In the past twelve years, 800 American women have been wounded and 136 killed in our wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Nearly three hundred thousand have deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. Yet women remain barred from service in infantry, artillery, armor, combat engineers, and special operations units.

Mythology. There are three prevalent myths about the United States military’s combat exclusion policy. The first myth is that women are prevented from serving in combat. Women are serving in combat; they are prevented from being assigned to units whose primary mission is ground combat. The second myth is that they are excluded by law. There is no legal exclusion of women from assignment to combat units; they are excluded as a matter of Department of Defense policy, and that policy varies by Service. The third myth is that manpower needs constitute a strong argument for opening combat units to women. In nearly every case of countries that permit it, including Israel, women constitute about 2% of combat forces.

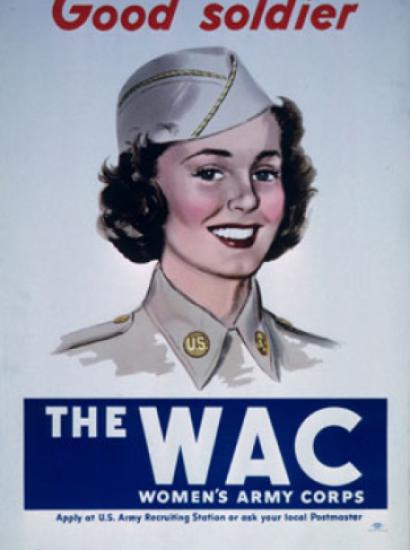

History. The 1948 Women’s Armed Service Integration Act established permanent female service in the American Military. It also limited the proportions of women who could serve and hold officer’s ranks, and prohibited assignment to aircraft or ships considered combatants. Restrictions on the numbers of women who could serve were removed in 1967, but they resulted in no greater numbers of women joining the force.

A substantial increase of women in the American military occurred with the advent of the All-Volunteer Force in 1973. In 1988, the Pentagon established the “risk rule,” which determined that women could be excluded from military occupational specialties with “exposure to direct combat, hostile fire, or capture.” The rule was rescinded in 1994 on the argument that all U.S. forces in the theater of war were subject to those risks. Servicewomen could then be excluded only from “assignment to units below the brigade level whose primary mission is to engage in combat on the ground.”

Current Practice. Nearly all occupational fields are open to women in the Air Force and Navy (women currently serve even aboard submarines). Women are currently excluded from infantry, artillery, armor, combat engineers, and special operations units of battalion size or smaller. The question of combat exclusion is thus principally an Army and Marine Corps issue, and principally about whether to force integration of ground combat units.

A subtle but important distinction exists between assignment and employment policy. That is, current policy prevents assigning women to ground combat units, but it does not proscribe the activities they can perform. The local commander has authority to use all available personnel to fulfill the unit’s mission, and therefore to order female soldiers into combat roles.

Existing policy also does not prohibit the “attachment” (as opposed to assignment) of women to combat units. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have, in fact, seen female service members attached to combat units is significant numbers. Women have served in Army forward support companies attached at the brigade level but operating as part of battalions, and in explosive ordinance disposal teams of all Services.

The success of female engagement teams–soldiers and Marines assigned to all-female units but attached to male combat teams to perform searches and interrogations–has further blurred the line because those women have been exposed to hostile fire, direct combat, and capture. That they have performed well and met an acknowledged operational need (traditional societies’ aversion to male contact with women) reduced resistance to their inclusion, even among infantry and special operations units.

The Obama Administration announced in January its intention to “eliminate all unnecessary gender-based barriers to service.” The military Services were instructed to develop plans for full integration of women into all military occupational specialties by January 2016, justifying any “necessary” gender-based barriers.

Changing Current Policy. Allowing assignment of women into ground combat units carries a number of policy concerns, including whether women are strong enough, physically and emotionally, for combat; whether the presence of women negatively affects unit cohesion; the problems that arise from involuntary assignment; and the effect forcing the policy change may have on civil-military relations.

The majority of men in both the Army and Marine Corps support continuation of the combat exclusion for women. Surveyed last year, 17% of men in the Marine Corps responded that they would leave the Service if women were permitted in combat units.

Across the Services, a high proportion of women among junior enlisted and junior non-commissioned officer ranks support lifting the combat exclusion. However, senior female non-commissioned officers and female officers are much less supportive of changing the policy. Thirty-four percent of female Marines responded they would volunteer for ground combat units if given the chance; but 17% would leave the Marine Corps if they were at risk of being involuntarily assigned to a combat unit. Ninety percent of enlisted women in the Army responded they would leave service if they could be involuntarily assigned to combat units.

Mission effectiveness. Opposition to women being assigned to combat units comes primarily from those serving in them. While 74% of the general public would support changing the policy, the characteristic attitude among infantrymen on the subject is that “‘integration’ erodes combat effectiveness–lowering behavioral and proficiency expectations and riddling the force with time-consuming misconduct issues.” 1

Physical standards currently are gender specific in the military. The Army physical fitness test requires the same number of sit ups for men and women, but women are given more lenient standards for push ups and the timed run. The Marine Corps physical fitness test allows women to hang from a bar instead of doing pull ups. Where combat training has been opened to women (both in other countries, and in recent U.S. Marine Corps efforts), few women apply, and those that do suffer much higher injury and attrition rates.

Both the Army and, most aggressively, the Marine Corps are currently developing gender-neutral occupational standards for infantry. The Marine Corps flatly stated “the Marine Corps’ high standards cannot be lowered, nor can we artificially lower them to ensure a certain percentage of females will qualify.” Given the Marine Corps’ record of influence on Capitol Hill, they are likely to be given latitude to set their own standards.

However, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff has called such functional standards into question, suggesting he may intervene to reduce physical standards. General Martin Dempsey has said that “if we do decide that a particular standard is so high that a woman couldn’t make it, the burden is now on the service to come back and explain to the secretary: Why is it that high? Does it really have to be that high?”

Evidence is mixed on whether women experience greater trauma with combat exposure, in part because data have been only recently collected. Non-military health research suggests women may suffer post-traumatic stress disorders at higher rates then men, possibly because of gender differences in the processing of stress.

Unit Cohesion. The question is not just physical fitness, but also maintaining the operational integrity of the unit. Similes about chains being only as strong as their weakest link are frequent in military discussions of combat, with or without women. The men in infantry, artillery, armor, combat engineers, and special operations units strongly oppose any change in the exclusion. One possible explanation is that they are overwhelmingly misogynistic; another is that perhaps they know something about their profession the rest of us do not. The policy question them becomes whether to impose on those men the standards we hold in the broader society.

Many men in ground combat units express concern about deference to women changing the dynamic in their units: men protectively looking out for women to a greater extent than they do for men, giving women less dangerous jobs, or distracting attention in combat to care for women. This sometimes conflates with concerns about female physical and emotional fitness, but what the men are reporting is their concern about the behavior of other men with women in the unit. What little data there is on the subject do suggest units that have experienced female casualties have a more difficult time recovering.

And then there is sex. Not just sex between consenting adults, which by itself is often problematic within units, but sexual harassment, sexual assault, and the suite of related issues. Military commanders seek to limit these difficulties where possible because of their corrosive effect on unit morale and cohesion, and one way of limiting the problems is limiting contact. Men engaged in direct ground combat live in an environment of aggression, and tempering that aggression is difficult for leaders, whether the issue is restraint under fire or bringing civilian codes of conduct into combat environments.

These are difficult issue to discuss, given the political correctness surrounding them generally and the current furor about whether there is an epidemic of sexual misconduct in the military. But it is historically true that there is a connection between sexual scandals and policy changes advancing women’s opportunities in the military: the 1994 policy change resulted from the Tailhook scandal, not manpower needs or changes in the nature of the battlefield or how we fight.

Fairness Issues. American men are required to register for selective service when they turn 18, a practice the Supreme Court has upheld on the basis of the nation’s need for their combat service. Men do not always get to choose their branch of Service; assigning women to combat units will raise the issue of whether they can be assigned involuntarily to combat service. If so, it could lead to fewer women in service–negating the intentions of the policy. If not, it could constitute a gender bias against men. In either case, it will embroil the military in a host of practical implementation issues that most in the leadership would prefer not to have to deal with.

Civil-Military Relations. Major changes in military personnel exclusions–ending racial segregation in 1948, including women in 1973–tend to gain support of the military Services when manpower needs drive the policy change. With the end of wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the Army is currently scheduled to be reduced by 80,000 soldiers and the Marine Corps by 20,000; this is an unpropitious scenario for a policy change over the objections of the military leadership. Allowing the issue to advance because of concern about unwanted sexual contact among service members would create even more resentment.

And while the American military is comfortably subordinate to civilian control, thirty years of being a volunteer force in which only a small part of the general public bears the distinction and burdens of military service, and twelve years of being a military at war–not a country at war–has frayed somewhat the connection between our military and broader society. There is a strong sense among the military of being cursorily thanked for their service but society making no effort to understand their experience or weave veterans back into our communities. The separation of our military from the rest of society isn’t a danger to civilian control of the military, but it is deeply frustrating for many in the military that the rest of society freely imposes social diktats without trying to understand why the military has in place the standards and policies it does.

1 1st Lt Robert K. Wallace, “Women In Combat: The Issue Hasn’t Been Settled” (Marine Corps Gazette), http://www.mca-marines.org/gazette/article/women-combat-issue-hasnt-been-settled.