- International Affairs

- Key Countries / Regions

- Middle East

On Time magazine’s cover in 1947 was Arnold Toynbee, the then world’s most renowned scholar, author of the monumental ten-volume, A Study of History, praised for “Taking all the knowable human past as his province, he has found rhythms and patterns which any less panoramic view could scarcely have detected.”1

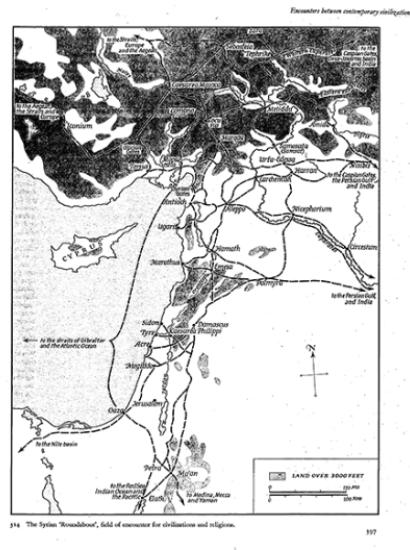

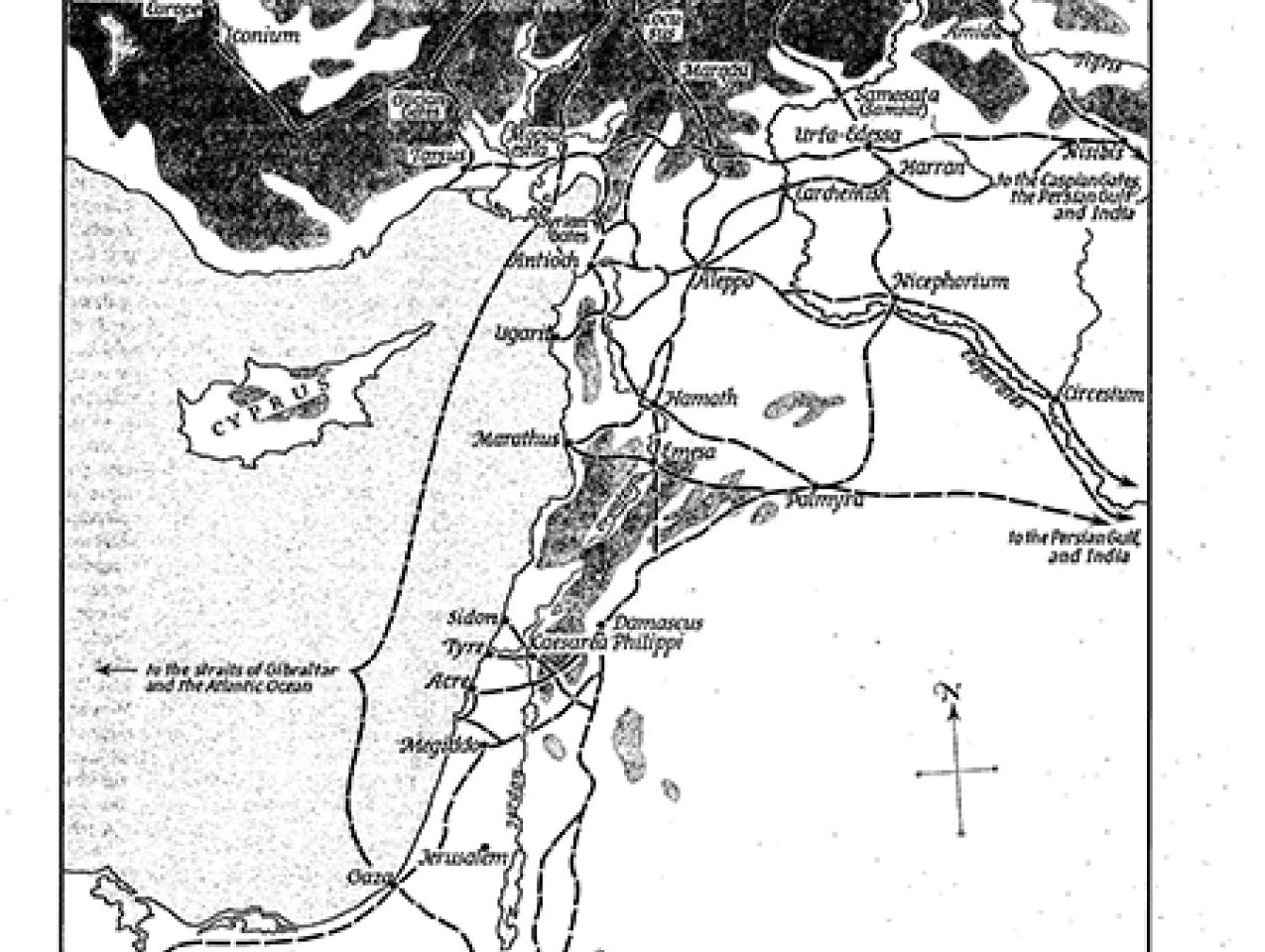

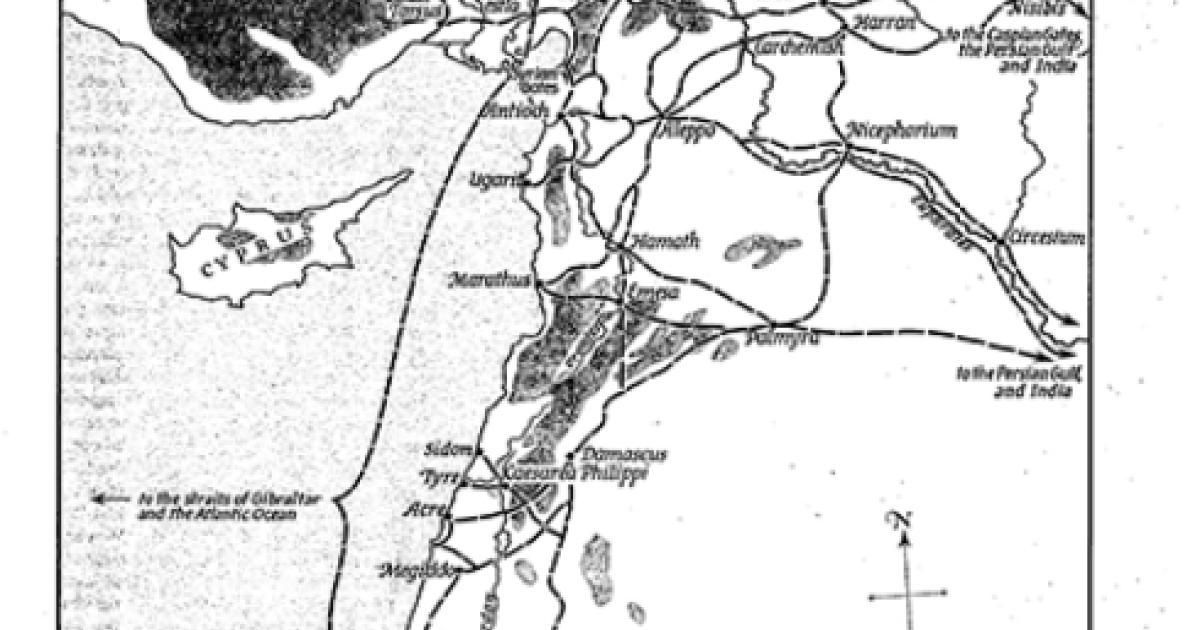

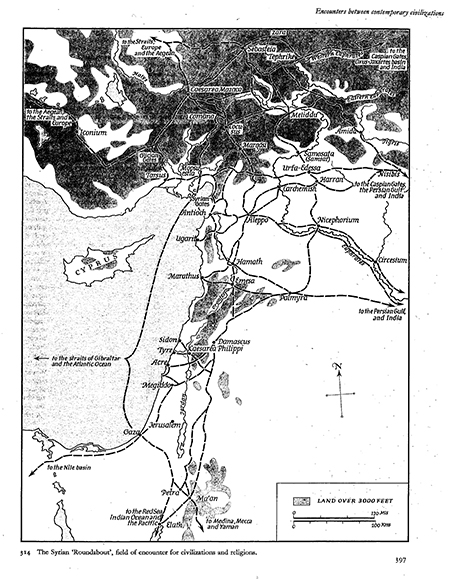

Toynbee’s reputation soon plummeted when historians turned away from big ideas to nibble at small-scale trends. But Toynbee’s unique perceptions still leap to mind. Today, we recall his remarkable recognition of historic geostrategy: that “two relatively small patches of geography” – one in “the Oxus-Jaxartes basin,” i.e. Afghanistan, and the other in Syria, have been “Roundabouts” where traffic from any point of the compass can be switched to any other point in alternative combinations and permutations as civilizations and religions jostle and collide at exceptionally close quarters.2 This “Caravan” features the Syria Roundabout.

Simply to list the disruptive forces – “the traffic” in Toynbee’s term – now jostling one another in the Greater Syrian space is to know how each holds potential for shoring up or battering down one or another elements of international order. Three categories stand out:

The state as the fundamental unit of world affairs. With the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and Caliphate after the First World War the entire Middle East region was brought on course to enter the modern international state system. If that structure is collapsing, world order as a whole is jeopardized. The possibilities reveal the stakes: what of America’s long commitment to the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Lebanon? Can Saudi Arabia define itself as a true state rather than a tribal royal family? Iran’s double game of playing a legitimate state role while pursuing its revolutionary ideology has been exposed, but not repulsed even as it accelerates preparations to attack Israel from Lebanon. Can Iraq be guided to relative stability as a reformed state encompassing Shia and Sunni and protective of minorities? Should the Kurdish people establish a state? Autonomy short of statehood has served the Kurds well; declaration of a Kurdistan could arouse the dogs of war on every border of such a new state. The maelstrom of these forces is Syria: even if the state borders of Syria are re-affirmed, the likelihood of even more horrific layers of war with big power involvement is mounting.

International Conventions. The Roundabout exercises a centripetal pull, drawing violations of major international agreements toward it, then spinning them out centrifugally to infect other parts of the region and beyond. Iran’s 2015 “deal” with the U.S. has made Tehran a de facto threshold nuclear weapons state while failing to constrain its advances in ballistic missile technology or its omnidirectional undermining of regional order. The Syrian Roundabout has been used by Iran to extend a form of neo-imperial sphere of influence in a corridor to the Mediterranean, further enhancing its nuclear weapons-power profile. Other regimes in the region now must consider whether to match Iran’s nuclear breakout. If left unaddressed, Iran’s nuclear program will mean the end of the Non-Proliferation Treaty, one of the pillars of the international system. Is the idea of a Nuclear Free Zone for the Middle East on the order of the 1967 Latin American Treaty of Tlatelolco an utter impossibility?

The Assad regime’s repeated use of chemical weapons and its continuing possession of a variety of CBWs after the U.S. “red line” was not enforced and Russia stepped in to claim that all such weapons had been located and collected, is demonstrating that the Chemical Weapons Convention of 1993 is being rendered nugatory by the Syrian War. Evidence that North Korea is linked to the Assad regime’s use of chemical weapons reveals that the Roundabout’s spin-off effect can reach around the world.

The Genocide Convention also has been mocked by the course of seven-plus years of conflict in Syria. The numbers of killed exceeds one-half million with several million displaced or in refugee flight through the region and beyond, amounting to the most extensive human disaster since the Second World War. The language of the Genocide Convention was so specifically drawn as to make it easy for governing authorities to conclude that virtually no major human cataclysm precisely falls under the Convention’s terms. Now, when international commitments so evidently require renovation and enforcement, they instead are circumvented and openly defied.

And the fundamental principle of the Laws of War – that states must field professional militaries – repudiated by Russia in Ukraine was even more blatantly violated by Russia’s battalion-sized unmarked attack on the U.S. base at Deir al-Zor in early February.

Alliances. The Roundabout War which began in 2011 has drawn in Russia, Iran, Turkey, Iraq, the Kurds and an array of factions. A second Roundabout War is in the offing and likely to add Israel, Lebanon, Jordan, the Gulf Arab states, and others. As dangers gather and threats expand, the question of alliances is paramount. There is no current alliance-category relationship of the U.S. in the Middle East that does not urgently call for restrengthening, reappraisal, revival, or revision. If the very concept of America’s alliances is not shored up, deterrence will fade, partners and friends will make new accommodations, and the chances of avoiding a new, wider war will vanish. While Turkey remains in NATO, President Erdogan is shaping new quasi-alliance relationships with Russia and Iran. The possibility of a “great alliance shift” with grave consequences for Asia as well as the Middle East, will worsen.

The “Caravan” series increasingly has revealed that tensions and conflicts in the Middle East have a significantly negative impact on larger world order. Turbulence from the current Syrian Roundabout has pulled outside powers into the region’s conflicts and made power rivalries with wider war a dangerous likelihood. The U.S., for its own national interest as well as the survival of the modern international state system, must take on this primary responsibility.

[1] 1 William H. McNeill, Mythistory and Other Essays. U. of Chicago, 1986, 127.

[2] 2 Arnold Toynbee, A Study of History, revised and abridged, Portland House, 1988, 195-6.