- Military

- Campaigns & Elections

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- State & Local

- Law & Policy

- History

After the 2004 presidential election, Republicans appeared to be in good shape. They had won the presidency and had a 30-seat margin in the House of Representatives and 55 members in the Senate. But two years later, Republicans lost 31 of those House seats, along with 6 senators, and fell further in 2008: 7 additional seats lost in the Senate and more than 20 in the House. Numbers alone should have caused Republicans concern, but the alarm runs deeper: for the first time since 1980, the dynamics of party identification have shifted, and Republicans now clearly number fewer than Democrats or independents.

Data collected by the six major polling firms in 2005–8 show an increase in Democratic self-identification at the expense of Republican self-identification. To varying extents, polls by five of the firms—Pew, Gallup, CBS/New York Times, ABC/Washington Post, and NBC/Wall Street Journal— all show fewer people identifying themselves as Republicans. Polls by the sixth, Time, are the only ones to show any gains in Republican identification, but even here the Democratic gains are greater.

Although Republicans obviously are losing ground to Democrats and independents, traditional face-to-face and phone surveys make it difficult to analyze changes among the same set of respondents. Therefore we utilized a web survey panel from YouGov/Polimetrix to find out who had left the party and why. This panel comprised 4,902 respondents who were interviewed both in 2004 and in 2008, giving us party identification at both times and positions on a number of issues in 2008. We also collected demographic information about the respondents.

First, we examined the relationship between change in party identification and demographic characterization. The variable showing change in party identification ranges from minus 6 (strong Republican to strong Democrat) to plus 6 (strong Democrat to strong Republican). Changes within this range were scored accordingly; for example, moving from independent to “leaning Democratic” would be minus 1. We looked at changes in party identification alongside respondents’ race, sex, age, and education level to detect patterns. Across all four of those characteristics there was a swing toward the Democratic Party.

The dominant pattern was that women and younger people moved toward the Democrats more than men and older people did. Women were about twice as likely as men to move Democratic (minus 0.19 for women versus minus 0.10 for men); respondents under thirty moved even more strongly Democratic (minus 0.22). People with a high school education or less were least likely to move Democratic (minus 0.07); postgraduates, at minus 0.22, were most likely to move Democratic. The most surprising finding is that in our sample of about five thousand people, every demographic characteristic we examined had, on average, shifted Democratic— with women, youth, and the highly educated leading the way.

We also examined self-labeled ideology. We expected the movement to be consistent with the respondents’ orientation: liberals would be most likely to move Democratic and conservatives least. Generally this was true, but the surprise was that again, on average, all but one of the self-identified ideological categories showed a shift to the Democrats. Only those calling themselves very conservative showed no significant movement toward the Democrats; for those individuals, the average movement was not statistically different from zero.

WHY DID THEY QUIT THE PARTY?

So far, we have dealt with shifts among the entire sample of respondents. The movement from leaning Democrat to weak or strong Democrat, or from strong Republican to weak Republican, is less interesting than that of respondents who began as Republicans and changed party, becoming either independents or Democrats. In this section we examine what happened to those respondents who were pure independents or Republicans (leaning, weak, or strong) in 2004.

As expected, respondents who considered themselves strong Republicans in 2004 were less likely to move far enough to classify as an independent or Democrat than were those who were leaning or weak Republicans in 2004. Weak Republicans were more likely than strong Republicans to become either independents or Democrats, and those leaning Republican were likelier still.

Overall, however, the shift from Republican identity was mainly to independent. Of all the survey respondents who had become Democrats by 2008, most had been independents in 2004.

What caused respondents to switch their party identification from Republican or independent in 2004 to independent or Democrat in 2008? An obvious possibility is President Bush’s unpopularity: that is, the greater the dislike of Bush, the greater the likelihood of changing party. Of respondents who were Republican in 2004 and 2008, 77.9 percent approved of him in 2008; of those who moved from Republican to independent, only 24.9 percent approved of Bush; the corresponding figure for Republicans and independents who became Democrats was 11.6 percent. Clearly, Bush was responsible for much of the decline in Republican Party membership.

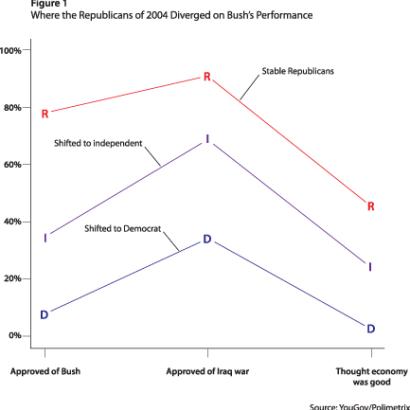

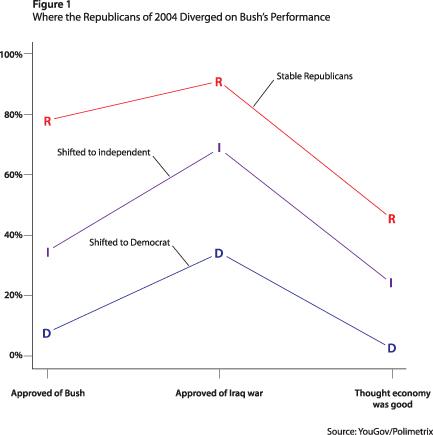

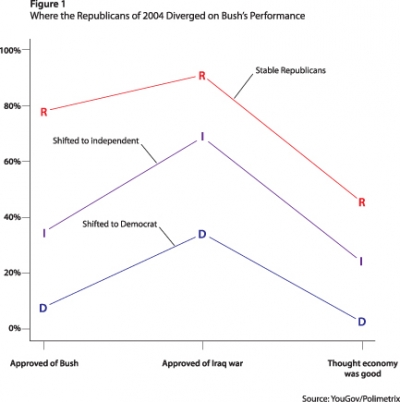

We also analyzed respondents’ evaluations of two issues associated with the Bush administration: the state of the national economy and the war in Iraq. Those remaining Republican favored staying in Iraq (91 percent), and 45.6 percent thought the economy was good. The same figures for those becoming independent were 59.2 favoring another year in Iraq and 24.1 percent saying the economy was good. Consistent with the evaluation of Bush was the result that the Republicans or independents in 2004 who had become Democrats by 2008 were least likely to want to stay in Iraq (34.5 percent) and to think the economy was good (2.8 percent). Figure 1 shows the results of these retrospective evaluations. The opinions of respondents who were stable Republicans from 2004 to 2008 are noted by a red R in each category; the views of those who moved from Republicans to independent are noted by a purple I for each issue; and a blue D is used for the opinions of respondents who moved from either Republican or independent to Democratic.

In sum, those Republicans of 2004 who most disliked President Bush and held the most unfavorable views about the economy and the Iraq war were most likely to leave the Republican Party.

DRIVEN APART BY THE ISSUES

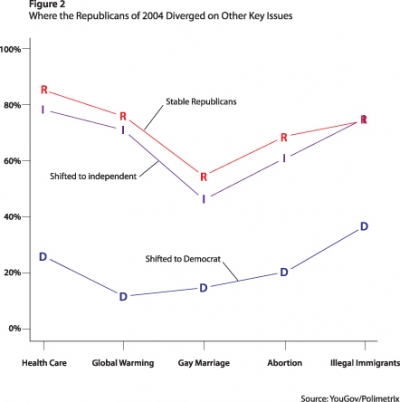

Dislike of President Bush and his policies was one driving force behind the movement toward independent or Democratic affiliation. It is also possible that some Republicans moved to the Democrats because they favored Democratic positions on issues not specifically related to President Bush. To test this hypothesis, we selected a set of issues where party differences are apparent: universal health care, worries over global warming, same-sex marriage, access to abortion, and illegal immigration. The Republican position was stipulated as follows: opposed to universal health care, unconvinced that effects of global warming have begun, opposed to any legal recognition of same-sex couples, opposed to abortion except in case of rape or incest, and in favor of deporting illegal immigrants. Figure 2 plots the percentage hewing to the dominant Republican response for each of the three categories of respondents: stable Republicans (R), Republicans who moved to independent (I), and Republicans or independents who moved to the Democrats (D).

The results consistently show that those who remain Republican are the most likely to favor the Republican position on these issues. The opinions of Republicans who moved to independent, however, remain close to the opinions of stable Republicans. Those who left the Republican Party to become independents were only slightly more likely than stable Republicans to favor universal health care, gay marriage, or abortion rights and to maintain that global warming effects were already present; the two groups actually agreed about deporting illegal immigrants. Meantime, the views of respondents who now identify as Democrats diverged greatly: they were 40 to 60 points different from those of stable Republicans.

Thus, a significant number of Republicans moved toward the Democratic Party thanks to a combination of dislike for President Bush and his policies and a view that the government should do more to guarantee health care, combat global warming, ensure rights for same-sex couples, maintain or strengthen abortion rights, and not deport illegal immigrants.

How did this movement affect the 2008 presidential race? Given the strength and importance of party identification in predicting voting behavior, those who became independents were more likely to support candidate Barack Obama than those who stayed Republican. Our results confirmed this: 87.4 percent of those who remained Republican indicated they would vote for McCain; among those who moved to independent, only 55.1 percent intended to do so. Those who became Democrats during 2004–8 were least likely to vote for McCain, with only 18.8 percent indicating that they would support the Republican candidate.

THE GOP IN THE POST–BUSH ERA

What are the implications for the Republican Party? Naturally, the impact of the Bush presidency will fade: the party will never again have George W. Bush even implicitly on the ticket, and thus future Republican candidates cannot be painted as Bush III, as McCain was. The next Republican presidential candidate will run against President Obama and whatever he has done.

That candidate may, however, be running from a smaller base, as the party has shrunk. In 2004, Bush won re-election by turning out that base and because the war on terrorism was a winning issue for him. With a smaller base, a future Republican candidate will succeed only after successfully appealing to independents and moderates. This could be difficult. In the 2008 general election, moderate Republicans tended to lose to Democrats. Thus the face of the party—the senators and representatives still in office—has become more conservative rather than less and clearly more conservative than the November electorate.

Republicans can either rethink what conservatism means in the twentyfirst century or hope that Obama’s policies drive voters back to them, as during the 1994 congressional elections. Rethinking conservatism will not be easy, given intraparty differences. Social conservatives, for example, oppose abortion and gay marriage, whereas libertarians are pro-choice and often favor same-sex marriage. Republican disagreements over supply-side economics, “compassionate conservatism,” and the overall role of government in education, the environment, and financial regulation also guarantee a rough road ahead.

It is possible that the Obama policies will either cause or be associated with economic recovery, and, in an echo of the Reagan era that began in 1980, lead to a twenty- or twenty-five-year period of Democratic dominance. Only if the 2008 shift to the Democrats were to intensify and become entrenched over the next four years would this shift be plausible. Voters’ allegiance to the Democratic Party could increase, decrease, or even disappear, depending on Obama’s actions, the Republican message, and other events still unforeseen. The next two years could lead to major changes in the American political landscape, and we will continue to track those changes.