key question here is whether the typology makes intuitive sense and gives us the confidence to argue that different attitudes on just war or the role of economic power reflect deeper convictions that carry over to other issues. Given the prominent place of considerations about the use of power in thinking about international affairs, we find that it does.

The second and more important test is what is referred to as construct validity. Does our index help to predict other foreign policy attitudes? And do these predictions follow the direction our theory would suggest? The first question is relevant, but the second is actually more important. To test the validity of the typology, we cross-tabulated it across a wider set of foreign policy attitudes and found that it did indeed function well as a predictor of certain key attitudes. We provide some examples.

Attitudes on the war with Iraq: Hawks are likely to support the Iraq war and to judge it worth the costs more than any other group, followed closely by Pragmatists and only at a distance by Isolationists and Doves. Of the Hawks, 55 percent (along with 48 percent of Pragmatists) “think the war in Iraq was worth the loss of life and other costs” while only 12 percent of Doves and 15 percent of Isolationists think so.

The United Nations: Hawks are also less likely to want to strengthen the United Nations and more likely to agree that one is justified in bypassing the United Nations when vital interests are involved. Pragmatists and Doves both want to strengthen the U.N., but Pragmatists are still willing to bypass it if necessary to defend vital interests.

Military expenditures: Hawks are likely to say we are spending “too little” or “the right amount” on defense whereas Doves are likely to think that we are spending “too much.” Among Hawks, 30 percent think we are spending “too little” and 47 percent think we are spending “the right amount” while, among Doves, 40 percent think we are spending “too much.”

Economic aid: Doves are likely to say that we are spending “too little” and Hawks are likely to say we are spending “too much” on economic aid. Almost half of the Hawks think we are spending “too much” on economic aid while only 36 percent of the Doves think so.

Attitudes toward the use of force: Hawks are more likely to support the use of military force than Doves in all the scenarios tested in our survey (e.g., scenarios involving the acquisition by North Korea and Iran of nuclear weapons) irrespective of the kind of mandate that does or does not exist. They are also more likely to prefer military action to economic sanctions across different scenarios. In a hypothetical international crisis, 58 percent of Hawks are willing to impose economic sanctions while 71 percent are willing to do so among the Pragmatists and 79 percent among the Doves.

Attitudes toward internationalism: Both in Europe and in America, there is an undercurrent of isolationism among the Doves. This relationship is apparent in the United States, where Doves are often less internationalist than Hawks or Pragmatists. In Europe, this relationship holds in some countries, such as Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, and the United Kingdom. In France and Italy, however, those who believe in soft power also exhibit greater tendencies towards internationalism. On many of these issues, Pragmatists tend to adopt a middle position between Hawks and Doves.

What does this tell us?

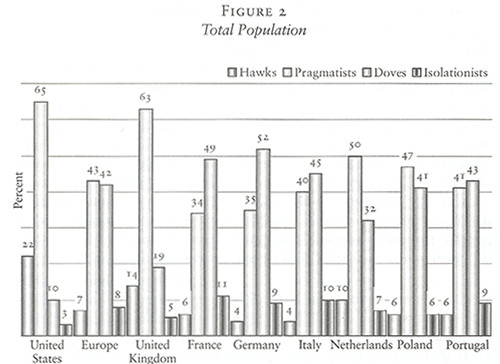

This typology reveals some interesting differences in terms of the structure of American and European public opinion. In the United States, Hawks constitute more than one in five Americans, or 22 percent of the public (and 33 percent of Republicans). They are three times as numerous as in Europe (see Figure 2). Pragmatists, in turn, constitute nearly a two-thirds majority at 65 percent. In contrast, Doves are a small minority at 10 percent and Isolationists compose only 3 percent of the populace.

When it comes to the structure of public opinion in Europe, in most of the countries we surveyed, the two dominant groups are Pragmatists and Doves. Moreover, these two groups basically balance each other — at 43 percent and 42 percent, respectively. Both the Hawkish and the Isolationist groups are small minorities — just 7 percent and 8 percent — when one aggregates the European countries surveyed.

At the same time, these overall European numbers mask some noteworthy differences among the countries. In the case of the United Kingdom, for example, the structure of public opinion is similar to that of the United States. At the other end of the spectrum, Germany differs considerably. The latter has the smallest percentage of Hawks and Pragmatists as well as the largest number of Doves. Whereas in the United Kingdom, Hawks and Pragmatists combine for a total of 77 percent, in Germany they amount to about half of that figure: a mere 39 percent. Apart from the United Kingdom, the other European countries in which Pragmatists are more strongly represented are the Netherlands and Poland. In both of these countries, the combination of Hawks and Pragmatists constitutes a slim majority. At the other end of the European spectrum are Germany and France, where Doves are the dominant school.

What does this suggest? In the United States, an American president — irrespective of his political persuasion — has considerable leeway in building public support when it comes to the use of force. It is possible to imagine differing coalitions forming depending on the issue and the party in power at any given time. One would be a coalition between Hawks and Pragmatists; a second might be a narrower base of Pragmatists alone; and a third could be an alliance between Pragmatists and Doves.

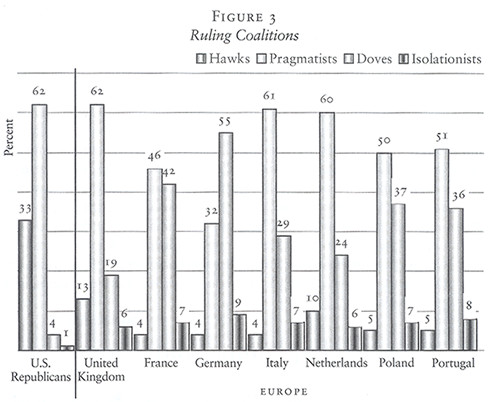

In Europe, the dynamics are likely to be quite different (see Figure 3). In many (if not all) of the countries surveyed, the key to building stable and broad public support is a coalition between the two dominant groups: Pragmatists and Doves. The former are concentrated on the center-right and the latter on the center-left. Given the dominant size of these two schools in Europe and the way in which they are reflected in the party landscape, the nature of the public debate and the constraints on the ability of a government to use force are unavoidably different than in the United States. The Hawks are too small to be a major or even relevant force in Europe (with the United Kingdom being a possible exception). Nowhere on the continent are they numerous enough to be a major pillar of public support. There may be cases — the Netherlands or Poland, for example — where a union of Hawks and Pragmatists could form a slim majority, but such a majority is likely to be narrow and not a viable basis for long-term policy.

What can one deduce from this reality? Obviously, there are important differences in the structure of public opinion across the Atlantic — as well as within Europe — when it comes to attitudes on the use of force. Perhaps the most noteworthy differences are the dominant size of the Pragmatists and the greater size of the Hawks in the United States. The potential pool of public support in the United States is much larger than in most European countries. The greater size of these groups clearly affects the options available to an American president when it comes to building public support for going to war.

Does this gap mean that the U.S. and Europe are somehow mismatched or incapable of cooperative action on such questions? Clearly, if one were to sit an American Hawk across the table from a German Dove, they would not have much in common. They might even conclude that one comes from Mars and the other from Venus. Yet the same might be true in the United States if one paired a Bush Republican with a Howard Dean Democrat. If one were to pair an American Pragmatist with a European Pragmatist, on the other hand, they would in all likelihood have few problems devising a common agenda.

Explaining Iraq

The foreign policy typology can help us understand what happened on both sides of the Atlantic in the debate over the war in Iraq. The categories capture existing predispositions within the respective groups to differing arguments about the potential use of force. The ability of a government to mobilize or capture that potential on a real-world issue is, of course, a different matter. Figure 4 shows the results of a question posed in this year’s Transatlantic Trends survey regarding whether the war in Iraq was worth the loss of life and other costs associated with the operation. The figure presents the aggregate numbers for the countries surveyed.

Figure 5, in turn, shows the breakdown of this support for (and opposition to) the Iraq war based on the typology we have developed. It allows us to see how much public support for the war existed within each of these groups and how they contributed to the total support or opposition. It also helps explain the very different political debates that took place in the United States, the United Kingdom, and continental Europe on the question of war in Iraq and the freedom (or constraints) that public opinion provided to (or imposed on) ruling governments. The figure illustrates the comfortable position of some leaders and the awkward situation of others. Let us look at some of the individual countries.

In the case of the United States, President Bush’s point of departure was the much larger pool of potential supporters based on the size of the Pragmatists and Hawks. The 60 percent majority of Americans who believe that the war in Iraq was worth the costs comes overwhelmingly from these two groups. Nearly three in four Hawks — and two in three Pragmatists — believe that the war was worth the costs. Such support was overwhelming among Republicans but also reached into the ranks of the Democratic Party. The support, moreover, was not dependent on obtaining further international legitimacy via the United Nations or a clearer demonstration that force was unavoidable. Due to the absence of such steps, American Doves overwhelmingly opposed the war.

Although the structure of British public opinion is similar to the structure of public opinion in the United States, Prime Minister Tony Blair faced a different political lineup, especially within his own Labour Party. Majority support for going to war in Iraq was potentially within reach for Blair, but the dynamics of how to get there were quite different. In contrast to Bush, Blair could not rely on a coalition of Hawks and Pragmatists within his own party. Indeed, the Labour Party straddles the Pragmatist-Dove fault line typical of European countries. In order to bring his own party behind him, Blair needed a rationale that appealed to both Pragmatists and Doves. Blair’s lower level of support on Iraq reflects the lower level of support he enjoyed from the right — only slightly more than half of British Hawks (55 percent) and Pragmatists (53 percent) backed his position — combined with skepticism among British Doves that the war was worth the costs. Only 28 percent of Doves in Britain believe it was. The prime minister’s effort to secure a second Security Council resolution made good political sense as an attempt, albeit an ultimately unsuccessful one, to gain the kind of international legitimacy that could have given him greater support within this constituency.

In Germany, the debate over Iraq took place in a public opinion landscape significantly different from that of the United States or Britain. First, the potential pool of support for military action in Iraq was much smaller. Whereas Hawks and Pragmatists amount to over 80 percent of the American and British publics, together they account for fewer than half of Germans (39 percent). Among the supporters of Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder — and within the ruling Social Democratic-Green coalition — they are even fewer. But what is striking in Germany is how many Hawks and Pragmatists also opposed the war. At the end of the day, the fact that over 85 percent of Germans do not believe the Iraq war was worth the costs reflects not only the dominance of Doves in Germany, but the Bush administration’s inability to gain anything but the most tepid support among German Hawks and Pragmatists as well.

Support for the war in the Netherlands (41 percent) was more than double that in Germany (15 percent) and nearly three times higher than in France (13 percent). That higher level of support reflects those differences in the structure of Dutch public opinion discussed in the previous section — in particular the greater number of Pragmatists. Some 61 percent of this group supported the war. What is interesting in the case of Italy is that whereas overall support for the Iraq war is low (28 percent), Italian President Silvio Berlusconi enjoyed the support of more than half (52 percent) of Italian Pragmatists — who are arguably an important part of his party’s constituency even though they are fewer in number than the Doves for the country as a whole. In the cases of France, Poland, and Portugal, there was very little public space for supporting the Bush administration’s approach on Iraq among the groups supporting the ruling coalitions.

These results show that if one goes beyond an aggregate analysis of the overall public to a more detailed analysis of the voters supporting the ruling coalition, it can help explain why different leaders in Europe were able — or compelled — to pursue very different policies.

Looking into the future

The transatlantic trends 2003 survey also included a series of questions addressing public attitudes towards the use of force to prevent either North Korea or Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons. Respondents were asked whether they would support the use of force across a spectrum that included unilateral U.S. action, a U.S.-led coalition of the willing, a nato operation, or, finally, an action sanctioned by the United Nations Security Council. As noted in the survey, these were experimental questions. Moreover, with respect to the levels of support for the use of force, the specific scenarios described may also have conditioned the answers.2 One therefore needs to be cautious about drawing broad conclusions from these data. Bearing this caveat in mind, applying the typology developed above allows us to examine how support for the use of force varies among the four groups in our typology in both the United States and Europe.

Figure 6 shows the aggregate responses to these questions for the United States and the European countries surveyed. It shows that there is a clear gap between the American and European publics surveyed of over 30 percent.

In Figures 7-9 we break down that support in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Europe according to our typology. Several interesting conclusions stand out. First, the results confirm that the United States remains in a league of its own. Nearly 80 percent of the Hawks and of the Pragmatists support the use of force; this support hardly fluctuates as one moves across the spectrum from unilateral U.S. action to action with a United Nations mandate. These two groups, it should be recalled, dominate the American landscape. In the case of American Doves, however, support is very low for a unilateral action or one involving a coalition of the willing but climbs considerably when a nato or U.N. action is involved. The latter drives support for military action among Doves from around 30 percentage points to over 60. Clearly, the United States holds a reservoir of potential public support for the use of force to prevent Iran and North Korea from acquiring nuclear weapons.

In the case of the United Kingdom, we again find a structure that has much in common with America, but with some important differences. There is majority support for the use of force across the spectrum among Hawks and Pragmatists, though at a slightly lower level than in the United States. Like their American brethren, support for military action among British Doves is also heavily contingent on the level of perceived international legitimacy. That support climbs nearly 30 percent as one moves from a hypothetical unilateral U.S. action to one sanctioned by the Security Council. While the overall level of support among British Doves remains lower than in the United States, it is higher than in any other European country.

For Europe as a whole, one again sees that the lower level of support is rooted in the same key factors discussed above. Support for military action is very weak among Doves — who are a key, if not dominant, faction in most countries. In contrast to the United States and the United Kingdom, support does not increase significantly as one moves across the legitimacy spectrum — at least not for the scenarios involving Iran and North Korea. Although there is potential support among European Pragmatists and Hawks, there are too few of them to bring the overall European levels of potential support close to that of the United States.

The degree to which these scenarios are indicative of overall views on the use of force is not clear. One wonders whether European support might be higher, for example, when it comes to a scenario in the Balkans along the lines of Bosnia or Kosovo. Nevertheless, these numbers do suggest that building public support for the use of force in a scenario involving Iran or North Korea will be an uphill struggle with the structure of European public opinion as it is. While one can imagine support coming from the Hawk school, moving beyond that core and generating additional support from the Doves would require considerable work given their proclivity against the use of force and their strong belief in the need for international consensus.

Irrespective of the particular scenario, Europeans more strongly require international support to create legitimacy for military action. Our analysis shows that it makes a significant difference whether a potential military action involves a unilateral U.S. move or one supported by nato or the United Nations. While our typology is a strong predictor of differences across the Atlantic as well as between eu countries, the issue of whether the action is unilateral or multilateral is also a critical variable.

Support for the use of force increases if the operation is conducted under the auspices of a multilateral institution such as nato. In Europe support increases under the various modalities from 36 percent for the U.S. acting alone to 48 percent for an action under a U.N. mandate. For the U.S. these percentages are 70 percent and 79 percent, respectively. In short, while the U.S. and European patterns are similar, for the scenarios we surveyed there is a clear gap of some 30 percent across the Atlantic when it comes to willingness to use force.

This does not mean that our typology is any less valid. While the unilateral/multilateral nature of the action clearly makes a difference in terms of support for the use of force, our typology is still a very important predictor of attitudes (as shown in Figures 7-9). Across the entire spectrum of possible military operations, both Pragmatists and Hawks are systematically more willing to support the use of force than Doves and Isolationists. Figures 7 and 8 also reveal that in the U.S., the multilateral nature of the action might have a greater role to play as compared to Europe. In Europe, there is no interaction effect between the nature of the action (unilateral/multilateral) and our typology (see graph), while such an interaction effect is present among the Doves in America. However, until this group is needed, the Bush administration can ignore all appeals to multilateralism if it sees fit.

In this connection, the British case is again quite interesting, as it seems to combine elements of both the American and European political landscapes (see Figure 9). One can easily see the dilemma that Prime Minister Blair could face if he were to contemplate joining the U.S. in military action. First, in the United Kingdom the degree of multilateral support is crucial for obtaining support among the Pragmatists. In contrast to President Bush, this is the key constituency to which Blair must appeal and on which he must rely for public support given the small number of Hawks in the United Kingdom (and even fewer in the Labour Party). To obtain anything more than a slim national majority and achieve broader public support, Blair must also be able to reach into the Doves whose potential support is extremely sensitive to the nature of the action (unilateral/multilateral), as shown in Figure 9. This group, therefore, can be mobilized towards opposing the war on the issue of the lack of multilateral support.

Building support

Looking behind aggregate survey results reveals additional insights into structural differences in public attitudes on both sides of the Atlantic. Here, we have focused on public attitudes towards the potential use of force due to the key role that this issue appears to play in the recent transatlantic friction. On this and other key issues it is important to understand the building blocks that underlie public attitudes in the United States and Europe.

The typology introduced here suggests that the transatlantic divide is less a “gap” between America and Europe than the effect of the differing structures of attitudes on the use of force and the relative size and weight of differing groupings in different countries of the alliance. Clearly, these differing structures are critical in shaping domestic debates and in framing the strategies that political leaders can pursue in questions of war and peace.

Just how important such decisions are is clearly shown by the example of Iraq. President Bush chose a specific strategy and rationale to make the case for war. The strategy was politically viable in the United States, and especially within his own party, in terms of generating public support. However, Bush’s strategy and argument were unlikely to work in many European countries given the different structures of attitudes that exist there, especially on the continent. Whether an alternative strategy might also have worked in the United States, or would have been more effective in Europe, is one of those interesting questions that historians may ponder.

What is clear is that in building support for particular foreign policies, including the use of military force, all leaders must be sensitive both to their own and to their allies’ domestic constituencies if they hope to forge coalitions to act together. One of the key tensions for leaders to manage is between the divergent instincts and preferences of Hawks and Doves when it comes to issues of just war, the use of force, and international legitimacy. In the absence of such efforts, even modest differences in the structure of public attitudes can have far-reaching consequences in public debates. The natural coalitions that emerge on both sides of the Atlantic may continue to cluster at opposite ends of the political spectrum — and hence aggravate a relationship already under tension in spite of broad agreement on the nature and urgency of common threats.

In practical terms, an American president can indeed seek to form a working majority, built on a coalition between Hawks and Pragmatists, for using force absent a U.N. mandate, as was the case on Iraq. No European leader can attempt to pursue such a strategy and hope to gain majority public support, with the possible exception of the uk prime minister. This does not mean that European leaders cannot mobilize public support for going to war or using force. It does mean, however, that a different justification would be needed to win public support. In most European countries, such support would consist of a coalition between Pragmatists and Doves. This is the partnership Tony Blair sought to build in the United Kingdom during the Iraq conflict.

The particular approach American leaders take to build support for their policies in Europe matters a great deal. An American president who pursues a unilateral and hawkish foreign policy course may be able to bank on public support in the United States, but he is going to have a hard time gaining public support in Europe — irrespective of who is in power across the pond. If Washington is interested in restoring a viable transatlantic consensus when it comes to the use of force, it must recognize the need to develop grounds for such action that take into account the distinctive requirements of European public opinion — especially when they are so different from those in the United States.

1 This question was not addressed directly in the 2003 Transatlantic Trends survey, although, as we shall argue, the study does contain some clues in a more indirect fashion. Other recent polls provide at least partial answers. The Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Project, in a survey held at about the same time as the Transatlantic Trends survey (May 2003), found in this connection that people who demonstrated unfavorable attitudes towards the U.S. by and large did so because of how they felt about President Bush and not because of their views on America in general. This was true for 74 percent of those who had negative feelings in general in France and Germany, while figures for other European countries showed a similar effect (67 percent in Italy, 59 percent in Great Britain, and 50 percent in Spain). Likewise, in an April-May 2003 Gallup International survey, majorities in 38 out of 43 countries agreed that the Iraq war had had a negative effect on their opinion concerning the United States.

2 One should not forget, however, that the figures showing lower support for the use of force among Europeans were probably contaminated by the fact that the cases concerned, Iran and North Korea, are seen by large numbers of people as part of the “Bush agenda,” and thus elicit an immediate refusal to support military action in some quarters. The figures should not be taken as absolute indicators of a (lower) level of support for the use of force in general. This is an issue where the respondents are acutely sensitive to a question’s background and wording. For example, more complicated questions with more answer categories — or that mention alternative policy options — tend to reduce the support for the use of force among American respondents while increasing it among Europeans.