- Military

- Contemporary

- Security & Defense

- Terrorism

- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

- History

Memorial Day, the holiday that for many people means only the start of summer, challenges Americans to remember not just the what of the past, but the why. How a nation reflects on war while preserving peace became a matter of vital importance after the Civil War, when the holiday was born, and remains just as crucial today, as the clashes that followed the 9/11 terrorist attacks begin to recede into the past.

Memorial Day points to the memory of our shared past, so one can’t talk about its purpose without reference to history. It began as Decoration Day—a day to lay flowers at the graves of the loyal dead. As time passed, and the nation strove for reconciliation of North and South, there were calls for discontinuing Decoration Day. Even a radical Republican like Charles Sumner proposed that Congress should ban the practice of displaying the names of Civil War battles on Union regimental flags—too triumphalist, he thought.

In 1884, barely two decades after the war, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. gave a Decoration Day address in which he offered his own way out of the dilemma of how to commemorate a civil war without needlessly refighting the war. Holmes says right from the start that the answer he is about to give to the question “Why Memorial Day?” is meant to satisfy both “we of the North and our brethren of the South.” It is emphatically not the answer that would come to mind to his immediate audience there in Keene, New Hampshire, or, as he puts it, “not the answer that you and I should give to each other.”

In other words, Holmes deliberately sets aside questions about justice, about who started the war and for what each side fought. He abstracts from the larger purposes and meaning of the Civil War. Accordingly, there is only the briefest mention of slavery, near the beginning, where he indicates his own conviction, and the conviction of many in the North, “that slavery had lasted long enough.” But he makes barely a mention of union, liberty, or patriotism, and nowhere does he use the words rebellion, secession, or treason.

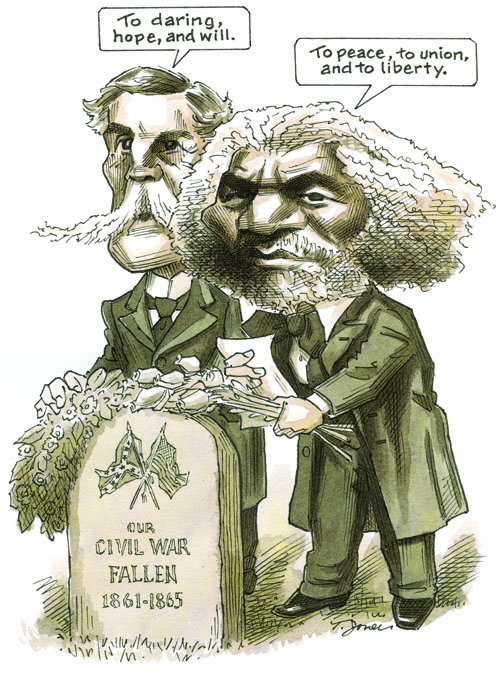

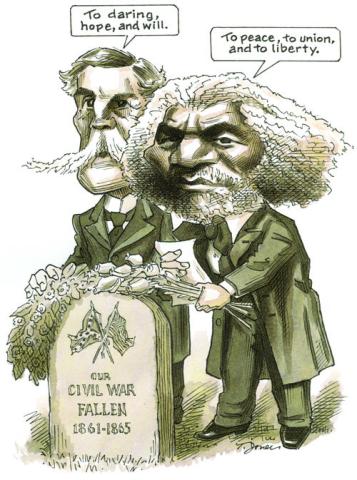

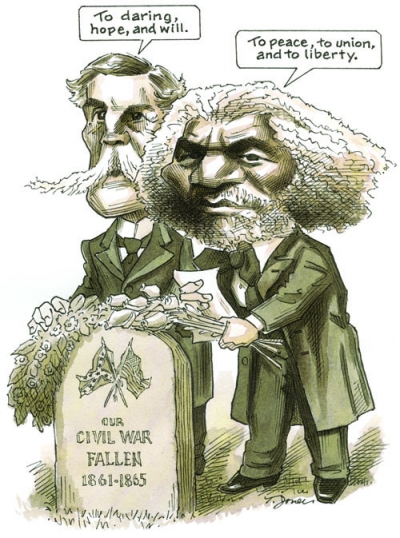

Holmes makes the best case he can for the moral equivalence of North and South. He states that Confederate convictions were just as “sacred” to those who held them and further that respect is due to those “who give all for their belief.” Both sides sincerely believed there was something worth fighting and dying for; we should celebrate the fact of “enthusiasm” and not inquire too closely into what those respective somethings were. Having stripped away judgments of principle, what remains is the poetic exaltation of “daring, hope, and will”—“will” appropriately enough is the very last word of his speech.

The poetry of the speech is seductive. Holmes offers a gorgeous portrayal of courage. His evocation of what he calls “the type” of the soldier is incredibly moving: “Unmarshalled save by their own deeds, the armies of the dead sweep before us, ‘wearing their wounds like stars.’ ” Very poignantly, he acknowledges the sufferings and sacrifices of women: “those lovely, lonely women, around whom the wand of sorrow has traced its excluding circle—set apart, even when surrounded by loving friends.” For the living, Holmes derives a message that seeks to transcend grief and points toward a reawakened commitment to life. It is important that Memorial Day is set “in the full tide of spring.” It represents a pause but not a stop.

Despite the undeniable beauties of this speech, it seems to me that Holmes pays too high a price for this attempt at national reconciliation. Courage is a virtue; indeed, it is a necessary virtue for the maintenance of every political order. And yet that is precisely the problem: courage, more than any other virtue, can be morally ambiguous. The Confederates were indeed courageous. So too, not to put too fine a point on it, were the Nazis. There have always been political orders that make manly virtue the be-all and end-all of life, such as the Spartans or the Romans.

But the United States, as a nation founded on a self-evident truth—the equality of all men—cannot have a national holiday that celebrates only courage. American courage ought always to be set in the context of another virtue, justice. In a sense, subsequent wars—all foreign wars—solved the Decoration Day dilemma, since we could honor more-recent veterans without confronting the contrast between the loyal blue and the rebel grey.

One assumes that even Holmes would not have extended his cultural relativism so far as to collapse the moral distinction between the Allied and Axis powers or between the Americans and the North Koreans, or North Vietnamese, or Islamist terrorists—although, of course, there have been elite opinion-makers who do go that far. Unfortunately, however, there is nothing in Holmes’s speech that would offer a bulwark against such a relativist assault on American patriotism and American exceptionalism. Accordingly, we should look elsewhere for an answer to the question “Why Memorial Day?”

NO HOLIDAY FROM SELF-CRITICISM

Just two years before the speech by Holmes, in 1882, there was another Memorial Day address, this one by Frederick Douglass, which bore the title “We Must Not Abandon the Observance of Decoration Day.” Douglass, the former slave who turned abolitionist and then Republican officeholder, gives a very different answer to the question “Why Memorial Day?” Like Holmes, he looks toward national reconciliation, but he does so on the firm ground of principle. Addressing himself to “loyal and patriotic men, in every part of our common country,” he honors those who “gave their lives . . . to save their country from dismemberment and ruin.”

A decade earlier, Douglass had already noted and resisted the growing tendency to gloss over the difference between the North and the South. In another Decoration Day address, this one delivered in 1871 at Arlington National Cemetery, he had said: “We are sometimes asked, in the name of patriotism, to forget the merits of this fearful struggle, and to remember with equal admiration those who struck at the nation’s life and those who struck to save it, those who fought for slavery and those who fought for liberty and justice.” Douglass fully admits that “unflinching courage marked the rebel not less than the loyal soldier,” but he insists that “we are not here to applaud manly courage, save as it has been displayed in a noble cause.”

Douglass feared that reconciliation between North and South would be based on forgetfulness or nostalgia rather than “the new birth of freedom” set forth by Abraham Lincoln. Rejecting the distortions of nostalgia, Douglass sides with a fuller form of remembrance—we need to remember, he says, “the causes, the incidents, and the results of the late rebellion.”

Whereas Holmes waxes poetic about the beauty of the war—“in our youth our hearts were touched with fire”—Douglass exposes precisely what it was that “fired the Southern heart”: namely, “the dark and vengeful spirit of slavery.” He lays stress not on the enthusiasm and passion experienced in battle but rather on the terrible ugliness of war—a war “which has made stumps of men of the very flower of our youth; which has sent them on the journey of life armless, legless, maimed, and mutilated” and “swept uncounted thousands of men into bloody graves and planted agony at a million hearthstones.” But above all else, Douglass insists on the redemptive result of the war: the victory of Union arms, blood-bought though it was, meant “a united country . . . [where] the star-spangled banner floats only over free American citizens in every quarter of the land.”

Douglass calls for honest remembrance not just out of fidelity to the past but for the sake of the future. He enjoins the “thoughtful statesman” to study the conflict, for it is, he says, “full of lessons of wisdom, courage, and patriotism.” Courage, yes, but flanked by and enfolded within other virtues, on one side the higher virtues of thought and intellect, on the other love of country. For Douglass, the graveside rituals and ceremonies of Decoration Day become in effect “an altar . . . around which the nation can meet one day in each year to renew its national vows and manifest its loyal devotion to the principles of our free government.”

Douglass believes that this vantage point—from which one can survey past, present, and future—ought to prompt reflection on “themes of immediate national interests.” And thus, near the close of the 1882 address, Douglass assesses the situation facing three particular groups: the freedmen, the Chinese, and the Hebrews—warning Americans against “persecuting any variety of the human family.” For Douglass, the Decoration Day holiday is not a holiday from the rigorous self-criticism demanded by self-government.

Holmes closes his address with a paean to “daring, hope, and will.” Douglass closes his with a strikingly different trifecta. He speaks of service “to peace, to union, and to liberty.” Holmes speaks of means or instrumentalities, Douglass of ends or purposes. For Douglass, daring, like war itself, must be in the service of peace. Hope must be for union, not disunion. And the will must direct itself to what is truly will-worthy: liberty, not despotism.

WHAT MAKES A MEMORY HONORABLE?

I would like to end with my own suggestion for renewal. Two restorations would, I believe, reinforce the real import of the holiday. We should start by reviving the original name, Decoration Day. Decoration Day is better than Memorial Day since it indicates the action required of citizens: to decorate the graves of those who have fallen in service to their country. At the same time, we should restore the holiday to its long-standing date of May 30. Decoupling the holiday from the three-day weekend where it has been ensconced since 1971 would increase the likelihood that citizens would carry out their graveside duties, instead of planning mini-vacations and shopping trips.

Finally, we should continue to stress, as Douglass did, what makes these deaths honorable. Decoration Day renews the memory of the men and women who have given their lives in the defense of free government against both internal and external threats. That remembrance should strengthen us in our devotion to the always “unfinished work” of ensuring that our nation and our form of government “shall not perish from the earth,” to quote Lincoln, who delivered the first and greatest American memorial address at Gettysburg.