- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- Campaigns & Elections

- State & Local

- California

To the notion that things can change in a hurry, consider what defined California hardship a year ago at this time.

In the first week of August 2019, no fewer than 13 wildfires broke out—from as far south as San Diego to as far north as lightly populated Lassen County.

But that was relatively small potatoes compared to the previous year’s misery. In the summer of 2018, the largest blaze in California’s recorded history—the Mendocino Complex fire, which took over a month to contain—tore through Lake County (it’s north of the San Francisco Bay Area). Meanwhile, another terrible blaze, the so-called Holy Fire, zeroed in on the community of Lake Elsinore (it’s in western Riverside County), while way to the north the good citizens of Redding sifted through what remained after a 143-mph “fire tornado” took away their treasures.

As it’s now the eighth month of the calendar year, California once again finds itself in fire season thanks to a witch’s brew of dry conditions and lightning strikes. A week ago, the Caldwell Fire—it’s been raging in Modoc National Forest—became the largest fire in the state since 2018.

And last weekend, triple-digit weather in Southern California kept responders busy trying to prevent small brush fires from morphing into larger conflagrations.

But what’s different about this year’s fire season: it doesn’t drive the local news, as it usually does due to the trifold camera appeal of deadly flames, first responders on land and in air, and the tragedy of lives disrupted if not ruined. As long as the pandemic and its associated miseries—disease, death, economic impoverishment and social upheaval/inconvenience—continue to hold our attention, it may stay this way.

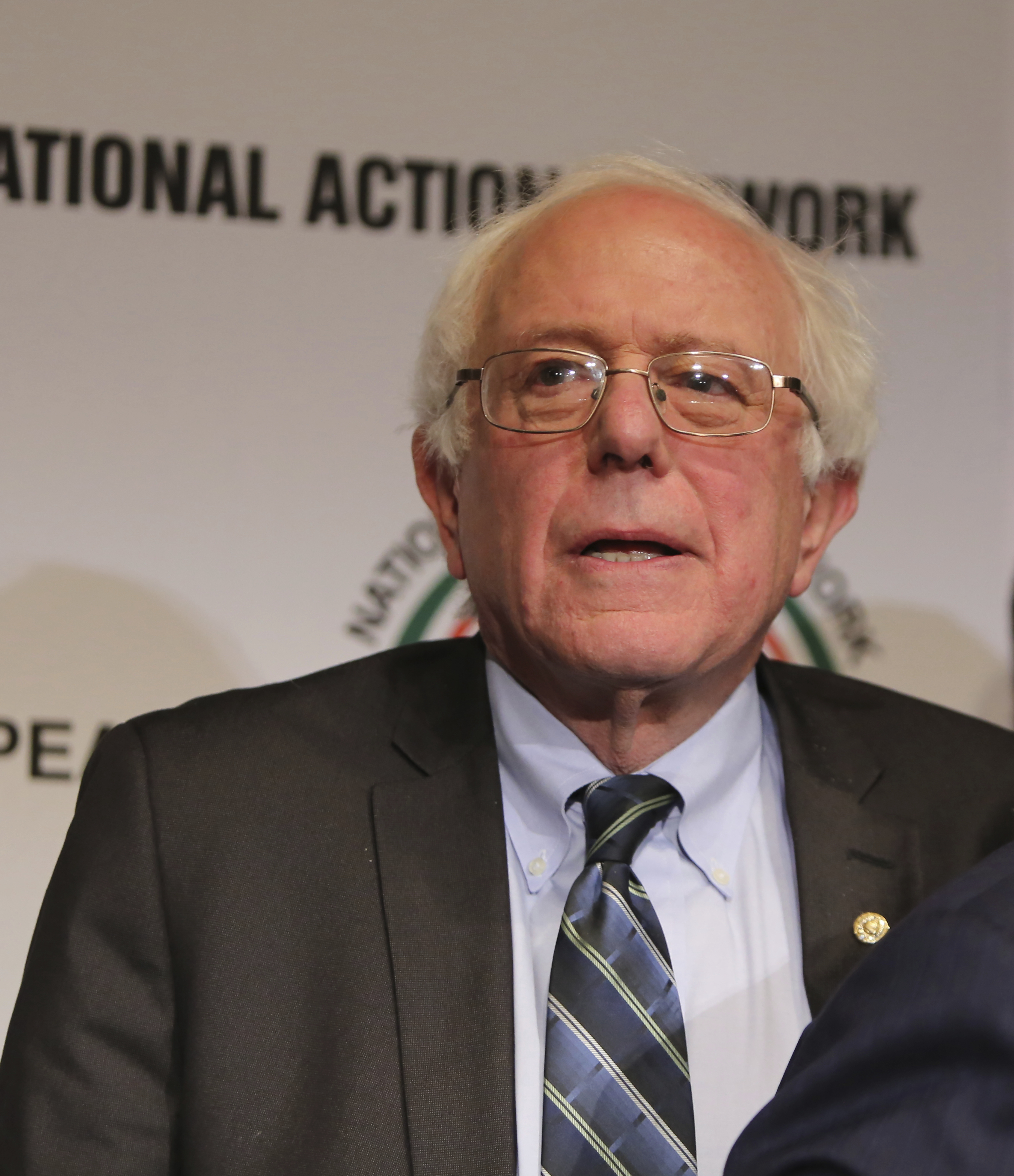

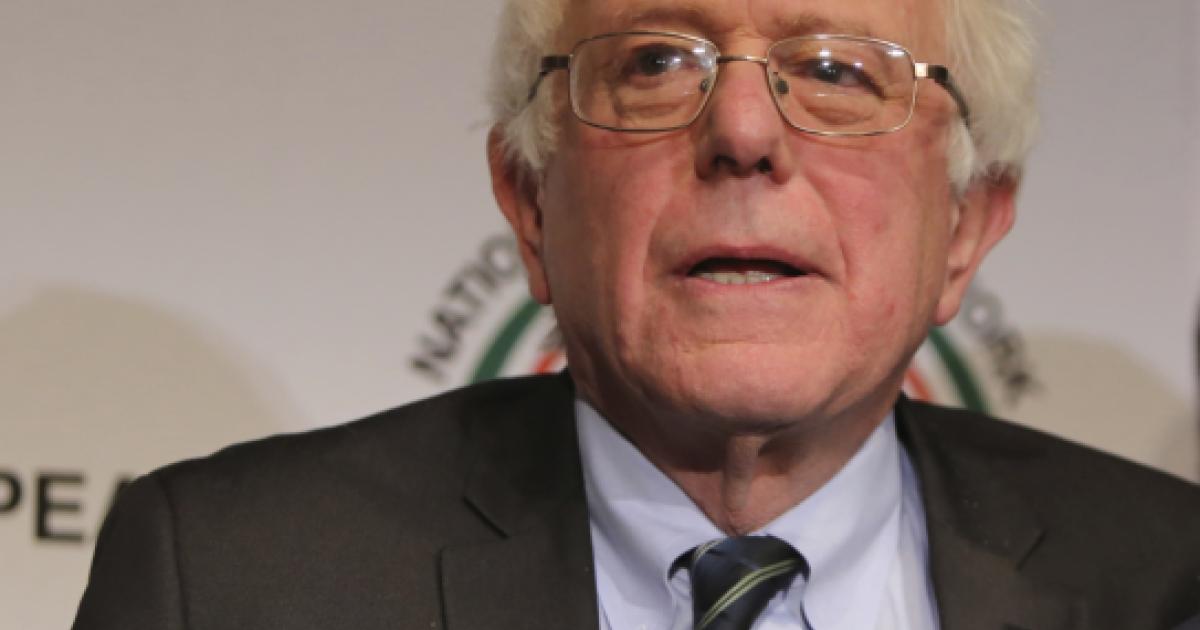

A fire of a different kind likewise consumed parts of California a year ago at this time: Bernie Sanders and the “democratic socialist” movement that threatened to take over of one America’s two major political parties.

On the first week of August 2019, the Vermont senator and presidential candidate brought his incendiary rhetoric to the Golden State. In a brief swing through Southern California, Sanders held a townhall meeting on affordable housing at a Northridge temple and staged a “Bernie 2020” rally on the campus of Long Beach City College.

However, not all Californians “felt the Bern”—and the promise of a brighter socialist future. Prior to the rally, Long Beach police arrested a local man for what was described at the time as “suspicion of making criminal threats and threatening a public official.”

Sanders would go on to win California’s March 3, 2020, Democratic presidential primary (this was two weeks before the state began sheltering in place), defeating Joe Biden by 8 points in the statewide tally. This translates to a difference of about 467,000 votes (Sanders lost California’s June 2016 presidential primary by roughly 365,000 votes).

How much stronger a candidate, in the California of 2020, was Sanders in his second coming? Look no further than Los Angeles County. In 2016, Sanders lost California’s most populous county by some 140,000 votes, underperforming by about a point and a half versus his statewide average. Four years later, Sanders beat Biden by more than 162,000 votes countywide, outperforming his statewide average by about 3.4 points.

And then came along COVID-19—and, in the California of August 2020, a question of the strength of Sanders’s “democratic socialist” movement as the Democratic party’s defining ideology moving forward.

As far as the 2020 nominating process is concerned, the Sanders presence in California earned the satisfaction of a seat at the head of the table, if you will. Rep. Ro Khanna, who represents part of Silicon Valley and served as a national cochair of the Sanders presidential effort, is one of three cochairs of the California delegation that ordinally would be attending this month’s Democratic National Convention in Milwaukee. (Normally a sitting governor chairs the state delegation, but in this case the progressive wing of the California Democratic Party flexed its muscle—and Gov. Gavin Newsom chose not to put up a fight.)

But thanks to the pandemic, that honor is damaged goods: delegates have been asked not to travel to Milwaukee; instead, they’ll cast their ballots virtually. Just as a suspension and then gradual “reopening” of the April-to-June slate of primaries denied Sanders the chance to drag out the process in front of the cameras as he did in 2016, so too will his followers miss out on a prolonged, symbolic outburst on the convention floor—Sanders’s delegates having resorted to histrionics at the 2016 Democratic convention in Philadelphia when their man officially conceded.

So what does the Sanders movement look like right now?

One view, obviously, is through a policy lens.

At that August 2019 speech in Long Beach, Sanders was full of promises of a socialist utopia: a “fair” distribution of income (“We have a corporate elite whose religion is greed.”); stricter gun control (“Assault weapons are weapons of war designed to kill as many people as possible. . . . We must ban the sale and distribution of assault-style rifles.”); raising the federal minimum wage to $15 and moving closer to a living wage; making it easier for workers to join unions; ending the gender wage gap; tuition-free colleges and universities (“We have to focus on the needs of working families, and canceling student debt is one of them.”); a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants; convincing other nations to surrender their weapons of mass destruction in exchange for a collective push on climate change; and, of course, guaranteed universal health care.

If you’re keeping score while sheltered in place, see how many of those ideas come to fruition in the nation’s capital by November 2022—assuming there’s a President Biden and a Democratic Congress available to enact such radical change—and how many scaled-down versions emerge out of Sacramento.

But there’s another way to view the progress of “Sanderistas” in California: winning elections.

In New York, the emergence of Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez—two years ago, she knocked off the number-four Democrat in the House of Representatives in a primary upset—heralded the rise of an angry progressive wing of the party ready to oust the old guard.

Not that the same will happen in 2020, but keep an eye on what transpires in House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s San Francisco–based district.

For the first time in her 33-year congressional career, Pelosi will square off against a fellow Democrat in the general election. Her opponent: Shahid Buttar, an attorney and self-avowed “democratic socialist.”

Among his issues: climate justice and energy policy (“We must transition our economy to 100% clean and renewable energy within the next 10 years.”); privacy (“Shahid will sponsor legislation to require law enforcement and intelligence agencies [such as NSA, FBI, and DEA] to secure a judicial warrant before searching or collecting information from or about Americans.”); liberty (“Having long embraced intersectional feminism, Shahid will be a stalwart defender of both reproductive freedom and justice. . . . All Americans should enjoy the chance to decide if, when, how, and with whom they grow their families.”); military spending (“Closing overseas bases and ending fraudulent corporate contracts would drive immense reductions in carbon emissions.”); foreign policy (“Prevent our military and intelligence agencies from contriving preventable future national security crises, as the CIA has sadly done relentlessly since it was created.”); plus a host of other topics.

Pelosi hasn’t debated an opponent since her congressional run back in 1987 (that’s two years before AOC was born); she’s shown no sign of wanting to do so in 2020.

And that doesn’t sit well with her opponent: “Shahid going 1-1 against Nancy will shine a spotlight on precisely how little she has done for the district in the midst of a housing crisis, an opioid crisis, and an out-of-control cost of living,” Buttar’s campaign manager told reporters. “The election will also reveal her role in exacerbating these issues, that remain at the forefront of voters’ minds both today and in November.”

Which is a shame, both for supporters of democracy and fans of irony: rare is the moment when Speaker Pelosi is the voice of moderation.