- Energy & Environment

- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

Dateline Kyoto. It became immediately apparent that your intrepid correspondent had ventured into enemy territory when he read the flier in his room: "We, Hotel Granvia, have a great concern for ecology and will enforce the following matters to help prevent the destructive climate changes. . . . We will only exchange those towels on the basin top. Please only use one soap during your stay. The map of Kyoto is a product of recycled paper."

For further confirmation, he had only to scan the material all conference participants received, which contained the following pledges: "It was concluded in Japan that the whole nation would take thorough energy-saving measures on both corporate and individual levels. Our plan includes setting the temperature of heater equipment at no higher than twenty degrees centigrade (sixty-eight degrees Fahrenheit)." (The Granvia had missed the word, and my hotel room was overheated. I had to ask the bellboy to turn it down.) "To realize these goals, it will be required that we accept a new lifestyle, including wearing warmer clothes."

Fair enough. But wait a minute! "The use of heating equipment in the conference rooms or the reception rooms will be as moderate as possible during the meeting. In this connection, we are planning to distribute shawls to you upon request in order for you to feel comfortable. Printed on each shawl is a logo 'Smart Life with Energy Saving,' showing the importance of an environmentally sound lifestyle. Distribution will be made to a hundred people each day on a first-come, first-serve basis."

Great. A thousand shawls. Ten thousand participants.

| Since government officials were busy schmoozing with one another, members of the press were forced to interview themselves. |

In keeping with the spirit of the occasion, the thermostat was indeed turned down from its normal seventy-three degrees to sixty-eight degrees, cutting the conference hall's heating bill by about 2 percent (that should save the planet!). The financially straitened Greenpeace, some forty-one rabble-rousers strong, erected a humongous solar-powered kitchen with an environmentally friendly refrigerator run by $20,000 worth of solar panels jutting fifteen feet into the air--something all homemakers hunger for. They even treated us to free solar-brewed coffee, at least when the sun was shining. The organization also exhibited a huge metal dinosaur made of scrap auto parts--at least it was recycling.

Clearly Al Gore was in safe hands. (A rumor circulated that the real reason Gore had come to Kyoto was that he had heard it has the largest number of Buddhist temples with the most generous congregations in all Asia.)

Why Am I Here?

As a representative of a nongovernmental organization (or NGO, in U.N. jargon), I was given a badge, a tote bag, the right to stand around in the corridors and watch the proceedings on video, and the right to attend almost anything any other NGO wanted to present. It turned out that some NGOs were more equal than others: Critics of a climate treaty were thrown out of one NGO meeting for not being of the faith.

By the close of the conference, all of us, believers and nonbelievers alike, were standing around waiting for word on what was being decided behind closed doors.

In the interim, since government officials were busy schmoozing with one another, members of the press were forced to interview themselves and then, in desperation, the NGOs. As a result, I was taped by CNN, National Public Radio, and French television. (I missed out on MTV, Nickelodeon, and the Comedy Channel.)

On the third day, we NGOs were given special permission to observe from the fourth-floor balcony the plenary session of the "Conference of Parties," or, as it was affectionately known by its friends, COP3. Each government made an "intervention" to justify the cost of its being in Kyoto. The delegates themselves were vying to congratulate the chairman on his election, haranguing the First World to give them more money, and protesting the requirement that they use market principles. It was a stultifying sight. By the end of the first hour, your correspondent had resorted to playing solitaire on the computer; others were catching up on their sleep.

What Happened

From the start, the ninety-seven-member U.S. delegation refused to answer any questions about the discrepancy between the satellite and balloon data and surface-measured temperatures. The most important item on its agenda was securing agreement on the international bureaucratic organization that would oversee the new regime.

The delegates believed that the White House had come up with a plan that would eliminate the threat of global warming, would be fair to all, and would not harm the world's economy. They also claimed other countries would soon see the wisdom of Washington and that the tooth fairy was. . . .

The U.S. representatives spent the mornings at secret sessions, where they put forward positions already decided by Washington. Later they broke into smaller groups to repeat their previous statements. In the late afternoon, they gave reports, first to the several hundred representatives of U.S. business, then to the greater number of U.S. representatives of environmental organizations, and finally to the press. In the end, the best the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration representative could come up with when pressed about the satellite data was that it did not measure ground-level temperatures.

| One group demonstrated against air travel. I assume they wanted us to return home by ship—preferably sailboat. |

During the conference, we were informed that the modality of evolution was stymied but would be taken up by a contact group; that, for unknown reasons, the European Union wouldn't budge on the bubble; and that the United States supported limited differentiation. The Quantified Emission Limitation and Reduction Objectives (QELROs) group debated the number of gases to be covered, and the United States insisted on joint implementation. Note: If you understood the previous two sentences, please go to the next conference in my place.

In all, more than ten thousand delegates, environmentalists, NGOs, and journalists (some thirty-five hundred strong) registered for this torture. Two major forests may have given their all to provide the gigantic amount of paper put out daily. Conditions were so crowded that it was hard to find working space. Attendees complained that, when they found a seat, they could not locate the table under the mound of paper, laptops, pamphlets, cameras, and empty plastic bottles.

Weather or Not

One of the newsletters published at the conference, Eco, a green publication, reported, "It was a lovely day, rather hot for December. It seemed that climate was on our side." Now if they could take their instinctive preference for global warming and translate it into policy, we could put all of this to rest. In fact, nature was not kind to global warming agitators. It snowed. The building was cold, and many chilly participants were wearing coats indoors.

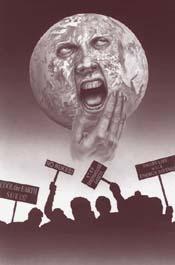

The Kyoto conference eventually degenerated into a cross between a revival meeting and guerrilla warfare. One night a group held a prayer meeting around the outdoor ice sculptures, pleading for their forgiveness as the ice began to melt.

The Korean Federation of Environment Movements put signs on bushes outside the entrance proclaiming "Cool the Earth, Save Us," "Reduce GHGs [greenhouse gases] 20%," "Please: Gas Masks!" (Don't these bushes know that 95 percent of all plants will grow bigger faster in a world of enriched CO2?), "Silent but Angry," "No Nukes, No Fossil Fuel for Us" (Do they want us to freeze?). On the last day, a Japanese environmental group organized a demonstration on behalf of forests. The trees, too, were against CO2! Another group demonstrated against air travel. I assume they wanted us to return home by ship, preferably sailboat.

Sound and Fury

The foregoing rendition has barely conveyed the overwhelmingly fundamentalist environmental flavor of the convention.

Indoctrinated children, copying AIDS activists, had made quilts proclaiming their abhorrence of global warming, and their colorful patchwork festooned the halls, which were swarming with young, earnest types. Vegetarian sandwiches sold out quickly at the snack bar, and one young man was overheard saying to an eager female environmentalist, "You must come up and see my wind farm." For the most part, the climate apocalyptists preached to the converted, spreading the gospel of an energy-free world. The only way to salvation was through abstinence or, in modern terminology, conservation.

Those of us who questioned the need for a treaty could be counted on one hand, while those who thought that no treaty would be strong enough to save the world were legion.

Amid all this sound and fury, the U.S. delegation signed an agreement that the Senate will not ratify, one that will not reduce greenhouse gas emissions significantly, one that, even if the computer models are right, will not have any measurable effect on the climate. It will, however, send jobs and money abroad.

Oh, well, as Al Gore would say, "It is a good start."

But on what?