- Law & Policy

In McCullen v. Coakley, the Supreme Court was confronted with a controversial First Amendment challenge to a Massachusetts statute that imposed a 35-foot buffer zone around abortion clinics. That law provided:

(b) No person shall knowingly enter or remain on a public way or sidewalk adjacent to a reproductive health care facility within a radius of 35 feet of any portion of an entrance, exit or driveway of a reproductive health care facility . . .

It then exempted from that statute (1) persons entering or leaving such facility (2) facility employees (3) public workers including law enforcement and ambulance personnel, and (4) the general public passing by on public streets.

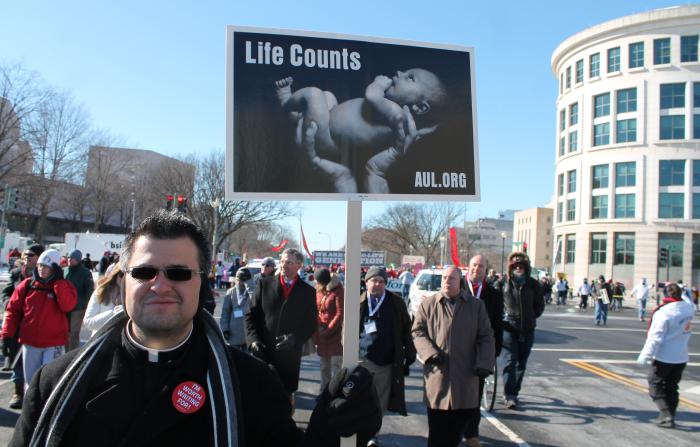

That statute was challenged by Eleanor McCullen, an antiabortion advocate, who claimed that it infringed on her right to offer “compassionate and caring alternatives” to women about to have an abortion. The Court unanimously struck down the law in two contrasting opinions. The five-member majority, headed by Chief Justice Roberts, included all four liberal justices. Its basic take was that this statute was content-neutral—remember it applies to all persons—in terms and was therefore subject to somewhat lower levels of scrutiny than content-based legislation. Nonetheless, the majority struck down the law because it was not ”narrowly tailored” insofar as it failed to consider less intrusive regulatory alternatives. Justice Antonin Scalia’s testy concurrence for the four conservative justices properly held that this is a content-based statute that did not meet a strict scrutiny standard.

In my view, the Court reaches the wrong outcome with respect to this prophylactic law. Justice Scalia is right that the Massachusetts law is content-based given that it only applies to abortion foes at abortion facilities, but he is wrong to think that the law should be struck down under a strict scrutiny standard. The statute should have been upheld, not struck down.

Freedom of Speech and the Common Law

Too much modern First Amendment law treats the guarantee “Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech, or the press” as if it imposes some special limits on Congress or the states above and beyond the protection of common law freedoms in ordinary disputes between private parties. This approach is destined to lead to serious error. The notion of “freedom” does not apply just to speech. It also extends to freedom of motion, contract, testation, and conscience, for starters. In practice, these freedoms often overlap. It becomes a major conceptual and administrative nightmare to let the level of constitutional protection vary with the nature of the underlying activity. It is, moreover, equally clear that none of these freedoms is absolute, but are subject to state regulation in the service of a wide range of proper ends. For our purposes, the key variable is that no conception of freedom, in speech or anywhere else, is broad enough to tolerate the use or threat of force against other persons. The same libertarian philosophy that accounts for the basic right also serves as the source of the correlative duties that all persons owe to one another.

One constant problem is how best to respond in advance to threats of force. Any approach faces two kinds of errors—overregulation and underregulation. Abortion foes should not be shut out from the opportunity of dissuading women from going through with abortions. But by the same token, any form of intimidation is off limits. From the nineteenth century onward, the line between force and persuasion has always been hard to police in labor picketing cases, both as a common law and constitutional matter, as the correct approach is often highly context dependent.

The issue is no simpler in abortion cases. With unruly crowds repeatedly massed at its doors, shouting at people who want to go through, the facility could obtain some form of injunction in routine fashion. The terms of that injunction would, of course, be contested, but any court would be well within its powers to adopt a fixed rule—stay 35 feet from the entrance way—to reduce the pressure of ad hoc disputes that always arise under some vaguer standard that compels demonstrators not to unduly harass or annoy potential patrons of the business acting in exercise of their constitutional right; for these purposes the soundness of Roe v. Wade is not in issue.

The sole difference in McCullen is that a Massachusetts statute, passed in response to numerous instances of threats and abuse, standardizes the outcome at 35 feet. In so doing, it gives clear notice to all concerned of their respective rights. If the distance chosen represents a good faith judgment about a sensible compromise, the legislation should be praised, not condemned.

The Constitutional Alternative

So how does the First Amendment change this analysis? In my view, not at all. Recall that the Amendment’s chief office is to prevent legislatures from eroding common law protections of freedom of speech, which did not happen in McCullen. End of case.

The common mistake of both the Roberts and Scalia opinions is to roll out the heavy constitutional apparatus. Its initial inquiry is whether this legislation should be regarded as content-neutral or content-specific. Hard to say, because the Massachusetts law applies to all persons, but only in the context of abortion clinics, where its sole conceivable application is against abortion protestors. But why enter into the fruitless classification debate at all?

Chief Justice Roberts treats this as a content-neutral law, like a “time, place, and manner” restriction, which is subject to lower levels of scrutiny, at least in name. But as an indignant New York Times editorial rightly points out, Roberts sugarcoats the record to make it seem that the plaintiff only wanted some cozy counseling sessions with women who were on the fence. But those counselors don’t cry out across picket lines to unwilling women who have hired escorts to help them run the gantlet. The risk of intimidation and force is serious, and the legislative record in Massachusetts shows that lesser means did not work well in many cases. It is not to the point to insist, as Chief Justice Roberts does, that streets and parks “have historically been closely associated with the transmission of ideas.” People can easily avoid stump speeches in a public park. But if there is only one entrance to an abortion clinic, it becomes a dangerous focal point that calls for extra protection. Why make Massachusetts extend this protection beyond the conflict zone just to undercut the constitutional challenge to the statute?

Nor is the Chief Justice on any better ground in suggesting that the state can deal with potential abuse case-by-case, like through the better enforcement of local traffic ordinances or police orders to unruly crowds to disperse. By that time, matters could easily get out of hand. Nonetheless he writes: “A painted line on the sidewalk is easy to enforce, but the prime objective of the First Amendment is not efficiency. In any case, we do not think that showing intentional obstruction is nearly so difficult in this context as respondents suggest.”

Perhaps efficiency is not “the prime objective of the First Amendment,” but he does not indicate what separate objective is better served by striking down this statute. Indeed, his bald pronouncement on enforcement difficulties is not supported by anything in the record and reflects an otherworldly ignorance of enforcement practices generally. Worse, his proposed alternative methods are costly and unreliable. They open up the police and the abortion clinic owners to legal challenges for overreaction in the particular case. They open the path for uneven enforcement. Perhaps only one Boston clinic has been subject to protestors, as the Chief Justice said, but if so, enforcing the statute will cause little or no dislocation at those clinics not mired in controversy. A common law tradition entrusts the choice of remedies to the sound discretion of trial judges. The same rule should apply to sensible statutory solutions. Massachusetts presented lots of evidence that a previous six-foot buffer zone offered no protection at all, yet the Chief Justice never explains why 35 feet is beyond the pale of reason.

Justice Scalia’s opinion is no better. Let’s assume that the Massachusetts law is content based. Why should a strict scrutiny standard apply here anyhow? Context matters. No one doubts that any statute allowing Republicans, but not Democrats, to give stump speeches in the park should be struck down. But in McCullen, such inequalities are not present. The activities of the abortion clinics’ speech are the lightning rod for protests. There is no system-wide imbalance in stopping abusive behavior that turns on the viewpoint of the critics. Rather, the greater the threat of force, the stronger the case for judicial intervention. We allow buffer zones around polling places, and around the Supreme Court, both far less tumultuous settings. Hence, they should be allowed here.

Simple Rules for a Complex World

It is tragi-comic that all nine Supreme Court justices have signed on to a set of ad hoc rules that can only make matters worse. One constant misconception in modern constitutional law is that ceaseless balancing somehow serves the interests of justice better than clear rules. As I have long argued, that is not true as a general matter. The proper approach starts with, for example, clear traffic rules that can be modified in the few cases where the violation of the rules by one party forces the other to improvise a response under pressure. The advantage of this two-stage approach is that it largely relies on clear rules that are cheap to administer, and easily known to all parties. The nasty refinements affect only a small subset of cases. The virtue of this two-step approach matters as much for speech as for driving. The Constitution does not require courts to abandon sensible rules for the creation and enforcement of legal rights and duties. The wrong outcome in McCullen shows the practical damage of an intellectualized approach that puts misplaced sophistication over common sense.