- Economics

- Contemporary

- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- History

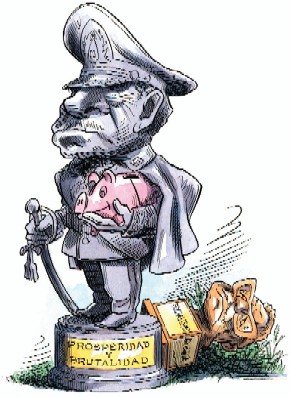

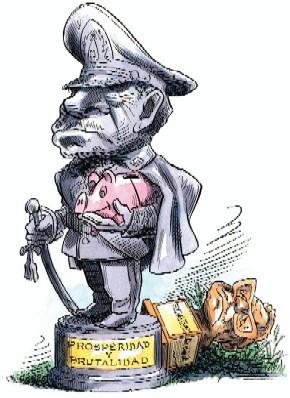

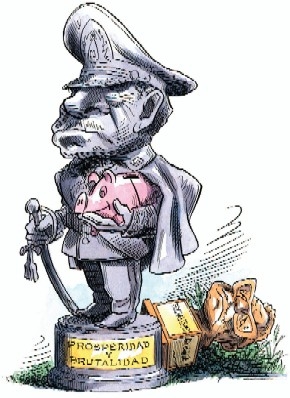

Chile’s former president, General Augusto Pinochet, died in December. Some of his legacies are well known, but others are not.

Pinochet directed the coup of September 11, 1973, and presided until 1990 over a military regime that violated human rights, shut down political parties, canceled elections, constrained the press and trade unions, and engaged in other undemocratic actions during its more than 16 years of rule. These facts are important and widely recounted.

A number of other important truths about the Pinochet period and its legacy are equally well documented but less well known. Indeed, they are often not acknowledged at all. (A notable partial exception to this rule was the Washington Post editorial of December 12 that bore the headline “A dictator’s double standard: Augusto Pinochet tortured and murdered. His legacy is Latin America’s most successful country.”) We will focus on the generally neglected, discounted, distorted, and sometimes falsely denied or suppressed aspects of the Pinochet legacy that have truly made Chile, despite its continuing challenges, “Latin America’s most successful country.”

What Kind of Democracy Did the Coup Displace?

The 1973 coup is often represented as having destroyed Chilean democracy. Such characterizations are half-truths at best. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Chile’s democracy was already well on the road to self-destruction. The historian James Whelan caught its tragic essence when he wrote that Chile’s was a “cannibalistic democracy, consuming itself.” Eduardo Frei Montalva, Chile’s president from 1964 to 1970, who helped to bring in Salvador Allende as his successor, later called the latter’s presidency “this carnival of madness.” Freedoms increasingly overwhelmed responsibilities. Lawlessness became rampant. Uncontrolled leftist violence had also been escalating during the government of Christian Democrat Frei Montalva, before Allende became president and long before Pinochet played any role whatsoever in Chilean politics.

In 1970, Allende won 36.2 percent of the popular vote, less than the 38.6 percent he had taken in 1964 and only 1.3 percent more than the runner-up. According to the constitution, the legislature could have given the presidency to either of the top two candidates. It chose Allende only after he pledged explicitly to abide by the constitution. “A few months later,” Whelan reports, “Allende told fellow leftist Regis Debray that he never actually intended to abide by those commitments but signed just to finally become president.” In legislative and other elections over the next three years, Allende and his Popular Unity (UP) coalition, dominated by the Communist and Socialist parties, never won a majority, much less a mandate, in any election. Still Allende tried to “transition” (his term) Chile into a Marxist-Leninist economic, social, and political system.

Allende’s closest UP allies were the Communists, the right wing of the UP, but both were pressed to move faster than they wanted by the left wing of the UP, mainly members of Allende’s Socialist Party, and by ultraleftists (the term used by the Communists) to the left of the UP. Violence escalated rapidly, with the extreme left, including many members of the president’s own party, seizing properties and setting up independent zones in cities and the countryside, often contrary to what Allende and the Communists thought prudent. In the process Allende, his supporters, and extremists they could not control virtually destroyed the economy, fractured the society, politicized the military and the educational systems, and rode roughshod over Chilean constitutional, legal, political, and cultural traditions. Thus by July 1973, if not earlier, Chile was looking at an incipient civil war.

| Pinochet’s 1973 coup was supported by Allende’s presidential predecessor and by an overwhelming majority of the Chilean people. |

Many on the left had long believed that capitalism and democracy were incompatible. In a brazen demonstration of its contempt for majority wishes, and for the institutions of what it called “bourgeois democracy,” the pro-Allende newspaper Puro Chile reported the results of the March 1973 legislative elections with this headline: “The People, 43%. The Mummies, 55%.” This attitude and the actions that followed from it galvanized the center-left and right, whose candidates had received almost two-thirds of the votes in the 1970 election, against Allende. On August 22, 1973, the Chamber of Deputies, whose members had been elected just five months earlier, voted 81–47 that Allende’s regime had systematically “destroyed essential elements of institutionality and of the state of law.” (The Supreme Court had earlier condemned the Allende government’s repeated violations of court orders and judicial procedures.) Less than three weeks later, the military, led by newly appointed army commander in chief Pinochet, overthrew the government. The coup was supported by Allende’s presidential predecessor, Eduardo Frei Montalva; by Patricio Aylwin, the first democratically elected president after democracy was restored in 1990; and by an overwhelming majority of the Chilean people. Cuba and the United States were actively involved on opposite sides, but the main players were always Chilean.

Authoritarian, Not Totalitarian

The Chilean military regime from 1973 to 1990 was authoritarian, certainly, but not totalitarian. This distinction is fundamental in comparative political analysis. Totalitarian regimes legitimize and practice very high degrees of penetration into all aspects of the economy, society, religion, culture, and family, whereas authoritarian regimes do not. Totalitarian regimes have dominant single parties; coherent, highly articulated, widely disseminated ideologies; very high levels of mass mobilization and participation directed and manipulated by the regime; and a strict control over candidates, when there are any, and policies. Authoritarian regimes have mentalities more than ideologies, low levels of political participation, and limited pluralism and competition of policies and political actors (including the press), with some constraints on regime control and manipulation of the polity, society, economy, family, religion, culture, and the press.

Consider also the two types of regimes’ different propensities to enable a transition to democracy. Totalitarian systems—once in place and short of external military conquest and occupation—are much harder to change than authoritarian ones. Pinochet’s authoritarianism in Chile ended after 16 years in a peaceful and constitutional transfer of power, permitted by a constitution passed in 1980; Castro’s totalitarian regime in Cuba has lasted 48 years so far. Chile’s democracy after 1990 has been vigorous and stable. As reported by Hector Schamis in the Journal of Democracy (October 2006), Chile’s current foreign minister, Alejandro Foxley, recognized early in the first post-Pinochet democratic government that “the constitutional rules left by Pinochet had ‘somewhat ironically fostered a more democratic system,’ for they forced major actors into compromise rather than confrontation and, by ‘avoiding populism,’ increased ‘economic governability.’”

The Economic Legacy

It has become fashionable in some quarters lately to claim that Chile’s successful record of economic development in recent decades actually began in 1990, during the first civilian government since 1973. That claim is false. The historical record is clear. President Pinochet and his civilian advisers, after an elaborate and lengthy process of deliberation and decision making in 1973–1975, in which various alternative courses of action were considered, put in place the radically new set of market-oriented structures and policies that have been and remain the foundations of Chile’s subsequent three decades of economic and social development. This new model, which we call social capitalism, was adjusted, revised, and supplemented during the Pinochet years, most importantly in response to an economic crisis in the early 1980s and also in the post-1990 civilian years. But its main elements have not changed, and thus far no post-1990 government has proposed or seriously considered going back to either of the two previous, failed models, namely, state capitalism (1938–70) or state socialism (1970–73).

As the then finance minister, Alejandro Foxley, said in a 1991 interview: “We may not like the government that came before us. But they did many things right. We have inherited an economy that is an asset.” All four civilian governments since 1990 have maintained the new, more market-oriented economic and social models inherited from the military regime. Although there were changes at the margins after 1990, the point of sharpest and deepest positive change was unquestionably 1973 and immediately thereafter, not 1970 or 1990.

The Neoliberalism Myth

It is often said and widely believed that Pinochet’s economic reforms eliminated any significant role of the state in the economy. The claim is that he introduced a neoliberal model, that is, raw, savage capitalism of the kind attributed to Chile in the nineteenth century. The facts are otherwise. Chile’s largest industry and biggest foreign-exchange earner by far is copper, which was nationalized in the late 1960s and early 1970s and has remained so ever since. Domestic banks were deregulated in the late 1970s but reregulated with vigor in the early 1980s. Poverty had increased enormously during and in the wake of the UP’s disastrous economic policies, and it decreased only as a result of the state-led stabilization policies, structural reforms, and targeted social programs of the Pinochet period. Major state expenditures for direct action social programs targeted to the poorest of the poor were initiated in the middle 1980s, not after 1990. Poverty levels, as high as 50 percent in 1984, were reduced to 34 percent by 1989. They continued to fall after 1990 to 15 percent in 2005. The Concertación, the alliance of political parties of the center and left that has won the past four presidential elections, deserves some credit for the post-1990 years, but so does the Pinochet government. It created the underlying economic policies and structures in the 1970s and 1980s that the Concertación maintained and that produced jobs for the poor and an economic surplus to enable targeted state antipoverty programs.

Legacies for the World

The innovations in economic and social policy of the Pinochet government had significant influences on, and implications for, not only subsequent governments in Chile but also the rest of Latin America and the wider world. Today almost the entire globe relies on the state less and on markets more than in 1973. The first country in the world to make that momentous break with the past—away from socialism and extreme state capitalism toward more market-oriented structures and policies—was not Deng Xiaoping’s China or Margaret Thatcher’s Britain in the late 1970s, Ronald Reagan’s United States in 1981, or any other country in Latin America or elsewhere. It was Pinochet’s Chile in 1975.

| What once looked like a reactionary economic model is now the standard in much of the world. |

At that time the Chilean economic model was considered anathema almost everywhere—partly because of its association with Chile’s military regime but also because it was viewed (wrongly, as it turned out) as an unthinkable, reactionary model per se, especially for developing countries. (Of the many military regimes in Latin America in the sixties, seventies, and eighties, the only one to break with state capitalism was Chile’s.) But global perceptions of the Chilean economic model changed, slowly at first, more rapidly and massively after the mid-1980s. By now, the economic policies of most countries of Latin America; North America; Western, Central, and Eastern Europe; China; India; Russia and its former republics; much of Africa; and many other places around the world have followed the Chilean lead rather than fled from it.

The autumn of Two Dictators

Pinochet’s death occurred just as Fidel Castro was lying gravely ill in Cuba. Have commentators described and evaluated them with equal accuracy and fairness over the decades?

Castro killed at least as many Cubans as Pinochet did Chileans. Pinochet’s government has been justly condemned for engaging in some terrorist activities abroad, from Argentina to the United States. Amnesty International strongly supported the Chilean leader’s extradition to Spain in 1998 for a trial it thought would enact justice. But Castro trained thousands of guerrillas from countries all over the world and sent hundreds of thousands of Cuban troops to many countries on at least three continents to launch and wage wars that brought untold death and destruction. We can’t recall human rights organizations agitating for his extradition, or for his being brought to justice even posthumously in Cuba. Finally, Chile is the most successful case of economic, social, and political development in Latin America and a pioneer in the global shift to enlightened social capitalism. Cuba is a dismal, impoverished, dynastic totalitarian anachronism.

| All four civilian governments since 1990 have maintained the new, more market-oriented economic and social models inherited from the military regime. |

How many nations a decade or century from now will aspire to the “successes” of Fidel Castro—or of Salvador Allende? A much more positive case can be made for major parts of Pinochet’s legacy. It’s time to acknowledge that the legacies of the Pinochet years are a much better mix than they are usually said to be.