- Budget & Spending

- Economics

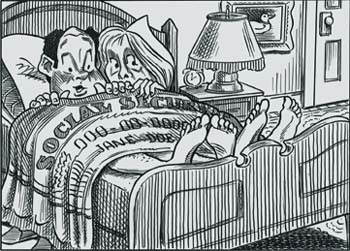

Illustration by Taylor Jones for the Hoover Digest Illustration by Taylor Jones for the Hoover Digest |

One of the most basic principles of economics is that people are better off if you allow them choice rather than force everyone to consume the same products. Choice allows people to pick products and investments that match their individual preferences and circumstances. The presence of widespread choice is one of the key differences between market-based economies and centrally planned ones. Over the past few decades we have seen many vivid demonstrations of the superiority of market-based economies. Social Security, however, is a program that offers almost no choice. Individuals cannot choose whether to participate, the pattern of benefit payouts, or the rate of return and riskiness of the program.

With the Social Security system edging toward insolvency, it is time to make some difficult choices about the future of the program. By instituting reforms that would offer people a degree of personal choice regarding financing their retirement, we can ensure that the system will remain solvent for future generations. But before discussing reforms, we should examine just how sick the current program is.

Social Security’s Problems, Real and Large

In 1967, the Nobel Prize–winning economist Paul Samuelson declared that Social Security was the most successful and popular of all government programs of the modern welfare state. He asserted that Social Security was a Ponzi scheme that actually worked in that each generation of Americans could expect to get far more in benefits from the system than they contributed to it. He certainly understood that Social Security was an intergenerational tax and transfer scheme; in fact, he "wrote the book" on that analysis. But, as long as the workforce grew by about 1.5 percent a year and real wages were rising by 2.5 percent a year, the system offered participants an apparent real and safe rate of return of roughly 4 percent a year.

Of course, the early participants in Social Security did much better than that. Obviously, any program that transfers resources from workers to the elderly will be a great deal for the first generation of elderly. Thus, those born in 1905 earned an average real rate of return of 10 percent. The rate of return was lower for those born later, but even those retiring at the normal retirement age in 1999 (and, hence, born in 1934) will enjoy a rate of return approximately equal to that offered by Treasury bonds. Social Security recipients who have retired in the past sixty years, then, have received more than $10 trillion in benefits in excess of their contributions. But the good times have come to an end. The growth in the workforce is slowing dramatically, reflecting the below-replacement birth rate that began in this country in 1970. The ranks of the retired are about to swell as the oldest of the baby boomers approach fifty-five and mortality improvements continue to outpace the assumptions of the Social Security actuaries. Making matters worse in terms of the finances of Social Security, people, particularly males, are retiring at earlier ages. Those retiring in the next couple of years will receive an average real return of roughly 2 percent, and later retirees will get much less, many less than 0 percent.

In the past sixty years Social Security recipients have received $10 trillion more in benefits than they contributed to the system.

Social Security is insolvent in the long run in the sense that the present value of future promised benefits exceeds the present value of future receipts for the program. The great unknown is how benefits and taxes will be adjusted to save the system from bankruptcy—but clearly either benefits will have to be cut or contributions increased. One other possibility is to use general tax revenues or the projected federal budget surplus to bail out the system. Some proposals claim to maintain current benefit levels without raising taxes and yet solve the solvency problem. Unless they are a complete hoax, however, they involve transferring trillions of dollars from general government revenues into the Social Security Trust Fund. This money should not be treated as if it were free; it could be used to finance personal income tax cuts, a payroll tax reduction, greater investments in higher education, new saving incentives, or anything else. The money belongs to the American public, just like any other source of funds. The calculation on whether we should devote this "surplus" money to shoring up Social Security should be similar to an analysis of raising Social Security payroll taxes. One is a decision not to lower taxes (or not spend additional money on education); the other is to raise taxes.

The trust fund now looks like it will become insolvent in 2032 (when the youngest baby boomer will be sixty-eight years old). In 1983 it was thought that the system would be able to finance the retirements of the baby boom generation without additional taxes or benefit cuts. Now the system is projected to require significant changes one year into the retirement of the youngest baby boomers. This deterioration in the outlook for the system is particularly surprising when you consider the fact that the U.S. economy has performed very well by most accounts since 1983.

All of this means that Social Security’s financial problems are real and large. The choices we face in order to bail the system out are not appealing. Either benefits have to be cut by roughly one-third, or taxes or contributions have to be raised by approximately the same percentage. There is no other way out of the current situation. Proposals that claim to maintain benefits without raising taxes can’t be taken seriously. Economists have been heard to say that there is no such thing as a free lunch. Unfortunately, it’s true in this case. Bailing out Social Security requires us to make some very tough choices.

The Options

To rethink the basic design of Social Security, we need to look at two fundamental choice dimensions. The first regards the structure of benefits and the allocation of investment risks. There are two types of pension programs—defined benefit plans and defined contribution plans. In a private defined benefit (DB) program, workers are promised particular benefits depending on the length of their career with the firm and their salary history while participating in the plan. A common DB plan offers workers some fraction of their final pay (say, 1.5 percent) times the number of years that they have worked under the plan. For instance, someone who worked for thirty years under such a plan would receive 45 percent of his or her final pay for the rest of his or her life (typically beginning at age sixty-five). From the workers’ point of view, the plan consists of a promised benefit formula and a lack of investment risk.

We face two choices—decreasing benefits by one-third or raising taxes by one-third.

The second type of private pension plan is termed defined contribution (DC). With a DC plan the employer promises to contribute a particular amount of money (or fraction of salary) into a tax-qualified pension account. The employer’s promise is limited to this funding amount. In contrast to participants in DB plans, DC plan participants bear the risk of the returns of the assets in the plan. Defined contribution plans come in a wide variety of types—IRA accounts, 401(k) accounts, 403(b) accounts, Keogh plans, profit-sharing plans, and so on. They have become increasingly popular, not only because of their relative administrative simplicity but also because of their flexibility in terms of asset allocation. People can choose to invest at the ratio of risk to return that they are comfortable with.

Social Security is a defined benefit plan. It has a particularly complicated formula for determining monthly benefits based on earnings history, age of retirement, and marital status. One thing separates Social Security from private plans, however; the promised benefits are largely (currently about 95 percent) unfunded. The program is what is called a pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) system. Each year most workers’ contributions are immediately paid to retirees rather than being invested in financial assets to provide for future benefits. Such a system is illegal for private employers but feasible for governments because they have the ability to fund promises with taxes on future workers. Currently, the unfunded liabilities of Social Security are roughly $11 trillion, which is the amount of money that today’s adults have been promised over and above what they themselves will contribute to the program over the remainder of their work lives.

Two-Tier Approaches to Social Security Reform

The current pay-as-you-go defined benefit Social Security system does not offer safe benefits for participants, as the public well understands. In survey after survey, working Americans express skepticism about Social Security’s ability to pay them benefits when they retire.

The riskiness of Social Security benefits is not only perceived but very real. The risks are that Social Security’s demographic and economic assumptions will not evolve as planned. PAYGO systems depend on a balance between the payroll taxes collected and the benefits paid out. But ours is not exactly a PAYGO system. Instead, we have both a defined or legislated structure of benefits and a defined or legislated structure of taxes. Only with great good fortune will the legislated tax rates generate enough revenue to finance the legislated benefits. If there are fewer future workers than had been assumed or if future real wages are lower than assumed or if mortality improves more than had been assumed by the Social Security actuaries, then the system’s finances will swing out of balance. Ultimately, the benefit structure or the tax structure must be adjusted to be consistent with the actual evolution of the demographic and economic structure of the country.

From a participant’s point of view, future benefits are risky because they depend on future fertility rates, productivity growth rates, labor force participation rates, retirement behavior, mortality improvement, and political uncertainties. Defined contribution plans also impose risks on participants, primarily the rates of return that investments will generate. The investment risks depend importantly on asset allocation. If a person invests in inflation-indexed U.S. government bonds, there is little investment risk. If the same person invests solely in an S&P 500 index fund, there is considerable investment risk, and, of course, there are riskier investment strategies than that. Note, however, that the types of risks inherent in a PAYGO Social Security system and those generated by a portfolio of private securities are quite different. In that circumstance, elementary portfolio theory tells us that the optimal thing to do is "some of each," meaning that for any given level of expected return, the total risks faced by participants can be lessened if they are allowed to combine both types of plans rather than being forced to specialize in one type of plan (and risk).

This analysis supports the desirability of so-called two-tier Social Security programs. The first tier would be a traditional PAYGO defined benefit plan. Presumably the benefit structure of this first tier would be lower than the current one in order to restore the solvency of the system. If the assumptions underlying this first tier are conservative, it could offer people a relatively safe floor level of benefits. The second tier would be a defined contribution type, presumably in the form of individual accounts that would offer people considerable choice in expected return and risk. Some people would choose to invest their tier-two money in conservative, safe assets, whereas others would assume more risks. The government may take a role in ensuring that people do not take extreme risks with even the second tier of a reformed Social Security system.

Today, the unfunded liabilities of Social Security are roughly $11 trillion—that’s trillion—which is the amount that today’s adults have been promised from the system over and above what they themselves will contribute to it.

This two-part structure has desirable properties in terms of risk allocation (everyone is protected from catastrophic market outcomes by the floor benefit of tier one), in terms of progressivity (the lifetime poor get a better deal than those more fortunate), and in terms of choice (the tier-two program offers individuals a wide range of choice of investments for their defined contribution accounts).

The Personal Security Accounts 2000 Plan

Syl Schieber and I have developed a two-tier proposal for Social Security reform that we call the Personal Security Accounts (PSA) 2000 plan. PSA 2000 is a two-tier Social Security proposal with defined benefit and defined contribution parts. The first tier continues to be funded with PAYGO financing. The first-tier benefit is $500 per month for workers with a full-length career, which would increase according to the growth in average real wages in the economy. Workers who have careers shorter than thirty-five years would get less than the full tier-one benefit.

The Social Security payroll tax (which is currently 12.4 percent of the first $72,600 of annual earnings) would remain unchanged. In addition, workers would be required to contribute 2.5 percent of their earnings (up to $72,600) into a personal security account that the government would match on a one-to-one basis, meaning that the accounts would actually receive deposits of 5.0 percent of the first $72,600 of pay.

The PSA money could be invested in a wide range of diversified assets offered by approved, private investment companies. There clearly would need to be government regulations regarding what assets could be placed in the PSA 2000 accounts. Still, individuals would be offered considerable choice: at a minimum, a total market equity index fund, a large-cap index fund, a small-cap index fund, a corporate bond fund, a money market fund, and an inflation-indexed government bond fund. In all probability, they would be offered a much wider range of choices than that, including a larger variety of actively managed mutual funds. That participants would be required to annuitize half their PSA balance on retirement is the string attached to the government’s one-to-one matching money.

Overall, we believe that the PSA 2000 plan would offer increased benefits for retirees, guarantee a safe floor benefit, and increase personal and national saving.

The transition to PSA 2000 would be gradual. Everyone over age fifty-five would continue to have full currently legislated benefits. Everyone under the age of thirty would participate only in the new PSA 2000 plan. Those between thirty and fifty-five when the new plan is adopted would get some old benefits and some new ones. The proposed system has been examined for actuarial soundness and would be balanced over the next seventy-five years. In fact, at the end of seventy-five years, the program would be running a large surplus and the basic payroll tax could be reduced by about 2.4 percentage points.

In terms of the policy options discussed earlier, low-wage earners would derive the majority of their benefits from the unfunded PAYGO defined benefit of tier one, whereas high-salary workers would get the bulk of their Social Security benefits from the funded, defined contribution tier-two PSA benefits. This strikes Schieber and me as a good system, retaining progressivity and properly allocating risk.

Conclusions

As a country, we face some important choices regarding the future of Social Security. We must either raise contributions to the program or curtail benefits or both. We can either retain the program’s unfunded defined benefit structure or move to a funded program of either a defined contribution or defined benefit type. I believe that the optimal solution is to move toward a hybrid plan that includes both an unfunded defined benefit part and a funded defined contribution component.

The problems of the Social Security system are compounding daily. Postponing decisions about how to fix it will only make the choices harder.

One advantage of adding the funded defined contribution part to the program is that it makes raising contributions more palatable. People are understandably reluctant to agree to yet another payroll tax increase to shore up the PAYGO system. We did that in 1977 and again in 1983, and it didn’t work for the long run; the current Social Security system has experienced chronic financial difficulties ever since it matured in the early 1970s. People almost certainly, however, would be willing to contribute more to their retirements via individual accounts; witness the enormous popularity of individually directed retirement accounts such as IRAs and 401(k) plans. The one-to-one matching program I have suggested for Social Security should also make the contribution increase substantially more appealing.

People would be more willing to increase contributions to an individual account because it is their private property. They would control the choice of investments and be able to choose a portfolio appropriate to their circumstances. The additional mandatory contribution would not be a tax per se. Instead it would be a required payment to a subsidized (i.e., matched) account for the participant’s own retirement. The universal participation in financial markets implied by the tier-two part of the PSA 2000 plan would improve financial literacy, increase national savings, and allow people a wide range of choices for providing for their own retirements.

One final thought about the social and personal choices we face regarding Social Security is that we should make them sooner rather than later. The system’s financial problems are compounding with daily interest. Postponing decisions about how to restore Social Security’s financial solvency will only make the choices harder. The long-run benefits of a new system designed to increase national saving, permit individual choice, and ensure a decent standard of living for elderly Americans will be enjoyed sooner if we make the important choices ASAP.