- Budget & Spending

- Economics

- Law & Policy

- Regulation & Property Rights

- Campaigns & Elections

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- Congress

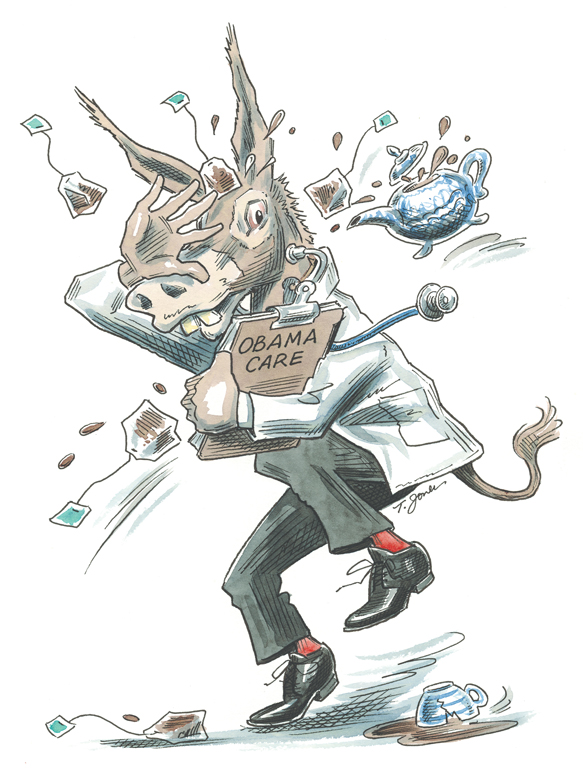

- Health Care

The majority party normally loses seats in midterm elections, but the Republican resurgence of recent months suggested more than a conventional midterm rebound. How did an obscure Republican run a competitive Senate campaign in Massachusetts and win? The answer was voter leeriness about health care reform, and Scott Brown’s surprising capture of the late Edward Kennedy’s seat suggested that Democrats will face even worse problems later this year in places less liberal than Massachusetts.

We polled voters in eleven states likely to have competitive Senate races in November on how they felt about health reform and how they might vote in November. The interviews were conducted January 6–11 with 500 registered voters in Arkansas, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Louisiana, Missouri, Nevada, North Dakota, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. The polls were conducted by YouGov using a selected panel of Internet users representative of the registered voters in each state.

Earlier this year, support for health care reform varied in these eleven states from a low of 33 percent in North Dakota to a high of 48 percent in Nevada. Democrats trail Republicans in six of the states; three are toss-ups; and in two, Democrats have a solid lead.

Support for the Republican Senate candidates in these races was closely related to voter opposition to the Senate health care bill. In North Dakota and Louisiana, opponents of the bill outnumbered supporters by around 30 percent. In North Dakota, Democratic incumbent Byron Dorgan withdrew from a difficult race, which it now appears will be won handily by Republican Governor John Hoeven (who in our hypothetical matchup led 58–30 percent against Heidi Heitkamp, a former attorney general of the state, and 56–29 percent against Representative Earl Pomeroy. Both Heitkamp and Pomeroy have since withdrawn from the Senate race). In Louisiana, Republican incumbent David Vitter, who was thought to be vulnerable, was leading Representative Charlie Melancon by 20 points. In Delaware, 49 percent supported the bill, and Republican Representative Mike Castle was leading Beau Biden, the state’s attorney general and the son of the vice president, 49–37 percent (Biden, too, has now withdrawn).

In Nevada, the bill was relatively popular (although in none of the states did it receive majority support). Nonetheless, incumbent Harry Reid was in a toss-up against either Sue Lowden (a former state senator and news anchorwoman) or Danny Tarkanian (a real estate investor). In Connecticut, 44 percent of voters supported the Senate bill, and Connecticut Attorney General Richard Blumenthal led 47–35 percent against Republican Linda McMahon, former CEO of World Wrestling Entertainment, and 47–34 percent against Republican former congressman Rob Simmons. In Pennsylvania and Colorado, 43 percent of voters supported the Senate bill, and Democrats trailed Republicans by 2.5 and 4.5 points, respectively.

How do we know that the health reform bill was to blame for the low poll numbers for Democratic Senate candidates, rather than that these are just more conservative states?

First, we asked voters how their incumbent senator voted on the health care bill that passed on Christmas Eve. About two-thirds answered correctly. Even now, long before Senate campaigns have intensified, voters know where the candidates stood on health care. Second, we asked voters about their preference for Democratic versus Republican candidates in a generic House race. As in the Senate, the higher the level of opposition to health reform, the greater the likelihood that the state’s voters supported Republicans.

Several months must pass until the midterm elections. It is hard to predict the influence of an issue, even one as important as health care, so far in advance. But it is clear that when incumbent Senate and House Democrats return home to campaign this fall, they will be explaining why they voted for a bill that so many of their constituents opposed.