- World

- Military

- History

|

| Wedemeyer as a major general on the War Department’s General Staff, ca. 1943.

|

The Hoover Institution Archives contains the personal papers of many of the past century’s most notable public figures. Of these figures, few are more timelessly interesting than U.S. Army general Albert Coady Wedemeyer.

The distinguished British military historian John Keegan judged Wedemeyer "one of the most intellectual and far-sighted officers America has ever produced." Yet Wedemeyer almost flunked out of West Point and finally ranked 15th from the bottom in his class of 284 cadets.

Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten found Wedemeyer, his plans officer in the Southeast Asia Command in World War II, a noble and gracious gentleman. On the other hand, General "Vinegar Joe" Stilwell of the U.S. Army called him "the world’s most pompous prick." Stilwell derided Wedemeyer as a "headquarters" type of soldier, whereas General George S. Patton Jr. praised him as a "fighting man."

Even more puzzling to some was the example of a soldier’s soldier who, in his later years, became a sharp critic of his country’s policies and policymaking.

In viewing the scope of Wedemeyer’s extraordinary career, one is reminded of "Pug" Henry, the sturdy naval protagonist of Herman Wouk’s World War II novels The Winds of War and War and Remembrance, who had a special talent for being near the action. Cruising as confidently through the seas of high politics and diplomatic intrigue as on blue water, Pug turns up in an unlikely variety of places: navy headquarters in Washington, the White House, the chancellery of the Third Reich in Berlin, the bowels of the Kremlin, Pearl Harbor after the debacle, the scenes of the great naval battles of Midway and Leyte Gulf, islands of the far Pacific, Soviet army headquarters on the Eastern front, and Teheran in the Middle East. He plans operations, commands warships, excels at strategic intelligence, and undertakes secret missions for commanders in chief. In the course of his eventful career, Pug meets, advises, or links arms with many of the war’s leading actors, including Franklin Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, Josef Stalin, and Adolf Hitler.

Pug Henry is, of course, a fictional character. One real-life American officer, however, actually touched many of Pug’s far-flung bases, hobnobbed with most of the same famous people, and played a considerably more significant role in planning and managing the Allied war effort. That officer was Albert Wedemeyer.

Wedemeyer served in countless corners of the globe, including Washington, Berlin, London, Manila, New Delhi, and Chungking. He played important roles in both the Atlantic and Pacific areas, and he came into personal contact with war leaders on the highest levels. Those leaders included, on the American side, President Roosevelt, Harry Hopkins, cabinet officers, the chiefs of staff, and senior field commanders; in Britain, Prime Minister Churchill and top members of the government and military establishment; in China, President Chiang Kai-shek, Chairman Mao Tse-tung, and Chou En-lai; in Germany, General Ludwig Beck (army chief of staff) and Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg (leader in the 1944 anti-Hitler plot); and, from the Soviet Union, Andrei Gromyko.

The Cadet

The foundations of Wedemeyer’s career were laid in the small-town atmosphere of Omaha, Nebraska, where he was born in 1896. His father was the son of a Union veteran of the Civil War and a sometime military man himself. His mother’s father had also been a soldier in the Civil War, as well as in the Mexican and Indian wars.

Young Albert had early set his heart on a career in medicine but eventually decided to follow the example of many of his contemporaries and try his hand at soldiering. In 1917, he went east to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point.

Wedemeyer henceforward regarded West Point as one of the supreme experiences of his life, and his wholehearted devotion to the ideals of the institution never wavered. The First World War temporarily foreshortened the West Point curriculum, with the result that the class of 1921 sped through the academy in less than two years and was redesignated the class of 1919. Wedemeyer was commissioned in the infantry and entered a long apprenticeship in the peacetime army.

|

| Lieutenant Wedemeyer as an aide-de-camp, late 1920s.

|

A Long Apprenticeship: The Interwar Years

Life in the neglected U.S. Army of the interwar years is often portrayed as routine, dull, and unchallenging. Although promotion was indeed slow (Wedemeyer and his classmates remained lieutenants for almost 17 years), Wedemeyer seems to have found challenge and opportunity in every post and duty. His record as a junior officer reflected a sustained pattern of soldierly excellence. Troop and staff duties at various stateside posts were interspersed with tours in the Philippines in the 1920s and in China in the early 1930s. Rating officers commented repeatedly on the "high ideals" he not only professed but sought earnestly to embody; his energy, initiative, and devotion to duty; the breadth of his interests; his effectiveness as an instructor; and his capacity to inspire and motivate his soldiers. One commander described him as "the most efficient and loyal lieutenant with whom I have ever served." A fine military bearing and social graces contributed at the same time to his assignments as aide-de-camp to several general officers—assignments that greatly enhanced the educational value of those years.

A turning point in Wedemeyer’s career came in 1934, when the well-seasoned lieutenant returned from a second tour in the Far East to attend the army’s Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. This important assignment afforded Wedemeyer an opportunity to transcend his undistinguished academic record as a cadet, and he made the most of it. During the exercises that marked the end of the two-year course, the school placed him in command of the friendly "blue army" (the enemy army was traditionally depicted in red symbols on the situation maps)—a sure indication that he stood academically at or near the top of his class.

The years at Leavenworth sharpened Wedemeyer’s military skills, especially in the command and tactics of large field organizations. He realized the full benefits of that work in his next assignment, which was also primarily academic. In the fall of 1936, the War Department sent him on a two-year tour as an exchange student at Germany’s historic military college (the Kriegsakademie) in Berlin. Germany was engaged at the time in an all-out program of rearmament under the National Socialists. Its armed forces were expanding rapidly and introducing revolutionary new technologies and doctrines that soon would make the Wehrmacht one of the most formidable military machines in history. The firsthand insights into these developments gained by Wedemeyer in Berlin were reported on his return in a 147-page document that described in careful detail the organization, equipment, tactical doctrines, and morale of the developing German forces. "For political and economic reasons," Wedemeyer wrote,

This report was subsequently applied to good effect in the organization and training of the U.S. forces that fought World War II. In a note to President Roosevelt written soon after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson declared that, without the timely analysis of blitzkrieg provided by Wedemeyer, "we should be badly off indeed."

|

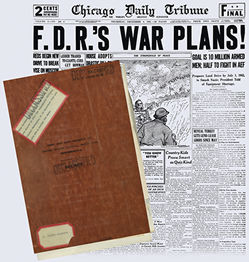

| In one of the most famous press leaks in American history, the most sensitive parts of the Victory Plan appeared in the nation’s press—in almost verbatim form—on December 4, 1941, only three days before Pearl Harbor. Click to view the larger image.

|

War Looms on the Horizon

On his return from Germany in 1938, Wedemeyer briefed—and favorably impressed—the General Staff (including the chief of war plans, Brigadier General George C. Marshall) on his experiences in Berlin. Then, at his own urgent request, he was assigned to troop duty at Fort Benning, Georgia.

In the meantime, war had begun in Europe, and by the middle of 1940 Hitler’s armies had overrun all of Western Europe. On the other side of the globe, an aggressively expansionist Japan continued its war in China and pressed its claims in South and Southeast Asia. In September 1940 Wedemeyer was recalled to the War Department in the grade of major. In the spring of 1941 he was assigned, on instructions of General Marshall (who had become chief of staff), to the War Plans Division of the General Staff.

It was in this assignment that Wedemeyer first made a name for himself as a strategist and planner of the first rank. With U.S. war programs burgeoning erratically in response to ever-expanding threats, the need for coherent policy guidance gradually became obvious. In July 1941 President Roosevelt asked the secretaries of war and navy for an estimate of the total productive effort the nation would need in the event of war to ensure victory over all its potential enemies. In the War Department, the responsibility for preparing a reply to this most nebulous and challenging of inquiries was eventually assigned to Major Wedemeyer. By late September he had assembled a voluminous and prophetic document, the famed Victory Plan—a broad blueprint for U.S. participation in a possible war against the Rome-Berlin-Tokyo Axis.

|

"In a note to FDR shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson declared that, without the timely analysis of blitzkrieg provided by Wedemeyer, ‘we should be badly off indeed.’" |

The Victory Plan envisioned the recruitment of some 10 million men into the armed forces, along with the unprecedented development of industrial capacity to arm and support such a force in combat by mid-summer 1943. It assigned strategic priority to the defeat of Hitler in Europe—and accordingly accepted an initially defensive posture for the Allies in the Pacific. It proposed a massive buildup of Allied strength in the British Isles, an early cross-Channel invasion of continental Europe, and a combined arms drive across northern France into the industrial heart of Germany. Wedemeyer’s plan stated that,

Irrespective of the nature and scope of [our] operations, we must prepare to fight Germany by actually coming to grips with and defeating her ground forces and definitely breaking her will to combat. Such requirement establishes the necessity for powerful ground elements, flexibly organized into task forces that are equipped and trained to do their respective jobs. . . .

The important influence of the air arm in modern combat has been irrefutably established. The degree of success attained by sea and ground forces will be determined by the effective and timely employment of air supporting units and the successful conduct of strategical missions. No major military operation in any theater will succeed without air superiority, or at least air superiority disputed.

The necessity for a strong sea force, consisting principally of fast cruisers, destroyers, aircraft carriers, torpedo boats, and submarines continues in spite of the increased fighting potential of the air arm. Employment of enemy air units has not yet deprived naval vessels of their vital role on the high seas, but has greatly accelerated modern methods and changed the technique in their employment. It appears that the success of naval operations, assuming air support, will still be determined by sound strategic concepts and adroit leadership.

After Pearl Harbor, this plan served official Washington as the basic guide for mobilizing U.S. manpower and industry and for structuring and deploying the armed forces.

|

| Allied commanders in Southeast Asia plot the war, late 1944. Standing: Major General Wedemeyer, commanding China theater; seated, left to right: Lieutenant General Daniel I. Sultan, commanding Burma-India theater; Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, Supreme Allied commander, Southeast Asia Command; and Major General William J. ("Wild Bill") Donovan, chief of U.S. Office of Strategic Services.

|

The War Years

The early war years brought Wedemeyer rapid promotion (he rose from major in September 1941 to brigadier general the following July) and ever-broadening responsibilities. As chief of the Strategy and Policy Group in the War Department’s powerful Operations Division, he played an important role in planning and managing the war. When President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill met with their staffs in Washington, London, Casablanca, Quebec, Cairo, and elsewhere, Wedemeyer was regularly on hand to assist General Marshall in presenting and defending American proposals. In the prolonged debates over grand strategy that developed, and especially in disputes with the British over the timing and nature of the second front in Europe, Wedemeyer remained a firm advocate of a rapid concentration of force in Britain, an early cross-channel invasion of the Continent, and decisive battle. He accordingly regarded the campaigns in the Mediterranean area—first into North Africa, then across the water to Sicily, and finally up the rugged boot of Italy—as unwise diversions.

Although Wedemeyer had tentatively been promised a field command in the climactic battle for Europe, his future lay elsewhere. At the Quebec Conference in the late summer of 1943, the president and the prime minister decided to establish a new command in Southeast Asia to better coordinate Allied efforts in that area. Admiral Lord Mountbatten was designated supreme commander of this new Southeast Asia Command (SEAC), with headquarters in New Delhi. Wedemeyer was assigned, on British suggestion, as the officer in charge of plans. He thus found himself half a world removed from the scenes of the major action he had done so much to plan. Instead of fighting the primary enemy, he was drawn into the tangled affairs of a combined command in an exotic, far-off theater of relatively low strategic priority. (After the Normandy beachhead was secured in June 1944, General Marshall telegraphed Wedemeyer in India with the news that "your plan has succeeded.")

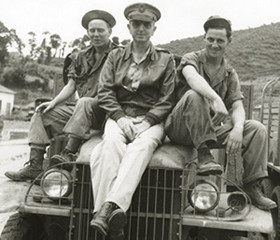

China provided the setting of Wedemeyer’s next assignment—and the subject with which his career would thenceforward be permanently linked. When U.S. general Joseph Stilwell was recalled from command of the China-Burma-India theater in October 1944, Wedemeyer was relieved of his duties at SEAC and dispatched to Chungking. There he assumed command of the newly established China Theater of Operations (a U.S. command) and was named chief of staff in the Allied command structure to Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, the president of China. In these capacities he succeeded in stemming a major Japanese land offensive in China. At the same time he developed constructive working relations with the government of China, improved the effectiveness of the Chinese armed forces, and laid plans for further operations against the Japanese. Japan’s surrender in August 1945 closed the book on many of these concerns.

|

| Wedemeyer addresses graduates of a Chinese officers’ training course, early 1945.

|

Debacle in China

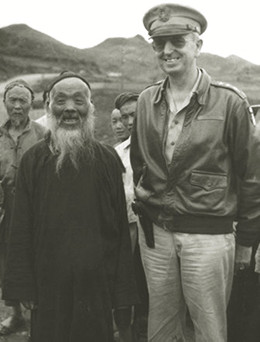

Unfortunately for the war-weary people of China, the defeat of the foreign invader brought not peace but the resumption of mortal civil strife between Communist insurgents under Mao Tse-tung and the Nationalist government forces of Chiang Kai-shek. This situation presented U.S. policymakers with an awkward dilemma, for to continue support of our wartime ally, Nationalist China, in such war-related tasks as the repatriation of Japanese soldiers and the reestablishment of control over previously occupied territory inevitably meant taking sides in a civil war. Wedemeyer, who had observed Chinese affairs at close range for almost a year, concluded that the Nationalist-Communist split was irreparable. He accordingly recommended increased U.S. support (short of deployment of U.S. combat forces) of the Nationalist government, and warned of an imminent Communist triumph in the absence of that support. Despite all its manifold faults and problems, he argued, the Nationalist government represented China’s—and the world’s—best hopes for peace.

|

| Wedemeyer enjoys a light-hearted moment with a Chinese sage, China, 1945.

|

Contrary to Wedemeyer’s recommendations, however, Washington opted for a policy aimed at unifying China by reconciling the contending factions. To implement this policy, President Truman sent recently retired General Marshall to China as ambassador with the mission of bringing the Nationalist and Communist Parties together in a coalition government and integrating their armed forces. When these efforts failed at the end of 1946, armed conflict resumed with heightened intensity. Wedemeyer was relieved of his Chinese duties in September 1946 and assigned stateside to command the Second U.S. Army. In July 1947 President Truman again dispatched him to the Far East to assess the unfolding crisis. And again Wedemeyer recommended (doubtless contrary to Washington’s expectations) continued support of the Nationalist government. As the situation deteriorated, U.S. policy nonetheless remained ambivalent, and by late 1949 the Communists had emerged victorious in mainland China.

When the Cold War came to dominate world affairs in subsequent years, the question of "who lost China" became a bitterly divisive issue in U.S. domestic politics. Wedemeyer conceded that China was not "ours to lose" but insisted that indecisive and misguided U.S. policy had helped push it over the brink. He lived to see the Republic of China on Taiwan—the nation established and led by President Chiang Kai-shek and many of the individuals whose aims, abilities, and good faith he had come to trust on the mainland—develop a spectacularly free and successful economy and an increasingly free and stable political democracy. This achievement he often contrasted with the course of events under the Communists on the mainland.

|

| Wedemeyer, as commanding general, China theater, poses with two GIs in Kweiyang, Kweichow province, July 1945.

|

Cold Warrior

After returning from China in 1947, Wedemeyer went to the War Department General Staff, where he served for a year as director of the Plans and Operations Division and for a second year (in a reorganized Department of the Army) as deputy chief of staff for plans and combat operations.

These years in the postwar Pentagon proved less than satisfying for strategist Wedemeyer; indeed, they were generally distressing. He found that the newly "unified" defense establishment was riven by angry controversy over service roles and missions; that the severe budgetary constraints of the period exacerbated interservice conflict and threatened the effectiveness of the operating forces; and that defense organization at the highest levels was obviously weak. Most troubling of all, however, was the spectacle of the free world again beset by a totalitarian aggressor. Having just fought and won a great war at enormous cost to rid the world of tyrants, we now faced another—perhaps more dangerous—tyrant in the form of our wartime ally, the Soviet Union. It had been prudent, Wedemeyer agreed, for the Western democracies to make common cause with Stalin to defeat Hitler; it had been folly, however, to suppose that Stalin’s goals in the postwar world would be compatible with our own. As one who believed (with Clausewitz) that wars should be guided by political ends and that the achievement of those ends was the proper measure of success, Wedemeyer was convinced that U.S. war policy had been seriously flawed. In his postwar role, he placed great emphasis on the importance of strategic vision and historical insight in national security policymaking.

Most of official Washington’s attention during these postwar years was distracted, however, by the rapidly unfolding crises of the Cold War. The Truman Doctrine was proclaimed and the Marshall Plan was launched in 1947; the Berlin airlift was undertaken in 1948; the North Atlantic Treaty was signed and Nationalist China finally fell in 1949. Wedemeyer, having incurred the displeasure of his old boss General Marshall (then secretary of state) because of his stand on China, and finding himself philosophically out of step with some of his army colleagues, left the Pentagon in August 1949 to assume command of the Sixth U.S. Army headquartered in San Francisco. Only a few months later, the United States found itself once more embroiled in a hot war, this time with North Korea and Communist China. Although Wedemeyer was by no means averse to the use of force to resist aggression, he deplored the fact that we had committed ourselves to a land war in Asia and that we had done so quite unprepared and with little or no forethought. It struck him as bitterly ironic that the occasion for this armed intervention would never have arisen in the first place had China remained in hands friendly to the West.

|

| President and Mrs. Reagan welcome General Wedemeyer to the White House to receive the Presidential Medal of Freedom, May 23, 1985.

|

Distressed by what he perceived as the erratic patterns of U.S. policy, and believing his own usefulness as a soldier at an end, Wedemeyer retired from the army in 1951 and entered the world of business for several years.

His 1958 memoir Wedemeyer Reports! was a sharply revisionist critique of U.S. policy and policymaking in World War II. Published at the height of the Cold War, it remained on the best-seller lists for many months and brought its author much public acclaim and criticism.

Retiring to his Maryland farm, Wedemeyer continued to sustain a passionate interest in public affairs and to preach the need for more systematic and forward-looking national policies. The agonies of Vietnam—and the tragic failure of vision those agonies implied—reinforced these views. The old strategist was especially troubled by what he perceived as a pattern of reactive U.S. foreign policies that routinely yielded the initiative in the Cold War to the nation’s adversaries.

Throughout the long decades of the Cold War, Wedemeyer was viewed in liberal circles as a dangerously uncompromising hawk, but his insistence on more forceful and proactive policymaking was rooted less in aggressive nationalism than in profoundly humanitarian and idealistic impulses. He earnestly hoped that the terrible costs of war could be alleviated, that what he called the "inane cycle" of destroying and then rebuilding the world could somehow be broken.

In the closing decades of his long life, Wedemeyer also played the role of culture critic, hitting the lecture circuit frequently to defend the basic institutions of home, church, and school and to lend his support to conservative causes such as limited government, ordered individual freedom, and private enterprise.

Wedemeyer was promoted to four-star rank on the retired list in 1954. In addition to his many military awards and decorations, in 1985 he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Reagan, who had these words to say:

As one of America’s most distinguished soldiers and patriots, Albert C. Wedemeyer has earned the gratitude of his country and the admiration of his countrymen. In the face of crisis and controversy, his integrity and his opposition to totalitarianism remained unshakable. For his resolute defense of liberty and his abiding sense of personal honor, [he] has earned the thanks and the deep affection of all who struggle for the cause of human freedom.

Wedemeyer died on December 17, 1989, and his ashes were interred in Arlington National Cemetery. Much of the paper trail left by this uncommon American in the course of his several careers has been gathered and preserved by the Hoover Institution Archives, where it is open to researchers seeking to understand the endlessly challenging and elusive phenomena of war, revolution, and peace.