A top-down model of governance in Russia hinders innovation, prosperity, and freedom in a country already facing brain drain and an aging population, experts said at a recent Hoover event.

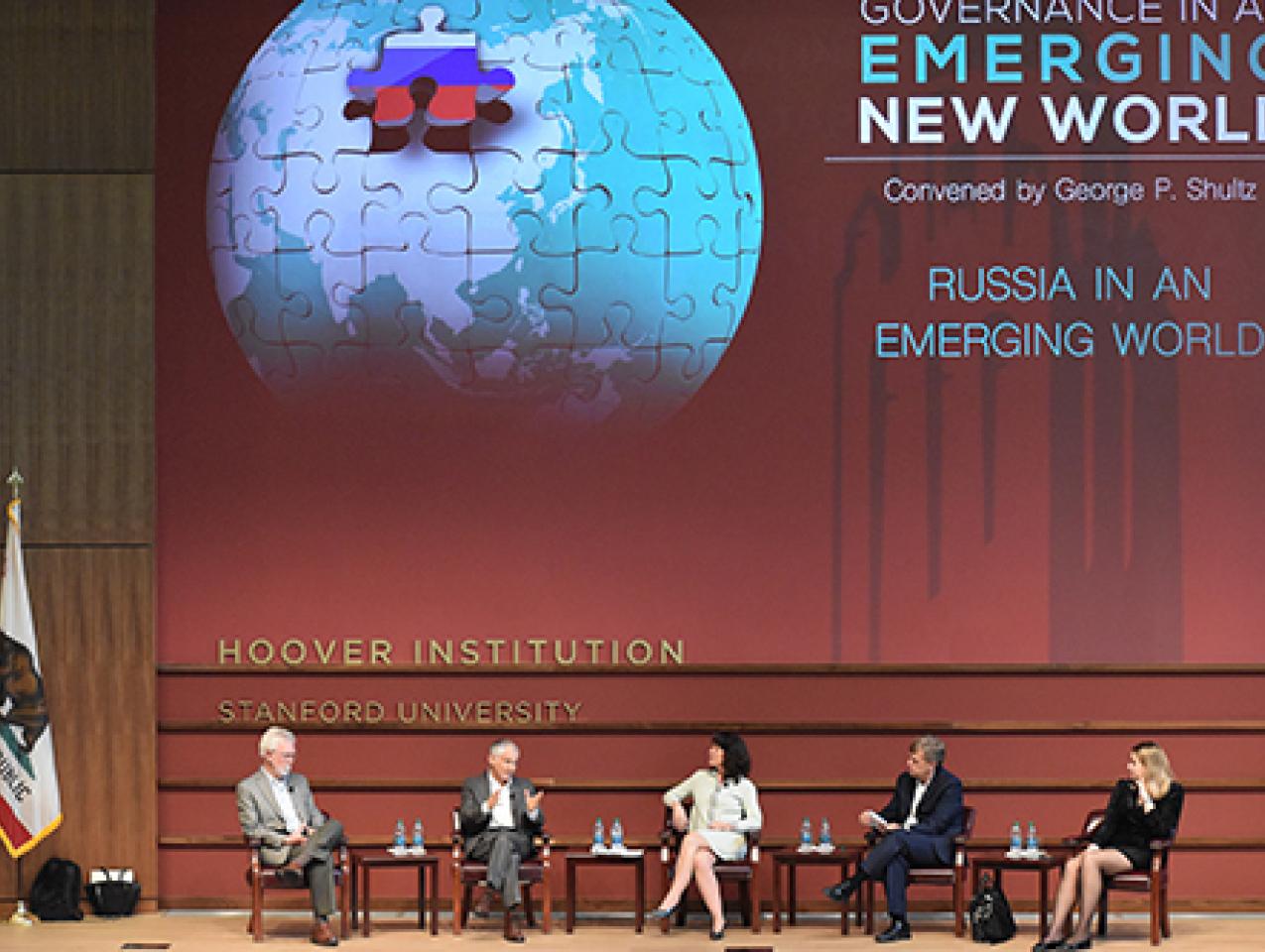

On Wednesday, the Hoover Institution kicked off the Governance in an Emerging New World project led by Senior Fellow George P. Shultz. Through discussions and research papers, the effort will explore some of humanity’s most challenging issues over the course of the 2018–19 academic year.

“The world is changing rapidly,” Shultz said in his introduction. “We’re trying to figure out how to understand it better. Initially, we’re going to say, ‘What’s the impact on Russia?’”

The “Global Governance in an Emerging World: Russia” panel included Michael McFaul, Hoover senior fellow and former US ambassador to Russia; Hoover Senior Fellow Stephen Kotkin; moderator Kori Schake, International Institution for Strategic Studies deputy director-general and former Hoover research fellow; and David Holloway of the Freeman Spogli Institute.

Technology crossroads

McFaul said that while Russia has many problems, the people are richer and have higher standards of living than ever before in Russian history.

“And yet, as I argue in my paper, Russia is still underperforming,” especially in tech sectors, McFaul said. “There is no Silicon Valley in Russia,” while other countries like Israel have cultivated such communities.

McFaul said that autocratic rule in Russia is a hindrance to innovation, though pockets of excellence exist in areas like military industries.

One problem, he said, is that property rights in Russia are not guaranteed by the rule of law in Russia, but by the state. Russia has also become less democratic over the last fifteen years. “Those conditions have chased away capital.”

On top of this, he continued, President Vladimir Putin’s aggressive foreign policy has resulted in international sanctions and investor wariness about Russia as a place to do business, he said.

Under sanctions, Putin seems to want to steer Russia on its own independent course, which McFaul pointed out is likely not a viable strategy.

And while Putin often talks about the importance of sovereignty, the Russian leader should practice what he preaches in the Ukraine and Crimea, McFaul added.

Misplaced ingenuity

Kotkin said the case of Russian cheating and doping in the recent Olympic Games reflects Russian cunning and ingenuity at breaking the rules and covering their tracks. “The Russian story is a difficult one to unwrap.”

He said Russia would be better served if it pursued legitimate activities with that same ingenuity. It’s a lesson to the West that authoritarians in Russia are surprisingly bold in advancing their interests.

Meanwhile, those authoritarian regimes have learned to use technology to surveil and repress their own people, he said. Perhaps counterintuitively, democratic governance has been severely disrupted by authoritarians in Russia and elsewhere by technological manipulation.

Kotkin said there is some hope. “The weakness of poor demography could actually be a strength if robotics” became widely spread in Russia.

Hydrocarbon revenues are the linchpin of the Russian economy right now, but that could change is renewable energy became more available worldwide, according to Kotkin. “I wouldn’t necessarily predict a fundamental collapse” of Russia, he said.

While the top-down model of governance in China has produced huge growth, it is not working in Russia, Kotkin said. The difference is that China has created market opportunities within its framework and adapted technology and trade secrets from other countries.

He applauded President Trump’s instincts to cultivate a better relationship with Russia.

Legitimacy in Russia

Holloway explained that Russia has experienced enormous change in its governance in the last thirty years since the fall of the Soviet Union. “This was a social trauma that was registered in the population in the rapid decline of life expectancy of Russian men” to fifty-seven years of age at one point.

As a result, the choice facing Russians would seem to be whether to continue following the recovery they have known under Putin or return to a more chaotic period like in the 1990s. This makes change more difficult, Holloway said.

In the mind of the average Russian, Holloway said, “stabilization is important,” they still remember the skyrocketing inflation and difficulty of getting food in the 1990s.

Yet Holloway reminded the audience that Putin is well aware of his country’s technology lag, with the leader calling for his country to ride the “technological wave.”

Other aspects of Russian legitimacy—such as cultural values, the Russian church, and successful foreign policy measures—are important to both leadership and the people, Holloway said.

Maria Smekalova of the Russian International Affairs Council presented a paper by Igor Ivanov, the former foreign minister of Russia. Six papers in total were written by the participants for this event.

Smekalova said Russia’s “brain drain” due to educated people leaving the country and a rapidly aging population are its two key challenges. “That would be the biggest problem facing the country today,” she said.

In his paper, Ivanov wrote that after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the United States and its allies attempted to establish an international system based on the principles of a “unipolar world.”

Ivanov calls for a more stable and reliable “multipolar world. . . . We have been talking multipolarity for two decades now, but still cannot implement the concept,” he said.

Click here to read the papers of Michael McFaul, Stephen Kotkin, David Holloway, Anatoly Vishnevsky, and Ivan V. Danilin.

Future events

The project aims to assess long-term and fundamental demographic shifts, the information and communications revolution, advancing technology—such as artificial intelligence and 3-D printing—and how these changes affect domestic and international policy strategies.

Events will continue roughly every three weeks throughout the 2018–19 academic year. Discussions have already been planned for October 29 (China); November 13 (communications and technology); and December 3 (Latin America).

In a letter announcing the project, Shultz cowrote, “We will explore the implications for our democracy, our economy, and our national security, and for other countries.”

MEDIA CONTACTS

Clifton B. Parker, Hoover Institution: 650-498-5204, cbparker@stanford.edu