- Economics

- Answering Challenges to Advanced Economies

This essay is drawn from a presentation to the Hoover Economic Policy Working Group on tariffs. Read more about the working group’s research here.

There are many reasons to fear President Trump’s tariffs, his efforts to manage interest rates and the US dollar, and his initiatives to dramatically cut the United States’ global financial and diplomatic roles to achieve his worldview. If fully implemented, Trump’s original tariffs and other initiatives would materially harm US and global economic performance and upend the world order, with the United States playing a more isolated role.

Fortunately, based on Trump’s past behavior and willingness to negotiate lower tariffs, our scenario analysis leads us to believe that the highest-probability policy outcome will involve significantly lower average effective tariffs than originally proposed and even below those in force today, and that the US economy will continue to expand and lead the world. However, the president’s erratic policy-making and belligerence toward allies has already dented US credibility and will cause lasting harm to important global relationships that will take years to repair.

Built upon misunderstandings

Economic theory and common sense reveal the flaws in President Trump’s advocacy of tariffs, and history overflows with evidence that tariffs harm economic performance and fail to achieve their goals. Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations and David Ricardo’s Law of Comparative Advantage refute the doctrine of mercantilism, the perceptions of the world as a zero-sum game, and the objectives of maximizing the balance-of-trade surplus.

Trump’s notion that tariffs will generate sufficient revenues to improve US government finances is wildly unrealistic. During the nineteenth century, tariffs generated a large portion of revenues when government finances were small and before income taxes were established in 1913. Today, tariffs would depress income-tax receipts by harming the economy and corporate profits, and would fail to improve deficit financing. Trump’s hope of returning to the mid-twentieth-century era of labor- and capital-intensive US manufacturing also ignores massive technological advances as well as the United States’ comparative advantages, particularly its strength in high-tech services.

While Trump’s point that manufacturing is necessary for national security may have some validity, he does not distinguish between national-security-oriented manufacturing and manufacturing unrelated to security, and his hope of bringing manufacturing jobs back home is economically naive. He overstates US leverage in imposing and negotiating tariffs while understating retaliation and the adverse impacts of tariff-imposed weakness on global trade and global economies. Above all, Trump understates the negative consequences, both economic and diplomatic, of a significant shift toward US isolation and alienation of its allies.

The risks of isolationism

Consider the current threats of high tariffs in a historical context. The free-trade movement in the United Kingdom, initiated with the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 and the Cobden-Chevalier Treaty of 1860, ushered in the first era of globalization and a significant rise in international trade. This boom facilitated and contributed significantly to the industrial revolutions in the United Kingdom and subsequently the United States. Global trade soared as a share of global GDP. (Of note, the United States ran a trade deficit nearly persistently from 1865 through World War I, and the associated dramatic rise in capital inflows was critically important to its development into an industrial power. Foreign capital providers enjoyed high rates of return on their investments in dollar-denominated assets, contributing to and benefiting from the strong productivity gains.) The United Kingdom and Europe were benefiting as well.

This economic boom was also driven by sizable immigration to the United States, whose foreign-born share of the population increased significantly. But there was mounting resentment and pushback over this growing population of immigrants, and this fed popular support for heightened controls on immigration, global trade, and cross-border capital flows. Industrialization also was perceived as a threat by entrenched European landholders.

Restrictions on global trade and capital flows were ramped up during World War I, beginning an extended era of US protectionism. New laws sharply curtailed the flow of immigrants, and the foreign-born share of the US population began to fall. The Fordney-McCumber Tariff Act of 1922 imposed tariffs of 14 percent on all imports into the United States. At the onset of the Great Depression, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act imposed effective tariffs of 20 percent on imports. This accentuated the severity of the economic contraction and initiated a period of declining international trade and capital flows as a percent of GDP, along with a sharp reduction in the share of foreign-born citizens in the US population.

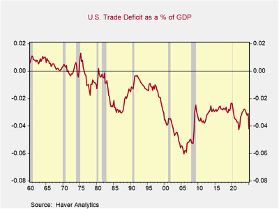

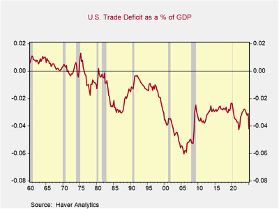

The second era of globalization began after World War II and gathered steam until the Great Financial Crisis of 2008–9. Global trade and growth boomed, and the portion of people worldwide living in poverty shrank dramatically. The United States was a major beneficiary. It had a nearly persistent trade deficit beginning in the 1970s (figure 1), and benefited tremendously from the associated capital inflows that helped finance technological innovations and economic advances.

The United States initiated many critical international reforms that promoted global trade and capital flows, including GATT, Bretton Woods, the IMF, and the World Bank. Notably, in 1999, the United States promoted China’s acceptance into the WTO, which afforded it favored-nation status and lower trade barriers. China’s subsequent emergence as the world’s largest hub of manufacturing and the leader in global trade and growth, with its very large bilateral trade surplus with the United States, has been a primary focus of President Trump’s tariff policies, both in his first term and today.

- US trade deficit as percentage of GDP

During the second era of globalization, not all nations reduced their tariffs and barriers to trade, and these that erected such barriers paid the price in economic growth and progress. The best examples of laggards are India and Argentina, along with other less-developed nations. Jawaharlal Nehru of India believed in import substitution, and India maintained high tariffs and barriers to trade from the 1940s to the 1990s. Raúl Prebisch of Argentina pursued the same approach from the 1930s to the 1980s. These countries’ economies stagnated and their citizens paid the price.

Manipulating the dollar

In addition to imposing high tariffs, President Trump favors intervening in markets to achieve desired outcomes for the dollar and interest rates. His goals are potentially inconsistent and his methods of achieving them undercut the tenets of free enterprise and smoothly functioning markets. Trump wishes to maintain the US dollar as the world’s reserve currency but favors a weaker dollar that would support US exporters and wants lower interest rates. He has threatened to pressure the Federal Reserve’s conduct of monetary policy to achieve his objectives.

Trump proposes initiatives that would give the United States a more isolated role in the world, and he envisions a change in the world order. This has jarred international relations and turned natural allies against the United States. It has raised concerns about a loss in US government credibility and reliability, as reflected in a marked decline in the dollar.

Trump’s earlier announced tariffs would likely have generated a recession in the United States and harmed global economies and trade. Fortunately, his twists and turns have resulted in a significant easing of average effective tariffs. In particular, recent negotiations with China have lowered reciprocal tariffs, at least temporarily. Further bilateral negotiations with other nations are expected.

The impacts of these sweeping tariffs remain uncertain. The global backdrop is a resiliently healthy US economy, soft economic growth in Europe and Japan, and the beginning of a recovery in the UK. China’s domestic economy has been decidedly weak, as consumers are saving rather than spending to repair their balance sheets after the Chinese real estate collapse. Economic forecasters have tilted toward, at minimum, a transitory rise in inflation; they also worry about rising inflationary expectations and forecast recession in many advanced economies including Europe, the UK, Japan, Canada, and Mexico, and sharply slower growth in China.

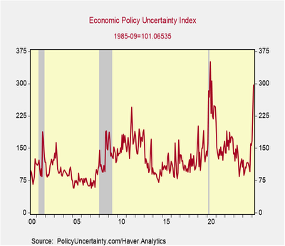

The tariffs are expected to distort global supply chains and production inefficiencies and will probably elicit foreign retaliation, thus creating a larger negative than corporate taxes of the same magnitude. In addition, the spike in uncertainty related to Trump’s erratic policies and hard-to-predict public statements is likely to reduce business investment and consumer spending. There has been a surge in the closely followed Baker-Bloom-Davis Economic Policy Uncertainty Index, which its developers show is empirically correlated with consumption and industrial production (figure 2).

- Baker-Bloom-Davis Economic Policy Uncertainty Index

Trump’s tariffs and related uncertainties add an extra layer of risk when analyzing persistent budget deficits and rising government debt. Concerns about the loss of US government credibility and rising debt create a toxic mix, potentially jeopardizing the longstanding role of US Treasuries as the world’s safe-haven asset. Currently, nearly one-third of the outstanding publicly held debt of $26 trillion is held by foreigners, and a sharp decline in the demand for US Treasuries could drive up bond yields. Moody’s Ratings has in fact downgraded US government debt, joining Fitch Ratings (in 2023) and S&P Global Ratings (in 2011).

Another concern is the looming collision between Trump’s tariffs and the Federal Reserve’s dual mandate. Inflation is currently above the Fed’s target of 2 percent inflation and employment is close to maximum, with a jobless rate of 4.2 percent. The Fed is publicly committed to lowering inflation to its target and understands that the tariffs should impose only a one-time boost to the general price level, but it worries about a rise in inflationary expectations that may become embedded in wage- and price-setting behavior. Recent announcements by Walmart and other firms that they will be raising prices in response to the tariffs amplify such concerns. Trump’s public and private statements convey the disquieting message that he should have more influence over the Fed’s monetary policy.

Trump did ease up on his tariffs in April, when a sharp decline in the stock market and the US dollar crossed the president’s pain threshold (or the pain threshold of Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, who had spent a career in financial markets). This revealed a great deal about the administration’s approach to policy-making—chiefly a willingness to negotiate tariff exemptions with global leaders as well as American business leaders bearing incentives such as pledges of higher capital spending and shifts of production back to the United States.

Is there a “least-worst” scenario?

President Trump’s use of tariffs as a weapon to achieve many objectives, his policy reversals that respond to pain thresholds, his enthusiasm for bilateral negotiations with significant trading partners, and his encouragement of “kiss the ring” cronyism are misguided and distasteful. Worse, they show a naive disregard for free enterprise and markets. Nevertheless, they are a useful guide to sketching different policy outcomes and their consequences. Note that all of the following scenarios involve different degrees of “worse”—because the best economic outcomes would follow from free trade without tariffs or other barriers.

The scenarios are:

Scenario 1. Best outcome: mild negative. 10 percent average effective tariffs on all imports, with select exceptions (compared to 4 percent before Trump); negotiations reduce trade barriers, uncertainties are moderate; significant US slowdown or very mild recession; dollar and stock market remain firm and Treasury yields decline. Probability: 10 percent.

Scenario 2. Less-worse case. Tariffs decline to 12–14 percent average effective rate (roughly $140 billion or 1.4 percent of GDP), including negotiated lower tariffs for Canada and Mexico; diminished retaliation; uncertainties diminish from current levels; distortions to supply chains and production processes result in a marked economic slowdown or mild recession; Fed eases and provides support to stock market; dollar declines modestly in an orderly fashion; United States retains dominant status in world. Small but cumulative impact on US longer-run potential growth. Probability: 70 percent.

Scenario 3. Worse case. 20 percent average effective tariffs, including 10 percent on all imports, easing of current tariffs on China (50 percent), Canada, and Mexico; fall in US dollar results in spike in US Treasury yields that forces Fed intervention to stabilize markets; sizable stock market declines; moderately deep recession with sizable hits to business investment and housing activity; sizable negative impact on US potential growth (-0.3 to -0.4 percent). Probability: 15 percent.

Scenario 4. Worst-worse case. Effective average tariffs of 25 percent. Trade war with China escalates and current tariffs on Canada and Mexico persist; Trump ramps up deportation of immigrants and makes permanent cuts in government funding of research and universities; US credibility diminishes markedly, significantly reducing value of dollar and isolating US economically and diplomatically; stock market falls sharply; deep recession and potential growth diminished by 0.5 percent; US exceptionalism erodes decidedly. Probability: 5 percent.

Placing the highest probability on the less-worse scenario seems realistic based on the president’s reported behavior and preferences. But repairing relationships with allies and achieving diplomatic normalcy may take years of good US behavior, which may not be forthcoming during the Trump administration. Our hope is that with an easing of tariffs and trade barriers, foreign leaders will “tolerate” Trump, while continuing to appreciate the exceptional capabilities and potential of the United States’ private sector and economy.