For decades, George and I talked practically every Sunday. On several occasions, we promised each other to participate at the other’s memorial service. Knowing George, he will in all likelihood have found some ingenious way to uphold his end of the bargain, perhaps drafting remarks welcoming me to his present location. I am in no hurry to find out, especially as I still need to qualify for where he is.

Some years ago, I said in an interview: “If I were in a position to choose a president, I would select George Shultz.”

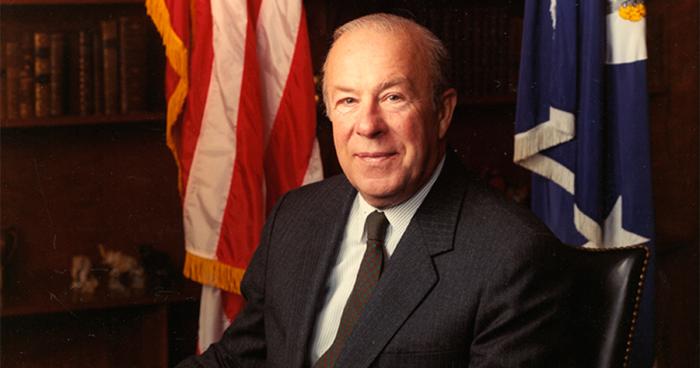

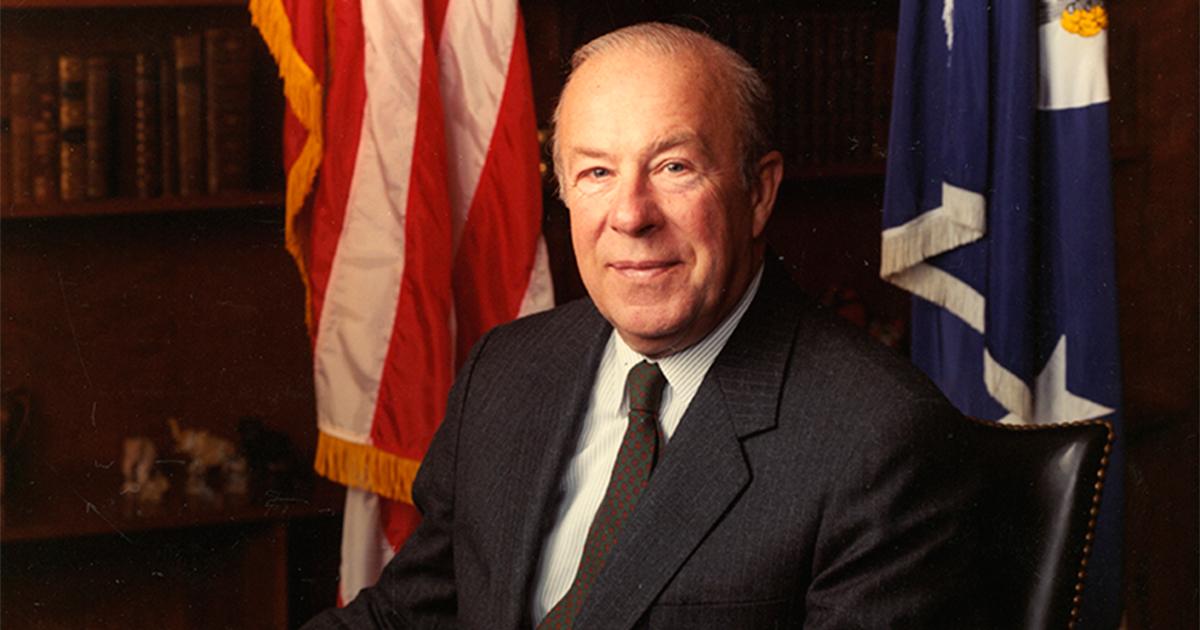

George’s defining quality was his wisdom, which was frequently sought by presidents and caused him to be rotated through a succession of Cabinet posts until he became one of the most consequential Secretaries of State. George’s wisdom was of two types: the Greek phronesis, or practical judgment, considered by Aristotle as indispensable for statesmen; and the Hebrew chokhmah, or divine wisdom, for which Solomon prayed. Aristotelian wisdom is concerned with squaring means and ends; Biblical wisdom stresses the importance of choosing worthy ends.

In the pursuit of phronesis, George identified the key problems of our time and explored solutions to them by involving committed individuals in discussion groups, often at the Hoover Institution. When you received George’s summons, it contained no option of refusal. The only open subject was the extent of your cooperation. And so, into a Biblical age, he devoted himself to the most vexing challenges of our times: arms control, climate change, public debt, demography, and how to keep a high-tech world focused on the moral imperative of its progress and overcome the inherent danger of self-destruction.

In the other part of his life, George practiced chokhmah. He was blessed, like Solomon, with a “wise and discerning heart.” On his 100th birthday, George wrote that he was devoted to “doing big, hard things together.” Like Tennyson’s Ulysses, he believed that “something ere the end / Some work of noble note, may yet be done.” In that spirit, George spearheaded several Track II groups in recent decades, convened with the purpose of preventing adversarial relations from becoming institutionalized and seeking goals that might unite humanity. The efforts were always discussed with high officials in all administrations both before and after the meetings.

George was aware that schemes for human improvement can go wrong. But for him, recognizing the tragic presented a spur to constructive actions. George had been a Marine and remained one all his life, and Marines do not wallow in problems; they solve them. Having written movingly of his efforts during the Nixon administration to desegregate public schools, George recognized that Americans were inheritors of the past, but he never accepted that they were prisoners of it. George believed deeply in America’s destiny and capacity for renewal, and he saw in it a duty to enhance humanity.

I cannot end this summary of a lifetime of friendship without also paying tribute to Charlotte, who sustained George with her love, her dignity, her sense of the intangibles, and her devotion.

Near the end of his presidency, Charles de Gaulle is reported to have confided: “For centuries, we and the Germans have traversed the world, usually competitively, looking for a hidden treasure, only to find that there is no hidden treasure, and only friendship is left to us.” George did not have to traverse the world to reach this conclusion; he started with it. And this is why this service of his friends and admirers is not one of sadness but of uplift. George remains with us in his love of country and in the sense of responsibility to construct a worthy legacy.