- Middle East

- International Affairs

Earlier this summer, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu announced a plan to take control of Gaza City, historically the dominant and largest urban center in the Gaza Strip. The plan may have been the spark that has ignited a new set of negotiations that could bring the fighting to an end. It also can be viewed as the blueprint for an upcoming military campaign, which will be judged by its capacity to degrade Hamas further and limit civilian casualties. The ultimate meaning therefore depends on what enhances, and what impedes, progress toward a negotiated settlement.

Israel’s political-security cabinet endorsed the takeover plan August 7. The decision has not been without controversy, facing criticism from parts of the military leadership and members of the public, including families of the hostages, not to mention international figures. The announcement of the plan has led various European leaders, for example, to promise to recognize a Palestinian state, as discussed below. In the meantime, proposals for a truce, the release of Israelis held hostage by Hamas, a prisoner exchange, and increased humanitarian aid are all under consideration.

Hamas’s sudden return to discussions appears to be a response to the impending Israeli campaign. Whether Hamas’s intent is serious or only a stalling tactic will become evident soon. In the meantime, it is important to look back to how we got here.

Five goals

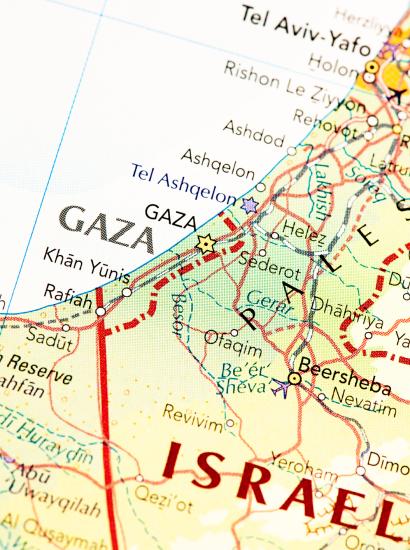

Gaza City, about 2.5 miles south of the Israeli border, is the city closest to the Erez Crossing with Israel, the border point where goods entered and left Gaza. That crossing was destroyed in the Hamas attack of October 7, 2023.

To understand the Gaza City plan, it is important to consider the course of the war thus far, as well as the political prospects. The fighting began in the wake of the October attacks, and by November 2, 2023, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) had initiated a siege of Gaza City, one of Hamas’s key strongholds. The siege continued for fourteen months until the cease-fire of January 19, 2025, when Israel withdrew from the Gaza City vicinity. The arrangement, promoted by the United States, Qatar, and Egypt, was intended to lead to further de-escalation, but the strategic pause in the fighting also carried the risk of Hamas’s return to control in the city.

Some hostages were released, a major concern of the Israeli public, but Hamas used the opportunity to stage propaganda events, parading the hostages before large jeering crowds. The spectacle was viewed as a breach of international norms. Hamas additionally used the cease-fire and the repositioning of Israel’s forces as a demonstration of its own capacity for survival. The cease-fire began to break down as early as February, with reciprocal accusations of breaches.

The new Israeli plan therefore should be seen as a response to the dissolution of the negotiated arrangement. It includes five goals: disarming Hamas; retrieving the hostages; a demilitarization of Gaza (that is, defanging not only Hamas but other militant groups as well); maintaining Israeli security capacity; and setting up a governance structure that does not include Hamas.

Each of these points deserves elaborate commentary. In brief, however, it is important to note that some of the European plans also mention disarming Hamas—although they typically do not condition their promised recognition of a Palestinian state on that point—but they do not stipulate how that disarming will take place. At this point, the only force engaged in a potential disarmament of Hamas is the IDF; the French or German army will certainly not take this on. The background concern is to avoid a situation that prevailed for years in Lebanon: in that country, according to UN Security Council Resolution 1701 of 2006, all militias were to be disarmed, but this goal was never applied to Hezbollah, with dire consequences for Lebanon and the region.

The plight of the hostages has been tearing at Israeli society since the October attacks. While Netanyahu has articulated the goal of retrieving hostages through fighting, an anti-war public, including the hostages’ families, urges for a negotiated release, whatever the terms. Those terms would likely include release of prisoners in Israeli jails who committed murder, including members of Hamas’s elite Nukhba brigade who led the October attack and were captured when the IDF belatedly engaged them.

The problem of postwar governance remains particularly difficult. Even if Hamas were out of the picture, a credible plan for a government structure has not yet been articulated. The Palestinian Authority, based in Ramallah in the West Bank, has little credibility, is rife with corruption, and is hardly a model of democracy. Israel has made it clear that it does not intend to govern Gaza (despite some extremist voices that argue for a return of Israeli settlement), but neither will it countenance a Hamas regime. Ultimately, an international authority, with extensive Arab participation and potentially authorized as a mandate by the United Nations, might be able to take this on.

Alternatives to war

Such are the context and the official rationale for the planned Gaza City campaign. Estimates indicate that it might take several months or up to half a year to carry out. Some fighting has already begun in the eastern suburbs of Sabra, Zeitoun, and Shuja’iyya. However, these should be understood as preparation for a larger ground assault. As in the whole Gaza war, Israel faces the challenge of combating an enemy that has embedded itself among civilians, using them as human shields, while also having constructed an extensive tunnel network underneath civilian structures.

The invasion has not yet gone into full gear. This is the point where war, or the threat of war, turns into politics by other means, to use Clausewitz’s famous formula. The prospect of the return to a full-fledged invasion has led to an acceleration of negotiation efforts.

On August 14—one week after the approval of the campaign plan—David Barnea, the director of the Mossad, met in Doha with Qatari Prime Minister Sheikh Mohammed bin Abdulrahman al-Thani concerning negotiations that could lead to a release of the hostages. Meanwhile, a Hamas delegation has traveled to Egypt to discuss a possible renewal of negotiations. Furthermore Steven Witkoff, the US special envoy for the Middle East, has been active; he was central to the initial negotiations, and he recently met with the Qatari prime minister.

Several factors point toward eventual success through negotiations and an end to the conflict. Not only has Hamas been significantly diminished, but so also has the whole “axis of resistance,” with its headquarters in Iran. Hamas has not been thoroughly erased but it is a shadow of its former self. What remains of its leadership or its backers in Qatar or elsewhere should tell it to quit, if only for the good of the Gazans. Alas, Hamas has never shown much concern for the civilians of Gaza.

Furthermore, the fighting, which Hamas cannot win, stands in the way of regional reconciliation in the form of an expansion of the Abraham Accords. Significant economic and development opportunities are at stake. Sooner or later, Hamas’s leaders may succumb to pressure from other Arab interests. And because the Abraham Accords are the signature element of President Trump’s strategy for the region, American pressure will continue to be brought to bear to reach a resolution.

Violent at heart

Other forces are pushing against peace. Above all, the character of Hamas as a specifically Islamist organization plays a role. It is not a paradigmatic secular “national liberation” movement; it is a spinoff of the Muslim Brotherhood, its flag bearing the credo of Islam. The nature of its brutality on October 7 demonstrates that it is cut from the same cloth as the Islamists in Syria who massacred Alawites, Christians, and Druze during the past months, as well as the Islamist terrorists who have attacked Christian communities across Africa, especially in Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Mozambique. The violence carried out by these cognate Islamist movements helps clarify Hamas’s character. What it did on October 7 is representative of Islamist warfare.

In addition, the rush by several Western governments to announce their eagerness to recognize a Palestinian state has been understood by Hamas as encouragement to keep fighting. The imminent recognition of Palestine is generally not linked to any conditions—not release of the hostages, establishment of credible governance structure, or even agreement on borders. UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s phrasing was particularly inept: he said the UK will recognize Palestine unless Israel accepts a cease-fire, which is a formula to motivate Hamas to raise its conditions or even refuse to agree. Not only have these European initiatives (along with similar announcements by Canada, Australia, and New Zealand) prolonged the ordeal of the hostages; they have positioned themselves at odds with the foreign policy of the Trump administration in a way that will not be conducive to strengthening the larger alliance.

The key to progress on the political front (in contrast to progress in the fighting) is an agreement among some Arab states to assume responsibility for Gaza governance. If, for example, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, and Jordan were to agree on a joint force to oversee Gaza without Hamas and with a program for rebuilding, a path would be clear. Yet, as of this writing, the extensive diplomacy necessary to put that program in place appears to be lacking.