- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- The Presidency

One way to understand the ebb and flow of politics in Sacramento is by dividing the year into quarters.

The first quarter: California’s governor unveils a budget proposal early in January (with the budget in place at the time set to expire at the end of June), followed by an expressed set of priorities via the annual State of the State Address—netting as a result something of a sitzkrieg as the state legislature ponders the two products.

The second quarter: the legislature and the governor find common ground—in surplus years, as seems likely in 2022, quite literally spreading the wealth—and put the new spending blueprint in place before July 1 at the beginning of the new state fiscal year (it’s been more than a decade since California began its new fiscal year without a budget in place).

The third quarter: the legislature turns its focus to the legislative slate—this year, a September 10 deadline to forward measures to the governor for his consideration.

And the present fourth quarter: the governor has a month to weigh in on said bills (if a California governor chooses not to act on a bill that clears the legislature, it automatically becomes state law).

Why the need to explain this? Because as much as we look to the winter’s big gubernatorial address and the summer’s big budget as microcosms of California’s progressive predilections, the fall’s month-long bill-signing season likewise is a window into the state’s political soul.

So what have we learned so far?

In a nutshell: woke isn’t broke.

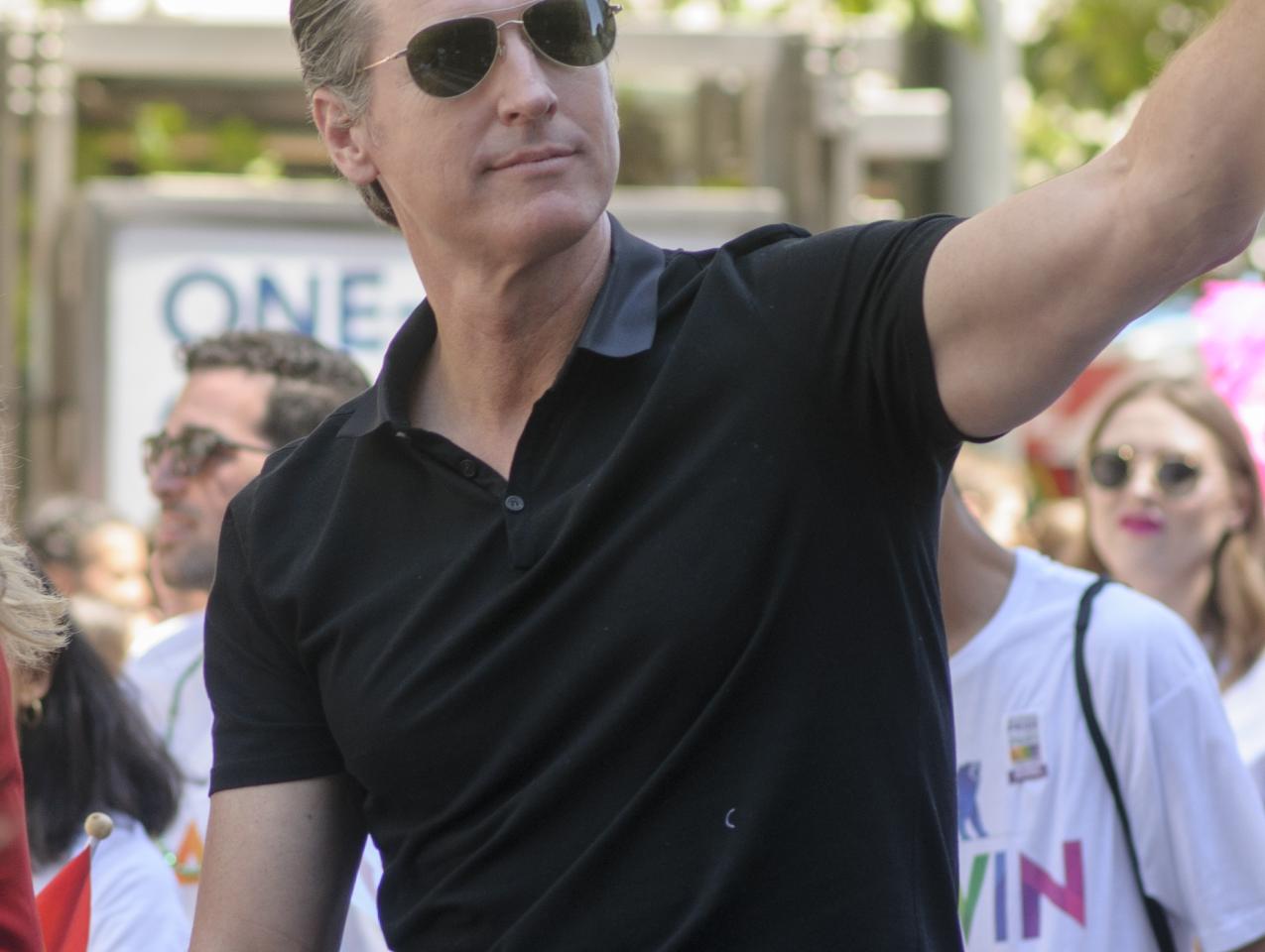

And, if you thought California governor Gavin Newsom was a changed man having survived last month’s recall election . . . guess again.

Case in point: policing.

Last week, Newsom ventured to the Southern California town of Gardena (it’s roughly midway between Los Angeles and Long Beach) to sign a series of bills altering how law enforcement is practiced in the Golden State).

Among the changes: new rules for officers to intervene when a fellow officer is perceived to be using excessive force (a so-called George Floyd Law) and allowing officers’ badges to be permanently taken away for excessive force, dishonesty—and racial bias.

Never mind that the venue Newsom chose for the ceremony offers a complicated tale about law and order. It was held at a park where a young Black man was shot to death by a police officer three years ago. However, the officer involved in the shooting was subsequently cleared of wrongdoing (a Los Angeles DA report saying he acted in self-defense).

That wasn’t the same image Newsom presented as recently as a few weeks ago, when his political future was on the line. During the recall election, Newsom offered a tough-on-crime persona, targeting retail theft and organized theft rings as a concern for his administration (maybe you’ve seen the footage of this brazen theft at a San Francisco Walgreens). Post-recall, the focus would seem to be on pursuing law officers more so than lawbreakers.

Second case in point: Newsom again into delving into racial justice, this time at a ceremony in Manhattan Beach during which he signed a bill returning two oceanfront lots to the descendants of the tract’s former Black owners.

The event tapped into California history—a Black couple purchasing the land over a century ago, at a time when Black Californians had limited beach options due to segregation laws, only to see it taken away due to eminent domain.

But for Newsom, it became an opportunity to connect California’s past to a present debate over racial reparations, currently the subject of one of the seemingly infinite number of task forces that the governor is fond of creating (in June, California became the first state in the nation to weigh reparations—a two-year process to study both slavery and systemic racism in the Golden State).

A third case in point, though this isn’t a bill but instead an executive order: Newsom last week making California the nation’s first state to require COVID-19 vaccinations for in-person school attendance (pending FDA approval for the K–6 and 7–12 age groups).

Why this fits in with the two aforementioned bill signings: it’s an action Newsom didn’t take during the height of the recall election (the date of that vote—September 14—coming more than three weeks after California schools began the academic new year). And it points to a dichotomy: Newsom only encouraged California teachers and school staff to get jabbed, no mandate there; and the governor chose not to make COVID-19 vaccinations mandatory for California prison guards, whose union donated generously to Newsom’s anti-recall committee.

So where does California go from here?

By the time you read this, bill-signing season may be over in Sacramento.

But not the woke symbolism in which Gavin Newsom likes to bask.

As such, it constitutes California coming full circle since Newsom first took office in 2019. That freshman year featured Newsom reveling in all sorts of matters that didn’t see the light of day during the less-progressive days of his predecessor, Jerry Brown—for instance, requiring college health clinics to provide abortion pills, along with UC and CSU requirements to offer students medical abortions.

Newsom’s second legislative year was redefined by the pandemic, with the governor signing such matters as sparing renters from eviction and expanding paid family leave.

And now, in year three of bill signing, Newsom re-emerges as an avatar for causes near and dear to the progressive cause (those would include race, victimization, and complicating life for law enforcement).

There may be a surprise here or there before the fourth quarter ends. This year, for example, Newsom did veto a bill enabling farm workers to vote by mail in union elections. That prompted the United Farm Workers, which supported Newsom in the recall, to organize a march to both the French Laundry restaurant (scene of the infamous Newsom dinner party that jump-started the recall) and a winery owned by the company Newsom founded.

Though an outspoken gun-control advocate, Newsom likewise vetoed a bill requiring California’s Justice Department to verify hunting licenses before approving firearm sales to individuals under 21 (Newsom claimed the technology needed would have disrupted the department’s other efforts to do background checks).

Otherwise, look for a humility stress test in Sacramento as the calendar turns to a new year: a governor glowing in the aftermath of crushing his recall opposition, with billions in revenue to spend, more than willing to offer himself as an avatar for a national political party in search of a figure who can pair woke rhetoric with woke results thanks to his (and Democrats’) domination of California’s political landscape.

Consider this your woke-up call for 2022.