- Campaigns & Elections

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- State & Local

- The Presidency

- Congress

After the 2004 presidential election, Republicans appeared to be in good shape. They had won the presidency, had a 30-seat margin in the House of Representatives and 55< U.S. Senators. Four years later, the situation is very different. Republicans lost 31 House seats, six Senate seats, and control of both chambers of Congress in the 2006 midterms. In addition to losing the presidency, Republicans lost approximately 20 more House seats and at least six more Senate seats in the 2008 elections. Not since the Hoover administration have Republican fortunes been reversed so clearly and precipitously.

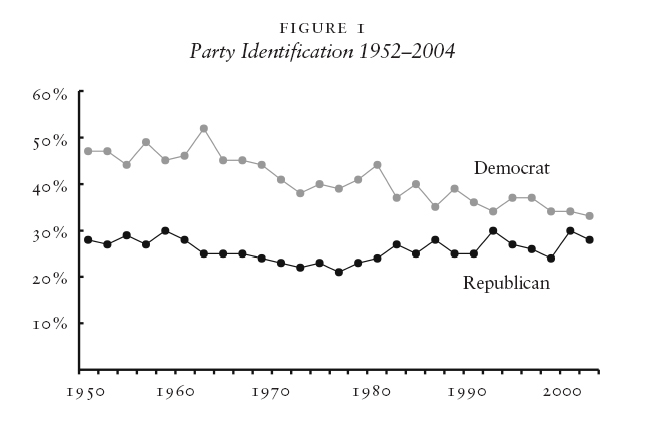

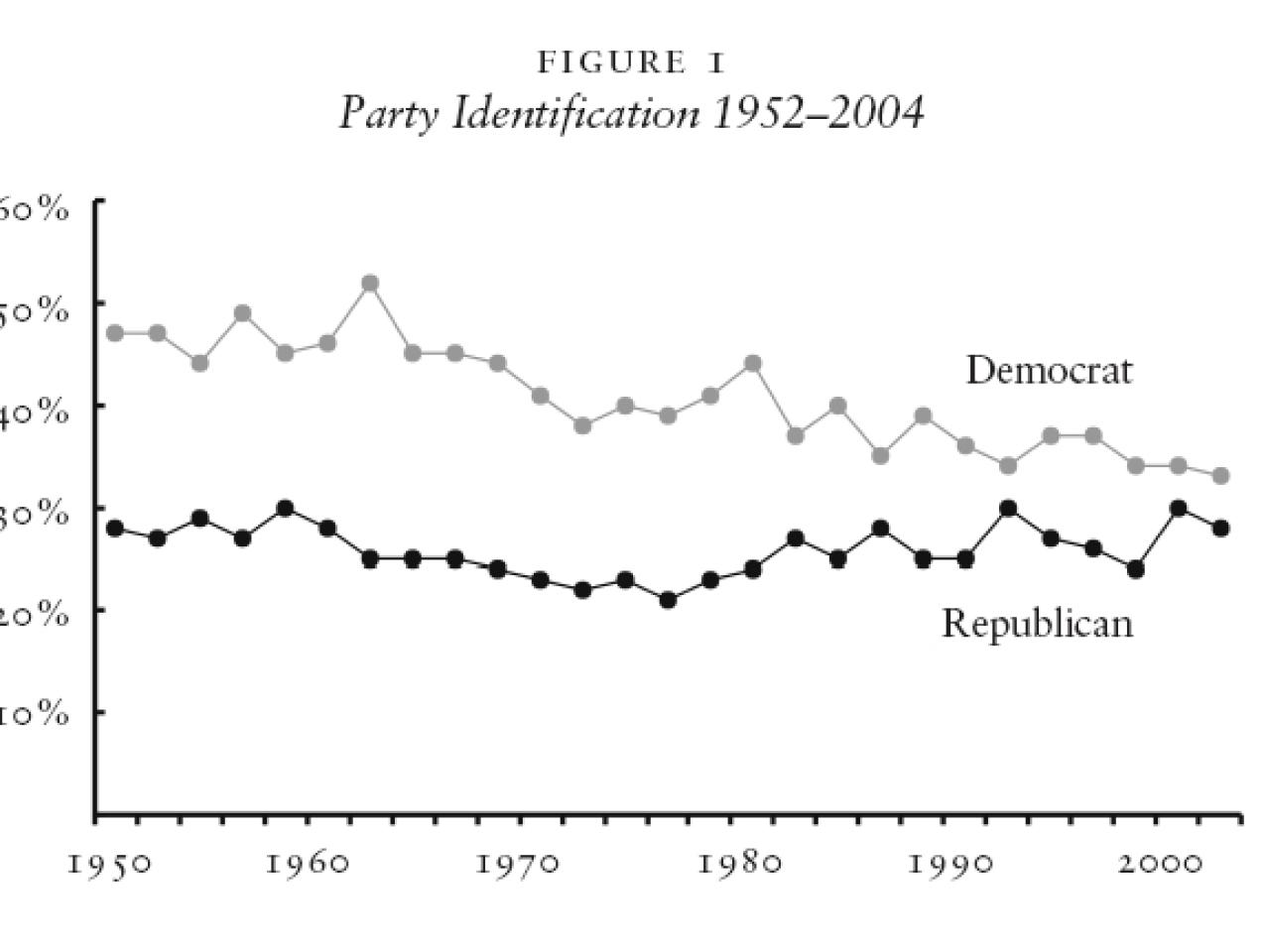

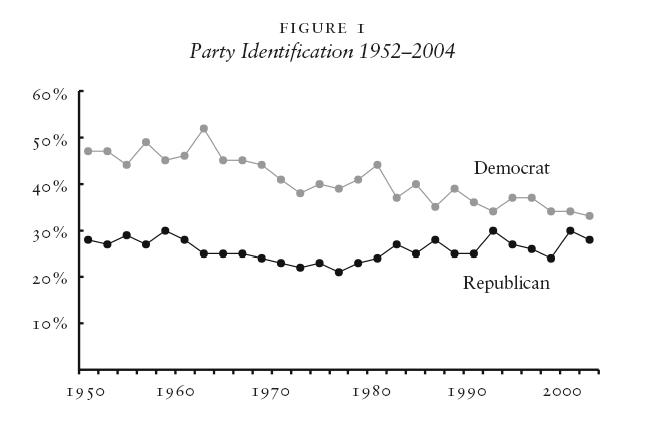

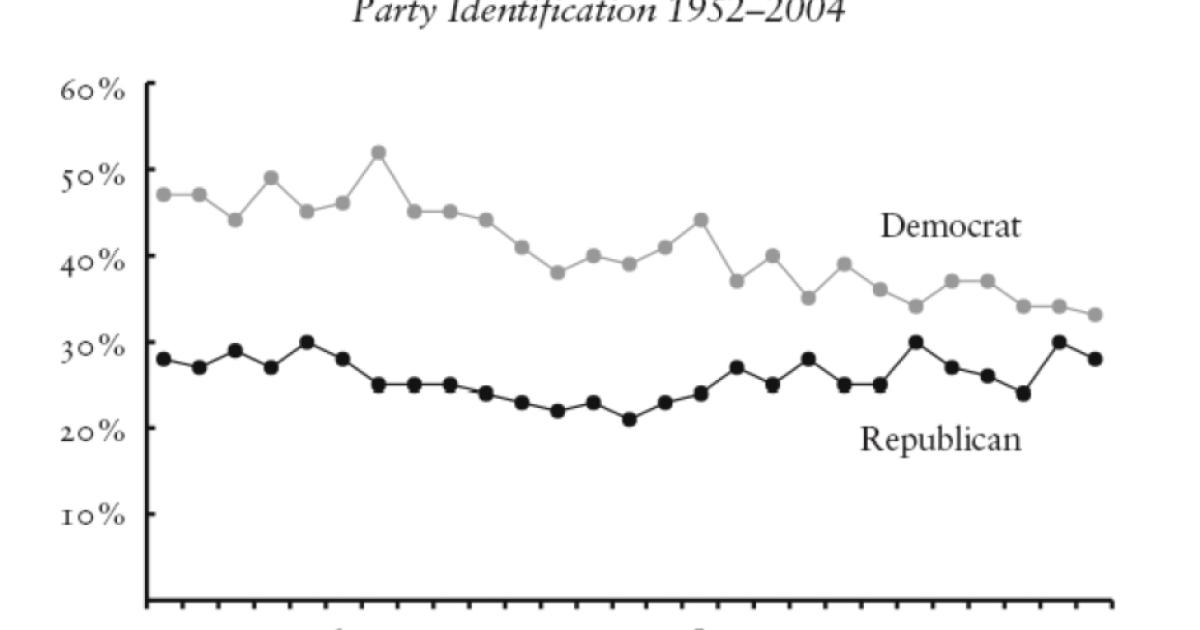

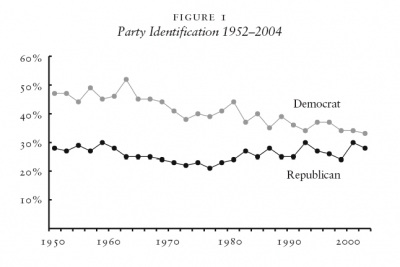

These shifts are, we think, indicative of a more fundamental change in partisan loyalties that could reshape American politics for a generation. Starting in the late 1960s and continuing through 2004, Republicans posted consistent, steady gains in standard measures of partisan support, as shown in Figure 1. Democrats held almost a 20-point advantage over Republicans in the period from 1952, when the American National Election Studies (anes) started measuring party identification, through the mid-1960s. Starting in the 1970s and accelerating during the Reagan years, Republicans narrowed this gap to less than five percent, with near partisan parity in the 2000 and 2004 presidential elections. At the same time, the geographic bases of the parties shifted, with Democrats winning the Northeast and West Coast and Republicans holding almost everything in between.

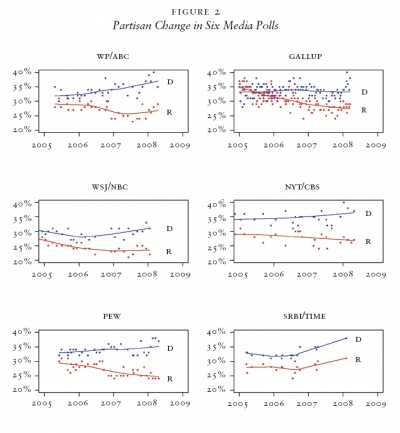

In four short years, Democrats have reclaimed most of the ground they lost during the Reagan era. Figure 2 shows the percentage of Democrats and Republicans in six different media polls between 2005 and 2008. For each polling organization, the lines show the trend in Democratic self-identification and the trend in Republican self-identification, with Democrats now having an advantage between 5 and 10 percent. The question wording and procedures used by the different polls vary, but the pattern is unmistakable. Pew, Gallup, New York Times/cbs, Washington Post/abc, and Wall Street Journal/nbc all show party identification moving away from the Republicans. Only the Time polls show gains for Republicans and even here the net shift is toward the Democrats.

In this article, we investigate why voters shifted toward the Democrats following the 2004 election and its short- and long-term implications for party competition. Part of Republicans’ difficulties comes from widespread dissatisfaction with the Bush administration and its handling of the economy and the war in Iraq. These are retrospective evaluations whose effects will tend to diminish over time. But another cause of Republican troubles appears to be the ideological positioning of the Republican Party, particularly on social issues. The positions that appeal to the Republican base are repelling moderates the party needs to maintain its long-term competitiveness. These voters are not lost to Republicans — yet. Most consider themselves independents or leaning or weak Republicans, not Democrats. They are not liberals and remain closer, on average, to Republican positions than those espoused by the Democrats. But they are up for grabs.

The nature of partisan change

While the polls generally agree about the magnitude of the Democratic shift, these surveys do not tell us why such a shift has occurred. To understand why Republican support has fallen off so dramatically, we utilize a unique data source. Starting in 2004, YouGov/Polimetrix has interviewed samples of American voters using Web surveys.

The sample used here consists of 12,881 respondents who participated in at least one interview during the 2004 election campaign and were re-interviewed in 2008 as part of a series of surveys for the Economist. This allows us to trace individual voters over this time-span. We can identify actual voters who said they were Republicans in 2004, but who had become independents or even Democrats by 2008.

In both 2004 and 2008, our respondents were asked to place themselves on the traditional seven-point party-identification scale. This is a two-part question that first asks:

Generally speaking, do you think of yourself as a Republican, a Democrat, an independent, or what?

Democrats and Republicans were then asked whether they are a “strong” or “not-so-strong” Democrat or Republican, while independents and others were asked if they “lean toward” one party or the other. This yields a seven category scale: strong Democrat, weak Democrat, leaning Democrat, independent, leaning Republican, weak Republican, and strong Republican.

Very few Republicans actually become Democrats. Only 1.2 percent of the strong Republicans and 8.0 percent of the weak Republicans from 2004 say they are Democrats or lean Democratic in 2008. Instead, the decline of Republican strength occurs when strong Republicans become weak Republicans, weak Republicans become independents, and independents lean more Democratic or even becoming Democrats. These voters are not necessarily permanently lost to the Republican Party, but this has the look of an emerging party-realignment, with the Republican base shrunken substantially.

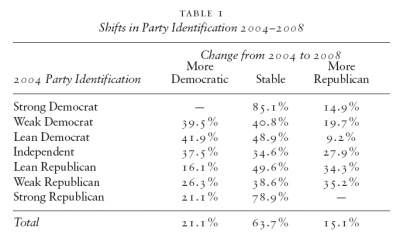

Some more detail on the nature and size of the Democratic shift is shown in Table 1, which shows how respondents in each of the seven party-identification categories moved between 2004 and 2008. For example, among pure independents (i.e., independents who did not lean toward either party), 34.6 percent were stable and gave the same answer in 2008 as 2004. Of the remainder, 37.5 percent moved in the Democratic direction (either identifying as weak or strong Democrats or as leaning toward the Democrats) while 27.9 percent moved in the Republican direction, for a net gain of 9.6 percent for the Democrats. Overall, we see a shift of 6.0 percent toward the Democrats, consistent with the shifts seen in media polling.

Respondents in the two extreme categories — strong Democrats and strong Republicans — can move only in one direction. Because there are only seven categories, strong Democrats cannot become “stronger” on this scale. Similarly, strong Republicans can only become more Democratic. However, if we compare strong Democrats with strong Republicans, we see that the Democratic losses among strong identifiers are smaller than the corresponding Republican losses among their strong identifiers. The same pattern holds for weak identifiers and leaners. Weak Republicans actually became more Republican by a 35.2 percent to 26.3 percent margin, but weak Democrats became more Democratic by an even larger 39.5 percent to 19.7 percent margin. Across the board, Democrats do better with their identifiers than Republicans do with theirs. The Republican net-losses are smallest among their base of strong identifiers and somewhat larger among weak Republicans and largest among independents leaning Republican.

What caused the Democratic shift?

What caused these voters to switch their party identification between 2004 and 2008? The increase in Democratic support was not limited to independents, who typically exhibit more volatility in their partisan loyalties than voters in each party’s base. These are, for the most part, voters who supported George Bush’s reelection in 2004 and voted for Republican congressional candidates, but who have subsequently become more Democratic (or, perhaps more accurately, less Republican). One can think of any number of reasons for them to have moved in this direction, but most explanations fall into two broad categories: dissatisfaction with the performance of the Bush administration or estrangement from the Republican Party on ideological grounds. An obvious answer would appear to be President Bush’s unpopularity.

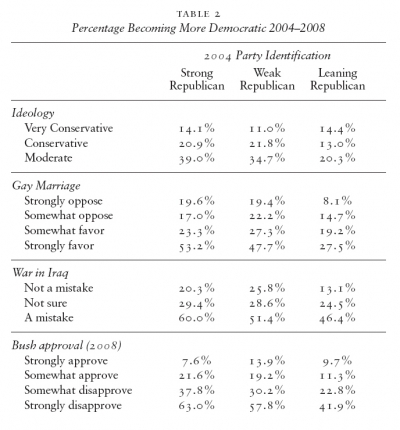

Presidents and their parties are usually blamed for bad economic news (and sometimes credited for positive news) that occurs on their watch. The second Bush administration has had a large share of bad economic news with little positive to report. Rapid increases in oil prices and the most severe financial crisis since the onset of the Great Depression alone would be enough to make a president and his party unpopular. In fact, much of the decline in Republican support is associated with negative assessments of President Bush. Table 2 shows the percentage of Republicans who shifted toward the Democrats between 2004 and 2008 among different groups of voters. For instance, 63.0 percent of persons who were strong Republicans in 2004 and strongly disapproved of President Bush’s job performance became more Democratic. There are, of course, not many Republicans (much less strong Republicans) who came to hold such a negative assessment of Bush, but those who did are now much weaker Republicans than they were previously.

However, Bush’s steep decline in popularity, as well as Republicans’ loss of control of Congress, preceded the economic events of 2007–08. An obvious alternative explanation is the war in Iraq, which 54 percent of the public now thinks was a mistake. Opposition to the war is much stronger among Democrats than Republicans, but even among Republicans enthusiasm for the war has waned considerably over the past five years. A majority of strong and weak Republicans who turned against the war by 2008 moved in the Democratic direction. This is a fairly sizable group (21 percent of Republicans now consider the war to be a mistake or aren’t sure), and the proportions becoming more Democratic are large. The public has tired of the war in Iraq and one casualty may be the Republican Party.

Dissatisfaction with the performance of President Bush and the U.S. intervention in Iraq are matters of retrospective evaluation, not fundamental ideology. We also have examined the relationship between voters’ ideological preferences and their support for the Republican Party. Among “very conservative” Republicans, between 11.0 percent and 14.4 percent became more Democratic between 2004 and 2008 — a fairly modest number, offset (except among strong Republicans) by larger numbers of voters who became more Republican. This is the new Republican base: ideologically committed to conservative positions across a wide range of issues, including not only taxes and the size of government, but also abortion, gay rights, immigration, and gun control. Among those who consider themselves just “conservative” (and not “very conservative”) there is more movement in the Democratic direction (between 13.0 percent and 21.8 percent become more Democratic), but the movement is not that big or significant.

In contrast, among self-described “moderates,” there have been large losses, with 39.0 percent of the strong Republican moderates becoming more Democratic. These are (or were) marginal Republicans and the last four years have shrunken their numbers substantially. The larger losses among peripheral Republicans mean that the Republican base is not just smaller, but more conservative than it was before 2004.

Nowhere is this trend more apparent than on the issue of gay marriage. In 2004, all eleven states which had a referendum involving gay marriage on the ballot voted to ban the practice. A majority of voters still oppose gay marriage, as evidenced by the passage of Proposition 8 banning gay marriage in California. The Republican Party is clearly associated with opposition to gay marriage, and most Republican voters also oppose it. However, Republicans who do not share the party’s enthusiasm for attacking gay marriage have weakened their ties to the party. Approximately half of the Republicans strongly in favor of gay marriage became more Democratic between 2004 and 2008.

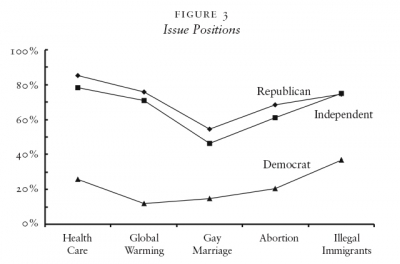

Dislike of President Bush and his policies was one driving force behind movement toward independence and becoming Democratic. It is possible that some Republicans moved Democratic because on issues not specifically related to President Bush, they favored Democratic issue positions. In order to test this hypothesis, we selected a set of issues where party differences are apparent: universal health care, worries over global warming, gay marriage, abortion rights, and illegal immigration. The Republican response was coded as follows: opposed to universal health care, think effects of global warming haven’t started, opposed to any legal recognition of same-sex couples, favor no abortions or abortion only in cases of rape and incest and, finally, favor deportation of illegal immigrants. Figure 3 plots the percent taking the Republican response for each of the three categories of respondents: stable Republicans, Republicans who moved to independent, and Republicans or independents who moved to Democratic. The results consistently show that those who remain Republican are more likely to favor the Republican position on these issues. However, the opinions of Republicans who moved to independent are quite close to the opinions of stable Republicans. Only those respondents who now identify as Democrats are, on average, between 40 and 60 points different from stable Republicans in their positions. Those who left the Republican Party to become independents or Democrats were more likely to favor universal health care, gay marriage, pro-choice abortion rights and believe that global-warming effects were already present. Only on deporting illegal immigrants is the support from stable Republicans and Republicans who moved to independents equivalent. Thus, a combination of disliking President Bush and his policies and beliefs that the government should do more to guarantee health care, combat global warming, ensure rights for same-sex couples, maintain or strengthen pro-choice abortion rights and not deport illegal immigrants moved a significant number of Republicans toward the Democratic Party.

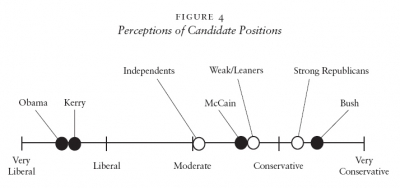

The shape of the new electoral landscape is shown in Figure 4. The empty circles in the diagram show the average position of strong Republicans, weak or leaning Republicans, and independents on a five-point ideology scale (ranging from “very liberal” to “very conservative,” with intermediate positions labeled “liberal,” “moderate,” and “conservative”). The solid circles in the diagram show the positions of the 2004 and 2008 presidential candidates as perceived by these voters. Not surprisingly, strong Republicans are to the right of weak and leaning Republicans, who are to the right of independents. There is no real discrepancy between perceptions of Barack Obama and John Kerry, who are considered by this group to be about halfway between the “liberal” and “very liberal” labels. (Interestingly, Democrats perceive their candidates as being more moderate than Republicans do, but our focus here is on Republican voters.) President Bush is perceived as being almost as far to the right by these voters as Kerry and Obama are to the left. John McCain, on the other hand, is judged to be fairly close to the center, almost on top of the average location of weak and leaning Republicans.1

In electoral competition, the median position will, ceteris paribus, defeat any other position. In 2008, we witnessed the anomaly of a better situated candidate — McCain — doing worse than a more extreme candidate — Bush — did in the preceding election. The problem is that other things are not equal in this case. The combination of a poor economy, an unpopular war, and a party (rather than a candidate) positioned too far to the right is too much for a candidate to overcome. Even quite explicit attempts by McCain to distance himself from the Bush administration did not convince many voters that he represented a real break from Bush.

It is important to note that these voters are still closer to either the Bush or McCain positions in terms of general ideology than they are to either of the Democratic candidates. The Republican Party doesn’t have to move too far to recapture these voters. The dilemma Republicans face, however, is that the Republican base prefers to have candidates close to their own views on social issues, even if this means losing elections.

2008 and beyond

The evidence of a significant erosion in Republican support is consistent, but its meaning is unclear. Dissatisfaction with the state of the economy or the war in Iraq or Bush’s job performance are matters of retrospective evaluation. The public was, at one point, supportive of the war and of Bush. That they turned sour on these does not necessarily have long-term implications for the viability of Republican candidates. In 1964, Lyndon Johnson won an fdr-like victory over the Republican candidate, Barry Goldwater, capturing over 60 percent of the popular vote and 486 Electoral College votes. On the congressional front, Democrats held 68 Senate seats and 290 seats in the House of Representatives. Articles abounded on the dismal future of the Republican Party, yet in 1968, Richard Nixon defeated Hubert Humphrey and Republicans dominated presidential elections for the next 40 years (7 of 10 presidential elections, to be exact). In 1976, however, a poor economy and the residue of Watergate prevented Republican Gerald Ford from being elected (though he came close). Yet the presidency of Jimmy Carter, who beat Ford, was a single term, and Republicans won five of the subsequent seven presidential elections. The Republican comebacks from 1964 and 1976 were largely the result of the failed policies of Johnson and Carter and not of any shifts in permanent party-identification toward the Democrats. Such short-term fluctuations in party identification are the norm, whereas relatively permanent party realignments are often forecast, but rarely realized.

We cannot rule out a similar trajectory today, with the trends that we have identified being transitory rather than permanent. But it is also possible, and in our judgment more likely, that we are witnessing an election similar to 1980, in which the election signified a longer-term trend that lasted nearly a quarter century. Today we have two parties with quite distinct ideological positions and electoral bases. The Democratic base is urban and liberal, while the Republican base is suburban or rural and conservative. The problem for Republicans is that their base is slowly shrinking and they cannot win without the support of moderates.

Bush’s reelection strategy in 2004 depended upon mobilizing the Republican base. This strategy succeeded brilliantly in securing his reelection, but the perils of playing to one’s base are evident in the losses Republicans have incurred among moderates and moderate conservatives. This has been compounded by the unpopularity of the Bush administration and the war in Iraq. The 2004 strategy of mobilizing the Republican base seems, in retrospect, to have been an effective way of winning a battle but losing the war. Despite nominating a candidate in 2008 who is perceived by most Republicans to be less conservative than George W. Bush, moderate Republicans have been fleeing the party in large numbers.

In 2008, the McCain campaign tried to focus on foreign policy and personality, areas in which McCain was perceived to be more experienced and less risky than Obama. McCain called himself a “maverick” and tried to separate himself from President Bush on several issues (such as global warming). But on most issues the actual differences between McCain and Bush were small. On abortion, gay marriage, and universal health care, McCain’s positions appeal more to the base than to the switchers. In the end, none of this positioning could have much impact in the face of a financial crisis, regarding which Republicans, rather than Democrats, seemed like the riskier alternative.

The national exit poll showed that McCain won the votes of 90 percent of self-identified Republicans, while Obama won 89 percent of self-identified Democrats. Unfortunately for McCain and Republicans, only 32 percent of voters now call themselves “Republicans” (compared to 39 percent who say they are Democrats) and Obama won the independent vote by a 52–44 margin. Particularly concerning for Republicans is that 18- to 24-year-olds voted overwhelmingly for Obama (by a 66–32 margin).

The Republican Party left in the Senate and the House is more conservative than in any of the Bush Congresses, as Republican losses were predominantly moderates like Chris Shays of Connecticut. The average Republican in the Senate has shifted rightward and the policies he prefers are distinctly to the right of those preferred by the average voter in the electorate. The voters who left the Republican Party over the last four years are like the independents who make up about a third of the electorate — political moderates — and unless the Republican leadership can figure out how to combine fiscal conservatism with moderate views on social and other issues, the trend away from the Republican Party is likely to continue.

After any electoral defeat, there is always a predictable debate between those who attribute the loss to a compromise of principles versus those who think not enough was compromised. The post-election analysis among Republicans will have to deal with the question of declining membership and what issue-position mix will bring back lost members and appeal to independents. The declining Republican base makes it obvious that purity on social issues is an unpromising strategy for a conservative party that needs to widen its appeal. A political party that starts an electoral cycle with 7 percent fewer party identifiers than its competitor and a base that prefers policies to the right of independents and moderates is set up for a long, dry run similar to that of the post-fdr era Republicans.

1 On most measures, leaning Republicans appear to be slightly more Republican than weak Republican identifiers, but these differences are fairly small. To simplify the presentation, we have grouped weak and leaning Republicans together in this analysis.