The Hoover Institution’s project on China’s Global Sharp Power and the Asia Society’s Center on U.S.-China Relations invite you to the launch of their new joint report The CCP Absorbs China’s Private Sector: Capitalism with Party Characteristics on Thursday, September 7, 2023 from 8:30 AM - 10:00 AM ET at Asia Society, Rose Conference Hall, 725 Park Avenue (E70th St.), New York City.

Report author and Hoover visiting fellow Matthew Johnson argues that recent regulatory crackdowns on some of the best-known firms in the People’s Republic of China (PRC), including Alibaba, Ant, Meituan, and Didi Chuxing, are not isolated phenomena. Rather, the CCP has launched a massive structural undertaking to harness private capital to restore the Party’s political authority across China’s economic landscape, while preserving the technology and capital flows necessary for Xi Jinping’s ambition of making the PRC the world’s dominant superpower. Following Johnson’s introduction of the report, a panel discussion will unpack how foreign investors, businesses, and governments can “de-risk” in an economic environment where state objectives come first and national security underpins everything.

>> Orville Schell: I'm Orville Shcell, and I direct the center on US China relations here at the Asian Society. And we're really pleased to have Matt Johnson here who's written this quite interesting, I would say very down in the weeds. But filled with an awful lot of sort of incontrovertible information about what's going on within the Chinese economy, particularly in the private sector.

This project is one of a whole series of projects we've been doing with Stanford's Hoover institution. And Glenn Tiffert at the other end is gonna introduce everybody on the panel and wrangle the discussion in a moment. And we've also done another recent report that just came out that I think may be available, if any of you are interested.

On the whole question of microchips in China and Taiwan and the US in that silicon triangle. And sort of the critical role they play on how everybody's tangled up with everybody else. And how elemental microchips are to the global economy, and yet how dependent everybody is on everybody.

And if things continue to separate, what's the proper pathway for it on that front? So you may find that of some interest. So it's been a long and wonderful collaboration, and with that, let me turn it over to Glenn Tiffert from the Hoover institution. And he will introduce the event and wrangle the panel.

>> Glenn Tiffert: Thank you very much, Orville. I want to start by thanking Orville and the Asia Society in particular for hosting us today. As Orville said, this is the latest in a series of collaborations we've had at Hoover. And in particular with our project on China's global sharp power with the Asia Society that have been extremely fruitful.

This report on semiconductors is the one that came just before this. All of these are available on the China CGSP, China's Global Shark Tower website, which is hoover.org CGSP-

>> Orville Schell: And on our website, please.

>> Glenn Tiffert: So you ought to be able to find it either way and downloadable for free.

And so our project on China's Global shark Power is really focused on looking at the way China asserts its power around the world in ways that affect values and interests that democratic societies care about deeply. We spend a lot of time looking at malign foreign influence at critical technologies and at research, security and integrity.

The semiconductors project fits into some of those buckets. But it also became clear to us that there were a couple of areas that needed deeper dives that others weren't doing such a great job at. And one of those was China's policies regarding data. And the second was China's evolving policies on the private sector.

So we reached out to Matt Johnson, invited him to join us to be a visiting fellow for a couple of years, and he authored a number of reports for us in partnership with the Asia Society on these topics. The data report came out in July, and the report on private capital just debuted last night, today really is the rollout for it.

And so Matt's gonna be here to introduce the report to you. And then we've put together just an a list panel, really, of people to comment on the report and I think more broadly on where China's economy is today and where it might be going. I want to say a word about Matt Johnson and our panelists before I turn it over to Matt to tell us about the report.

Matt Johnson is a visiting fellow at the Hoover Institute and research director at Garnaut Global. His expertise covers China's contemporary politics, strategic thinking and political control over the financial sector and private economy, you know Orville. And Stephen Sunyang has co-founded J Capital Research, which publishes highly diligence research reports on publicly traded companies.

She also writes a weekly research piece called China Primary Insight. Over 25 years living in Beijing and worked as an industry analyst and founded three businesses in online and print media and software. And of course, Yashung Huang is the epic foundation professor of international management and faculty director of action learning at the MIT Sloan School of Management.

Professor Huang is the author of eleven books in both English and Chinese on topics including political economy, regulatory transparency, historical autocracy, tax financing, and the history of reforms and strategy. His latest book, which just came out, the Rise and Fall of the east, how exams, autocracy, stability and technology brought China's success and why they might lead to its decline, was just published by Yale University Press.

So, Matt, over to you to tell us a little bit about the report, and there'll be a q and a section at the end so you can queue up your questions.

>> Matthew D. Johnson: Thanks, Glenn. Thank you to all of you for coming this morning. Thank you to the Hoover Institution and the China's global sharp power program led by Larry diamond, who is not here but is here with us in spirit, certainly.

And Glenn and Francis Hisgin, who have been key supporters of this project throughout its creation. And also Orville Schell and the Asia Society. I've received tremendous advice and guidance from Orville, who I've gotten to know much better in recent years and have benefited tremendously. So very glad to be with all of you today.

And just a quick word about the discussants who, you know really, in my view, are more like eminences in this field that I am putting. Tthe two fields really that this report intersects with. One is China's political economy, where Professor Yashan Huang has been writing for decades now, and I've been reading and learning.

Really was one of the first scholars to put politics into China's economy in a way that seems novel and important. And Stevenson Yang, whose work in the diligence field. For someone who spends a lot of time on research was an inspiration in terms of thinking about how to apply almost forensic tools to issues of where China's economy was going.

And how its firms behaved and what risks awaited the unwary investor. That's just a sense of, hopefully, how I position myself and how I position the work that I'm doing here. So basically, I just want to cover some of the key takeaways and use that as a way of teeing up hopefully.

And what I'm sure will be a more far ranging discussion on the state of China's economy today, which I imagine is what many of you are here to hear about. The fundamental sort of starting point for the report is a point that I'm sure will make sense to many of you, which is that China's economy has undergone a sea change in recent years.

And the sea change that it's undergone is that political forces are now even stronger in terms of the role that they play in shaping China's economy and shaping its direction and shaping, in a sense, the strategic behavior of actors. Within it, including corporations. The report located this sea change roughly 2020, which was when Xi Jinping gave a series of speeches to the Communist Party on what he called problems in China's or issues in China's medium and long range economic development, in which he laid out a strategy by which China would be not just growing and powerful and dynamic economy in the world, but would be an economy that exerted more and more leverage over the rest of the world and over the global economy in ways that would ultimately benefit China's national strength.

And these ideas were they began to be shaped into policy at around the time of the fifth plenum of the 19th Central Committee, in the same year when the party laid down the foundation for the current Five Year Plan. In which this idea of offensive leverage and also decoupling I wouldn't call it strategic decoupling.

In other words, making China less reliant on the rest of the world for key technologies, more able to produce those technologies for itself, really became embedded in the guiding policies that shape how the party manages the economy. You could hazard the argument that those priorities are now more important than growth for its own sake.

If you wanted to go further, you can say that Xi Jinping has basically indicated that those priorities are more important than growth for its own sake. And so within this plan, private companies and private capital have a role to play. The role that they have to play is they have to support the strategic objectives of the chinese communist party because it's a single party state and the party, among other things, commands the economy.

It's also the case, although this is a kind of separate narrative, that the party's become increasingly centralized under Xi. He exerts more sort of individual power over the system than nearly any Chinese leader before him. His view of politics, so to speak, is that all domains of society, including the economy, are, in a sense, part of the political system.

There's no real separation between politics and the economy in Xi's China, or between national interest and the economy in Xi's China as a result of these rewritten rules. We had a great conversation last night over dinner about, well, isn't it the case that the party has always been in the private sector to some degree, and this isn't necessarily new?

And that was a really provocative question and one that I thought about afterward, and I would say that what is new here is, for all the reasons that I just mentioned, we're seeing a kind of step change in the integration of the private sector with centrally directed economic and strategic planning.

So it's not that the fact of the party in the private sector is what's new. It's the degree, it's how the party serves as a medium for more deep integration between the private sector and the rest of the party state. And so this means that investors and businesses and governments are faced with a new situation with respect to China linked private companies.

I mean, some are domiciled all over the world, some have ownership that is largely foreign. So I think it would be a misnomer to call these in any sense. That's clear and accurate, chinese companies, but more like China linked private companies. And that situation is that they are increasingly coordinated and coerced by the party.

China has a rich and dynamic entrepreneurial tradition. That tradition is more and more again now harness the party aims. And there's been a pattern of CEO's and founders of some of China's most dynamic tech companies essentially being pushed out of their roles in recent years as the party has become stronger.

And also that these companies are being used in Xi's strategic struggle with the west. It's not just being driven by Washington, it's that Xi Jinping has an agenda of sort of pushing China forward vis a vis the west, vis a vis the United States in particular. Not just through economic growth, but also through defense, through surveillance, through propaganda, through technological self reliance, through economic leverage and through other tools.

And it's in support of these sort of sub agendas that private companies are increasingly expected to behave. So the challenges here, from a New York City and finance perspective, I wanna talk a little bit about the investment challenges also. One is that what the report really does from a research perspective, is it tries then to highlight how one would begin to analyze and understand China linked firms from the perspective of this change in how their behavior is coordinated and controlled, by going through the changes in the regulatory environment and in terms of internal structures and governance that are all part of this party absorption process that I describe.

I think the challenge for investors is understanding what all of this means for anticipating firm behavior from a perspective that is not solely profit maximizing. That takes into account the fact that as the private sector is still being reformed or rectified by the party, that this can result, and has resulted, and does right now, result, if you follow the healthcare sector at all, in ongoing crackdowns on private companies, that the party plays an increasing role in running the business, so to speak.

So I think it requires a new understanding of governance and who the real stakeholders in firms are. It requires being more aware of how party prescribed agendas interact negatively with Washington's regulatory effort to sort of offset the competition with China and the roles that private companies play within it by building new laws and capabilities that basically impinge.

Well, it depends on your perspective, but limit, either fairly limit or impinge upon these corporations, and then also the reputational risks that are involved when a company like Alibaba has to play a role in building out e governance and surveillance systems in Xinjiang, what that means for shareholders or other partners of Alibaba.

So these are basically four, I mean, to give a kind of consultancy style top line to it, you've got four kinds of risk here. You've got the risk that comes from firm behavior. You've got the risk that comes from government crackdowns in China. You've got the risk of Washington regulation, and you've got reputational ESG risk, as well.

As a result of this sea change in how the party is managing the private sector. I think the implications are basically that the baseline for research, which is part of what, again, this report tries to highlight, should change as well. That understanding political risk with regards to these China linked firms isn't just a matter of looking into ownership.

But is much more about internal structures, is about sectoral guidance that may not be obvious to offshore investors. Is about being able to anticipate political purges and where they may hit next. And is about other forms of external coordination, like military civil fusion data and cybersecurity laws, etc.

So that's the overview. I won't obviously read the report, or hopefully go through it in an overly schematic way, but just to lend a little more substance to what I've just said. I'm a historian by background, so I like narratives and I like dates. To give a very kind of simplistic timeline, I think you could say that in 2013 to 2017 Xi Jinping laid out and pursued a plan to rebuild socialism in China.

Not just in terms of control over information and history, which I think is often where some of the media attention and consensus tends to focus. But also on things like the party's control over the military and the party's sort of grassroots capacity, its ability to function organizationally as a centralized, Leninist, properly Leninist organization in which commands from the top go down to the bottom.

And feedback comes from the bottom and goes back up to the top. And that's how an authoritarian government functions in ways that sort of mimic some of the other functions of liberal democracies. So that was a big priority, and it was a priority that included in its scope the private sector.

And its aim was to prevent a Soviet style collapse of communist party authority on cheese watch and hopefully for the foreseeable future. That was explicitly the agenda that he came in with as first party secretary and then president of China in 2012, 2013. From that point onward, from about 2017 to 2020, the party's policy toward private firms, I think, could be generalized as pushing them outward, making them into globally competitive and globally recognizable brands.

This is the era of Made in China, 2025, that more and more value added items in the world would be produced by chinese firms. This was also the era in which Xi's military civil fusion agenda got off the ground. So at the same time that firms were supposed to get big and get strong, they were also supposed to be serving fairly discreet party state army technological agendas.

From 2020, you begin to see, I think, a break. And this is regardless of COVID, although arguably zero COVID allowed Xi to strengthen his grip on the economy in ways that might have been less likely otherwise. That's a hypothesis, but I'm willing to debate it. One was, as I mentioned at the beginning, the idea that China would now start to use this leverage over global supply chains to achieve other, in a sense, non economic ends.

And so we've seen this in Europe with Lithuania, we've seen it with Australia, and with South Korea. And other countries which have been targets of economic coercion for reasons not necessarily economic. And then you also, starting in 2020, as I'm sure many of you will be familiar, see the kickoff of a crushing series of campaigns.

Beginning with anti-monopoly cybersecurity, the defenestration of Jack Ma after he talked back to Xi Jinping about how the party viewed financial risk. And then the sort of very, in a sense, unsuccessful IPO of Didi and other sort of major events that signal that something deep was happening here.

That investors, if they hadn't gotten a hold of it before, we're now really gonna have to get a hold of. In 2021, Xi Jinping, in my view, began extending this agenda to capital markets. And so that's why the report talks about private capital as well as private firms, with, I think, the largely unnoticed opinion on strictly cracking down on illegal securities activities in accordance with the law, which was a kind of blueprint for a campaign lasting until 2025 that would essentially make capital markets much more instruments of party aims in the same way that private firms were now expected to be.

It got a little bit of press because there was some language in there that suggested that Vie structures might be made illegal in the future. But really, it was a much deeper and much more programmatic document than that. And so in that year, we saw Xi's control over private companies and capital evolving.

Then in 2022, so bring us right up to the present, another wave of meetings between party sort of the Politburo standing committee. And it's, so in other words, the top party leaders and private sector tech leaders. Basically echoing things that Xi Jinping had been saying since 2020, which amounted to get with the national program here.

Your ability to come back into the fold is gonna be dependent on the degree to which you support our political and national strategic agendas. And then by 2023, with the ending of zero COVID, you also got the next stage, which is sometimes referred to as normalized supervision. Meaning basically that the crackdowns, at least for some major subsectors of the private sector were over.

But nonetheless, the party presence was not going to go away. This wasn't a sporadic, fitful event, now it has an institutional legacy behind it. And that's basically the narrative that the report goes through. And then there's a fairly forensic and detailed back end, one really dealing with changes to the environment around private firms in China, both China and also foreign.

And in China with respect to, we could call it four kinds of integration, legal integration. So how companies and individuals are legally compelled and obliged to support the party and its agendas, digital integrations. So how systems are integrated into China's increasingly robust big data and ICTS systems, which was something that we covered in the first report on data.

Financial integration, this one's a little harder to track. But I'm not among those who think that Xi's common prosperity campaign is all hot air. I think that common prosperity is, anecdotally and in ways that can be documented, a way of transferring private wealth to the state. Basically, when the party and the state security forces that underpin its authority say so.

And that there are demonstrable consequences for not replying to these requests. And then finally, military or national defense integration, which would be a subject for future research also. But this so called new national system that Xi and some of his not political figures that are well known outside of China.

But his key supporters and almost organizational architects within the party are keen to build. That would put private firms much more squarely and formally within state planning structures related to technological modernization. The report also goes into the firm-level changes, new rules for individuals and corporations starting in 2020, the imposition of-.

Or the sort of reactivation of the United Front as a tool for coordinating non party employees and executives in private firms and recruiting them politically. And then also the reemergence of the Central Commission for discipline inspection, or the CCDI, as the coercive tool by which both party and non party members are made accountable for following party rules.

One point that I would obviously wanna make here is that it's extremely important not to view China in the sort of aggregate as a kind of homogeneous, party-controlled mass, that's obviously not the case at all. But then what Xi and the party have done to sort of strengthen more totalistic forms of organization is to step up the punishments for noncompliance.

And so organizations like the CCDI, which is more or less even within the party, an instrument of terror, now have scope to, and have purview more broadly outside of the party as well. The report concludes with two case studies of firms that I think are the fairly well known and topical.

One is Alibaba and Ant, where the research mainly walks through Alibaba and Ant's internal governance structures, which do not show up in its investor materials or really in the public image of the firm at all. And Alibaba's what I would call party work, basically building systems and infrastructure for the party state, primarily within China.

Although with respect to fintech and data centers and cloud, not exclusively inside of China, in fact, increasingly outside of China. And then secondly, ByteDance, which I've written about in other venues as well, which is an extremely complex company. But I think what sources say, and of course, sources are limited in kind of key ways.

But I think when you put the open source evidence together, the pattern that you see is that ByteDance and TikTok are much more one company than they are multiple companies. And this fact is more or less deliberately obscured in testimony, etc, by representatives of TikTok. And that the company, ByteDance itself, is fairly deeply integrated into China's internal propaganda system.

And also plays a role in development of surveillance technology, does propaganda for the military, works with the Ministry of Public Security, and is increasingly scrutinized for its political interference activities abroad. And so the conclusion would be that we are basically seeing the evolution and emergence of a new type of corporate organization, one that is very hard to understand, as I said before, through the lens of ownership.

If it has these sort of hybrid party and private qualities, it's not ownership that's gonna tell us whether firms are more or less shaped by the party and shaped by the government, it's other structures. And that's really the point of the report, is to detail all of these other structures that I think from a diligence perspective, potentially from a national security perspective, analysts, investors, others should be more aware of.

And that also, I think the flip side here, and we're seeing this experiment play out right now in real time, is these entities are now much more vulnerable in ways that they weren't before, if you wanna look at it that way. They are not, it seems, as dynamic and as relatively unconstrained in the pursuit of innovation.

They have to serve agendas that are not necessarily the agendas that their founders or investors or others intended. And they are increasingly caught in a political and regulatory crossfire, and ultimately in a kind of brewing geopolitical competition between Washington and Beijing and other national capitals as well, thank you.

>> Glenn Tiffert: Thanks for that great introduction, Matt. And I encourage you for greater detail to look at the report. We've asked our panelists to offer some reflections on what you've heard and on the report, and why don't we start at the end and work our way forward?

>> Orville Schell: Well, thanks, Matt.

I think, having an affection for history myself, I think what's so telling about some of the findings of this project. Is that the deep way in which a revolution such as China had, or Russia or the many, many decades of sort of revolutionary ideology and organization. How enduring those things are and how difficult it is, even with the most extreme and tectonic forms of reform to ultimately escape and vacate those mindsets.

I've been studying China for a long, long time, first went there when Mao was still alive, the cultural Revolution was still going on. I remember very vividly those inflection points when Mao died and the reform movement came, and we all thought, well, we're in a new world. And we saw the slow recrudescence Of private enterprises, of much more sort of open media, academic freedom advance, etc., etc.

And we thought that China had kind of turned the corner and now was headed off in some different direction. And instead, what I think we see with Xi Jinping, who is himself, his formative years were during the cultural revolution. And we get into that, but it's a fascinating story about him and his father.

And his father was accused of being a counter revolutionary, and poor teenage son. Everybody wants to love and respect their father, and yet here the father was in the black category. So I think Xi Jinping, in a curious way, is a vector for an earlier form of politics, of being in the world of economics, all of these things.

And I think what we have here in this very telling and well researched document is a sense of how it is not easy to escape one's historical past. And what we now see happening is the old world of control, one-party state, Marxist, Leninist, economist. Xi Jinping, said, north, south, east, west, the party is central.

You don't really need to read much more than that to get the essence of what Xi Jinping is all about. That means the economy, too. And so we are at this world where China had rather recklessly, in my view, joined the global economy. We thought, all was good, we're heading in the right direction here, we're converging.

Things will slowly change and everything will become more soluble with everything else. And here we find Xi Jinping galloping back in on his mount to regroup the Chinese economy, which is at the center of the global economy. And in fact, I think if you look at it carefully, you see that the real decoupler in all of this, it's not that we aren't having such tendencies ourselves in the west or the liberal democratic side of the ledger, but the real decoupler is Xi Jinping.

Why? Because fundamentally, his old sort of Marxist, Leninist formative genetic material has never trusted the West, never trusted capitalism, never trusted democracy. Never trusted that outside world that he grew up viewing as antithetical to everything that China then stood for. Now, obviously, it's a little more complicated than that, but I think we are seeing a kind of a return to a form of sort of politics, economic organization that is not a complete model of Mao Zedong by any manner, but it is a reminder that these revolutions cast a long, long shadow over our country.

And remember this, that when Mao Zedong set up the People's Republic of China finally, in 1949, of course, he'd had many years running the Communist Party. He adopted a system from the Soviet Union, lock, stock, and barrel. And even during the reform years, that system, how the government is organized, how the party interacts with the state, how it all set works up, was never altered.

And so it was not difficult for Xi, when he sort of came back into power, to use this structure to implement some of the reforms that we've just heard about from that. So those are just some sort of thoughts that, because I'm not an economist, but I do look at China's trajectory.

And having been one of the very hopeful people, all of you probably shared that sentiment, that China was somehow gonna manage to vacate its Maoist past. And here we see it in cryptic ways, returning. It's a reminder that you don't just have one Deng Xiaoping arrive on the stage, wave a wand, and you get rid of many decades of deep and very traumatic revolutionary history.

>> Glenn Tiffert: Thank you, Ann.

>> Anne Stevenson-Young: Me, so that's a fascinating historical perspective and makes me think, however, I have a darker view of the party. Perhaps not surprising. So I think that when China emerged from the Maoist era and came into the world to develop these new relationships, it was similar to the way a train couples its cars.

And it never really, really integrated with these institutions, but instead developed a sort of interface in order to be able to talk to the WTO and the GATT and the UN and so on and so forth. And now it was always going to decouple. Once the party had acquired enough power, enough resources, enough money, that it was always going to decouple.

Because the most important thing to the party, when the reforms began in 1979, 80, the reforms were always provisional, step by step, crossing the river by feeling for stones, and so on and so forth. Which means that the party had to be in charge, right? When things are provisional, when you don't have a roadmap, when you're not going toward a particular system, then somebody has to be in charge of making the decisions, and it's the party.

So I think that this fits within the communist ideology as well about how capitalism is a transitional stage. I don't think that's tremendously important to the CCP, however, it's useful. And I do think that capitalism and the reforms from 1979 through one can really say 2009, were always meant to be temporary in order to bring in more resources.

I think that the report is a fascinating, thoughtful and very, very professional sort of considered compendium of policy and information about modern China. I think that it extends too much. It believes in Xi Jinpings power too much. I think that Xi Jinping, actually, we have a very long history to look at with China, with China being closed, being paranoiac, with China rejecting connections with the world, and how unsuccessful thats been for China in extending its influence internationally, in developing domestic technology and in all of those domestic agendas.

What we see with Xi Jinping is a reaction to the weakening of the party throughout the expansion of the economy, and so a determination to recapture the party's power. I think we see that with, And the party specifically, not the government's power, I think that that's the purpose of the common prosperity program for example.

All of the channels that you see developed in the common prosperity program are about bypassing the government and using the party to collect resources from the public or from local governments or whatever it might be, or from companies and distribute them to party channels. Many of Xi Jinping's policies are about that, building the party structure, strengthening the party structure, making sure that billionaires like Jack Ma don't become Donald Trump's and start to develop into internationally powerful oligarchs.

And to that extent perhaps he's been quite effective in strengthening the party and making it last longer, in making China a stronger place and extending its influence internationally and extending its technological prowess I think not at all.

>> Yasheng Huang: So maybe I'm the more charitable person on China on this panel, and so let me start from that, first of all, I thought the report is really well done.

It goes into details about these two case studies that are just fascinating, the party person in the Alibaba group, Mr. Xiao, I thought the description is really very detailed, and I didn't know much about that. So it's really just very informative, but be more useful, maybe I'll raise some questions, I think there are two kind of big questions.

One is that if the report is correct, that the relationship between these high tech companies, private companies, and the CCP was so collaborative and so collaborative and fused with each other so closely, then why would you crack down on them, right? So, I mean, that's kind of sort of big question that I don't think I have a good answer to and the private sector companies were helping the CCP.

And if you think about the health code that was unveiled very, very quickly in the aftermath of the virus in Wuhan dhe, it was Alibaba and Tencent that came up with the health codes. That in the short run before the vaccine was developed, they gave government the control capability to quarantine the population in a controlled and targeted manner.

Later on, it was weaponized but we shouldn't judge what happened to Shanghai and what happened to what happened in China in 2022, we shouldn't use that to judge the earlier action that they took. Which I thought was effective and justified on public health grounds, because you didn't have the signs and you only can rely on administrative control, whereas the West can only wait for science, and science takes time.

So not just the discovery takes time, but also the implementation takes time. So if the private sector company, plus the revenue raising and the development of the private sector also elevated the value of the real estate, right. I mean, all of these obviously results accrue to the society, accrue to the Chinese people, but they also accrue to the Communist Party in the form of tax revenue, in the forms of dividend payments, payouts, and in the form of land sales, revenues from the land sales.

And then in turn, the government and the state used these resources to build infrastructure and to fund industrial policy, high tech parks and all these things. So just incidentally, my view of Chinese infrastructure and industrial policy is that they are really the result of economic growth. They are not the reason for the economic growth, and it's very often mistaken as the cause rather than the result, but that's a side view.

And the report into details describing the collaborations between the government and Alibaba and private sector companies. For sure, some of these collaborations are unusual if we use a kind of a market economy perspective, but others are quite a innocuous, right, quite common. Alibaba helped the Hangzhou government with software solutions to their traffic controls, hospital optimization.

So if anybody has been to a Chinese hospital, which I don't recommend. But if you happen to a Chinese hospital, you know what I'm talking about is basically, in the Chinese hospital you have to know before you see a doctor what health issues you have, because it's so divided, very internal medicine and surgery.

So you have to be a doctor to know where to go, and Alibaba helped the city government optimize these procedures using data to inform the patients. It doesn't solve that problem, but at least it optimizes the waiting time, so these are, in my view, unquestionably public good effects and traffic control, right.

So the Chinese traffic can be horrendous and to optimize traffic, I don't really see any problem with that. And in other contexts, we would say that these are public private sector collaborations and partnership that we often praise and advocate, right, so I think it is important for us not to go overboard on that.

The Xijing and those things, yeah, for sure, but those things happen much later, right. So whereas those other collaborations have been there for many years, and I wouldn't lump them together, right. So, I think it's important to distinguish the sort of the evolution of the nature of these activities from kind of innocuous public private sector collaborations to more control and surveillance.

And, so there's a timeline to that, and the other is that it is true that these private sector companies have party. The party presence, but you can sort of make the argument that the effects go both ways, right? So yes, it is for the state to get information, to have some surveillance within the company.

But it is also true that, in that type of economy, where approvals by the government for investment projects, the government has controls over finances and all of that you do need. We can criticize that setup, but given the setup as it is, then the government, then the private sector companies do need some sort of access to decision making players in the government and to have a party person within the company can serve that purpose.

Obviously, the same presence can go in the opposite direction depending on what is the broad political imperative, right? So if the broad political imperative is for economic growth, then probably the direction effect comes from more from the company to the government. If the political imperative becomes political control, then the same mechanism can be used to achieve exactly the opposite effect, which is the government controls the company.

But that is not a mechanism that is kind of interesting and novel and unique. It is really the broad political imperative. So I think we go back to oval and stevens view this kind of the evolution of the broad political objective rather than the mechanism, whereas much of the attention in the United States is about the mechanism, right?

To some extent that's totally understandable, because we already know what has happened to the political imperative. Then we look at the mechanism, but I think we do need to be careful about that mechanism and the due effects, the dual functions that it has historically served. So let me talk about Jack Ma a little bit.

It is true that he made some critical comments about the Chinese Financial System, and then there's a close correlation between when he made those comments and when the IPO was shut down. But if we look at Jack Ma in his sort of history, it was reviewed in the Chinese press that he became a communist party member as early as early 1990s and 1980s.

And he has said many, many things that were quite positive about Chinese political system. And he said those critical remarks about financial system. He said those things many, many times before. So obviously, it is not the novelty and the bravery of those comments that led to the shutdown of the IPO of the ant group.

It was really something else, right, so I don't really believe in the view that, that somehow he was challenging the party. There's actually good social science research that shows that private sector entrepreneurs in China actually didn't demand political participation, and they just didn't. Whether or not that's opinion survey whether or not that's true or not, we can debate.

But at least on the surface private sector entrepreneurs, big and small, including Jack Ma, believe that the best way for them to move forward in that system is to have a bargain with the government, whereby they will just be making money, but then they will not challenge the government.

So I just don't see the crackdown as a response to some sort of private sector challenge to the power of the CCP. Let me end by raising the second question, which is that it is to some extent motivated by the same puzzle that I have for the first observation.

And the second observation is, so the name of the project at Hoover Institute is sharp power of China. So let me kind of use that to ask the following question. If the Shark power is the thing that they want, why do they do things that have blunted their power?

So we know that now the economy is slowing down, the private investment is slowing down, there's a massive flight of capital. So if you really want to increase your Sharp power, wouldn't you want to grow the economy? Wouldn't you want to overtake the United States in terms of aggregate GDP?

Wouldn't you want to develop the technologies? And yet what we see is that they go after the high tech companies. They take measures that have a very predictable effect on economic growth, and they take measures that have very predictable effect on reducing the confidence of the consumers and the private sector entrepreneurs.

So it is genuinely puzzling that for a country and for institutions CCP, that is commonly portrayed as having this grand design to overtake the United States to challenge the western economic order it is, I think, genuinely puzzling that they have done these things that have achieved exactly the opposite effect.

Right, so

>> Orville Schell: I do hope you're gonna answer your own question.

>> Glenn Tiffert: We'll get to that.

>> Yasheng Huang: Okay, on that, let me shut up.

>> Glenn Tiffert: I wanna give Matt a couple of minutes to respond to the comments, and then we'll have a moderated panel discussion and Q and A.

>> Matthew D. Johnson: A lot to digest here so it won't be point by point, but that should probably allow us to get more questions and discussion in. I mean, really I would say to the, to the first set of observations from Anne that I think that contrasting of interface versus integration is really fruitful, interesting and something to draw more attention to.

And really you can see it in China's economic policy today in a more formalized sense, with the idea of a dual circulation economy, where, in essence, there are two sets of structures and two kind of cycles of economic circulation one for the insulated and protected domestic economy and the other for the parts of the economy that has to interact with the rest of the World.

So that seems very astute. My analysis is somewhat Xi-centric. That is an analytic choice. I see in the research that I do and the analysis that I do, I see Xi and the Politburo really being upstream of all of the major decisions that have been taken, and that's almost definitionally true.

But then you also see those decisions being implemented in ways which I think are very immediate and have real effects. At the same time, I do think it's a very important caveat that this isn't a plan for reasons that we've just heard raise. This isn't a plan that is destined to succeed, that because Xi envisions a more totalistically unified political, economic, social, et cetera system all kind of fused into one, that he's going to be successful in creating that system.

But I do think the intent is there, and it's built a lot of momentum over the past several years, I think, in particular during the era of zero Covid. But then, on the other hand, the era of zero Covid was an era in which we saw some of the first really sharp, critical pushbacks against Xi as well.

And so it's not to say that this agenda doesn't have costs. To the longer list of points raised by Yashung here, I think the, you know, response would be what really stood out to me, which I also wholeheartedly agree with, is the sense that it's not the fact of party organizations that has changed.

It's not the behavior of private entrepreneurs that has changed. It's not even the role that private sector companies have played in supporting government agendas, sometimes in very benign, developmentally oriented ways that have changed, like sorting out public health and transportation and other issues. But there does seem to be an unmistakable shift in trajectory and environment.

And, you know, the politicization of everything, basically, that makes all of those, you know, facts on the ground take on a very different meaning. With Jack Ma, for example, wholly agreed, no doubt. It didn't come back to that particular opinion, but there is something about that particular opinion at that particular time.

That's what was different. He delivered those remarks right after the most recent meeting of the Politburo, had said that financial risk, black swans, et cetera, were one of the biggest, most threatening issues facing China in that moment. And then Jack Ma gets up and is like, you guys don't understand.

He's talking about Xi Jinping directly. And in that moment, that carries a very different set of consequences than it would otherwise. That being said, we don't know the exact reasons for why he's faded, so to speak, or was faded from the scene, which is, I think, a very important point and one worth taking.

So all I can say is thank you. Thank you for your thoughtful reads. Thank you. And this is very much a sincere expression of gratitude for the work that you've done. It's been an inspiration for the work that I've been doing more recently. Thank you for your insights concerning this report.

>> Glenn Tiffert: So I'd like to start our panel discussion with maybe Yashung's question. Really, I think it's a great one. One could argue that many people are often rational. Where they differ is in their preference orderings, right, and explaining why. First of all, China, Matt locates the shift in around 2020.

Others might put it someplace else. But if you look at China, and if you look at Xi Jinping, from 2013 to 2015 to 2018, they seem to be going from strength to strength. Xi Jinping, in particular, was presiding over a world that it was almost imperial in a way, and the sun shone very brightly upon him.

That has really changed. And it isn't just the economy. It's the way wolf warrior diplomacy has played out. It's across the board, really. And the world is seeing a sort of a new light on China. And so understanding, actually, why China seems to be sabotaging its own interests in more recent years is, I think, an excellent way to start the discussion.

And I'd be curious to what our panelists think about that. Why is China undermining itself?

>> Anne Stevenson-Young: Well, if I may just say something, there's a great book called why Nations Fail. I can't remember the author, but he goes through many, many contemporary examples of countries that are dominated by very centralized political systems where the political system, the political and elite clique at the top of the system demand control of the economy and of politics.

And he talks about why those economies weaken and eventually fail. I think that's what we're seeing in China. I think that control is more important to the CCP than growth. I don't agree, actually, that the CCP ever had much of an international agenda. I think their agenda is, number one, remain in control.

Number two, control international energy resources, and number three, be left alone. That's basically it.

>> Orville Schell: I mean, I think this is Yashong, and I can't wait to hear your answer. You raised the question of questions. Why is this happening? Why, when Xi Jinping had such a good thing going, he had every nation in the world eating out of his hand.

He had nine presidential administrations in Washington supporting engagement and saying, we don't see China's rise as a threat. We're all teamed up, WTO, most favored nation status, etc., etc. And I think, I don't have an absolute answer here. But here, sadly, I think this is where personal leadership actually counts, particularly when a big leader is in, a big leader Kultur.

And writing himself very large across the landscape. Now, we live in a total chaos of democracy here. Nobody gets to write themselves very large. They try, but nobody actually succeeds very well. And it's a form of sort of congenital weakness, too. But the alternative is congenital strength aimed in the wrong direction.

And I fear that China may, and maybe, and I've written about this somewhat tentatively, but we may be witnessing, I hope it's not true, but a kind of a terrible tragedy. Or an immense amount of resources, success and acumen, and extraordinary suffering and hard work by the Chinese people to accomplish what is, I mean, any of us who've been there know what an extraordinary thing this is.

The sick man of Asia once upon a time, what they've done, why, as you've said, Yasheng, and I do want to turn right back to you, why did they do it?

>> Yasheng Huang: Clearly, it was a mistake for me to you-

>> Orville Schell: But when you better than any of us, I think, ought to have some insight into what's going on here.

>> Yasheng Huang: Well, maybe not insight, but at least speculations, and that's the best we can do. By the way, the authors are Darren Osmoglo and James Robinson. Right, sorry. And historically speaking, we have witnessed economic reversals throughout history, right, not just in China, but also in Europe. If you look at globalization index, and the world as a whole had greater extent of globalization around the first world war than it was later on.

And then the world didn't recover to that level of globalization until the 1960s. So I think the reversals are easier when the only dynamic is on the economic side without the political and ideological and intellectual changes. So if all you have, and this is why many, I would say, business people and economists, got China wrong.

Because they only look at the trade or GDP ratio, the FBI to investment ratios, and they say this is one of the most open economies in the world. And then they all dismissed politics. And I thought that was just totally wrong, even wrong to say these things in the 1990s, sort of at the height of when China was emerging to be a globalization player.

So this is getting to the speculation why it happened. New York Times did a piece maybe three days ago, four days ago, on how she managed to establish one person rule and went down the list of the things that he did. And it was very good at describing what he did, it did absolutely nothing in terms of explain why he was able to do these things.

And I think the reason that he was able to reverse these things with apparent ease, at least in my book. In my book that just came out. And by the way, this is a commercial for the book, just to make it clear. So I argue that there's a straight line between Tiananmen and Xi Jinping.

And what Tiananmen did was, it basically demolished the emerging political decentralization. That was more than what I knew before I began to do this book. My last book was about 1980s, but my last book looked at decentralization at a local level. But this time around, I came to the recognition that there was substantial distributed nature of the power at the top level, and Tiananmen basically got rid of all of that.

One of the most important institutions that it got rid of, that would have, in my view, long-term effect, was the central advisory commission. And that basically had the retired revolutionaries at the time when it was operating, it was criticized as a bastion of conservative leaders, that's all true.

But the thing is, if the institution remained, it could have changed over time, right? You could have retired leaders with an institutional voice and institutional platform to voice their opinions and to provide their inputs, that totally disappeared. And just imagine in 2018, when she wanted to revise the constitution, if there had been such an institution, I think the outcome would have been different, right?

So in my own view, if you look at the Chinese political history for 2000 years, it always had a gravitational pull toward autocracy. The only issue remaining is whether the aspirational autocrat encounters resistance or not, that's the only. So the mathematical certainty is that you're gonna have autocracy.

The less certain question is whether or not that person is going to encounter resistance. In the 1980s and 1990s, you had a level of resistance. Now you did not, in part because of the demise of these power arrangements. So, we couldn't, I don't think we could really predict very precisely what Xi was going to do, a lot of it was contingent history.

And I think he probably began to do these things step by step, and he was probably pushing the envelope. And he felt that he could do lots of these things, maybe to the extent that was greater than he expected. So, I think that, and the tragedy now is that, these are one way street, right?

You can't really pull back. And if you have purged 4 million officials, many of these people are very powerful people, were very powerful people in the political system, and they probably had relatives, they probably had supporters. So times 4 million by four or five, the anti-corruption campaign has antagonized 60 million people, 20 million people.

How do you pull back from that? So, I think that's the dilemma facing the leadership today. If they pull back, then there's going to be backlash, right? And if you don't pull back, then you have these economic consequences. I think it will be very interesting a few years for people like us to see what is going to happen.

My only prediction is that, it is not going to be a sort of normal four or five years next, it's going to be pretty eventful period of time.

>> Glenn Tiffert: I would love to ask the panelists more questions, but I want to leave room for Q&A. It seems to me that those were extremely astute observations, particularly because they invite us to re-examine the legacy of Deng Xiaoping in a way that I think is more nuanced than he's often remembered.

And if you do that, it begins to change the kind of linear projection of the journey that China has traveled in the last 40 years. And it makes it a much more ambivalent, I think, trajectory, one that Xi Jinping actually is perhaps more at the center of than an outlier, perhaps, and that's food for thought.

But also, I think Yasheng did not really develop the point, though it's implicit in what he said that the takedown of members of the standing committee of the Politburo, for example, early in Xi Jinping's ascension to power and then the anti corruption campaign, really leave him no exit strategy.

There is no way for him to walk safely off the dais because he set the precedent now that the knives come out, the minute you show weakness. And so the next five and ten years, I think, will be interesting times. They might be extremely fraught times, too. And so hold onto your hats.

But we have a microphone, I think, here in the room. That's not right? And so, yes, if you have questions, I invite you to come up to the microphone as this is being recorded and we want to capture it. So thank you.

>> Speaker 6: Thank you very much. I look forward to reading the report.

My question is, if you're a shareholder of Alibaba, where do you see Alibaba going forward vis a vis the declining situation in China versus its economy? And if you have to again predict something, you have to set policy. How are you going to react? I mean, it seems to me you've set up the dilemma, but you don't have a prediction as to what US policymakers should actually be doing to confront the situation.

Thank you.

>> Glenn Tiffert: Shall we take two?

>> Speaker 7: Yeah. Okay, thank you. Thank you, this is great, Orville and Yashuan. Thanks very much. So a couple of things. One, I guess maybe related, how much do you see Xi and/or the communist party tacking with the latest economic downturn? Kind of as an outgrowth of that, if this downturn ends up being structural and not cyclical, what will that mean for the policy?

And second, kind of related to the last question, what are the concrete implications for the outside world? You mentioned that this will help in terms of the research, analysis and framing the understanding. But kind of what do you see actually happening and how will that affect the behavior for other countries that are dealing with China?

Thanks. Sure.

>> Glenn Tiffert: And please don't hold back in the answers and your thoughts. Who'd like to start?

>> Matthew D. Johnson: I mean, I can kick off just to get us rolling. I think, and I'll try to keep it snappy in terms of what's next for Alibaba shareholders. Look, investors want to know that the crackdowns are over.

They want to know that normalized supervision, even though it may be a drag on performance, although for the reasons that Yashung raised there, could just as easily be a kind of dividend for being seen now as a more compliant company, we can expect, have seen, in fact, bounce back.

But I think the view from Beijing is still that they don't want these firms getting stronger again. And so the way that the regulation is moving is to hive off the individual businesses. And this is why Alibaba was broken up into six component entities. And to hive those businesses off so that as institutions, these especially bigger tech conglomerates don't again become more powerful.

What that's going to look like, I don't know. The optimistic view is it means more ipos. It means that Alibaba still somehow retains all of the synergies that it possessed in the past internally, although I see a much harder case there. And it means that the company can continue to innovate and move into new sectors.

Although there, again, I think the signs from Beijing are somewhat the opposite. It looks to me like they're discouraging firms from becoming too proficient across different sectors, because that was the original problem. The whole premise of anti monopoly was that these tech firms have become too big. At the same time.

What again Beijing is trying to offer in return is support for going out and going overseas. So presumably what lies ahead is some kind of next phase in overseas expansion. And those are definitely the kind of signs that I would be looking for. Less reliance on China's own domestic economy.

But we'll have to see how that plays out, because it gets to the second question, which is how are these firms going to be regulated overseas? The more Beijing pushes on them to support strategic objectives, which, while in the past may have been more benign. Let's build out ICTS in developing countries.

But when that turns into surveillance, eavesdropping, et cetera, then the response is obviously going to change. As to what the policy responses should be, what the implications for the wider world are. Look, I mean, I think we are now, and this is another kind of deep subject of conversation, ongoing.

We're seeing an era, the emergence of a kind of new stage. And it goes to the point that the next four or five years might be interesting, are likely to be interesting in which you have capitals that openly and explicitly see each other as competitors, but firms and investors and private citizens and others are sort of caught between these hardening positions and have to figure out how to proceed, what's a safe investment versus what's a more politically complicated or perhaps reputationally harmful investment?

That's the status, that seems to be where the trend line is going. It would be great if the recent diplomatic overtures the Biden team has sent five or six officials over to Beijing, or it's been five or six official visits, really began to help warm up the environment again.

Since zero Covid in particular, it's been pretty chilly and what comes next? I think we'll know within this year whether US China relations are going to take a positive turn. There's been no we're almost at a high point of engagement in terms of visits and in terms of language.

But now the next step is know the next shoot and drop, so to speak, is what actually comes out of all of it.

>> Glenn Tiffert: I want to be sure we can get to the other questions in the queue, so please.

>> Speaker 8: It seems to me there's a tried true path, right, for someone such as Xi Jinping, and maybe he's in the third inning of.

This and Putin is in the seventh inning of this and do you call it Kim, is in the fourth or fifth over time. And it is once you've consolidated power. Once you've created the enemies that you need to consolidate that sort of power from just a broader communist state, you forced yourself into a place where you're always watching your back.

And in fact, you have to further consolidate, you have to further stamp out resistance. So it isn't necessarily what Jack Ma did anything different, is the circumstances had changed personally for Xi Jinping and the power he had now, the ability, but also the requirement. And if you look at what happens to those economies over time, once again, the once great economy of North Korea is now what it is.

And Russia is becoming what it is, and China has sort of crossed the hump. It seems to me that there's also an ability in a government like that to constantly preach openness and that the worst is over and yet constantly work towards something completely different. And we as Americans are just non-Chinese.

Looking at that, shouldn't we be more inclined to look at the examples of Russia and North Korea over the course of the next 25 years? Not expect this to end anytime soon, but we should pull back, and we should put almost no confidence in anything that the Chinese government says when it doesn't have to state its own objectives.

>> Glenn Tiffert: Okay, well, one more.

>> Speaker 9: I'm very curious about, effectively those fines that the government levies on these private companies. The report highlighted, I think a $50 billion investment by Tencent. I'm curious sort of what you think is the mechanism, how do you arrive at that number? Is it a, Daniel Zhang or Pony Ma's?

Since you're their advisors and asks them, how do I get into good graces of the government? Or is it a government official or government committee or party committee coming down and being like, okay, here's the shakedown, pay it, you can stay in business. What's the mechanism? And I think what's interesting, what the impact of that answer would be.

Does it happen over and over again? Is it predictable? Is it, well, not fine, just a one-time regulatory crackdown, or is it gonna be reoccurring? Thank you.

>> Glenn Tiffert: Yeah, well, actually, let's give Orval.

>> Orville Schell: I'll give you a very quick answer. You say, what do we do about this sort of gathering, sort of autocratic confederation?

I think in this sense, Biden is doing a reasonably good job. He's trying to deter. He's arching his back, but he's trying to keep the door open. We have to remind ourselves that China has always had more inflection points. There are always more inflection points ahead. It will change when we don't know, but we do need to be ready in case that happens.

But I do think the old era of flexible authoritarianism for the moment is over. So I'd say deter, arch your back, and keep the door open.

>> Glenn Tiffert: Ann or Yashem with regard to the second question.

>> Anne Stevenson-Young: You wanna talk about mechanisms or whatever you wanna discuss. I was just gonna put a plug in for your, when was it, 1998 book, the one on Red Capitalism.

>> Anne Stevenson-Young: I thought that was the most seminal study on this post-Tiananmen period that I have read, it is absolutely critical to read. Anyway, go ahead.

>> Yasheng Huang: Thank you so much. It was 2000.

>> Anne Stevenson-Young: 2008, sorry.

>> Yasheng Huang: But that was a revised edition. I was a teenager in 1990.

>> Anne Stevenson-Young: I wasn't, I was already in China. Yeah, I'm revising that book now and get through some of these issues during the Xi Jinping era. Let me sort of start with the Alibaba question. First of all, I'm sorry that you're a shareholder of Alibaba.

>> Yasheng Huang: But the way that I think about that company is that there are two things that we need to think that would impact your returns from investments in that company.

One is the baseline and the other is the deviations from that baseline, right? So the policy crackdowns, the political shocks, and geopolitical tensions, essentially are posing forces that will lead to deviations from the baseline, right? And that's a little bit hard to predict, right? Because a lot of it is policy, political driven.

But the bigger question I believe is the baseline, what is the baseline value of Alibaba today as compared with the company many years ago? I would argue that the baseline fundamentals of that company have been weakened substantially, right? So if you think about what that company did and why that company prospered, it served very valuable functions of linking suppliers with foreign buyers in the early days of that company.

And then the Ant Group was incredible in terms of developing the fintech technologies that enabled the company to match demand for credit with the supply of the credit. To those companies and individuals that don't have the necessary asset base to qualify them for formal financial service. And those functions are now much less as compared with them before, right?

So essentially the baseline is deteriorating. Plus, you have these deviations that may be a result of policy shocks and political shocks. So then, I think that would be my way to think about my long-term position in that company. But maybe different people have different methodologies. But in terms of this sort of whether or not we can go back, I think Orval would know this very well because Orval went to China very early on.

And it is very important to remember that Chinese economic reforms in the late 70s and early 1980s started with what they called liberalization of ideas, liberalization of thought, right? So there was always a component of intellectual relaxation. Many people would view Chinese economy, Chinese reforms happening under autocracy.

That's all true. But within that autocracy, they had these intellectual movement. So for me, what's really interesting now is that you are beginning to hear pushbacks from liberal Chinese economists against what is going on now. I'm very interested in finding out what's going to happen to that pushback and critique, right?

Whether or not you tolerate that, once you tolerate that, it's only going to grow, right? And then the next decision you have is, are you gonna tolerate that? At some point that is going to be at a level that would be very difficult, more and more difficult to push back, right?

And that will gave me at least an indicator of how far they take the economic slowdown seriously. So far, they have not kind of come down on these critics. So I think that's a good sign. And although they have done other things that are really, really counterproductive from an economic perspective, I think we see kind of these mixed signals.

I think China is in a more interesting phase where they need to make some adjustments, but they don't really know how to do that. And it's happening right in front of our eyes. And we may see something interesting within a year or two.

>> Orville Schell: We're at time but I wanna give the questioners just very briefly an opportunity to pose their questions.

So let's just get them all in succession.

>> Speaker 10: This question may be unanswerable, but I was just reflecting on Xi Jinping's eternal friendship with Vladimir Putin and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Does anybody on the panel have any color on a possible invasion of Taiwan? What is the regime thing?

Would they ever do it? Thank you.

>> Speaker 11: Hello, this question follows Yajing's point about the party and the business relationship, how the business can influence the party and the party can influence the business. I'm just curious what the role of Hong Kong is in that both impacts to the West, but also Hong Kong is a note to influence policy in China.

>> Speaker 12: My question is, so recently I finished the book Deng Xiaoping by Ezra Vogel. And two of the four things that he identified for Deng's successors to focus on was, one, fight corruption, and two, improve the issue of inequality beyond economic growth for its own sake. So I was curious what the panelists think of Xi's track record on those two issues, which obviously might require a little more centralization or party strength to address.

Thanks.

>> Speaker 13: I'm interested in how China is using investment in other countries to build power, particularly Africa, Latin America, Middle East. And I'd like to ask the panel, to what extent do you think this is a risk, particularly since this C turn Matthew discussed, as Chinese companies are becoming more and more compliant with the Chinese state.

And cynically I ask how long before, at least more than half the population in these emerging countries are under the indirect control of China, either through the cooperation or through the government relations. Thank you.

>> Glenn Tiffert: So these are all very big questions. I'd invite you to offer capsule answers, or responses.

>> Orville Schell: Putin? Well, there are not too many other countries, of consequence that will buddy up with China at this point, except Russia. He stuck with Putin, Putin stuck with Xi, and that's a very difficult historical relationship. I'm not sure it's gonna end up well, but I think it had some rope still to play out.

>> Anne Stevenson-Young: Yeah, I mean, I guess the organizing principle of most of these questions is China's relationship with the world. And I think that that what we see in China right now is tremendous failure of the BRI program and antagonization of southeast Asian countries that first participated in it.

And then China's migration, increasing antagonism with the United States and with European countries, and China's therefore migration to building a new global south, much like the Nehru idea of the, what was it? Independent-

>> Orville Schell: Non-aligned-

>> Anne Stevenson-Young: Non-aligned, thank you. Non aligned movement, and I think that it's a move, a bit of desperation, and not one of strength.

The fact that dual circulation has been kind of dropped in the dialogue, and there's much more focus on the export economy is significant and suggests the weakness of the Chinese economy. And as for the support of companies like Alibaba going overseas, I don't really see that there's no interest in the party in having these companies acquire assets overseas, which is the nature of Alibaba and Tencent's participation in foreign markets.

Their actual commerce overseas is very, very small compared to China, and I think will remain so. As for their market value, we can go into that, but Alibaba splitting into six components, will they in total be still worth 200 billion? Very hard to say, but I think that the domestic sort of elite competition in politics and the stress we're seeing underneath the surface in China, or just barely underneath the surface, is going to be emerging into the international domain.

And probably the last thing is, my guess, is that the failure or really failure of Russia's invasion of Ukraine has been an important object lesson for China, and that there will be a lot more reluctance to have a blockade of Taiwan as a result. If China were kicked out of the swift system, for example, that would be absolutely devastating.

>> Yasheng Huang: I really agree with that, and I think sometimes history happens by a sequential order. So the Ukraine thing happened first, and then there are lessons that other countries have learned from that. And the other thing, I also agree with Anne Stephens' view of China's position in the global economy.

It is really important to always emphasize this point, how much China has benefited from the current, you can call it western whatever, economic, global order, right? So you want to challenge something that you have benefited from, I don't quite see the rationale for that. And the other is that the sort of pivoting toward Russia other than the personal relationship between Xi and Putin.

But just as an economic measure, the size of Russia economy is the size of Guangdong province. Guangdong is a powerful province, but it is a province- And $1.7 trillion. And whereas the West, US, Europe, Japan, South Korea, no, that's like $55 trillion. So there's the celebration that China is increasing trade with Russia by 50%, 60%.

But the decline of the trade share with the West, it just doesn't really equate with each other in terms of pure math, and it just simply does not make any economic sense. I think Deng Xiaoping saw this issue very, very clearly. He once said that for some reason, countries that are friends with the United States tend to do well.

The countries that are friends with so many intend not to do well. I don't think this is a terribly revolutionary claim because you can just look up the World bank data and get. But for a leader to have that insight is just incredible, right? So I often just want to point out these basic facts, right?

And how much Chinese economy has developed under this Pax Americana system, whereas its economy is stagnated under the Soviet system. These are just basic, basic facts, and we need to lay them out every time we speak about these issues before we get to the policy specifics.

>> Glenn Tiffert: Right, I wanna be mindful of time and thank our panelists, thank Matt, thank the Asia Society, a great deal for their partnership in the projects that we do.

And thank you all for coming and our audience online as well. I hope that if you still have questions or want to discuss, we'll be around for a few minutes, maybe having some coffee and can circulate. So that concludes the panel, and appreciate you coming.

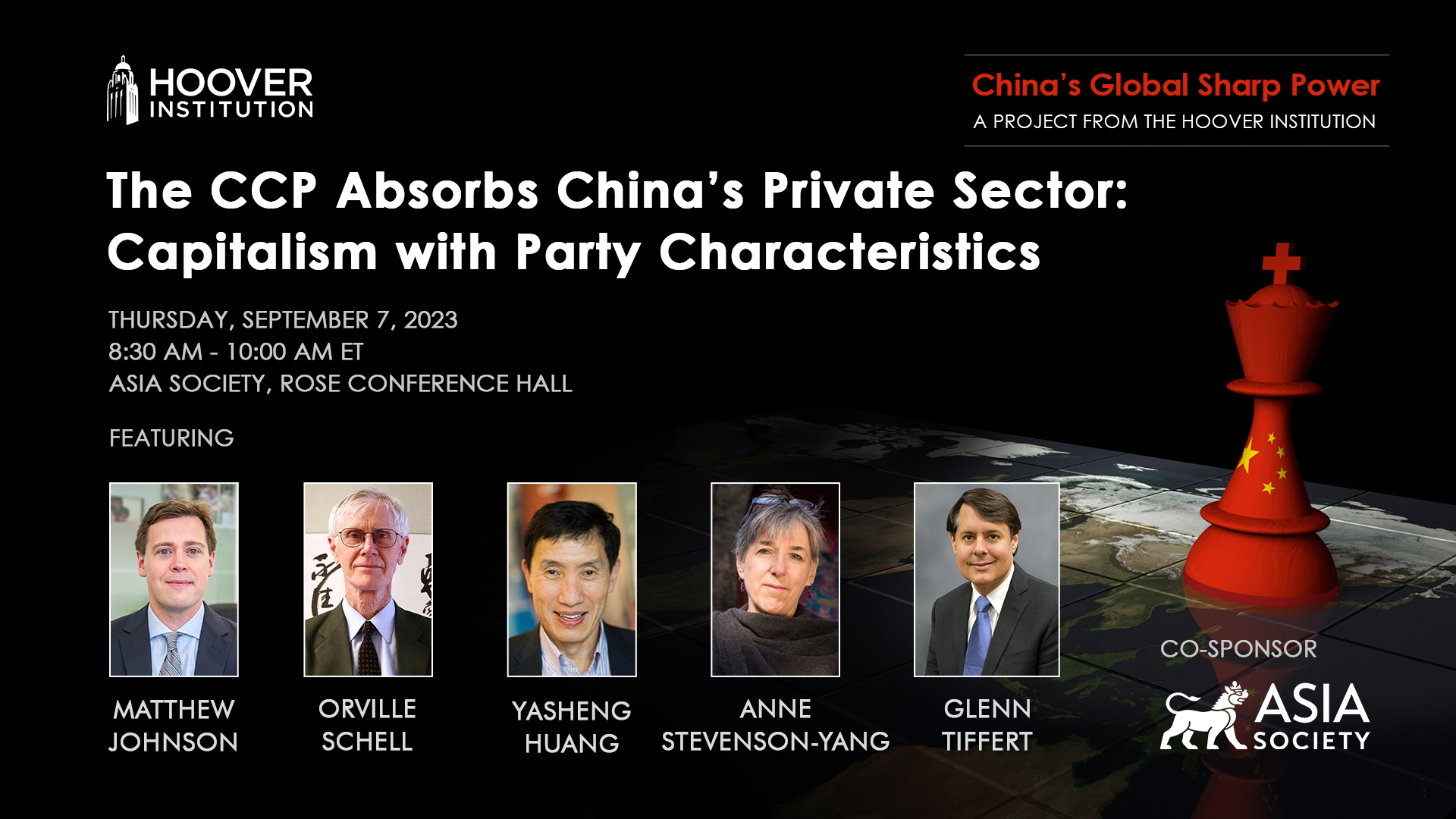

FEATURING

Matthew Johnson

Visiting Fellow

Hoover Institution

PANEL

Orville Schell

Arthur Ross Director

Center on U.S.-China Relations

Yasheng Huang

Epoch Foundation Professor of

International Management, MIT

Anne Stevenson-Yang

Managing Principal

J Capital Research

MODERATOR

Glenn Tiffert

Distinguished Research Fellow

Co-Chair, Project on China’s Global Sharp Power

Hoover Institution