The Hoover Institution hosted Women of Wargaming: From World War II to Today on Friday, March 14, 2025 at 9:00 am PT.

This panel delves into the women of wargaming from the wrens to today and tells the story of how women have shaped submarine tactics, US foreign policy, military campaigns, and nuclear warfare. Join us for expert insights from Hoover Director, Condoleezza Rice, moderated by WCSI director Jacquelyn Schneider, and featuring CNAS’ Stacie Pettyjohn, University of California Berkeley’s Bethany Goldblum, and Stanford’s own Emma Barrosa.

>> Presenter: In June 1940, Nazi Germany initiated what they called the Happy Time. Under Admiral Karl Donitz, German U boats hunted in wolf packs, devastating allied shipping. The Battle of the Atlantic was the longest continuous military campaign of World War II, with approximately 2,200 Allied merchant ships sunk in the Atlantic.

Each ship lost meant fewer supplies, weapons and food reaching Britain's shores. Churchill would later write that the U boat threat was the only thing that ever really frightened him during the war. In Liverpool, the Western Approaches Command established a unique unit known as the Western Approaches Tactical Unit, or WATU for short.

This unit, mainly comprised of young women from the women's Royal Navy Service, was tasked with wargaming new anti-submarine tactics. The unit would host Allied convoy commanders docked in Liverpool, training them through war games before they sailed into the Atlantic. Dedicated servicewomen like Jean Laidlaw and Janet Okell worked alongside Captain Gilbert Roberts to develop revolutionary new anti-submarine tactics in WATU.

Despite extensive literature on the unit's achievements, these servicewomen's tactical contributions remain largely unattributed, but they will be anonymous no longer. This panel delves into the women of wargaming from the Wrens to today, and tells the story of how women have shaped submarine tactics, US foreign policy, military campaigns, and even nuclear warfare.

Join us for expert insights from Hoover Director Condoleezza Rice, moderated by WCSI Director Jacquelyn Schneider, and featuring CNS's Stacey Pettyjohn, University of California Berkeley's Bethany Goldblum, and Stanford's own Emma Barrosa.

>> Condoleezza Rice: Good morning. So it's really an honor for me to be able to open this wonderful conference on women in war gaming.

It's both the women and the war gaming that I'm honored to be able to do. I just want to say that this subject matter is something that is of great interest to me, me for a number of reasons. I remember that the first time I really learned about war gaming at all was as a young student understanding how we came to think about strategic stability in the nuclear field.

Because when you think about it, the idea of weapons that were as destructive as nuclear weapons would lead you to wonder, is it even possible to think about stability under those circumstances? And because of a lot of work that was done at the RAND Corporation, in particular, Thomas Schelling and his team around, really, they were game theorists, and they did very interesting work on how to think about stability.

And out of that came nuclear doctrine, which ironically, we were even able to finally agree with the Soviet Union, our adversary, on what would constitute stability. And we continue to have in the nuclear era, new challenges in terms of stability, whether it is questions of rogue states, Iran, North Korea, or whether it's a question of what a new entrant into large scale nuclear weapons like China is going to mean to strategic stability.

I say that because the history of war gaming is something that we should understand as we look to the challenges of the future. It's also the case that I don't call it war gaming when I do it, but I teach with a lot of simulation. I do that because I find that my students, first of all, their attention span seems to be longer if they're doing simulation than if I'm just lecturing.

They get very into their characters. It's the first time that I don't have to say, just because you've googled it doesn't mean you've researched it. In fact, they will go into depth to understand before doing simulation. So wargaming simulation, the ability to use it to ask questions that might not ultimately occur to you were it not for the opportunity to go through a war game or through a simulation.

I'll tell you one final story and then I will introduce our panel, which is that nearing the end of the Cold War, there was something during the Cold War, there was something called continuity of government teams. And the idea here was that if the United States was attacked, there had to be some part of the US Government that survived.

Think that great show which was called Designated Survivor. Well, it's sort of like that. And I was actually a part of a Continuity of Government team. In the summer of 1989. I'd gone to work for George H.W Bush. In the winter of 1989, there was going to be a game simulation, a war game about a strike on the United States and the continuity of government team.

And we were going to be sent out to some remote part of beyond Washington, D.C. you don't ever get to know even where you're going. And I said to Brent Scowcroft, the national security Advisor at the time, I was the young Soviet specialist, I said, I don't have time.

I don't have time for this. Germany's unifying, Eastern Europe's liberating, Soviet Union's collapsing, I don't have time to go do a war game about nuclear weapons. And he said, well, I'm sorry, you're stuck because you are our representative to that Continuity of government team. And so I went out and interestingly, the chief of, I was chief of staff in the game to Don Rumsfeld, who was playing president in that game.

So we go through the game. I come back fast forward to a number of years later when I was National Security Advisor, and on an awful Tuesday morning, there was the attack on the United States, and we were all shuffled off to the bunker. It was really extraordinary, you know, your head spinning.

And two things that I had really come to terms with in that game back in 1989 came to me immediately. One was, you have to get in touch with Vladimir Putin, because we might get into a spiral of alerts if we are not careful. We alert, they alert, we alert, they alert, pretty soon, you're at DEFCON 1.

And as it turned out, Putin was trying to reach President Bush, who was trying to get to a safe location. And I talked to him And I said, Mr President, we are going up on alert. He said, yes, I know. I thought, of course you can see it.

What am I talking about? Of course, you know. But he said, we're canceling all exercises, you don't have to worry about a spiral of alerts. The other that came to me out of that experience in 1989 was when I said to Steve Hadley, the Deputy National Security Advisor, we have to get a message out to every post in the world that the United States of America has not been decapitated.

When you think about the pictures that day, they were all of the whole blown in the Pentagon, the World Trade Center Towers coming down. We couldn't speak, nobody was hearing from us. The President was trying to get to a safe location. We were in a bunker. And so it was important that both friend and foe know that we were not decapitated, that we were functioning.

That came directly out of that 1989 experience. And so my point is that that wargaming has a special place in decision making of helping you to identify. Identify and think about things that otherwise might not occur to you. And so it's an extremely important tool. And I'm very glad that Jackie Schneider, who is a Hoover Fellow, has brought it here to the Hoover Institution from her work at West Point, her work in the government, her work as a military officer.

And so, Jackie, I just want to say to you, thank you very much for leading these efforts. And then I want to thank Jackie for putting together during Women's History Month, this wonderful panel about women and war gaming. Not to say that women are particularly good at war gaming, but just look at this group.

Maybe so. So Stacy Pettigoan has led defense war games since her time at RAND and is now pioneering unclassified war games at CNAS, and is one of the thought leaders about the future of warfare and the impact of technology on US Force modernization and military campaigns. Bethany Goldblum is a nuclear scientist who led one of the largest war game collaborations between the Department of Energy and Academia.

She is building the next generation of nuclear talent for the American government and is using war games to help us understand the impact of tactical nuclear weapons on. On international stability. And Emma Barrosa was our first intern for the Hoover War Game and Crisis Simulation Initiative. And as a part of that position, she just threw herself into the archives in Liverpool, retracing the steps of the Wrens as they developed the submarine tactics that would define Britain's underwater strategy against Germany.

An extraordinary story of women and their role in war. So we're thrilled to highlight her research as well as her artwork, which I hope you'll get a chance to look at, which is really quite extraordinary. And so with that, let me turn it back to Jackie Schneider. Thank you all for coming.

I think it's going to be a very exciting set of discussions. And over to you. Thank you.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: Well, on that really wonderful introduction, I want to thank you all for braving the rain in California to come out to visit us here at the Hoover Institution. And I want to highlight on each of your tables, there's some postcards.

Those postcards are for you all to take, and they include Emma's original artwork inspired by the Wrens, as well as the submarine tactics that were devised by the Wren unit and that Emma discovered in the archives. So I want to start there from the past. So let's start the conversation from World War II and from the Wrens.

So can you tell us a little bit about who the Wrens were, what was happening in World War II, and then tell us about kind of these women. What were they doing in Liverpool at this time?

>> Emma Barrosa: Yeah. Hi, everyone. So the Western Approaches Tactical Unit was created to solve this really looming U boat crisis that Great Britain was facing in 1941 and 1942.

Six months into 1941, they had lost about 3 million tons of shipping, and that was a really significant number in 1940. They had lost 3 million tons of shipping in that entire year. And already six months into 1941, they had already lost that number. So losses were rapidly increasing.

1,300 merchant ships were sunk in 1941. And they needed solutions to fix this Yubo threat. And so Churchill and his officials got together and they decided to create this unit that would essentially war game out all of the old battle reports that they were receiving from the Atlantic and try to find new tactics to eliminate these German U boats.

And so they appoint Captain Gilbert Roberts, who was an esteemed naval officer and war gamer, who had extensive experience at former British tactical schools, to lead this unit. And they set shop up in Liverpool, which is a very important strategic position because Liverpool has this beautiful bay. I was there last spring, and it's perfect because convoy and escort commanders can dock in Liverpool War game for a couple days with this unit and then go out into the Atlantic and fight these U boats and protect themselves.

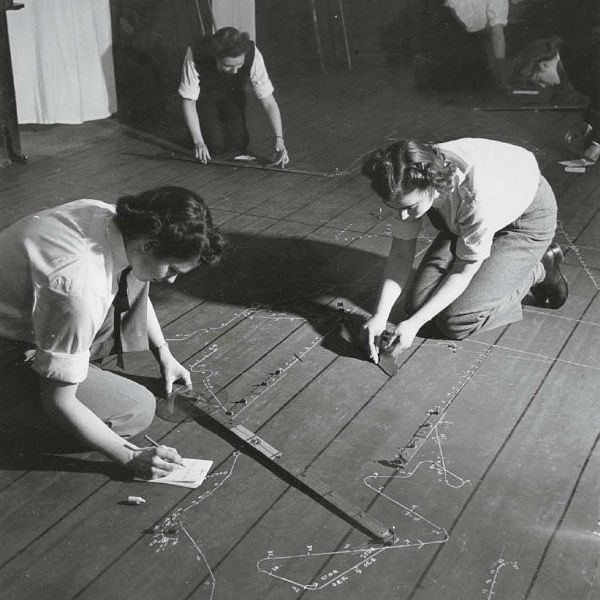

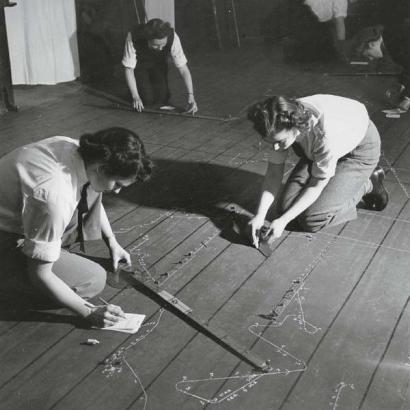

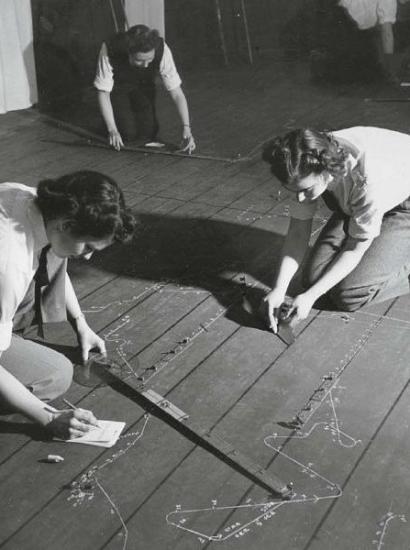

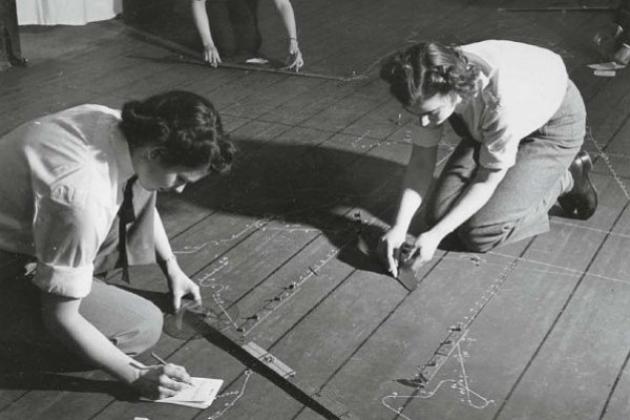

So they set up shop in Derby House, which is this medium sized brick building, and they would use the floors as. As their war game. So the floors were the map of the Atlantic. And as you can see in the photos from the video, all around the map, they had these booths where officers would peer through.

And it kind of simulated the visibility in the Atlantic. And you could see all these different tokens that represented the U boats, the convoys, chalk lines showed where they were going. And so it was this quite immersive experience. And they would alter it every time for weather conditions and new developments that they saw in former battles.

And so Captain Gilbert Roberts needed staffers, so he enlisted the help of women from the Women's Royal Navy Service to help administer, lead and take notes on a lot of these war games. And we see with a lot of the Wrens, they enter Watu, as it's known, mainly as administrators, mainly as note takers.

And so they're kind of like the secretaries behind this. But then I think what's super important, why I'm so obsessed with the Wrens is because they got so good at understanding the game, taking notes, being the statisticians, they knew the game better than anyone else. And they were the ones that recognized game patterns first.

And so you see people like Jean Laidlaw and Janet Okell coming up with these tactics before Roberts, because they were the math wizards is behind this game, the statisticians. I'll just share briefly about these two women because I feel like after studying them for a year, I've really started to identify with them.

Jean Laidlaw began her time in Watu at my age when she was 21. She was a certified statistician beforehand, an accountant, and was well known in her school years for being a math whiz. And later, she began to be known by Roberts in his diary as, quote, his number one throughout the entire war.

She's most well known for the raspberry tactic, which basically was this tactic where they would do triangular sweeps around areas that they cited U boats to try to pick up on sonar.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: And so some of you might have a raspberry tactic on your.

>> Emma Barrosa: Yeah, feel free to look-

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: On your postcards.

>> Emma Barrosa: And so she helped devise this with Roberts. And when the admiralty came in and asked him, you know, what's the name of this tactic? Who was the inventor? He deferred to Laidlaw and said, well, she did all the boring statistics. So she named it the Raspberry because she wanted to give a raspberry to Hitler.

And the last person I'll share about is Janet Okel, who also started out as a note taker and statistician, but became really good at administering war games and playing in war games. And so she was most well known for the beta search tactic, which some of you have.

And typically when tactics are about to be universalized for commanders to use in the Atlantic, they would first have to be played through by the admiralty. So one day an admiral comes in, Admiral Walker, and he doesn't quite believe in war games and is a little critical about this.

And here walks in Janet Okal, this very young girl about to play against him, and she is going to display to him how her beta search tactic can eliminate his U boat. And he has extensive knowledge from World War I about how U boat tactics work. So he says, you know, this is a done deal.

I don't think it works. And she beats him. She beats him multiple times, over and over again. And beta search starts to be used in mainstream escort defenses in the Battle of the Atlantic. And so you see these women emerge from note takers and statisticians to leaders in this unit.

And I think that's what's so beautiful about Watu and why I'm so excited about this research.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: So part of one of the reasons that I really love your research, Emma, is that it wasn't that women were in the war games to create peace. I think often if you're a woman in national security, you've been invited to a conference that's women, peace and security, right?

It's always peace and that's not really what they were there for. They were tactical, they were in the weeds. They understood how weapons worked, they understood how sonar worked, they understood the role of weather and these kind of very tactical variables. I think that that may not be what you would normally expect, right.

But Stacy, you come from a background where you've spent almost decades working hand in hand with the military in designing war games. You led the war gaming at rand, which, as Dr Rice mentioned, rand has been a leader in defense war gaming since the 1950s. Can you help us in the room?

Because not all, I'm not sure how familiar everyone is with the games. Can you first explain to us kind of how does the Defense Department approach war games? And then I'd love to hear more about your role and your pathway towards working in games.

>> Stacy Pettyjohn: Okay, well, there are many different games in the Defense Department, and they use them for a multitude of purposes, which are all entirely valid.

Sometimes, though, trying to achieve multiple objectives at the same time with one game can end up hindering them a little bit. So one of the first things that games do really well is help you to explore a problem that you might not have thought about. So it's like the what if situation.

I had colleagues at Rand that in the 90s the Cold War ended. They were like, what if Iraq invaded Kuwait and started thinking about that right before it happened. And in my time, because I'm not quite that old. Thanks, Jackie. The at Rand, after Russia's first invasion of Ukraine in 2014, when they seized Crimea and parts of the Donbas, folks at Rand began thinking about what if Russia attacked NATO?

What if they attacked the Baltic states? Could we defend them? We have a lot of confidence in NATO's conventional military superiority, in particular its air power. Is this something we're prepared to defend? And they discovered that, no, we're not prepared to defend a piece of territory that extends as far as the old intra German border with a handful of territorial defense units.

And that air power alone could not do it because you could not mass enough force quickly enough to actually stop a massive invasion. And this led to an entire effort within NATO and with the United States to adjust its defense posture. And to create what they called an enhanced forward presence with some battle groups in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.

So exploring a problem is one thing. One of the other really good uses of games is innovation. As Dr Rice mentioned, when you are there are things you just can't think of. And being in a very stimulating and immersive environment like a war game where you're facing a determined adversary that's really trying to beat you, it gets the creative juices flowing.

And you might think of things that you wouldn't have otherwise. They might be tactics, they might be larger operational concepts. It might be just blinding flashes of the obvious, but it's really hard to notice those unless you're actually looking at the problem from a particular angle. The next use is comparing and evaluating different operational concepts or tactics or strategies.

You can use it at all levels of warfare. So down at the tactical level, how do you actually find submarines and stop them from attacking your ships? But broader concepts like how would you defend Taiwan if China were to attack it? And this is one of those problems where the Department of Defense has long realized it would be very challenging given the geography of that situation.

And they've invested a lot of resources in trying out different concepts and different strategies to defend Taiwan and sometimes imagining new technologies and capabilities that they don't have. But wish that they did, or wish that they existed and seeing if that would help them win. And the final purpose of games is to sort of socialize these ideas or help educate people, train them.

And that is often a really important use of games for senior leaders. Their time is very, very stressed and limited. And they can take away lessons and often will do so in a way that is much they'll be. It'll leave a much stronger impression on them to have participated in a game than them to be briefed and to be told what the answer is.

And so games are often used in the department to validate concepts. Which is my least favorite way of doing it. Really you shouldn't use the same game to do all of the same things at the same time. The department has evolved and run many games that you always hear about the interwar years and what the Naval War College did, which was great in developing Warplay in Orange.

But with the modern operational concept that the department is thinking they'll use multi domain operations. That began with a concept which was entirely made up with technologies that don't exist. Have sort of refined that over time and built the tactical foundations that they need to have this broader strategy and to determine what sort of forces they want to purchase, what mix, what numbers.

One of the challenges though is that games don't provide you with a precise answer. At a certain point you need to go and do some hard operational analysis. Use actual numbers, models and simulations that you can run thousands of times, not just a few dozen, like a game.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: So one of the things I would really love you to help explain people because I actually get this question all the time. I get two questions. One is what is a war game? Which we'll come back to at the very end. But the second is how do war games occur?

So let's say you're working at rand. Do you come up with a good idea and you're like, let's run the war game. How do you guys decide how war games happen?

>> Stacy Pettyjohn: Oftentimes, it's the government, they sponsor it, right? They want a war game for a purpose. All of the services have their big war games that they run annually to continue to rehearse concepts and test them, educate.

It's unclear sometimes what the purpose is, but at rand, there are games that are sponsored. At CNES, there are games that are sponsored by the government, but sometimes we just do things on our own with sort of discretionary funds. The Baltics game was an example of that no one had sponsored.

And Imran was like, I think this is a problem we should think about. And at CNES, we similarly sometimes run games. I just ran one last week looking at how to counter drones in the context of a big war with China that wasn't sponsored. It's just part of my research that I'm doing and that I thought, what was the answer?

There's no-

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: By report.

>> Stacy Pettyjohn: Yeah, there's no easy answer to that problem. You really need a lot of different layered defenses. But I suspect what we postulated was that if you were to engage, if we were to get into a war with China, which we don't wanna have happen, it would be protracted.

And you would see them relying on cheap drones like Russia has over time as their inventories of more expensive and capable missiles were exhausted. And that could be a really severe challenge harassing Marines in the Southern Ryukus or Air Force aircraft in the Philippines trying to conduct dispersed operations.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: I think one of the themes that we get from both Stacy and Emma is that war games are often used to help us understand technology and the integration of emerging technology in campaigns. Bethany, you're a nuclear scientist and you led a game, the signal war game, which was one of the largest iteration war games that I know about, and it was a remarkable collaboration between the Department of Energy and partners in academia.

And that's a little bit of a different process than the Department of Defense kind of asking for a game, or even me as an academic saying I want to run a game and deciding my question and designing. Can you walk us through a little bit about what the signal game was, what you were trying to accomplish and how that works?

You collaborate between the Department of Energy and other kind of non-governmental organizations.

>> Bethany Goldblum: Yes. So signal stands for strategic interaction Game between nuclear armed lands. And it was put together as a project between UC Berkeley, Sandia National Laboratories, and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. And so we were looking at the question of how do tailored nuclear weapons impact the likelihood of nuclear use and specifically looking at high precision, low yield weapons and EMP tailored devices.

And so there it was more of a research project. So the collaboration was really natural, actually. We had folks from the laboratories come to the university environment and we would just spend days together locked in a room, developing the game and playing out different scenarios we were specifically looking at.

So where we landed was three different countries, two of which had nuclear weapons capabilities. And then, we wanted to execute this as an experimental environment. So we had a control scenario and then a treatment scenario. So in the control scenario they just had traditional high yield nuclear weapons.

And then in the treatment scenario they had these high yield nuclear weapons and the tailored weapons, the high precision, low yield weapons. And so then we ran the game many different times in multiple formats. So we had a board game that was developed, which we still have copies of in the office, and a video game, and with three alive players through the duration of each of those games.

We collected the data and then we looked at what was the difference in behavior in those two different scenarios across many, many different types of players, from students to military professionals. And ultimately we found that in the game environment there was no statistically significant difference in the likelihood of nuclear use with high precision, low yield weapons in the arsenal.

And this was really interesting at the time because there was this big debate about introduction of the W76 mod 2 warhead, which had been called out in the nuclear Posture review. And so there was a lot of debate. Is this going to, because it is a low yield variant, is it going to be more likely to be used?

Or because it is a low yield variant, is it going to strengthen our deterrent threat? Because it would be more credible that we would retaliate with this weapon as opposed to completely decimating cities in response to a nuclear attack. But ultimately there was no way to adjudicate that because that's not an experiment we want to run in real life.

And so having this in the game was a way in which we could explore this question quantitatively, systematically.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: I think it's important to understand the context behind when these games are occurring. So as you guys are running the signal game, which, how many, how long was the actual running of the game and how many players?

>> Bethany Goldblum: So it was years, because well, so we held a number of different gaming events where we brought professionals together to play the game, and particularly in the board game environment. But then we launched the video game and collected data over years and we had online gaming events as well, but there were many times just players randomly joining the game over this period of time.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: So estimate how many players.

>> Bethany Goldblum: We had more than 400 players, which.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: Is a really high number. And the fact that this was occurring over a long period of time. But everything Bethany said kind of shows what a scientist she had. She has control, she has treatments.

She's thinking very carefully, carefully about the design of the game. So at the same time that she's running, what is a really unbiased question. Like, you don't have a stake in what they choose, right? Like, you're not going into it and you're saying, hey, I really want to show that tactical nuclear weapons are the right choice.

You're just a nuclear scientist, like, I wouldn't say ambivalent, but you don't have an answer that you're trying to find. But at the same time that she's doing great science, and the Department of Defense is actively debating about whether or not to integrate tactical nuclear warheads into their inventory.

And this comes to a head at the end of the first Trump administration. So there was really significant lobbying that was occurring within the Pentagon and within Congress to reinvigorate this tactical nuclear weapon capability. And it had actually come up as part of the nuclear posture review done at the beginning of that administration.

But they had lost the election, and they didn't know they were coming back. And so they were concerned that their lobbying for this weapons system, which was going to take a while to develop, would be cut as soon as the Biden administration came in. So at the end of the administration, Strategic Command ran a war game as Strategic Command, which featured the secretary, the current Secretary of Defense.

Esper. Let me tell you, we almost never have sitting secretaries of defense play in war games for one, one reason because it takes a lot of time. But the second is you generally don't want the Secretary of Defense playing for kind of political reasons. But he played. Another big thing that happened they announced it.

Strategic Command told everybody that they ran a tactical nuclear game. And they said they ran a tactical nuclear game against Russia. That never happens. And then they said, and it showed that we need tactical nuclear weapons. And that also never, you know, we never tell people those kind of things.

So it was really interesting that at the same time that, you know, you're playing this kind of unbiased game to answer the scholarly question, you have a major war game that's occurring within the Department of Defense that is, you know, potentially kind of developed in a way, or at least announced in a way that's meant to influence a larger policy debate.

So, so it's really interesting the way in which these games fit within these different communities, within academia, within the Department of Defense, within the kind of think tanks and the FFRDCs. And so I think that makes me wanna ask this follow-on question, Bethany, which is, you're a nuclear scientist, you're teaching and researching within academia.

You gave us a really good example of a way in which academia can sit on a problem for a long time and try and answer it in the most unbiased way you can. But how do you think more broadly about using war games in academia? What are the good questions?

And then where do you see, you know, I'm a political scientist, a fuzzy scientist. You're a hard scientist. Do you see these kind of games being used more and more often in hard sciences?

>> Bethany Goldblum: So it's interesting, as Stacy was talking about, the way that the games are used in DoD, I feel like that that's true in academia as well.

We definitely use war games, or sometimes referred to as simulations, as Dr. Rice said, just for training the students to get to grasp different concepts or to explore a topic. So what are scenarios that might come up when confronted with a new operation or the things that you maybe wouldn't have thought of if you were just thinking through the problem.

And then from, I'm really excited about the experimental aspect of it. So one of the things that came out of the signal game I mentioned that we found at least in the board and online game environment, that there was no difference in the likelihood of use with these tailored effects weapons in the arsenal.

But we also ran a survey experiment and this is a more traditional approach that social scientists use to answer these types of questions. It cost a lot less than developing a war game and there, there was an increased likelihood of use with these tailored effects weapons in the arsenal.

And so I think that that calls into question what are the differences in these two environments. I mean, one that we know is different is that war games create a more immersive experience where the participant could have some buy in into the situation that they feel that there's some responsibility for their actions that may be less so if they're just filling out a form on a survey.

And so from an academic perspective, that's really interesting in that how do these different data generating processes lead to different results and then what are the implications of that for the findings that are coming out of these different platforms?

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: I think one of the things you just brought up there, you talked about bias.

I think one of the other really big debates in war gaming is whether who plays the game matters. So you had 400 plus players. Some of those players are probably like true experts and some are probably students. I've run a game that had almost 600 players and some were heads of state and others were local leaders who ran bakeries.

So you had a really wide array of expertise and sometimes in the games that really matters and sometimes it kind of doesn't. So I'd love to hear and both Bethany and Stacy, cuz Stacy, your games are generally run with like true experts, right? They're the military officers, the decision makers that are playing the games and I know there was a really good back and forth in was it science about the role of expertise in the gaming sample.

So I'd love to hear both of you, kind of your perspective on who's the right war gamer. How does the different players affect the outcomes of the games?

>> Bethany Goldblum: So I'll start. So we looked at this experimentally in that for the online game environment, we collected demographics on the players and so then we could ask questions about how does the conclusion change if the player is female or if the player has experience working in a national security environment.

And we had people from StratCom and undergraduate students and everyone in between playing our game. And so we didn't have enough statistics, I would say, to be able to adjudicate whether or not there were differences or within the data set that we had, there were no statistically significant differences that we observed between those with experience and working in the national security field and those that did not.

But I think that this is a very interesting study as well in terms of what is the potential bias introduced by different types of players and then what player set do we need to be able to inform questions that are of national security importance? So I'd be interested to hear Stacy's take.

>> Stacy Pettyjohn: No, I mean, I agree. I think it's an empirical question that can be studied and answered. My position has always been you need to have players. You either need to have a game or you need expert players or a game that is designed where non experts can make smart decisions.

So if they aren't making informed decisions, you're not learning anything. If I'm running, if I were trying to design tactics for, you know, convoy operations to avoid submarines, I'm not a submariner. I don't know how to do that. I would come up with some dumb ideas and they would probably fail.

You should not take much from that other than I don't know much about submarine tactics. If I want someone to do that, I want people who understand, who study it. They might not actually be the operators themselves. Oftentimes operators have very narrow expertise that's very, very deep, but they don't understand the broader implications.

And a lot of the games that I run are operational level, where you're looking at a theater. Like what would happen if North Korea attacks South Korea across all the different services. And you need to bring people together. And that's one of the things that games do well, where you can integrate this really detailed, complex knowledge and mental models that people have.

And then you have adjudicators who either are running operational models to determine the combat outcomes or who can make assessments in real time, bringing through a conversation. So my view on players is that they need to be able to make informed decisions in the game for what you take away from it to be valid.

And that can mean many different things. Some former, well, current and former colleagues of mine, we ran a war game for Girl Security a number of years ago. Now, that was actually a Korean War scenario. And we designed the game in a way that non experts could come in and play.

And I would characterize it not as a game for women, but as an introductory operational game. And frankly, the game I ran for members of Congress looked a lot like that because they also are not military experts. But we set up the game, we constrained their choices, and that meant there was more sort of bias, less freedom of action, because they had force packages and choices of actions that they could take instead of just being able to construct whatever sort of strategy or operations that they wanted.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: So you mentioned, Bethany, different demographics of your players. So we have. Difference in expertise is one kind of way in which you can look at different demographics. But one of the big demographic differences is gender. And ostensibly this is a panel about women of wargaming, but it is really unclear to me sometimes both as someone who designs games, plays in games, and then also who analyzes data whether women actually play games differently than men.

And I'd love to hear the panel. Emma, There's a bit of a counterfactual, right? Like, did it matter that these were women that were doing the submarine tactics? Would have been different if they were men. And then, Stacy, in your experience playing war games, designing war games, analyzing war games, is there something fundamentally different about when women are involved in either the game design or the game playing?

And then, Bethany, from your data, is there. Is there a data difference between women and men when we play in war games?

>> Emma Barrosa: Great question. So I would say just from my historical, historical research, it's less about gender and more about the role in which they were placed initially.

So these women were not the officers in the booths. From their individual perspective as U boat commander, they were the ones logging the data, they were the ones running it. And so they were in the position where they were looking at this game and this scenario from a very like meta level, they saw everything happening and so they can make larger, more operational game time analyses than these men who were in the position as just a Yubo commander.

And we see this a lot in a lot of the war games that I've looked at with hoover from the 50s and 60s and 70s where women were in this kind of note taking role. And so, yes, it's gender because all of the note takers in war games back then were women.

But I would say that role really helped women evolve in war games as the tactical leaders coming up with these tactics because they were looking at it from a larger perspective than a lot of these people that were playing in it.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: And I'll say I have been a note taker in a war game and it is remarkable how much perspective you get in the note taking.

Another kind of vignette about note taking. That big war game that I ran with lots of people, we actually did look at the differences in genders. And one of the interesting things we looked at was what role women were selected for or chose themselves for in the game.

So you could be like the head of state, you could be the secretary of state, the defense minister, economic advisor, intel advisor. And we were really shocked because I went back and looked at the data and when women played in the game, they were more likely to be picked as president.

And I thought, my God, like, wow, wow, this is the world we're living in. And I had this lovely RA and she's like, Jackie, that's not what's going on. What are you talking about? I'm looking at this, the feminist revolution. They said, no, no, no, no, no, whoever's the president has to fill out the response form so they give it to the women.

And I actually saw it one day. I saw a group, and it was a group of people who are pretty comparable in experience level, regardless of gender, very similar experience level. And they turned to the woman and they said, you fill out the response form, your handwriting's the best.

And she looked at them and she said, I have horrible handwriting. Why would you assume I have good handwriting? So just a vignette about kind of how funny the note taking there is, the strong relationship, Stacy.

>> Stacy Pettyjohn: I don't know if women play differently. Honestly, my sample size is probably pretty small.

Despite having run a lot of war games, the number of women who participate, despite my efforts to try to bring as diverse of qualified players in, has not been huge. I have not noticed a Huge difference. And where I think there can be challenges is empowering women where they feel comfortable enough to talk about military operations and tactics, particularly if they aren't actually serving themselves.

And a lot of men play soldier, play war games as a kid, they're like my dad, they have boxes of stuff, they're little fanboy soldiers. And that provides them with some fundamental knowledge and understanding of certain weapon systems and things. And I think that knowledge and that confidence is a bit of a barrier and that women can come up with as good of ideas, if not better ideas and do that.

They just have to be sort of sufficiently confident of their abilities in a group setting that's probably going to be male dominated for a while.

>> Bethany Goldblum: So I can, I don't have an extensive data set on this, but so I can say what we saw in our game environment and maybe just, just giving you a little bit more of a sense of how that played out too.

So the players could interact through military, economic and diplomatic means. And so, the reason it was called signals, because they would use a signaling token then to show on the map where they were gonna take an action. And that would give the other players then a chance to respond or to counter before the action actually followed through.

And so, in the case of this primary question of does it change the likelihood of nuclear use with high precision low yield weapons in the arsenal. There was no difference that was observed between men and women. But there was an increased likelihood that women would substitute these low yield variants for the high-yield weapons.

And interestingly those who self reported that they had more knowledge, higher knowledge about national security issues. And so this wasn't about their particular job, this was just, just did they think they were an expert in this area? Those folks also were more likely to substitute the low yield weapons for the high yield ones.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: So I've also looked a little bit at the data here about women in my games and no statistical difference between how women and men play in the games. My games usually are in a group dynamic. And so you go, okay, well maybe it's because women are kind of.

They're generally the minority in the group. But I actually ran one iteration at CSIS where I divided the group solely based on gender. So it was a woman only table, men only table, and then women and men. And once again, we didn't get a significant difference in the outcome.

So I went back in the survey data and we asked a question about, did you disagree with the group? Would you have played differently if you were by yourself? And I thought, okay, if women feel like they're being talked over, if women feel like they would have done something differently and this is where we would find it.

I didn't find that, but I did find that there were actually a lot of men who felt like they had not been listened to in the game. And when we asked them kind of what did you wanna do that the group wouldn't let you do? We had a lot of men who wanted to be more aggressive or to use, and these games are right on the edge of nuclear war were wanting to use nuclear weapons, but the group had talked them down.

So it was really interesting to me that there were assumptions about the way in which gender affected that dynamic, but the data didn't actually support those dynamics at all. So just since we're on a women and war gaming panel, I thought it would be kind of interesting to note those potential differences.

So I want to move back into kind of real life and the applicability of games for today's questions. So, Stacey, you had a game that was on the Taiwan crisis. One iteration was showcased actually on Meet the Press with sitting congressman. And then you took a similar game, I think into Congress and played it in Congress.

So I'm really interested in how you think, first off, what did your war games reveal about a potential conflict in which the US Is defending Taiwan? And then what role are games playing in influencing these policy traces about Taiwan and the US-China relationship?

>> Stacy Pettyjohn: Sure. As we had mentioned previously, you know, war games are this immersive experience.

So it can be really useful communication tool and help people to understand really complicated problems that are hard to sometimes impress upon them otherwise. The Meet the Press game was an interesting experience where NBC came to us and asked us to run a war game, said that Chuck Todd had wanted to do it forever.

And I was like, this sounds like a lot of work. And my boss was like, this sounds great, you should do it. And I did it. But it was a live play game that we hadn't scripted where they film for six hours and whittle it down to half an hour.

And it was interesting because we had approached that initially as an educational opportunity where, you know, we'd bring in expert players. We had Chinese military experts playing on the red team. We had like Michelle Flournoy and Mike Holmes, who's a retired four star Air Force general and some members of Congress who both had military experience as well playing on the blue team.

And that this could help to explain to the public some of the challenges of a war over Taiwan. Because you stand back and you look at it and it's like, well, China doesn't have as many aircraft carriers as us. Their tech isn't nearly as good though. That seems to be changing.

And why can't we win, right? Like, why shouldn't the United States be able to really easily defend a partner in this situation and stop aggression? And a lot of it has to do with the geography and then the capabilities and asymmetric strategy that China has kind of developed and plans would, or its doctrine says it would plan to use to negate some of those American advantages.

And when we played the game, we actually learned something because it happened not long after Russia invaded Ukraine and Putin engaged in all of his saber rattling. And there was people did things that I didn't expect in terms of using nuclear weapons and sort of walking through that.

So I felt like it was actually something where we, we went from it, assuming it was just going to be educational that we had qualified good players. But we learned something new. And the reason I didn't figure we'd learn something new is we were doing it quickly. We were gonna run through some of the stuff, the conventional fight, we've run, we've modeled a ton.

And then games, as they often do, surprise you. The game for Congress was a little different. We did that in two and a half hours. So it was really compressed and there were limited choices. It was not free play. Like we had menus of options for the players and we brought in former senior officials to role play different positions to sort of explain to them some of the major trade offs since they weren't military experts.

But that's also realistic in the real world. You know, the President is not an expert on these things. He or she would rely on the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. And they made their choices and went through it. We have learned that defending Taiwan is really hard and that we don't have enough munitions, probably not enough submarines, not enough bombers.

And. But that's making a lot of assumptions about China's capabilities and ability to implement really complicated operations, which would also be difficult for it. And right now we sort of assess that things would end up in some sort of a stalemate where the Chinese would get some forces ashore but couldn't actually subjugate the island entirely.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: So that game, it was interesting as somebody watching from the outside because there were definitely some congressional players who had like pre written statements about what they were going to learn from the game.

>> Stacy Pettyjohn: That never happens in a war game in the department. This is one of the different things.

That game was certainly an educational experience for members of Congress, but we had a representative from Virginia who was very much like, look at the importance of submarines and we need more torpedoes and things that were clearly driven by some of their parochial interests. But also, I mean, it is something that they probably knew more about because of that, trying to be generous and give the benefit of the doubt.

But normally when I, when we run games like these were educational tools, at least that's how we approach them for analysis. We have hypotheses about what we expect to happen, but we don't actually know and we don't, you know, validate something that we already know is the answer.

We, we are open to being proven wrong. And. But yeah, I'm sure members of Congress had their own agenda coming in.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: That brings up an important point which is, when players sit down to play a game, they have some assumption about whether what they're saying is going to be public or not, right?

In this case, you have some players who are very much controlling some of their statements afterwards. But we also have Jacob, our program manager, sitting back there. We've been bringing in games from the 1990s, 1950s, the 1960s. And some of them, you get transcripts of what people said, like LeMay says, we're gonna bomb North Vietnam back into the Stone Age.

I actually don't think LeMay would have been too upset that that got recorded. But other people might not be as candid if they know that they're going to be recorded, if their words are going to end up in our archive. And I think that brings me back to Bethany's work because this idea of a tactical nuclear weapon, it really skirts on a norm about what is appropriate.

And a lot of the pushback that you guys got about your research where people who were just aghast that you would test the use of nuclear weapons, that felt like such a taboo. And so the interesting question is, are people, are people behaving in the game? Are they speaking in the game the way they would normally if they, if they think that, you know, they're being recorded?

And actually, Emma, if you don't mind, I'd love to hear. Emma is doing her honors thesis using the signal game, looking to see whether. Telling people that they're going to get attributed and published, whether that changes the way they play the game. I'd love to hear if you have some initial data.

I didn't warn you I was going to do that.

>> Emma Barrosa: Sorry, I would love to share initial data. Do you want to go first or should I? Yeah, so I was actually for my honors thesis this year looking at this exact issue, and I used the signal game, the computerized version to test this.

And so I imposed two treatments among 18 different groups. The first treatment was this classified war game environment. Nothing would get out, and participants knew this. And then the second treatment was a completely public treatment, very similar to like an ABC News televised recording. So participants knew they were being recorded.

I had a camera and then I looked at the data to see if there were any differences in terms of tactical weapons use. And there was no difference. But what I really found interesting was that although there was no difference, data and statistics wise, the language they used was very different.

I noticed that in the private environment, participants were more willing to kind of just outwardly bomb someone without warning them, they were less cooperative. Whereas in the public environment there was a bit more cooperation that I saw. Now this is an N equals 18. This is a very small sample size.

But I think it's interesting to think about looking at war game analysis both in terms of what were the choices in made, but then also how was the language in which they made those choices used. So that's just an initial part of my thesis, but more to come in May.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: Stacy, have you ever noticed that people? Because you've run unclassified, you've run classified, you've run things that people know are going to really matter for a policy choice and things that are going to be one of the many war games that are used in a lot of policy choices.

Do you notice different behaviors based on kind of motivations or whether they're going to be recorded?

>> Stacy Pettyjohn: It's normally the scale of the game and the consequence of it. This is where I think there's a difference between what I do at CNAS or what RAND does and what the services or the department often does, where the games are very performative and they're very large, they involve hundreds, if not thousands of people.

People at times. And in some ways, they're more of a rehearsal where they're like, going through what they would do in this situation were to occur, which is useful. You can think through. If there's a crisis, continuity of government, we do this thing, we call this person. This is how we respond and actually do so in a timely fashion.

But it also is because of the stakes of those games where there are different programs up or concepts and they want something to be validated. And I always joke that one of the games that I led that was classified, there was a professional red team that was playing.

And most of you won't understand this, but I called them the Washington Generals. So if you know who the Harlem Globetrotters are, they had an opponent that they faced again and again, but they never got to win. But they had to make it look like a good game.

Right? And this is what this red team did. And it drove me nuts, because when I run a game and I choose the Red Team, I want them to want to win at all costs, to be cutthroat, to be very cunning, and to typically understand, you know, what their adversary's capabilities are.

And having sort of a patsey was really bad. So sometimes I do think I prefer games that are small. And I think the challenge as a game designer is to make the experience immersive enough that people forget that you're paying attention to what they're doing and what they're saying, that they're caring about what's going on and they're making the decisions and discussing why they might want to do something or why they might not.

Because that's where a lot of the really, the insights come from. And making them conscious that they're being observed can be a trade off.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: Bethany, on that, your game was both board game and computer game. And I often hear the critique of games is are you really collecting how people would behave in real life?

Or are you collecting the way they behave in a game if they think they're playing a computer game or they're going to act differently? So how do you answer that question?

>> Bethany Goldblum: So I can't say quantitatively the answer to that, I just haven't done the analysis. But I definitely feel that anecdotally there were differences in how people played in terms of their perception of their adversaries.

So if there was a group of students, then you could see them behaving perhaps differently than more having a good time or less worried about what someone might think about their actions or ha, ha ha, I'll nuke you, as opposed to professionals who were really trying to take it seriously and think about what would they do in a real wartime environment.

And so it was just a different tone. But I think that that would be a really interesting study and I look forward to see the outcome of Emma's work as well.

>> Stacy Pettyjohn: Can I add one more thing about being observed in nuclear weapons that I forgot to mention earlier?

In general, the nuclear taboo for Americans I think, is very strong. It's hard to get anyone to use a nuclear weapon in a war game. And if you want to explore in a game not because you want this to happen, but to deter it that a nuclear weapon would be used, you almost always have to script it.

Red teams, whether they're playing Russia, China, sometimes the North Korean experts are a little bit more willing to be crazy. We would never use a nuclear weapon. We would never do that. Which is why it shocked me in the Meet the Press game that some of the experts on the China team decided to use a nuclear weapon.

But it is one of those things that it's hard to predict why someone or when someone will do that. And that isn't actually what you should take always from games, but to understand the implications if they did. How do you manage escalation here? Why might they use it?

What are the benefits, the costs, the risks? And that's sort of what we've done with a series of games that I've run looking at China, and how their growing nuclear capabilities and tactical nuclear weapons could potentially be used.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: Okay, I'm going to do one last question, and then I promise I'll stop, and we'll open up to the room, and I'm going to come back to the women.

I want to hear from all of you. Emma from kind of the historical research, and Stacy and Bethany, from your experience, do women face a different standard in war games? And I think I'm really interested. I know some of your research looked into what role do stereotypes about women, and what role they're supposed to play affect, Kind of how women are included in war games, historically or today.

>> Emma Barrosa: Yeah, so I'll just share a brief example that I found in the archives last year. Not related to the Wrens, actually related to Lincoln Bloomfield's MIT archives. So, he held in 1968 a series of war games. One of them was called the Convex Games, and I found in that collection about a 20-page photo album of the war game.

And each photo had a caption, and two of those pages had women pictured in the war game. And there was one image of these two women scribbling furiously behind the war gaming table, I'm sure taking notes of what was going on. And I thought it was like a pretty normal image of two women being the note takers.

But the caption said, see, one hamburger rare, one hamburger not. And so, it was very obviously trying to trivialize their role as the secretaries, the people taking orders for food and coffee. And I think historically speaking, that's long been the stereotype of women in war gaming as the secretaries.

And it's so exciting to see now women as game designers, women as the administrators. And I think I'm so obsessed with what because that wasn't the case. Captain Gilbert Roberts, and these women, really took on a leadership role and were creating tactics and teaching these officers how to defend themselves in the Atlantic.

And so, that's why I'm so proud of this project in particular.

>> Stacy Pettyjohn: Yes, clearly there are different expectations and standards. And I know at rand, a lot of colleagues who were sort of junior to me and sort of middle analysts felt like they got stuck with the event planning aspect of wargaming because there's a lot of sort of moving pieces.

There's a logistical and administrative aspect to it which is by no means trivial, like actually having the game run smoothly, getting the right people there, inviting them requires you to figure out who they are, do all of this and, you know, people have different responses. When we ran the game for girl security, which they featured it on in an NPR story, there was so much hateful response about militarizing women and things that was thrown at us on social media and thrown at the Lauren Buddha who runs girl security, which I think is just nonsense.

If you want to be in national security more broadly in the United States, you need to understand all of the tools, diplomatic, military, at your disposal, what they can do, what they can't do. Have some basic, you know, knowledge so that you can question experts, even if you're not looking to be using them offensively.

You need to understand their strengths and weaknesses and limitations. So, yeah.

>> Bethany Goldblum: So, in the academic environment, I'll say no. I feel like that there's been many women that have engaged like in particular in the development of our game. There were men and women working hand in hand to do this work in the play tests that we did, students from across many different departments in campus.

So, I was the only nuclear physicist. There were people from the social sciences, there were mathematicians, there were game developers. And then I think there was a similar kind of diversity that you saw in the groups that were coming to play the game. And even now there's a lot of work going on at the Berkeley Risk and Security Lab, which is a center on the UC Berkeley campus led by Andrew Reddy, that you see students from all different departments, and both men and women coming together to work on these national security issues and war gaming.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: All right, and on that note, I want to open it up to questions, so feel free to just raise your hand, and we'll get a microphone to you. But let's make sure we get it on a microphone so that it can be recorded.

>> Hale Mori: Thank you so much, my name is Hale Mori, and I am a member of the community.

For me it was interesting that when you compare women, and men in wargaming is not so much difference. Since I have seen a document at Nova Science 10, 15 years ago, a six hours program that is very comprehensive about differences between sexes from different universities all over the world that they put compare women, and men from the stages of womb being in the womb to one day and until 70 years old.

And through six hours of that Nova Science it was very clear for me become very clear that women were smarter and made much better choices in general even from like first day to the seventh years. And I was expecting something like that. But then, when I see that it's not happening like that.

I am wondering, is it because of the expectation of society, and the treatment of women by the society impacting negatively on women in this situation, or is it men are stronger because of that? They have practice more the work as a child, or combination?

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: I do want to caveat that while Bethany may be the only hard scientist, none of us are actual scientists in gender differences.

I think we can speak only of our own experience, whether it's historical research or through games. I will say I think there's a level of selection effect for the women who are participating in my games because I do have a lot less women that choose to participate in my games.

And so, the women that do participate are ones that are very interested in national security. I always have to advertise something about what the game is they select into playing in that game. So then, what you're getting is you're getting a group of people that have chosen to give half their day or a full day because they're very interested in the question I'm asking about the role of technology and international security.

And so even though there are kind of these demographic differences between my players, like gender, they're coming at it from a shared similarity in that they think that this is relevant and interesting. And so that interest and that experience, I think is more of a determinant into how they play than any gender difference.

But love to hear everyone's perspective.

>> Emma Barrosa: Yeah, I think the points of entry for the rens were as the note takers and as the administrators. So, because of Britain's war machine at the time, there were select roles for women. And so those were just the points of entry at the time imposed upon because of the war.

>> Stacy Pettyjohn: I think I'd agree with Jackie's characterization. I haven't noted distinct differences in terms of how they play or the quality of the decisions that they make in most of the games. Almost all the games I run are groups, so there's a mixed group of individuals that end up having to make a decision.

And one of the things we always say in games is it's not the, the path not taken is often the interesting one. It's sort of the discussion that they have, how they weigh their options and where they end up, where they are more than what they actually decide to do, because you're only exploring one specific hypothetical future world.

So I think that there is a selection bias. And in general, the women players that I've worked with or the women game designers are as good, if not better than the men.

>> Bethany Goldblum: So one thing I can say is that in the case of the electronic game, those folks weren't in front of each other.

So in some instances, they may have been, if they went to computer labs and there were others, but they weren't necessarily in the same game as that person. And so they could be at their home or there wasn't the pressure that you might expect there to be in a different kind of social setting.

And so even there, we still didn't observe these differences in, in how men and women played, except in so much as that women were more likely to use these low yield variants. But I will say that's only one game. And that data is at odds with some work that was done here in a survey experiment by Scott Sagan and a colleague, Valentino, where they found that women were as hawkish, or in some cases even more hawkish than men in their approach to using nuclear weapons.

>> Isabel: Thank you, I'm Isabel. I'm one of the CSAC honor students with Emma, and I'm really curious about the role of emerging technologies in warfare. And I think we're seeing war and tactics move into other domains, space and cyber being two of the ones that I think about a lot.

I'm curious what developments you're seeing in war games, particularly on which emerging technologies are the most interesting or constantly sequential in war gaming decisions that are happening in kind of modern age war games.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: Maybe we do Stacey and then Bethany, if you can talk about kind of what's happening in the big strategy, nuclear side.

>> Stacy Pettyjohn: I feel like you should answer this, Jackie, with your book. But like, so, you know, gaming, emerging tech is one thing you might want to do to understand how valuable it'll be, what the changes are, what changes it might have on things like crisis stability, strategic stability, all of these different.

There aren't, you know, it's difficult to represent, especially at unclassified levels, different domains. And I think this is one of the challenges is that oftentimes like Shriver runs this great space war game and it's super classified, but it's focused on space. And you really, the way that modern operations, military operations are evolving is that they're trying to break down these barriers between the domains and it's all about the connections between them that matter.

And a lot of it is stuff that is invisible. So it's the network, it's cyber attacks, it's jamming of satellites that prevent your GPS from working, or other things. And that is a hard thing to game because it is not physical. And I think it is an area where actually more needs to be done.

And I'm hoping to be running some unclassified games that are focused on thinking about how a war that becomes active in space could affect a broader fight. And it's like doing so in a way where people can understand it because right now there are folks that understand it, but they're all in windowless rooms and it's relatively few.

And I think that stifles the debates and the understanding and the ability to make the broad strategic choices because attacks in space, if you go offensive early, have implications for nuclear command and control, early warning, and could cascade into escalation inadvertently. So it's a hard thing to do.

I have to say that, because with games you're not actually predicting what's going to happen. Some of my former colleagues at RAN came up with like one of the smartest ways to model cyber attacks in games because people would just be like, I'm going to cyber, that I'm going to take out your air defenses.

The whole thing goes down and I win. And we've seen in the real world, when you look at cyber attacks, that their effects are normally pretty ephemeral, you know, hours, maybe days, they're normally geographically limited. And they came up with a very simple stochastic model that differed that based on basically whether the type of target was military, so it was harder to attack versus civilian or dual use, and then the number of defenses, and just found a systematic way to represent it instead of making it some sort of magic button.

>> Bethany Goldblum: So in the context of cyber, we did do a game with Sandia National Laboratories, where we were looking at cyber deterrence and the communication capability trade off there. So the idea that if you need to be able to communicate something about your weapon, your cyber tool, in order to deter the adversary from taking some action, but if you communicate too much, then that or that could leave you open, that reveals your capability, and then it allows your adversary to counter that.

And so those studies are gonna come out. So I can't say about the outcome of that, but it's more from an academic perspective. I know that Jackie's done a lot more work, so I'd really be interested to hear her perspective as well.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: Well, I think so. I used to do classified war gaming at the Naval War College.

And so you think when you're in the classified world that you have more information about these emerging technologies, but you don't necessarily, right? And so you're making decisions within a larger campaign war game about emerging technologies. And you would do it quite often in these really unscientific ways.

So we'd bring in all the best experts, and you'd say, okay, go adjudicate. Adjudicates our fancy war gaming word of saying, what happens next? Okay, adjudicate what happens when the cyber thing happens. And you'd get six people around the table, around the room, and they'd be like, I think it does this and I think it does that.

And it was interesting because I actually went back and looked at all of our experts that had come in and realized, my God, They'd all biased in one direction, but nobody actually knew. Like I was walking the kind of classified halls of, you know, nsa and they didn't know, right?

That's actually a fundamental characteristic of cyber is how uncertain effects are. And so we were in, we were inserting into War games this false certainty about this emerging technology, which was significantly biasing the outcomes of the games in one particular direction. So now when I run unclassified games, I definitely don't have the good information about how all the technologies are going to work on the battlefield.

So instead of saying, well, I'm going to make a best guess, I say, well, what if I create like three different worlds? What if, you know, if I'm looking at how cyber might affect nuclear dynamics, what if I create one world in which cyber is the best it could possibly be?

And what if I create another world in which cyber doesn't work at all and another one where it's in the middle? So I'm making assumptions, but in a very controlled way. And then I can run the game and say, okay, based on these differences that are in the hypothetical world about this technology, if cyber does this, this is how it affects the outcome.

But if cyber is actually not that effective, this is how it affects the outcome. And so I'm not making any sort of kind of probabilistic assessment about how that emerging technology affects the world, cuz I don't know. But I'm saying if it does this, then this is how it affects the world.

And so that's how I often approach emerging technologies, is coming at it with kind of hypotheses about these variances in how emerging technologies might work.

>> Stacy Pettyjohn: That's very scientific. It's almost like you're not a pseudo scientist, Jackie, one of the other things that I do with emerging tech, when we're really trying to understand how it could be used if it were to work and what the pros and cons of it are, is some sort of like matrix, like adjudication.

I don't like. These are games that you determine what happens by arguing. And you really, really need expert players then, and creative ones and then expert adjudicators. And you basically talk it out and you argue and you eventually make a decision, knowing that it may be right or wrong, but you help to illuminate the trade off so you can think those through and capture that, and that's the real value of the game.

>> Bethany Goldblum: Just one more thing to add on that. So in an experimental environment, you wanna avoid having externalities influence the game. And so you don't then have these other folks coming in to adjudicate how things work. And so I think that, that, yeah, as Jackie was saying, it puts a limit on what you can do.

You have to make assumptions about then how the technology works. And so in addition to having different conditions that you could test, you can also put randomization into the behavior of the technologies. But then that also forces an assumption about what you think in terms of how the effects would be manifest.

And so you have to think about how your prior on those effects is influencing the outcome and the decision making.

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: The bottom line is games cannot show you how an emerging technology is going to work. That's actually what modeling and simulation hopefully gets us closer to. But even then, even models and simulations don't take into account training or readiness or in individual or political will, right?

So if anybody ever comes to you and says, I did a game, this is what the technology does, I would discount them, right? But what games can do is they can say, okay, in this world of possibilities, here's the way in which if the technology works, like the models, how we think it might affect those outcomes.

And the bottom line is no one game can tell you that. So you have to look at games iteratively. So if you want to understand the impact of space, you can't look at one game. You have to look over and over and over again and be able to understand how different changes in the way people played the game.

Who played the game, what technologies they used, the assumptions they made about how those technologies are going to work, how those changes in the game end up affecting the outcomes. If one outcome occurs, no matter all the changes, which that never happens. That's crazy. That is a really good sign that that outcome is that it is a high probability outco, right?

But you have to look across a lot of different games.

>> Audience member 1: Thank you. Really fascinating talk and I'm really glad to see that we have women leading war gaming. I mean, when I first came across this topic, I'm like, women in war gaming, really fascinating. So I'm really encouraged and I would be very interested in understanding how you came about in getting into this career and how would you encourage other women to get into this career?

And the second question I would have is, is there a global ecosystem of war gamers and how you exchange notes among allies and even with adversaries?

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: Well, Bethany, why don't you start maybe take the first question and then we can come back and hit the second question about the communities within wargaming.

>> Bethany Goldblum: Okay, so I'm, my day job is as a nuclear scientist. So most of what I do is develop neutron detection systems or methods to ensure that nuclear material is being used for peaceful purposes or that nuclear material is where it's supposed to be. I also do nuclear physics, so I measure nuclear reaction probabilities which are used in modeling for design of different nuclear systems.

So I kind of just stumbled into this. I was actually at the airport and someone called and I, I as about to get on a flight and they were like, hey, somebody have a doc?

>> Jacquelyn Schneider: Is there a doctor around? Can they do a war game?

>> Bethany Goldblum: Pretty much.

And then it was like, okay, well they're boarding now and do you want to participate? And I was like, sure, sure. Because, you know, it was perspective at the time. And I thought, well, there's no way that all of the. There were many projects that part of this Carnegie Corporation of New York funding opportunity that established the project on nuclear gaming in which SIGNAL was born.

And so I just said, yeah, that'd be great. Well, turns out then it did become a real thing and then I was the project director, so I learned on the fly. But I'm glad I did because I feel like that there's a lot of interesting questions we can ask using this platform.

>> Stacy Pettyjohn: Yeah, my path was by happenstance too. I wrote my dissertation on the Israeli Palestinian conflict and then decided I never wanted to study that again. So I got a job at RAND and I went into defense policy. I went from foreign affairs really to defense policy and learned that.

And one day someone came and said, we're going to establish a center for gaming. Do you want to lead it? And I was like, yeah, I've taken some notes, I've played in a few games, I don't know if I'm qualified. And they said, here's your senior mentor who has three decades of experience that you can learn from.