- History

- Military

Russian forces numbering around 130,000 troops armed with tanks, infantry fighting vehicles, artillery, and other weapons of mobile combined arms warfare have massed on the Ukrainian border. Another 35,000 rebels and 3,000 Russian advisors are positioned inside the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine. More Russian troops are deploying into Belarus to the north, enabling Russian forces to attack towards Kyiv on two fronts should Vladimir Putin decide to invade. What are Putin’s goals vis-à-vis Ukraine, and why is he willing to go to war to accomplish them?

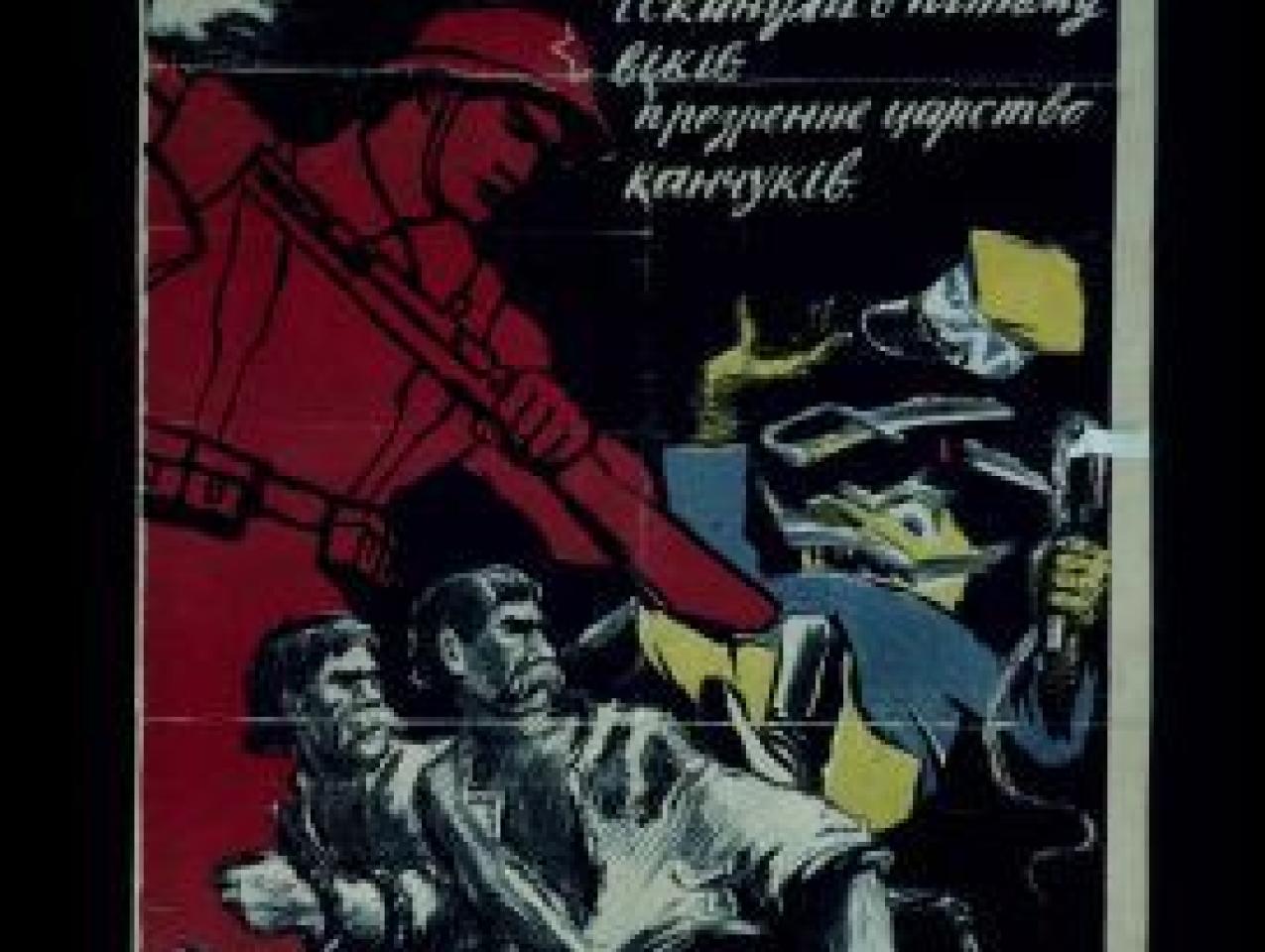

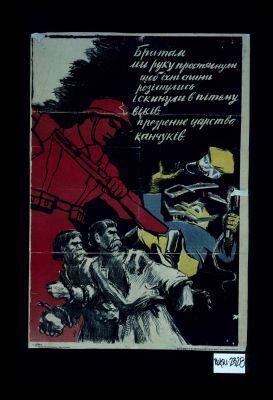

To understand Putin’s mindset, one must appreciate his historical view of Ukraine and its place in the “Russian World.” Both Russia and Ukraine trace their roots to the Kyivan Rus’ (from which come the names of Russia and Belarus), which ruled the area from the 10th century until its extinction by the Mongol invasion in the mid-13th century. Although subsequent political entities ruling over portions of Ukrainian lands include the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Republic of Genoa, the Crimean Khanate, the Cossack Hetmanate, and the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian Empires, in Putin’s view Ukraine has always been an inseparable partner of the Russian Empire. Never mind that the Great Famine in 1932-1933 precipitated by Soviet policies killed millions of Ukrainians, or that the Germans were able to raise a division of Ukrainian troops to help them fight the Red Army during World War II.

The other significant factor shaping Putin’s mindset is his belief that the dissolution of the Soviet Union “was the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century,” a “genuine tragedy” that left millions of ethnic Russians outside of Russian territory. Adding insult to injury, several rounds of NATO enlargement have left Western military forces on Russia’s doorstep. To forestall further expansion of the alliance, Putin invaded Georgia in 2008 and fomented a conflict in the Donbas region of Ukraine in 2014. Both countries have declared themselves NATO aspirants, which appears to be a red line for the Russian president. Thus, his major demand for backing down from the ongoing crisis of his own creation is a written pledge by NATO not to expand further into Eastern Europe. Such a pledge will allow Putin to achieve his goal of fashioning a pliable and friendly Ukraine which will be a junior partner to Moscow and supportive of its foreign policy.

NATO, of course, will not allow Putin to dictate its future. Even though Ukrainian accession to the alliance is unlikely given its ongoing conflict with Russia, member nations have rejected Putin’s demands regarding enlargement of the alliance. They have gone further and have ramped up their arming of Ukraine, sending hundreds of anti-tank and anti-aircraft weapons to Kyiv in preparation for a potential Russian invasion. NATO countries have also reinforced eastern members of the alliance with naval and air forces, and the Biden administration has plans to send upwards of eight-thousand troops to the region to demonstrate American commitment. President Joe Biden has taken intervention in a war between Russia and Ukraine off the table but has threatened severe economic and financial sanctions should Russian forces invade.

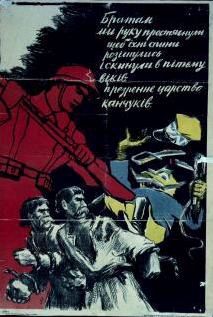

The vast majority of Ukrainians reject Putin’s reading of their history. The number of Ukrainians who remember being part of the Soviet Union is steadily shrinking, boding ill for Putin’s goal of bringing that country back into partnership with Russia. Time is not on his side, and Putin knows it. Ukrainians will fight to retain their sovereignty, as they have many times in the past. Russian forces may invade, and if they do, they will likely prevail. But military triumph will come at a price. If war comes, it will be the largest conflict in Europe since the end of World War II and it will open the door to the workings of uncertainty and chance, the twin handmaidens of disaster throughout history.