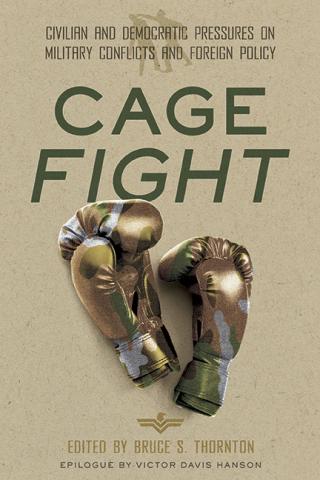

In this Q&A, research fellow Bruce S. Thornton describes Cage Fight, a new book he edited from the Hoover Institution Press, which features contributions from military historians who provide case studies on how the demands of democracy come into conflict with military execution.

Throughout the interview, Thornton cites various historical examples of such conflict that the book’s contributors cite, from ancient Athens, the Civil War, the Cold War, and American interventions in Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq.

Thornton underscores that there is an inherent paradox in democracy: when people are allowed to be free, it opens the possibility of popular dissent and the ability for people to protest the governing institutions that were originally intended to protect that freedom.

Will you talk about the origins of this book?

Bruce Thornton: Cage Fight is the product of Hoover’s Military History in Contemporary Conflict Working Group, chaired by Senior Fellow Victor Davis Hanson. It is the second volume (the first was Disruptive Strategies, edited by Research Fellow David Berkey) that has arisen from the conversations we have in our annual workshop and from the essays of our bimonthly publication, Strategika.

We chose to focus on the topic of civilian-military relations because of the events that took place after the 2020 election. Specifically, we consider the duties of our senior officer corps. These generals and admirals all have obligations to the president under whom they serve. But these officials are also American citizens who have declared an oath to uphold the US Constitution and defend the country from its enemies.

Here is where the dilemma arises. A civilian government enables citizens to participate in political deliberation and, in the voting process, to hold our leaders accountable. The military is based on a hierarchical model. American democracy hasn’t done so well with hierarchies. If you study the history of the United States, there have been flashpoints in which tensions between these two institutions have been on full display. I wanted to explore this aspect of American democracy in my introduction.

The affairs of the military often require secrecy and dispatch. A modern military can't go on, as the ancient Athenians did, debating over issues in the middle of a war and taking votes. But an important part of our political order is indeed the right to free speech and to voice our opinions. Our nation experienced vigorous dissent against the wars in Vietnam and the second Gulf War. Even today, there is tense debate between people who view American aid to Ukraine as a waste of national resources and others who believe Ukraine is a critical line of defense against Russian president Vladimir Putin’s assault on the freedoms of the West and the rules-based international order.

Can this right to hold leaders accountable go too far?

Bruce Thornton: In the first essay, Paul Rahe explains how the people of ancient Athens had taken the principle of accountability, in many senses, to a toxic level, because any citizen could accuse any government official of malfeasance or another crime and there would be a trial. This trial would be heard by several hundred Athenian citizens picked by a lottery. The penalties of a conviction could be exile, a fine, or even death. The great fourth-century orator Demosthenes alerted the Athenians to the dangers of their justice system, in the face of aggression posed by Phillip II of the northern Greek kingdom of Macedon.

Demosthenes said sardonically of Athenian commanders, known as strategoi, They have a greater chance of being executed because of a trial here in Athens rather than dying in battle against the enemy.

Eight Athenian admirals suffered such a fate after the Battle of Arginusae during the Peloponnesian War. Even though they were victorious against the Spartans, six of the strategoi were indicted on a capital crime and executed because a storm prevented them from retrieving the bodies of their dead sailors.

If you know your Greek literature, in Sophocles’ Antigone, you will remember the quarrel between Antigone and the tyrant Creon. Antigone’s brothers Polyneices and Eotocles killed each other while fighting in war. Consequently, the angry tyrant refused to allow Polyneices to be buried with honors. The biggest obligation families had in Greek society was to bury their dead.

So, this whole business of retrieving the bodies was very important, particularly in a naval engagement. If the drowned men are never recovered, that means they can’t reach the underworld and are thus condemned to a “zombie” state for all eternity. This wasn’t a trivial political issue, although politics may have played a part. Nevertheless, that level of accountability is very destructive politically for the city-state. The founders of the United States were very familiar with this story and its lesson of excess accountability in public life.

We want accountability. But if accountability becomes excessive, it can constrain our military leaders’ ability to achieve mission success. In Vietnam, for example, the United States was forced to withdraw troops and end material support for the government of South Vietnam, largely because of the mass protests that took place on US soil. So, this isn’t just an ancient issue, it’s a modern one too.

In the second essay of the book, Ralph Peters explores dissent in the efforts of both sides of the American Civil War. How was that dissent expressed?

Bruce Thornton: The Civil War was a conflict over our future national identity. Some will say it was just a disagreement over tariffs between North and South. That was part of the problem, but the reason for the war was fundamentally about slavery and the nature of American society, in its economic, social, and political dimensions. That is why the debates of that era were so passionate.

That passion manifested itself in various forms of dissent. For example, conscription of newly arrived Irish immigrants sparked riots in New York during the Civil War. Many of these immigrants were incensed that they were liable for service while slaveowners were spared the potential loss of labor from sending their subjects into harm’s way.

Both the North and the South also had the challenge of citizens among their populations who sympathized with their military adversary.

In chapter three, Peter Mansoor’s essay talks about the history of military dissent against elected powers. What did the founders believe was the appropriate relationship between politicians and high military brass, especially in times of conflict?

Bruce Thornton: As the old saying goes, politics ends at the water’s edge. In other words, our quarrels shouldn’t be seen by anyone outside the family. We don’t want our divisions to be exploited by our enemies, especially during war. But then again, do members of the military not have First Amendment rights? Under the uniformed code of military conduct, military officers aren’t permitted to freely criticize or undermine their commanders, including the president of the United States, who is the commander in chief of the US armed forces.

The role of the president’s military advisors, especially the Joint Chiefs of Staff, are to provide him with counsel on matters of defense, but their duties should be clearly defined.

Let’s look at this issue from a historical perspective. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, European aristocracies were mired in dynastic conflicts. One of those conflicts was the Seven Years’ War, in which the British and French fought each other not only in Europe but in North America, where both powerful nations had colonial interests.

For colonists like George Washington, who fought as a militia officer on the side of the British, their experience of fighting was not in the mass conscripted armies of Europe, because the colonies were granted a great deal of self-governance. By their own consent, they participated in the larger army (what was called the Patriot Army) during that conflict. This quasi-sovereignty that the colonists enjoyed became the basis for later struggles with the British.

In addition, these European dynastic struggles created a huge distrust among the colonists about standing armies. The prevailing opinion among the colonists was that militias were called up and then disbanded when the conflict was over. Militias voted in their own officers. By contrast, professional armies had a process for selecting and appointing officers from the top down.

The distrust of the standing army runs throughout American history. We have movies like Seven Days in May about an attempted coup by generals against the president of the United States.

The First Amendment’s guarantees of freedom of speech and assembly, which enable citizens to air grievances against the government, just adds another layer of complexity to this challenge. I’m not sure it is a challenge that can be solved without a dangerous diminution of freedom. President Abraham Lincoln restricted speech and press freedoms during the Civil War. Shortly after America’s entry into World War I, President Woodrow Wilson signed the Sedition Act of 1918, which criminalized certain types of speech, expression, and demonstrations. Some people argue that the Patriot Act, which expanded state surveillance to combat terrorism, was an unconstitutional breach of citizens’ rights to due process.

At this point, how do you reform the national security state when threats are so persistent?

Bruce Thornton: This type of paradox was noticed by Winston Churchill when he was writing The Gathering Storm, the first volume of his history of the Second World War. To paraphrase Churchill, there are structures of democracy that are inherently paradoxical, and they’re just part of the price that we pay to be free. When you make people free, you open the possibility of people undermining governing institutions.

This is a balancing act that we have over the years tried to maintain. I believe that in the post–World War II era, we have been moving too far in the direction of curtailing freedom.

The founders created a mechanism of checks and balances to prevent abuse of power by any one of the three branches of government. But that mechanism has come under revision over the past one hundred years. There has been a weakening of those safeguards and a tendency toward transferring power to a technocracy of specialists who govern within the federal bureaucracy.

In recent times, we have seen social media giants working with the FBI to remove content from their platforms that they deem dangerous to our national security. I don’t think this is a road we want to continue to go down.

In Federalist 10, James Madison wrote that factionalism “is sown in the nature of man.” These are wise words. By their fallen nature, men will try to aggrandize as much power as possible to serve their interests and thus will inevitably struggle with one another over property or other earthly goods. It would be nice if people thought about the greater good. Some people do, but it usually doesn’t work that way. That is why we need to preserve our constitutional order, in which government is obliged to guarantee individual freedom while also respecting a system of checks and balances that doesn’t allow any single individual or faction from becoming too powerful.

Williamson Murray’s essay addresses how George Kennan’s policy of containment of Soviet influence and power prevailed in public debates over isolationist sentiments in America during the early Cold War period. Today, both major political parties have their hawkish and dovish factions when it comes to the projection of American power in foreign affairs issues. What can we learn from the Cold War era about the merits and flaws of these diverging perspectives?

Bruce Thornton: One fact that we must remember about the Cold War is that there was a balance of terror called “mutually assured destruction,” or MAD. If you grew up when I did, you would remember that in October 1962, during the Cuban Missile Crisis, we probably came closest to nuclear Armageddon as ever before or since.

In addition to this standoff, the US and Soviet Union contested each other’s power and influence through proxy wars, espionage, and military competition throughout the world. Our victory in the Cold War was achieved largely because the Soviet economy could not keep up with that of the United States in producing sophisticated weaponry.

The Cold War has unique characteristics that make it difficult to apply to other circumstances, but there are some points of recognition. There are people who study the Peloponnesian War and compare it to the Cold War. Athens was powerful on the seas and Sparta was powerful on the land. Athens and Sparta, respectively, wanted to fight that war on their own terms. The two sides engaged in a tournament of proxy wars and attempted to peel back allies.

During the Cold War, containment worked in the end. But ask yourself: Does a leader like Ronald Reagan always come along when you need him? We don’t like to think this way, but in many cases fate plays a role in historical outcomes.

If you think about Nazi Germany in May 1941, it had achieved control over most of Europe. It enlisted some countries as allies, coerced others to cooperate, and occupied those who resisted.

What if Hitler didn’t invade the Soviet Union? How would that whole postwar world have looked? Adolf Hitler may have been able to preserve his reign over Germany.

Also imagine that there was no atomic bomb and the US hadn’t used it to end the war with Japan. Russia had hundreds of thousands of troops in Eastern Europe. If we redeployed all our troops from Europe to Japan, the whole continent would have been left exposed to Soviet aggression. All the great European powers—Great Britain, France, and Germany—were exhausted by the war. Thus, without US support, the Soviet Union would have been able to take over Europe uncontested.

But American involvement in World War II was brought about by a unique set of circumstances. Prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, it would have been inconceivable for most American citizens to support US troop presence in both the European and Pacific Theaters. In sum, I think it is very difficult to find historical lessons that could be useful today because many large conflicts are driven by wildcard factors that are almost impossible to identify. But this makes it all the more important that we study the past diligently and carefully so that it speak to us.

The last essay, by Bing West, discusses dissent among the military, civilian government, and citizens during the wars of Korea, Vietnam, and Afghanistan. How does such dissent during wars impact our defense policy making?

Bruce Thornton: It is kind of a gloomy assessment, but really, it’s an age-old lesson that you must respond to aggression before it reaches a certain point. The Europeans didn’t do that in the 1930s. They didn't take on Hitler.

I think even in September 1938, during Hitler’s meeting with British prime minister Neville Chamberlain in Munich, the German army general staff didn’t believe there was any way they could take Czechoslovakia, which was allied with France. Czechoslovakia was not a tiny little helpless country at the time. But Hitler decided to roll the dice earlier when he remilitarized the Rhineland and launched the Anschluss in Austria. Hitler was a better psychologist than his generals were. He understood the failure of nerve that had been afflicted on Great Britain and France after World War I.

We should have learned that lesson. At the first signs of aggression, we need to hit the enemy hard. Today, there are continual calls to ramp up support for the Ukrainians against Russian aggression. But why did we let ourselves get to this point, where we have two choices, both of which are kind of bad. And it is not like we didn’t know what Vladimir Putin was capable of. We knew just how brutal he could be when in the 1999 Chechen War, he made Grozny look like Thebes, utterly destroyed after Alexander the Great’s campaign in the fourth century BC.

We all knew about Putin’s vision to restore an ethno-Russian empire.

In 2008, Putin tore off parts of Georgia and basically got away with it. He also got away with the annexation of Crimea in 2014. Yes, there were now sanctions in place against Russia and a lot of tough rhetoric from American and European leaders.

But again, this falls into another paradox of democracy, which Alexis de Tocqueville talks about in Democracy in America, and that is, governments of sovereign citizens with regularly scheduled elections tend to kick the can down the road.

We believe that we can use diplomacy to end the war. But Putin took a year to get his invading army to Ukraine, and what were we doing? We were using inflammatory rhetoric and making threats. Then suddenly, he decides to invade, and we’re shocked.

And then, once we start to help push back against Russian aggression in Ukraine, we do so with half-measures. The president of the United States said, “We’re not going to deploy troops to Ukraine.” So, he took a piece off the chess board right from the start.

Despite that pronouncement, it is unlikely we could have deployed troops in support of Ukraine anyway, because it would be too costly politically. Again, we come back to the paradox: the price we must pay for our political freedom.