- Contemporary

- International Affairs

- History

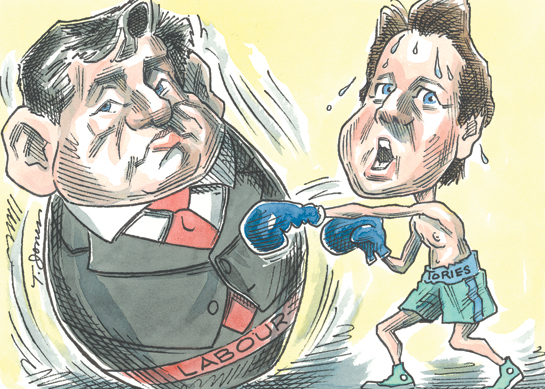

The story of Britain’s coming election may not be as simple as it appears. Most pundits expect the Conservative Party, led by David Cameron, to win, returning to office for the first time since 1997. For most of the past two years, the Conservatives have enjoyed a lead of 5–10 points in the polls over the incumbent Labour Party, led by Prime Minister Gordon Brown. But there is a chance that the spring election might not produce a majority government at all. Instead it might, for the first time in decades, produce a fragile minority, even a coalition, government.

A 5- to 10-point lead is substantial for any party going into an election campaign in a democratic system. So why is this Conservative lead not conclusive? There are two reasons.

The first is that recent demographic shifts in the British population, reflected in changes in the boundaries of election districts, give a decided statistical advantage to the incumbent Labourites. The second is that although the Labour government is unpopular (as is Prime Minister Brown) after thirteen long years in power and is struggling with an awful recession, polls show that the Conservative Party is not well trusted or popular either.

The PARLIAMENTARY System

British voters going to the polls on Election Day have only one vote to cast, for their local member of the House of Commons (members of the upper house of Parliament, the House of Lords, are appointed, not elected). They do not vote for prime minister.

The prime minister is appointed by the queen, who, as constitutional monarch, is obliged to choose the leader of whatever political party has won the most recent election. All party leaders are chosen by a combination of the votes of their fellow members of Parliament plus citizen members of their respective parties around the country. So Britain’s prime minister is “elected” only indirectly.

One other feature of the British election system is potentially important at each election: Britain has a major, permanent third party, the Liberal Democrats. The Lib Dems, as they are called, have not won an election and formed a government since the early twentieth century, but they do regularly receive 20–25 percent of the vote. As a result, they currently hold more than sixty seats, roughly 10 percent of the House of Commons. Further, support for the Lib Dems often comes from protest voters who are angry or disillusioned with the major parties; in this regard, voter behavior is difficult to predict. The Lib Dems thus have real potential to affect the formation of governments, although they usually do not realize their potential because one party almost always emerges with a majority.

If no party wins a majority of the seats, as has happened occasionally, the Lib Dems can be decisive in determining which major party will take office.

Labour’s statistical advantage

Because of recent geographic shifts in population, as charted in Britain’s latest census and acknowledged in a redistribution of seats by a nonpartisan Boundary Commission, Labour enjoys a more efficient distribution of its usual voters around the country. The details of this statistical advantage are highly involved, but the bottom line is that Labour would need about 6 percent fewer votes than the Conservatives to win a majority of seats in the coming election. Thus Labour could receive significantly fewer votes than the Conservatives and yet hold on to power!

So, what happens if the Conservative lead shrinks as the election approaches, as it does in most British campaigns? For example, even in Tony Blair’s fabulously successful elections of 1997 and 2001, the final vote for Labour shrank more (about 3–4 percent) than the political polls had suggested. If that scenario were to play out again this year, and the slippage were even across the country, the Conservatives’ hoped-for majority could be in trouble.

WHAT DO THE VOTERS WANT?

Another variable is the electorate’s willingness to support a Conservative return to government after thirteen years in the political wilderness. The fourth straight term of the most recent Conservative government (eighteen years in power, no less) ended in a shambles and led to a disastrous 1997 defeat. Scandal, corruption, a sense of ineffectiveness, and pure fatigue with the same old leaders plagued the Conservatives. The last Conservative government can be said to have suffered from a kind of political geriatric malady typical of all governments long in power. Labour is working hard to remind voters of what it was like during the Conservatives’ last government. Will its efforts drive down support for Conservatives far enough to allow Labour to wield its statistical voting advantage?

There is a tantalizing hint in the results of the 1992 election. In that case, the situation was reversed politically, but the details were similar. The Conservatives had held power for thirteen years straight; their government was largely unpopular in the midst of a recession; their monumental prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, had been replaced by the much less impressive John Major—but the Conservatives won anyway. Today, the monumental Tony Blair is gone; the Labour government is unpopular in the midst of an even worse recession; and Blair has been replaced by the much less impressive Gordon Brown.

A close examination of that 1992 upset election by scholars and polling organizations shows that at the last minute voters recoiled at the prospect of returning Labour to power, thanks to the Conservatives’ remarkable job during the campaign of reminding voters how badly Labour had done in dealing with the economy during its last time in office. They also had vividly reminded voters of Labour’s ineptitude in handling a disastrous series of union strikes in 1978–79 known infamously as the “Winter of Discontent.”

Can Labour do to the Conservatives in 2010 what the Conservatives did to Labour in 1992? Most current polls do not favor a Labour success, except for one category of questions: although voters seem to be more confident that the Conservatives can better handle a range of specific policy issues than Labour, they do not think that the Conservatives “feel” their pain in the recession or relate sympathetically to the range of troubles that middle-class families are suffering. Conservatives are not as trusted as Labour. This could be an opening for Labour, under the right circumstances and in a campaign that emphasizes class differences, as Labour intends to do.

The question of class is much debated. Clearly, the importance of class has declined during the past few decades as Britain has become more affluent. But amid the current recession, it has returned to some as yet unknown degree. Labour’s problem in using this issue, of course, is the problem of incumbency. Although voters may see Labour as more in tune with their plight, Labour will find it hard to escape blame for the current state of affairs.

an unsettled Outlook

The Conservatives are clearly still favored to win the election with a majority, allowing Cameron to become the new prime minister. But there is a chance that the Conservative lead could shrink on polling day to a level that would produce a “hung Parliament” without a winner, yielding a minority or even a coalition government. This would probably lead to yet another election within a year or so (British elections do not occur at a fixed time, only within a five-year period and whenever the sitting prime minister decides to call one).

But more important, a hung Parliament leading to another or even multiple elections would cause Britain to live through a period of unstable government, in sharp contrast to the nearly thirty years in which the two major parties have enjoyed long periods in office amid the best British economy in a hundred years. All in all, there might be difficult times ahead in British politics.